Chapter 1 Cigarettes and High Heels 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Correlations Between Creativity In

1 ARTISTIC SCIENTISTS AND SCIENTIFIC ARTISTS: THE LINK BETWEEN POLYMATHY AND CREATIVITY ROBERT AND MICHELE ROOT-BERNSTEIN, 517-336-8444; [email protected] [Near final draft for Root-Bernstein, Robert and Root-Bernstein, Michele. (2004). “Artistic Scientists and Scientific Artists: The Link Between Polymathy and Creativity,” in Robert Sternberg, Elena Grigorenko and Jerome Singer, (Eds.). Creativity: From Potential to Realization (Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004), pp. 127-151.] The literature comparing artistic and scientific creativity is sparse, perhaps because it is assumed that the arts and sciences are so different as to attract different types of minds who work in very different ways. As C. P. Snow wrote in his famous essay, The Two Cultures, artists and intellectuals stand at one pole and scientists at the other: “Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension -- sometimes ... hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding... Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can't find much common ground." (Snow, 1964, 4) Our purpose here is to argue that Snow's oft-repeated opinion has little substantive basis. Without denying that the products of the arts and sciences are different in both aspect and purpose, we nonetheless find that the processes used by artists and scientists to forge innovations are extremely similar. In fact, an unexpected proportion of scientists are amateur and sometimes even professional artists, and vice versa. Contrary to Snow’s two-cultures thesis, the arts and sciences are part of one, common creative culture largely composed of polymathic individuals. -

Survey of Semiotics Textbooks and Primers in the World

A hundred introductionsSign to semiotics, Systems Studies for a million 43(2/3), students 2015, 281–346 281 A hundred introductions to semiotics, for a million students: Survey of semiotics textbooks and primers in the world Kalevi Kull, Olga Bogdanova, Remo Gramigna, Ott Heinapuu, Eva Lepik, Kati Lindström, Riin Magnus, Rauno Thomas Moss, Maarja Ojamaa, Tanel Pern, Priit Põhjala, Katre Pärn, Kristi Raudmäe, Tiit Remm, Silvi Salupere, Ene-Reet Soovik, Renata Sõukand, Morten Tønnessen, Katre Väli Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, 51014 Tartu, Estonia1 Kalevi Kull et al. Abstract. In order to estimate the current situation of teaching materials available in the fi eld of semiotics, we are providing a comparative overview and a worldwide bibliography of introductions and textbooks on general semiotics published within last 50 years, i.e. since the beginning of institutionalization of semiotics. In this category, we have found over 130 original books in 22 languages. Together with the translations of more than 20 of these titles, our bibliography includes publications in 32 languages. Comparing the authors, their theoretical backgrounds and the general frames of the discipline of semiotics in diff erent decades since the 1960s makes it possible to describe a number of predominant tendencies. In the extensive bibliography thus compiled we also include separate lists for existing lexicons and readers of semiotics as additional material not covered in the main discussion. Th e publication frequency of new titles is growing, with a certain depression having occurred in the 1980s. A leading role of French, Russian and Italian works is demonstrated. Keywords: history of semiotics, semiotics of education, literature on semiotics, teaching of semiotics 1 Correspondence should be sent to [email protected]. -

THE PHENOMENON of ABSURDITY in COMIC a Semiotic-Pragmatic Analysis of Tahilalats Comic

THE PHENOMENON OF ABSURDITY IN COMIC A Semiotic-Pragmatic Analysis of Tahilalats Comic Name: Muh. Zakky Al Masykuri Affiliation: Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia Abstract Code: ABS-ICOLLITE-20183 Introduction & Literature Review • Comics as a medium of communication to express attitudes, opinions or ideas. Comics have an extraordinary ability to adapt themselves used for various purposes (McCloud, 1993). • Tahilalats comic has the power to convey information in a popular manner, but it seems absurd to the readers. • Tahilalats comic have many signs which confused the readers, thus encouraging readers to think hard in finding the meaning conveyed. • The absurdity phenomenon portrayed in the Tahilalats comic is related to the philosophical concept of absurdity presented by Camus. • French absurde from Classical Latin absurdus, not to be heard of from ab-, intensive + surdus, dull, deaf, insensible [1]. • Absurd is the state or condition in which human beings exist in an irrational and meaningless universe and in which human life has no ultimate meaning [2]. • Absurd refers to the conflict between humans and their world (Camus, 1999). • Comics is sequential images, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer (McCloud, 1993). 1 YourDictionary. (n.d.). Absurd. In YourDictionary. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.yourdictionary.com/absurd 2 Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Absurd. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/absurd • Everything in human life is seen as a sign and every sign has a meaning (Hoed, 2014). • Semiotics is defined as the study of objects, events, and all cultures as signs (Wahjuwibowo, 2020). -

THE NAKED APE By

THE NAKED APE by Desmond Morris A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd. PRINTING HISTORY Jonathan Cape edition published October 1967 Serialized in THE SUNDAY MIRROR October 1967 Literary Guild edition published April 1969 Transrvorld Publishers edition published May 1969 Bantam edition published January 1969 2nd printing ...... January 1969 3rd printing ...... January 1969 4th printing ...... February 1969 5th printing ...... June1969 6th printing ...... August 1969 7th printing ...... October 1969 8th printing ...... October 1970 All rights reserved. Copyright (C 1967 by Desmond Morris. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mitneograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 30 Bedford Square, London Idi.C.1, England. Bantam Books are published in Canada by Bantam Books of Canada Ltd., registered user of the trademarks con silting of the word Bantam and the portrayal of a bantam. PRINTED IN CANADA Bantam Books of Canada Ltd. 888 DuPont Street, Toronto .9, Ontario CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, 9 ORIGINS, 13 SEX, 45 REARING, 91 EXPLORATION, 113 FIGHTING, 128 FEEDING, 164 COMFORT, 174 ANIMALS, 189 APPENDIX: LITERATURE, 212 BIBLIOGRAPHY, 215 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is intended for a general audience and authorities have therefore not been quoted in the text. To do so would have broken the flow of words and is a practice suitable only for a more technical work. But many brilliantly original papers and books have been referred to during the assembly of this volume and it would be wrong to present it without acknowledging their valuable assistance. At the end of the book I have included a chapter-by-chapter appendix relating the topics discussed to the major authorities concerned. -

Primate Aesthetics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Primate Aesthetics Chelsea L. Sams University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sams, Chelsea L., "Primate Aesthetics" (2016). Masters Theses. 375. https://doi.org/10.7275/8547766 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/375 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2016 Department of Art PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________ Robin Mandel, Chair ___________________________________ Melinda Novak, Member ___________________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member ___________________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION For Christopher. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly indebted to my committee: Robin Mandel, for his patient guidance and for lending me his Tacita Dean book; to Melinda Novak for taking a chance on an artist, and fostering my embedded practice; and to Jenny Vogel for introducing me to the medium of performance lecture. To the longsuffering technicians Mikaël Petraccia, Dan Wessman, and Bob Woo for giving me excellent advice, and tolerating question after question. -

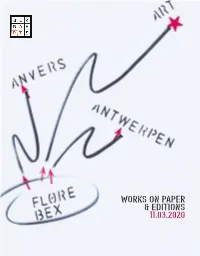

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

Messages, Signs, and Meanings: a Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication (Studies in Linguistic and Cultural Anthropology)

Messages, Signs, and Meanings A Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication 3rdedition Volume 1 in the series Studies in Linguistic and Cultural Anthropology Series Editor: Marcel Danesi, University of Toronto Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. Toronto Disclaimer: Some images and text in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Messages, Signs, and Meanings: A Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication Theory, 3rdEdition by Marcel Danesi First published in 2004 by Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. 180 Bloor Street West, Suite 801 Toronto, Ontario M5S 2V6 www.cspi.org Copyright 0 2004 Marcel Danesi and Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the written permission of Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., except for brief passages quoted for review purposes. In the case of photocopying, a licence may be obtained from Access Copyright: One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M5E 1E5, (416) 868-1620, fax (416) 868- 1621, toll-free 1-800-893-5777, www.accesscopyright.ca. Every reasonable effort has been made to identify copyright holders. CSPI would be pleased to have any errors or omissions brought to its attention. CSPl gratefully acknowledges financial support for our publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Danesi, Marcel, 1946- Messages and meanings : an introduction to semiotics /by Marcel Danesi - [3rd ed.] (Studies in linguistic and cultural anthropology) Previously titled: Messages and meanings : sign, thought and culture. -

Semiotics of Food

Semiotica 2016; 211: 19–26 Simona Stano* Introduction: Semiotics of food DOI 10.1515/sem-2016-0095 From an anthropological point of view, food is certainly a primary need: our organism needs to be nourished in order to survive, grow, move, and develop. Nonetheless, this need is highly structured, and it involves substances, prac- tices, habits, and techniques of preparation and consumption that are part of a system of differences in signification (Barthes 1997 [1961]). Let us consider, for example, the definition of what is edible and what is not. In Cambodia, Vietnam, and many Asian countries people eat larvae, locusts, and other insects. In Peru it is usual to cook hamster and llama’s meat. In Africa and Australia it is not uncommon to eat snakes. By contrast, these same habits would probably seem odd, or at least unfamiliar, to European or North American inhabitants. Human beings eat, first of all, to survive. But in the social sphere, food assumes meanings that transcend its basic function and affect perceptions of edibility (Danesi 2004). Every culture selects, within a wide range of products with nutritional capacity, a more or less large quantity destined to become, for such a culture, “food.” And even though cultural materialism has explained these processes through functionalist and materialis- tic theories conceiving them in terms of beneficial adaptions (Harris 1985; Sahlins 1976), most scholars claim that the transformation of natural nutrients into food cannot be reduced to simple utilitarian rationality or availability logics (cf. Fischler 1980, 1990). In fact, this process is part of a classification system (Douglas 1972), so it should be rather referred to a different type of rationality, which is strictly related to symbolic representations. -

Opposition Theory and the Interconnectedness of Language, Culture, and Cognition

Sign Systems Studies 37(1/2), 2009 Opposition theory and the interconnectedness of language, culture, and cognition Marcel Danesi Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S2, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The theory of opposition has always been viewed as the founding prin- ciple of structuralism within contemporary linguistics and semiotics. As an analy- tical technique, it has remained a staple within these disciplines, where it conti- nues to be used as a means for identifying meaningful cues in the physical form of signs. However, as a theory of conceptual structure it was largely abandoned under the weight of post-structuralism starting in the 1960s — the exception to this counter trend being the work of the Tartu School of semiotics. This essay revisits opposition theory not only as a viable theory for understanding conceptual structure, but also as a powerful technique for establishing the interconnectedness of language, culture, and cognition. Introduction The founding principle of structuralism in semiotics, linguistics, psychology, and anthropology is the theory of opposition. The philo- sophical blueprint of this principle can be traced back to the concept of dualism in the ancient world (Hjelmslev 1939, 1959; Benveniste 1946). It was implicit in Saussure’s (1916) own principle of différence. In the 1930s the Prague School linguists (Trubetzkoy 1936, 1939; Jakobson 1939) and several Gestalt psychologists (especially Ogden 1932) gave the principle its scientific articulation and, in the sub- sequent decades of the 1940s and 1950s, it was used to carry out exten- sive analyses of languages and to establish universal patterns in 12 Marcel Danesi linguistic structure. -

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM Charles Sanders Peirce From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced /ˈpɜrs/ purse[1]) Charles Sanders Peirce (September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Peirce was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. It is largely his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, and semiotics (and his founding of pragmatism) that are appreciated today. In 1934, the philosopher Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers and America's greatest logician".[2] An innovator in many fields (including philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, mathematics, statistics, research methodology, and the design of experiments in astronomy, geophysics, and psychology) Peirce considered himself a logician first and foremost. He made major contributions to logic, but logic for him encompassed much of that which is now called epistemology and philosophy of science. He saw logic as the Charles Sanders Peirce formal branch of semiotics, of which he is a founder. As early as 1886 he saw that logical operations could be carried out by Born September 10, 1839 electrical switching circuits, an idea used decades later to Cambridge, Massachusetts produce digital computers.[3] Died April 19, 1914 (aged 74) Milford, Pennsylvania Contents Nationality American 1 Life Fields Logic, Mathematics, 1.1 United States Coast Survey Statistics, Philosophy, 1.2 Johns Hopkins University Metrology, Chemistry 1.3 Poverty Religious Episcopal but 2 Reception 3 Works stance unconventional 4 Mathematics 4.1 Mathematics of logic C. -

Find Book # on the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain

EDVPNKOYORFZ // Doc > On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain On th e Th irteenth Stroke of Midnigh t: Surrealist Poetry in Britain Filesize: 7.63 MB Reviews A must buy book if you need to adding benefit. We have study and so i am sure that i am going to likely to study once again again in the foreseeable future. I realized this book from my i and dad encouraged this ebook to discover. (Duane Fadel) DISCLAIMER | DMCA ISTVDZEZULX3 « Book ~ On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain ON THE THIRTEENTH STROKE OF MIDNIGHT: SURREALIST POETRY IN BRITAIN Carcanet Press Ltd, United Kingdom, 2013. Undefined. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. This book, the first published anthology of British surrealist poetry, takes its title from Herbert Read s words when he opened the Surrealist Poems and Objects exhibition at the London Gallery at midnight on 24 November 1937. Within a few years the Second World War would eectively fragment the British surrealist movement, dispersing its key members and leaving the surrealist flame flickering only in isolated moments and places. Yet British surrealist writing was vibrant and, at its best, durable, and now takes its place in the wider European context of literary surrealism. On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight includes work by Emmy Bridgwater, Jacques B. Brunius, Ithell Colquhoun, Hugh Sykes Davies, Toni del Renzio, Anthony Earnshaw, David Gascoyne, Humphrey Jennings, Sheila Legge, Len Lye, Conroy Maddox, Reuben Medniko, George Melly, E.L.T. Mesens, Desmond Morris, Grace Pailthorpe, Roland Penrose, Edith Rimmington, Roger Roughton, Simon Watson Taylor and John W.