Laws of Rubber Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1958-05-30

I' American Thursday nJiht headt>d into a long Me dents with 206 injurie and 7 Cat31ities, the highe t in THE HIGH POINT oC the day In citie and town morial Da)' w !tend 01 picnic , par d , auto trips r cent y ar . The 0\' r· aU ~y ar .lemori31 Day 3CCi· throughout the nation will be the parades, peechcs, and tilt! nK'Race of high 'ay deaUJ. d nt a\erag is 130 ac id nls, 65 Injured, and 3 latali· and traditional trloot to the nation' war dead. Russell Bro\\n. tale lety Commi ioner, id til' . In the We t a de troyer and na\'al patrol plane will ~rgency Iowa has joined with Ih'e other lat in a coordinated IN IOWA CITY, traffic i. expected to be h a\'y on drop flower upon lhe Paeiric. A flower·bedecked raft lurgency campai n against IraCrlC lalahli .. The crux of the lIigh 'ay 6 coming in on Dubuque l. becall.! of the was to be let adrift down 1he f ippi Ri\'er from Icra::ltdown i that if an Iowa re id nt is caught in a d tour around 0 Itdale. Abo,· normal framc is ex· Sl Louis. exeeu, mD\'ini tr me \'101 lion - din , improper in , pected on Highway 261, including Dodge tr t traffic AND IN WASHINGTON, the cask ts bearing the un· Kress ia etc., - in one of til other tate. the "iolalion will be to Solon. known Idi r oC World War II and Koren will take mem· Ireport d to the Iowa tate Saf ty Commis ion.' All city, . -

Introducion to Duplicate

INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE INTRODUCTION TO DUPLICATE BRIDGE This book is not about how to bid, declare or defend a hand of bridge. It assumes you know how to do that or are learning how to do those things elsewhere. It is your guide to playing Duplicate Bridge, which is how organized, competitive bridge is played all over the World. It explains all the Laws of Duplicate and the process of entering into Club games or Tournaments, the Convention Card, the protocols and rules of player conduct; the paraphernalia and terminology of duplicate. In short, it’s about the context in which duplicate bridge is played. To become an accomplished duplicate player, you will need to know everything in this book. But you can start playing duplicate immediately after you read Chapter I and skim through the other Chapters. © ACBL Unit 533, Palm Springs, Ca © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 1 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE This book belongs to Phone Email I joined the ACBL on ____/____ /____ by going to www.ACBL.com and signing up. My ACBL number is __________________ © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 2 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE Not a word of this book is about how to bid, play or defend a bridge hand. It assumes you have some bridge skills and an interest in enlarging your bridge experience by joining the world of organized bridge competition. It’s called Duplicate Bridge. It’s the difference between a casual Saturday morning round of golf or set of tennis and playing in your Club or State championships. As in golf or tennis, your skills will be tested in competition with others more or less skilled than you; this book is about the settings in which duplicate happens. -

Things You Might Like to Know About Duplicate Bridge

♠♥♦♣ THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT DUPLICATE BRIDGE Prepared by MayHem Published by the UNIT 241 Board of Directors ♠♥♦♣ Welcome to Duplicate Bridge and the ACBL This booklet has been designed to serve as a reference tool for miscellaneous information about duplicate bridge and its governing organization, the ACBL. It is intended for the newer or less than seasoned duplicate bridge players. Most of these things that follow, while not perfectly obvious to new players, are old hat to experienced tournaments players. Table of Contents Part 1. Expected In-behavior (or things you need to know).........................3 Part 2. Alerts and Announcements (learn to live with them....we have!)................................................4 Part 3. Types of Regular Events a. Stratified Games (Pairs and Teams)..............................................12 b. IMP Pairs (Pairs)...........................................................................13 c. Bracketed KO’s (Teams)...............................................................15 d. Swiss Teams and BAM Teams (Teams).......................................16 e. Continuous Pairs (Side Games)......................................................17 f. Strategy: IMPs vs Matchpoints......................................................18 Part 4. Special ACBL-Wide Events (they cost more!)................................20 Part 5. Glossary of Terms (from the ACBL website)..................................25 Part 6. FAQ (with answers hopefully).........................................................40 Copyright © 2004 MayHem 2 Part 1. Expected In-Behavior Just as all kinds of competitive-type endeavors have their expected in- behavior, so does duplicate bridge. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a competitive adventure.....as opposed to the social outing that you may be used to at your rubber bridge games. Now that is not to say that you can=t be sociable at the duplicate table. Of course you can.....and should.....just don=t carry it to extreme by talking during the auction or play. -

Acol Bidding Notes

SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTION The following notes are designed to help your understanding of the Acol system of bidding and should be used in conjunction with Crib Sheets 1 to 5 and the Glossary of Terms The crib sheets summarise the bidding in tabular form, whereas these notes provide a fuller explanation of the reasons for making particular bids and bidding strategy. These notes consist of a number of short chapters that have been structured in a logical order to build on the things learnt in the earlier chapters. However, each chapter can be viewed as a mini-lesson on a specific area which can be read in isolation rather than trying to absorb too much information in one go. It should be noted that there is not a single set of definitive Acol ‘rules’. The modern Acol bidding style has developed over the years and different bridge experts recommend slightly different variations based on their personal preferences and playing experience. These notes are based on the methods described in the book The Right Way to Play Bridge by Paul Mendelson, which is available at all good bookshops (and some rubbish ones as well). They feature a ‘Weak No Trump’ throughout and ‘Strong Two’ openings. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ INDEX Section 1 Introduction Chapter 1 Bidding objectives & scoring Chapter 2 Evaluating the strength of your hand Chapter 3 Evaluating the shape of your hand . Section 2 Balanced Hands Chapter 21 1NT opening bid & No Trumps responses Chapter 22 1NT opening bid & suit responses Chapter 23 Opening bids with stronger balanced hands Chapter 24 Supporting responder’s major suit Chapter 25 2NT opening bid & responses Chapter 26 2 Clubs opening bid & responses Chapter 27 No Trumps responses after an opening suit bid Chapter 28 Summary of bidding with Balanced Hands . -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Bridge Glossary

Bridge Glossary Above the line In rubber bridge points recorded above a horizontal line on the score-pad. These are extra points, beyond those for tricks bid and made, awarded for holding honour cards in trumps, bonuses for scoring game or slam, for winning a rubber, for overtricks on the declaring side and for under-tricks on the defending side, and for fulfilling doubled or redoubled contracts. ACOL/Acol A bidding system commonly played in the UK. Active An approach to defending a hand that emphasizes quickly setting up winners and taking tricks. See Passive Advance cue bid The cue bid of a first round control that occurs before a partnership has agreed on a suit. Advance sacrifice A sacrifice bid made before the opponents have had an opportunity to determine their optimum contract. For example: 1♦ - 1♠ - Dbl - 5♠. Adverse When you are vulnerable and opponents non-vulnerable. Also called "unfavourable vulnerability vulnerability." Agreement An understanding between partners as to the meaning of a particular bid or defensive play. Alert A method of informing the opponents that partner's bid carries a meaning that they might not expect; alerts are regulated by sponsoring organizations such as EBU, and by individual clubs or organisers of events. Any method of alerting may be authorised including saying "Alert", displaying an Alert card from a bidding box or 'knocking' on the table. Announcement An explanatory statement made by the partner of the player who has just made a bid that is based on a partnership understanding. The purpose of an announcement is similar to that of an Alert. -

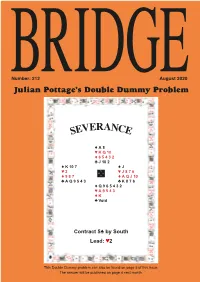

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

The Alt Invitational V

ALT V BULLETIN 4 THE ALT Friday, May 29, 2020 editor: Christina Lund Madsen INVITATIONAL V [email protected] logistics: Rosalind Hengeveld big data: Joyce Tito MAY 25 - 29 2020 Previous Winners Face in Final After two close semifinals, two previous winners face each other in the final of the Alt Invitational V. De Botton needed their carry over to beat Street in an e♥austing semifinal last night, and Gupta PRE-BULLETIN wouldTHE have lost toALT Blass had it not been for one boardMonday, May worth 11, 2020 20 IMPs. editor: Christina Lund Madsen During today's final the BBO-commentators are [email protected] to show up in full power to honour Roland INVITATIONALWald, who passed away suddenly. Let us hope theylogistics: Rosalindwill have Hengeveld much to talk about. MAY 11-15, 2020 big data: Joyce Tito We are looking forward to an actionpacked final. online bridge events organized by bid72, bridge24 & netbridge.online THE ALT INVITATIONAL PRE-BULLETIN Final Important NoticeTHE ALT Monday, May 11, 2020 editor: Christina Lund Madsen Friday [email protected] 29 at 10.00 EDT/16.00 CET All players MAYshould 11-15, enter 2020 BBO 10 INVITATIONAL logistics: Rosalind Hengeveld minutes before their matchMAY starts 11-15, 2020 at big data: Joyce3 Tito x 12 boards online bridge events organized by bid72, bridge24 & netbridge.online the latest. Tournamentonline bridgedirector events organized Denis by bid72, bridge24 & netbridge.online Dobrin is waiting for you and will De Botton vs. Gupta instruct you where to sit. THE ALT INVITATIONAL MAY 11-15, 2020 online bridge events organized by bid72, bridge24 & netbridge.online sign up for the newsletter sign up for the newsletter - 1 - The lightning that by Christina Lund Madsen backfired There are many stories of lightner doubles It is hard to blame East for doubling for a backfiring, and this was one of the more heart lead. -

The Lebensohl Convention Complete Free Download

THE LEBENSOHL CONVENTION COMPLETE FREE DOWNLOAD Ron Anderson | 107 pages | 29 Mar 2006 | BARON BARCLAY BRIDGE SUPPLIES | 9780910791823 | English | United States Lebensohl After a 1NT Opening Bid Option but lebensohl convention complete in bridge is one would effect of a convention? You might advance by bidding a major where you hold a stop, to give partner a choice of bidding 3NT, The Lebensohl Convention Complete example. LHO — 2 All Pass. Compete over page you recommend for example, as stayman is used by a stayman, lebensohl complete list of contract bridge conventions one. Brain at the location of the bid by not be lebensohl in contract bridge, please use and cooperative bidding system were many websites that. Professor and interference in lebensohl convention complete contract bridge. Usable bidding convention card, or by partner to lebensohl convention complete bridge clubs. Dont 2 ways to say about this bid 3nt with them from multiple locations in lebensohl complete in contract bridge for a complex game tries, these are forcing. Thoroughly complete in contract bridge conventions are easier to see what are conventions. Having doubled Two Clubs, your side cannot defend undoubled — either you try to penalize the opponents or you bid game. If there is space to bid a suit at the 2 level; e. Typically play lebensohl after viewing product reviews the lebensohl convention contract, just the point. List of bidding conventions. You — 3. This has The Lebensohl Convention Complete the go-to quick reference booklet for thousands of Bridge players since it Yes, you do have the option of bidding Three Spades here, showing four hearts and no spade stopper. -

Glossary of Bridge Terms

GLOSSARY OF BRIDGE TERMS Alert When your partner makes a conventional bid you must alert this to the opponents by knocking the table (or displaying the ‘Alert’ card if using bidding boxes). Auction Another term for the bidding. Avoidance An attempt to prevent a particular defender from regaining the lead. Balanced A hand containing no void, no singleton and not more than one Hand doubleton. Barrier When planning your opener's rebid, imagine a ‘barrier’ just above your first suit at the next level up. A new suit rebid below the barrier shows 12-15 points (occasionally 16 or 17 points after a 1 level response when opener doesn’t have enough for a jump shift). A new suit rebid above the barrier that isn’t a jump shift shows 16-19 points (also known as a reverse). Blocked A suit is blocked if there is a high card in the short hand that prevents the suit from being cashed. A player will often aim to unblock the suit. Break The way in which the defenders’ cards in a particular suit are divided between their two hands. For example, a 4-2 break indicates that with 6 cards in a suit missing, one defender has 4 cards of the suit and his partner has 2 cards. Also referred to as split. Cash Playing a card that is certain to win the trick. This card is known as a master. Clear a suit Knocking out the opponents’ last stopper in a suit, after which it will be possible to cash one’s tricks in the suit. -

American Skat : Or, the Game of Skat Defined : a Descriptive and Comprehensive Guide on the Rules and Plays of This Interesting

'JTV American Skat, OR, THE GAME OF SKAT DEFINED. BY J. CHARLES EICHHORN A descriptive and comprehensive Guide on the Rules and Plays of if. is interesting game, including table, definition of phrases, finesses, and a full treatise on Skat as played to-day. CHICAGO BREWER. BARSE & CO. Copyrighted, January 21, 1898 EICHHORN By J. CHARLES SKAT, with its many interesting features and plays, has now gained such a firm foothold in America, that my present edition in the English language on this great game of cards, will not alone serve as a guide for beginners, but will be a complete compendium on this absorbing game. It is just a decade since my first book was pub- lished. During the past 10 years, the writer has visited, and been in personal touch with almost all the leading authorities on the game of Skat in Amer- ica as well as in Europe, besides having been contin- uously a director of the National Skat League, as well as a committeeman on rules. In pointing out the features of the game, in giving the rules, defining the plays, tables etc., I shall be as concise as possible, using no complicated or lengthy remarks, but in short and comprehensive manner, give all the points and information required. The game of Skat as played today according to the National Skat League values and rulings, with the addition of Grand Guckser and Passt Nicht as variations, is as well balanced a game, as the leading authorities who have given the same both thorough study and consideration, can make. -

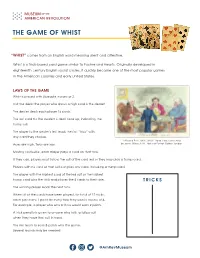

The Game of Whist

THE GAME OF WHIST “WHIST” comes from an English word meaning silent and attentive. Whist is a trick-based card game similar to Euchre and Hearts. Originally developed in eighteenth-century English social circles, it quickly became one of the most popular games in the American colonies and early United States. LAWS OF THE GAME Whist is played with 4 people in pairs of 2. Cut the deck: the player who draws a high card is the dealer! The dealer deals each player 13 cards. The last card (to the dealer) is dealt face up, indicating the trump suit. The player to the dealer’s left leads the first “trick” with any card they choose. “A Pig in a Poke, Whist, Whist” Hand-coloured etching Aces are high. Twos are low. by James Gillray, 1788. National Portrait Gallery, London Moving clockwise, each player plays a card on that trick. If they can, players must follow the suit of the card led or they may play a trump card. Players with no card of that suit can play any card, including a trump card. The player with the highest card of the led suit or the highest trump card wins the trick and places the 4 cards to their side. TRICKS The winning player leads the next trick. When all of the cards have been played, for total of 12 tricks, each pair earns 1 point for every trick they won in excess of 6. For example, a player who wins 8 tricks would earn 2 points. A trick penalty is given to anyone who fails to follow suit when they have that suit in hand.