The Fellowship Inn Project Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LYDERIS! Londone

NAUJIENOS SAVIEMS 2019 M. birželio 20–liepos 10 D. NR. 503 www.tiesa.com WWW.LITKRAFT.CO.UK 24/7 TEL. 0208 635 5555 FREE LEADING LITHUANIAN NEWSPAPER IN THE UK Joninės LYDERIS! Londone. Kodėl gi ne? Trumpiausia metų naktis nuo seno sureikšminama, mistifikuojama. Lietuviai manė, kad ji stebuklinga, per ją galima išsipranašauti ateitį, laimę, asmeninio gyvenimo gerovę ir tąnakt švęsdavo Rasų šventę. Vėliau, atėjus krikščionybei, ši šventė susieta su Šv. Jono Krikštytojo gimimo diena ir pradėta vadinti Joninėmis, bet šimtmečių tradicijos ir mistiniai papročiai pamiršti nebuvo. Ar įmanoma pagal senovinius papročius atšvęsti Jonines JK ar jos sostinėje? Žinoma! 8 Edvardo Blaževič nuotr. JK PER SAVAITĘ 2 „TIESOS“ INTERVIU 4 LIETUVA 6 SPORTAS 7 RENGINIAI 9 ĮVAIRENYBĖS 11 SKELBIMAI 12 2 2019 M. BIRŽELIO 20–LIEPOS 10 D. Nr. 503 JK PER SAVaitę www.facebook.com/tiesa.news/ Bandymas pasiteisino, plastiko „Morrisons“ nebeliks dymų trijose „Morrisons“ parduotuvė- se. Per šį laiką nupirktų palaidų vaisių ir daržovių kiekis padidėjo vidutiniškai 40 proc. Tikimasi, kad bandomosiose par- duotuvėse įdiegtas sprendimas pa ska‑ tins perėjimą prie apsipirkimo be mai- šelių ir kitose tinklo parduotuvėse. Iš viso šiemet planuojama palaidų vaisių ir daržovių skyrius įrengti dar 60‑yje „Morrisons“ siūlo ateiti pirkti „Morrisons“ parduotuvių, vėliau šie vaisių ir daržovių su savo maišeliais. skyriai bus įrengiami atnaujinant par- „Flickr“ nuotr. duotuves visoje JK. Skaičiuojama, kad taip per savaitę JungTinės KARALysTės maž- būtų sutaupoma apie 3 tonas plastiko, meninės prekybos gigantas „Morrisons“ arba 156 tonas per metus. Princas klausė M. Gražinytės-Tylos diriguojamos G. Mahlerio Antrosios simfonijos. planuoja tapti pirmuoju Didžiosios Bri- Drew Kirkas, už vaisius ir daržoves tanijos prekybos centru, draudžiančiu atsakingo „Morrisons“ padalinio vado- plastikines pakuotes vaisiams ir daržo- vas, sakė: „Daugelis mūsų klientų norė- Baltijos kelio 30‑mečiui skirtą vėms, rašo Eveningtimes.co.uk. -

2017-18 Annual Review

Historic Royal Places – Spines Format A4 Portrait Spine Width 35mm Spine Height 297mm HRP Text 20pt (Tracked at +40) Palace Text 30pt (Tracked at -10) Icon 20mm Wide (0.5pt/0.25pt) Annual Review 2017/18 2 Contents 06 Welcome to another chapter in our story 07 Our work is guided by four principles 08 Chairman and Chief Executive: Introduction and reflection 10 Guardianship 16 Showmanship 24 Discovery 32 A Royal Year 36 Independence 42 Money matters 43 Visitor trends 44 Summarised financial statements 46 Trustees and Directors 48 Supporters 50 Acknowledgments Clockwise from top left: The White Tower, Tower of London; the West Front, Hampton Court Palace; the East Front, Kensington Palace; the South Front, Hillsborough Castle; Kew Palace; Banqueting House. 4 • It has been a record-breaking 12 months with more than Guardianship: visits to our sites, membership topping 101,000 Welcome to 4.7 million Our work is We exist for tomorrow, not just for yesterday. Our job is to give and our commercial teams exceeding their targets. another guided by four these palaces a future as valuable as their past. We know how • It was our busiest ever year at Kensington Palace as visitors precious they and their contents are, and we aim to conserve chapter in flocked to see our exhibitions of Princess Diana’s dresses and principles them to the standard they deserve: the best. 'Enlightened Princesses', and a new display of diamond and our story emerald jewellery. At Hampton Court, we came close to Discovery: reaching a million visitors for the first time. -

Annual Report 2017−2018

ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT REPORT COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL ROYAL 2017−2018 www.royalcollection.org.uk ANNUAL REPORT 2017−2018 ROYA L COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2018 www.royalcollection.org.uk AIMS OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST In fulfilling The Trust’s objectives, the Trustees’ aims are to ensure that: ~ the Royal Collection (being the works of art ~ the Royal Collection is presented and held by The Queen in right of the Crown interpreted so as to enhance public and held in trust for her successors and for the appreciation and understanding; nation) is subject to proper custodial control and that the works of art remain available ~ access to the Royal Collection is broadened to future generations; and increased (subject to capacity constraints) to ensure that as many people as possible are ~ the Royal Collection is maintained and able to view the Collection; conserved to the highest possible standards and that visitors can view the Collection ~ appropriate acquisitions are made when in the best possible condition; resources become available, to enhance the Collection and displays of exhibits ~ as much of the Royal Collection as possible for the public. can be seen by members of the public; When reviewing future plans, the Trustees ensure that these aims continue to be met and are in line with the Charity Commission’s general guidance on public benefit. This Report looks at the achievements of the previous 12 months and considers the success of each key activity and how it has helped enhance the benefit to the nation. -

Beer Festival News 30 Supervised, Within Limited Hours, Rather Pricing Alone Will Not Help Pubs at All

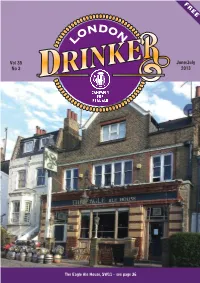

F R E E Vol 35 June/July No 3 2013 The Eagle Ale House, SW11 – see page 36 23-25 NEW END • HAMPSTEAD VILLAGE • NW3 1JD Best Tel: 020 7794 0258 London Pub of the Year 2011 twitter: @dukeofhamilton Fancy a Pint Reviewers www.thedukeofhamilton.com Awards All ales £2.70 a pint Mondays and Tuesdays. See website for ales on tap. Editorial alcohol consumption and seeking measures London Drinker is published on behalf of the to reduce it. London Branches of CAMRA, the • We oppose the mass media advertising of Campaign for Real Ale Limited, alcoholic drinks that inevitably appeals to and edited by Tony Hedger. younger people who are more susceptible Material for publication should preferably be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. to ‘branding’ rather than to discerning Correspondents unable to send letters to the drinkers who are more likely to dismiss it editors electronically may post them to AMRA held its AGM and Members’ as a marketing ploy that simply increases Brian Sheridan at 4, Arundel House, Heathfield CConference in Norwich over the 20/21 the prices they have to pay. Road, Croydon CR0 1EZ. April weekend. London Drinker is intended So where do we now stand on minimum for all real ale drinkers and pub-goers and Press releases should be sent by email to pricing? An article in the Morning [email protected] we do not as a rule cover internal CAMRA Advertiser has misleadingly suggested that Changes to pubs or beers should be reported to matters. However, what comes out of the Capital Pubcheck, annual conference is very much what makes we have been forced into a U-turn but, in 2 Sandtoft Road, London SE7 7LR or by CAMRA the organisation it is – for better, for quoting the speech made by Peter Alexander e-mail to [email protected]. -

Regulated Child Care Programs in Senate District 1, Lawrence M

Regulated Child Care Programs in Senate District 1, Lawrence M. Farnese (D) Total Regulated Child Care Programs: 174 Total Pre‐K Counts: 2 Total Head Start Supplemental: 5 Star 4: 13 Star 3: 19 Star 2: 13 Star 1: 114 No Star Level: 8 Keystone Star Head Start Program Name Address City Zip Level Pre‐K Counts Supplemental Bright Horizons Child Care and Learning Center 401 N 21ST ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4‐ Acc No No CHILDRENS VILLAGE INC 125 N 8TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19106 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes COM COLLEGE OF PHILA CHILD DEV CENTER 540 N 16TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4‐ Acc No No JEFFERSON CHILD CARE CENTER 912 WALNUT ST # 28 PHILADELPHIA 19107 STAR 4‐ Acc No No NORRIS SQUARE CHILDRENS CENTER 2011 N MASCHER ST PHILADELPHIA 19122 STAR 4‐ Acc No No SETTLEMENT MUSIC SCHOOL 416 QUEEN ST PHILADELPHIA 19147 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes WESTERN COMMUNITY CENTER 1613 SOUTH ST # 21 PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes ARCH STREET PRESCHOOL 1724 ARCH ST PHILADELPHIA 19103 STAR 4 No No BEE NEES BABIES EDUCATIONAL LRNG CTR 803 N 15TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4 No No CANAAN LAND FAMILY CHILD CARE 1007 S 18TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4 No No CHINATOWN LEARNING CENTER 1034 SPRING ST PHILADELPHIA 19107 STAR 4 No Yes COOKIES DAY CARE CENTER 2135 S 17TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19145 STAR 4 No No EARLY CHILDHOOD ENVIRONMENTS LLC 762 S BROAD ST PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4 No No FRANKLIN DAY NURSERY 719 JACKSON ST PHILADELPHIA 19148 STAR 4 No No KEN‐CREST SERVICES‐SOUTH CENTER 504 MORRIS ST PHILADELPHIA 19148 STAR 4 No No KINDERCARE LEARNING CENTER 303009 1700 MARKET ST PHILADELPHIA -

"G" S Circle 243 Elrod Dr Goose Creek Sc 29445 $5.34

Unclaimed/Abandoned Property FullName Address City State Zip Amount "G" S CIRCLE 243 ELROD DR GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $5.34 & D BC C/O MICHAEL A DEHLENDORF 2300 COMMONWEALTH PARK N COLUMBUS OH 43209 $94.95 & D CUMMINGS 4245 MW 1020 FOXCROFT RD GRAND ISLAND NY 14072 $19.54 & F BARNETT PO BOX 838 ANDERSON SC 29622 $44.16 & H COLEMAN PO BOX 185 PAMPLICO SC 29583 $1.77 & H FARM 827 SAVANNAH HWY CHARLESTON SC 29407 $158.85 & H HATCHER PO BOX 35 JOHNS ISLAND SC 29457 $5.25 & MCMILLAN MIDDLETON C/O MIDDLETON/MCMILLAN 227 W TRADE ST STE 2250 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 $123.69 & S COLLINS RT 8 BOX 178 SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $59.17 & S RAST RT 1 BOX 441 99999 $9.07 127 BLUE HERON POND LP 28 ANACAPA ST STE B SANTA BARBARA CA 93101 $3.08 176 JUNKYARD 1514 STATE RD SUMMERVILLE SC 29483 $8.21 263 RECORDS INC 2680 TILLMAN ST N CHARLESTON SC 29405 $1.75 3 E COMPANY INC PO BOX 1148 GOOSE CREEK SC 29445 $91.73 A & M BROKERAGE 214 CAMPBELL RD RIDGEVILLE SC 29472 $6.59 A B ALEXANDER JR 46 LAKE FOREST DR SPARTANBURG SC 29302 $36.46 A B SOLOMON 1 POSTON RD CHARLESTON SC 29407 $43.38 A C CARSON 55 SURFSONG RD JOHNS ISLAND SC 29455 $96.12 A C CHANDLER 256 CANNON TRAIL RD LEXINGTON SC 29073 $76.19 A C DEHAY RT 1 BOX 13 99999 $0.02 A C FLOOD C/O NORMA F HANCOCK 1604 BOONE HALL DR CHARLESTON SC 29407 $85.63 A C THOMPSON PO BOX 47 NEW YORK NY 10047 $47.55 A D WARNER ACCOUNT FOR 437 GOLFSHORE 26 E RIDGEWAY DR CENTERVILLE OH 45459 $43.35 A E JOHNSON PO BOX 1234 % BECI MONCKS CORNER SC 29461 $0.43 A E KNIGHT RT 1 BOX 661 99999 $18.00 A E MARTIN 24 PHANTOM DR DAYTON OH 45431 $50.95 -

Medieval Londoners Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M

IHR Conference Series Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU Text © contributors, 2019 Images © contributors and copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to re-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons license, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org or to purchase at https://www.sas.ac.uk/publications ISBN 978-1-912702-14-5 (hardback edition) 978-1-912702-15-2 (PDF edition) 978-1-912702-16-9 (.epub edition) 978-1-912702-17-6 (.mobi edition) This publication has been made possible by a grant received from the late Miss Isobel Thornley’s bequest to the University of London. -

Existing and Reserved Street Names

AllStreetName 10TH 11TH 12TH 13TH 14TH 15TH 16TH 17TH 18TH 19TH 1ST 20TH 21ST 22ND 23RD 24TH 25TH 26TH 27TH 28TH 29TH 2ND 30TH 3RD 417 419 426 434 436 46 46A 4TH 5TH 6TH 7TH 8TH 9TH A AAA ABACUS ABBA ABBEY ABBEYWOOD ABBOTSFORD ABBOTT ABELL ABERCORN ABERDEEN ABERDOVEY ABERNATHY ABINGTON ACACIA ACADEMY ACADEMY OAKS ACAPULCA ACKOLA ACORN ACORN OAK ACRE ACUNA ADAIR ADAMS ADDISON ADDISON LONGWOOD ADELAIDE ADELE ADELINE B TINSLEY WAY ADESA ADIDAS ADINA ADLER ADMIRAL ADONCIA ADVANCE AERO AFTON AGNES AIDEN AILERON AIMEE AIRLINE AIRMONT AIRPORT ALABASTER ALAFAYA ALAFAYA WOODS ALAMEDA ALAMOSA ALANS NATURE ALAQUA ALAQUA LAKES ALATKA ALBA ALBAMONTE ALBANY ALBAVILLE ALBERT ALBERTA ALBRIGHT ALBRIGHTON ALCAZAR ALCOVE ALDEAN ALDEN ALDER ALDERGATE ALDERWOOD ALDRUP ALDUS ALEGRE ALENA ALEXA ALEXANDER ALEXANDER PALM ALEXANDRIA ALFONZO ALGIERS ALHAMBRA ALINOLE ALLEGANY ALLEN ALLENDALE ALLERTON ALLES ALLISON ALLSTON ALLURE ALMA ALMADEN ALMERIA ALMOND ALMYRA ALOHA ALOKEE ALOMA ALOMA BEND ALOMA LAKE ALOMA OAKS ALOMA PINES ALOMA WOODS ALPEEN ALPINE ALPUG ALTAMIRA ALTAMONTE ALTAMONTE BAY CLUB ALTAMONTE COMMERCE ALTAMONTE SPRINGS ALTAMONTE TOWN CENTER ALTAVISTA ALTO ALTON ALVARADO ALVINA AMADOR AMALIE AMANDA AMANDA KAY AMARYLLIS AMAYA AMBER AMBER RIDGE AMBERGATE AMBERLEY AMBERLY JEWEL AMBERWOOD AMELIA AMERICAN AMERICAN ELM AMERICAN HOLLY AMERICANA AMESBURY AMETHYST AMHERST AMICK AMOUR DE FLAME AMPLE AMROTH ANACONDA ANASTASIA ANCHOR ANCIENT FOREST ANDERSON ANDES ANDOVER ANDREA ANDREW ANDREWS ANDREWS CESTA ANGEL TRUMPET ANGLE ANGOLA ANHINGA ANNA ANSLEY ANSON ANTELOPE -

A Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour a Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950

Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Sarah E Parker Grace & Favour 1 Published by Historic Royal Palaces Hampton Court Palace Surrey KT8 9AU © Historic Royal Palaces, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 1 873993 50 1 Edited by Clare Murphy Copyedited by Anne Marriott Printed by City Digital Limited Front cover image © The National Library, Vienna Historic Royal Palaces is a registered charity (no. 1068852). www.hrp.org.uk 2 Grace & Favour Contents Acknowledgements 4 Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Location of apartments 9 Introduction 14 A list of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace, 1750–1950 16 Appendix I: Possible residents whose apartments are unidentified 159 Appendix II: Senior office-holders employed at Hampton Court 163 Further reading 168 Index 170 Grace & Favour 3 Acknowledgements During the course of my research the trail was varied but never dull. I travelled across the country meeting many different people, none of whom had ever met me before, yet who invariably fetched me from the local station, drove me many miles, welcomed me into their homes and were extremely hospitable. I have encountered many people who generously gave up their valuable time and allowed, indeed, encouraged me to ask endless grace-and-favour-related questions. -

The Masons Arms, Teddington (See Page 35) Tel: 020 7281 2786

D ON ON L Feb Vol 33 Mar No 1 2011 The Masons Arms, Teddington (see page 35) Tel: 020 7281 2786 Steak & Ale House SET MENU SALE u 3 course meals for just £16! - or u 3 courses for just just £21 including a 10oz Sirloin or Rib- eye steak - or u A two course meal (starter and main or main and dessert) for just £11 So much choice there is something for ...Six Cask Marque everyone... oh, and Cask Marque accredited real ales accredited ales! always on tap and You can follow us on Facebook for all events and updates and on 40+ malt and blended Twitter@north_nineteen whiskies also now on. Membership discounts on ale available, All proper, fresh sign up at www.northnineteen.co.uk Steakhouse food. In the main bar: Food is served: Tuesday - Live music and open mic 8pm start Wednesday - Poker Tournament 7.30pm start Tuesday-Friday 5-10pm Dart board and board games always available Saturday 12-10pm Prefer a quiet pint? Sunday 12-7pm Our Ale and Whisky Bar is open daily for food, drinks and conversation. We always have six well Cask Marque Please book your Sunday Roast kept real ales and 40+ top quality whiskies. accredited There are no strangers here, just friends you haven’t met yet Editorial London Drinker is published by Mike Hammersley on behalf of the London Branches of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real NDO Ale Limited, and edited by Geoff O N Strawbridge. L Material for publication should preferably be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. -

Gleanings of Major Robert Thompson Namesake of Thompson CT

Gleanings of Major Robert Thompson (also known as Major Robert Thomson) Namesake of Thompson CT Assembled December 25, 2016 Thompson CT Editor: Joseph Iamartino On Behalf of the Thompson Historical Society © 2016 Thompson Historical Society, Joseph Iamartino – Editor Note: Permission granted by Professor Alan Thomson to use his Thomson document for purposes of this manuscript. Major Robert Thompson The Thompson Historical Society Foreword by Joseph Iamartino: In Book I, Professor Alan Thomson has assembled a remarkable biography of Major Robert Thompson. The Major was involved in many of the principal events in one of the most dramatic centuries in recorded history. However, the information about Robert Thompson had to be found, piece by piece, like a jigsaw puzzle scattered after a tornado. In our Internet age, it is easy to “Google up” information on a person but Prof. Thomson’s effort came the old fashioned way, laboriously finding and then reading the dusty texts, with one clue leading to another, assembling piece upon piece of a puzzle. The challenge for readers is to understand that many elements of the life of such a complex man as Robert Thompson, with activities in the American colonies, on the European continent, even in India, remain hidden to us even with Professor Thomson’s insights. It is up to us to assemble the story knowing there are huge gaps but, at least we now have a chance of understanding his story thanks to Professor Thomson’s labor of love. My son Christian, who was attending college in the UK at the time, and I visited Professor Thomson in London when Alan so generously donated his text to the Thompson Historical Society. -

A List of Books Found in the Wilsons' Home at Stepping Stones

The Library of Books found at Stepping Stones, the historic home of Bill and Lois Wilson AUTHOR TITLE DATE INSCRIPTIONS & NOTES "To dear Bill On your twentieth Anniversary 12/11/54 May a Kempis, Thomas My Imitation of Christ 1954 God bless you and love you and keep you always close to His Sacred Heart Sister M. Ignatia" "Christmas 1943 To Bill Wilson In grateful thanks and a Kempis, Thomas The Imitation of Christ 1943 gratitude for the hand in carrying on his work! 'Bill' Gardiner (sp) A.A. Portland, Oregon" Illegible "to-from" inscription on flyleaf, ending: "Mar 19th, A.D.T.W. Pansies 1888 1888" Abbott, Lawrence F. Twelve Great Modernists 1927 "Lois B. and William G. Wilson Merry Christmas to Lois & Abbott, Lyman Reminiscences 1915 Bill from Dad & Mother 1919" Abbott, Winston O. Have You Heard the Cricket Song 1971 "Bette Eaton Bossen" (illustrator "Winston O. Abbott" Adam, Karl The Spirit of Catholicism 1946 Adams, Henry John Randolph 1898 "Five Hundred Copies Printed Number (handwritten) 444" Adams, James Truslow The March of Democracy 1932 Adams, Richard Shardik 1974 Adams, Richard Watership Down 1975 Adams, Samuel Hopkins Canal Town 1944 Adler, Alfred Problems of Neurosis 1930 "Dr. Alfred Adler" Adler, Mortimer J. The Angels and Us 1982 "Skimmed thru this 11/3/86 L." The Days of Bruce: A Story from Scottish In various hands: "Leslie" "A.Molineux" "Mrs. L.S. Burnham Aguilar, Grace 1852 History Brooklyn, N.Y. August 5, 1852" In various hands: "Leslie" "Emma Burnham" "Mrs. L.S. Aguilar, Grace The Days of Bruce 1852 Burnham 1890" Aikman,