Last Days in the Desert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future of Values-Friendly Films — and Filmmaking

The (bright) future of values-friendly films — and filmmaking DeVon Franklin Dr. Jerry A. Johnson Rebecca Ver Dallas Jenkins Amy McGee Vincent Walsh Straten-McSparran A Special Report Prepared by The Washington Times Advocacy Department and Inspire Buzz Faith & Film The (bright) future of values-friendly films — and filmmaking Table of Contents Telling the story that faith is the path..................................................... 3 Breaking ground with national, DeVon Franklin multimedia ‘events’ for faith and family .............................................. 22 Spencer Proffer Values aren’t a niche ............................................................................... 6 Matthew Faraci ‘Dance’ film weaves four stories of hope ............................................. 23 Spencer Proffer Do we have faith in film? ......................................................................... 7 Dr. Jerry A. Johnson Faith. Film. And the stories we choose to tell ...................................... 24 Paul Aiello The (bright) future of faith-based films .................................................8 Cary Solomon and Chuck Konzelman Why Hollywood doesn’t get ‘faith’ films ............................................ 24 Dr. Larry W. Poland Viewing faith films as start-ups ..............................................................9 Harrison Powell Films help us ‘face and confront’ our core beliefs ............................... 25 Terry Botwick Storytelling and the power to change the world .................................12 -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H. -

Last Days in the Desert

Last Days in the Desert By John Mulderig Catholic News Service NEW YORK (CNS) – “Who do you say that I am?” As has often been pointed out, this question – originally posed by Jesus to the 12 Apostles – is in fact a decisive inquiry directed by the Savior at each and every human being. In crafting his thoughtful, but ultimately unsatisfying, religious drama “Last Days in the Desert” (Broad Green), writer-director Rodrigo Garcia attempts to sidestep this crucial issue of identity. His respectful ambivalence toward his possibly divine – but possibly merely human – protagonist not only undercuts the film’s appeal for believers, it creates some aesthetic confusion as well. The script embroiders on the biblical story of Jesus’ 40 days spent fasting and praying in the desert. Toward the end of that period, Garcia imagines an encounter between the Lord – here called by his Hebrew name, Yeshua, and played by Ewan McGregor – and a family of wilderness dwellers. Oppressed by prolonged solitude and by God’s apparent absence – the first line of dialogue is his plaintive cry, “Father, where are you?” – Yeshua, though initially wary of human contact, finds temporary relief in his interaction with the clan. Yet, as he becomes emotionally invested in their problems, the situation grows more complicated and the tone darker. The unnamed trio of relatives faces difficulties both spiritual and physical. The Father (Ciaran Hinds) and his teen son (Tye Sheridan) are in conflict over the lad’s future, while the Mother (Ayelet Zurer) is beset by an unidentified illness that seems certain to prove fatal. -

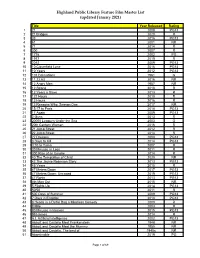

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (Updated January 2021)

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (updated January 2021) Title Year Released Rating 1 21 2008 PG13 2 21 Bridges 2020 R 3 33 2016 PG13 4 61 2001 NR 5 71 2014 R 6 300 2007 R 7 1776 2002 PG 8 1917 2019 R 9 2012 2009 PG13 10 10 Cloverfield Lane 2016 PG13 11 10 Years 2012 PG13 12 101 Dalmatians 1961 G 13 11.22.63 2016 NR 14 12 Angry Men 1957 NR 15 12 Strong 2018 R 16 12 Years a Slave 2013 R 17 127 Hours 2010 R 18 13 Hours 2016 R 19 13 Reasons Why: Season One 2017 NR 20 15:17 to Paris 2018 PG13 21 17 Again 2009 PG13 22 2 Guns 2013 R 23 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 2003 G 24 20th Century Women 2016 R 25 21 Jump Street 2012 R 26 22 Jump Street 2014 R 27 27 Dresses 2008 PG13 28 3 Days to Kill 2014 PG13 29 3:10 to Yuma 2007 R 30 30 Minutes or Less 2011 R 31 300 Rise of an Empire 2014 R 32 40 The Temptation of Christ 2020 NR 33 42 The Jackie Robinson Story 2013 PG13 34 45 Years 2015 R 35 47 Meters Down 2017 PG13 36 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 2019 PG13 37 47 Ronin 2013 PG13 38 4th Man Out 2015 NR 39 5 Flights Up 2014 PG13 40 50/50 2011 R 41 500 Days of Summer 2009 PG13 42 7 Days in Entebbe 2018 PG13 43 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag a Mindless Comedy 2000 R 44 8 Mile 2003 R 45 90 Minutes in Heaven 2015 PG13 46 99 Homes 2014 R 47 A.I. -

Critical Reception of Contemporary Biblical Film Adaptations Adaptations Film Biblical Contemporary of Criticalreception

GÖZDE UĞURGÖZDE ÖZBUDAK CRITICAL RECEPTION OF CONTEMPORARY BIBLICAL FILM ADAPTATIONS CRITICAL RECEPTIONCRITICAL OF CONTEMPORARY BIBLICAL FILM ADAPTATIONS A Master’s Thesis by GÖZDE UĞUR ÖZBUDAK Department of Communication and Design İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara Bilkent University 2020 University Bilkent December 2020 To those who dream CRITICAL RECEPTION OF CONTEMPORARY BIBLICAL FILM ADAPTATIONS The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by GÖZDE UĞUR ÖZBUDAK In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN MEDIA AND VISUAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND DESIGN İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY Ankara December 2020 ABSTRACT CRITICAL RECEPTION OF CONTEMPORARY BIBLICAL FILM ADAPTATIONS Özbudak, Gözde Uğur M.A. Department of Communication and Design Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Colleen Kennedy-Karpat December 2020 In this thesis, the reception of biblical adaptations is analyzed. By using reception studies, critical discourse analysis and close reading methods; The Passion of the Christ (2004), Mary Magdalene (2018), Noah (2014), Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), A Serious Man (2009) and mother! (2017) are analyzed with how the biblical stories are adapted into cinema and what kind of reception they have received from the reviewers. These reviews gathered from American Christian websites and professional film reviews published on popular media, most of which are American, are analyzed and found whether the fidelity criticism is still existing among the film viewers. In this regard, this thesis argues that the Christian members of the audience members expect to see textual fidelity in the biblical adaptations and the lack of it causes films to receive harsh criticism whereas the professional critics are more invested in analyzing the films for their cinematic qualities. -

Satan’S Character in the Hebrew Tanak and Christian New Testament

Learning outcomes • To learn about the development of Satan’s character in the Hebrew Tanak and Christian New Testament. • To look at some examples of Satan in popular culture. • Lucifer • Satan in Jesus movies • Essay advice Office hours this week • Wednesday 2-4pm, Arts Student Centre study space (level 4, HSB) • Thursday 10-11am, Science building foyer (outside lecture theatre) • Thursday 2-4pm, Arts Student Centre study space (level 4, HSB) • Tuaakana support (contact David or myself) • Get in touch if you want to see me outside these times Essay advice • Writing style - can be formal or more informal (think of a well-written, engaging blog post). • You can use first person – ‘in this essay, I will …) • Writing – PROOFREAD YOUR ESSAY • Use Spell Check at the very least • Read it aloud – does it sound okay? • Get a friend to read it – does it make sense to them? • Come see me or your Tuaakana tutor for help • Referencing • Include a bibliography/reference list at end of essay • Use whatever referencing style you’re used to (e.g. APA, Chicago, etc.) • See http://www.cite.auckland.ac.nz/2.html for help • It’s important to get your referencing right. Essay advice • Don’t’ waste too much time retelling Bible stories or movie plots – that takes up precious words. • Assume the reader knows the Bible story • Assume the reader is less familiar with your cultural text (e.g. film, music, person) so give enough information to make your points clearly • Your introduction should be short and sharp, clearly highlighting your essay focus – start with a catchy first sentence! • Conclusion can be short too • Don’t summarize what you’ve done in too much detail (we know what you’ve done!) • Avoid including new information, but you can reflect on some of the issues you’ve covered in your discussion and how they raise new questions about the topic (so, what are the implications of your findings – what should we look at next?). -

Ewan Mcgregor Plays Dual Role in Acclaimed Writer/Director Rodrigo Garcia’S Drama ‘Last Days in the Desert’

For Immediate Release: EWAN MCGREGOR PLAYS DUAL ROLE IN ACCLAIMED WRITER/DIRECTOR RODRIGO GARCIA’S DRAMA ‘LAST DAYS IN THE DESERT’ TYE SHERIDAN STARS ALONGSIDE CIARÁN HINDS AND AYELET ZURER MOCKINGBIRD PICTURES AND DIVISION FILMS COMMENCE PRINCIPAL PHOTOGRAPHY ON PROJECT Los Angeles, CA (February 5, 2014) – Mockingbird Pictures and Division Films announce today that Ewan McGregor and Tye Sheridan have signed on to star in their co-production of LAST DAYS IN THE DESERT, which is written and directed by Rodrigo Garcia (Albert Nobbs). Ciarán Hinds (There Will Be Blood) and Ayelet Zurer (Angels and Demons) round out the film’s cast as Sheridan’s Father and Mother. LAST DAYS IN THE DESERT follows a holy man and a demon—both roles played by McGregor—on a journey through the desert. An encounter with a family struggling to survive in this harsh environment forces the holy man to confront his own fate. The film is produced by Julie Lynn and Bonnie Curtis of Mockingbird Pictures along with Wicks Walker of Division Films, who financed the picture in collaboration with recently shingled Ironwood Entertainment, with Aspiration Media and New Balloon in association. The film has commenced principal photography in the Southern California desert. Garcia and director of photography “Chivo” Lubezki are reunited for the picture after having worked together many years ago on Garcia’s Things You Can Tell Just by Looking at Her, which was awarded Un Certain Regard at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival. Lubezki received his sixth Academy Award nomination recently for his work on Gravity. WME Entertainment is handling domestic rights, with Hanway Films representing international. -

Sermon Transcript

40 Days in the Desert: Faith Formed in the Wilderness | Lent 2018 It’s Not About You (2 of 6) February 25, 2018 This is the second Sunday of Lent and so week 2 of our 6-week sermon series, 40 Days in the Desert: Faith Formed in the Wilderness. I’m glad that you could be with us in worship this morning as we continue to look at Jesus’ time in the desert… the lessons we can learn from his experiences and from the way he responds to having his identity and calling tested by the enemy. Last Sunday we began this series with a message called, Welcome to the Wilderness, where we saw how the Spirit sent Jesus into the desert after his baptism, after he is confirmed as God’s beloved Son, the Messiah, to eventually offer himself as a sacrifice for the sins of the world. And not only was Jesus’ time in the wilderness something the Father wanted for shaping and preparing him for his mission, but we also looked at how God wants to do the same for us at various times in our Christian journey. So, last week we were invited to see hardships and trials, or spiritually dry and barren seasons of life, as discipline from a loving parent. In other words, it is for training us and forming us to become mature in our faith. Therefore, it is right to see the wilderness as an opportunity to deepen our commitment and trust in God, for the Spirit to reveal what’s in our hearts, and for us to decide whether we’re going to be and do what God wants, or shrink back and do what we want instead. -

WSKG Television

However, this ancient relationship one roof. Based on the award- was not lost altogether and winning Marketplace radio series continues uninterrupted in just one "One School, One Year," OYLER location -- on the northern edge of takes viewers through a year at the the continent's central plains in a school, focusing on Hockenberry's place named Wood Buffalo mission to transform a community National Park. Today the ancestors and on senior Raven Gribbins' of those ancient buffalo and wolves quest to be the first in her troubled WSKG-DT2 still engage in epic life and death family to finish high school and go dramas across this northern land. to college. When Hockenberry's job January 2017 Packs of wolves up to 30 strong is threatened, it becomes clear it's expanded listings hunt the largest land mammals on a make-or-break year for both of the continent -- buffalo. By getting them. to know a specific pack of wolves 10pm Doc World NOTE: WSKG will and the individuals that make up Among The Believers discontinue the pack, we get a sense of how Charismatic cleric Abdul Aziz these two animal species (wolves Ghazi, an ISIS supporter and broadcasting the and buffalo) live together in what Taliban ally, is waging jihad against “World” channel seems like a forgotten corner of the the Pakistani state. His dream is to February 1, in favor of world. impose a strict version of Shariah 9pm Oyler: One School, One law throughout the country, as a adding the new 24/7 PBS Year model for the world. -

Cinematic Childhood(S) and Imag(In)Ing the Boy Jesus: Adaptations of Luke 2:41-52 in Late Twentieth-Century Film

CINEMATIC CHILDHOOD(S) AND IMAG(IN)ING THE BOY JESUS: ADAPTATIONS OF LUKE 2:41-52 IN LATE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FILM by JAMES MAGEE Master of Arts, Vancouver School of Theology, 2011 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN BIBLICAL STUDIES in the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY May 2019 © James Magee, 2019 Cinematic Childhood(s) and Imag(in)ing the Boy Jesus: Adaptations of Luke 2:41-52 in Late Twentieth-Century Film Abstract Despite sustained academic examinations of Jesus in film over the past couple of decades, as well as biblical scholars’ multidisciplinary work in the areas of children’s and childhood studies, the cinematic boy Jesus has received little attention. This thesis begins to fill the lacuna of scholarly explorations into cinematic portrayals of Jesus as a child by analyzing two adaptations of Luke’s story of the twelve-year- old Jesus in late twentieth-century film. Using methods of historical and narrative criticism tailored to the study of film, I situate the made-for-television movies Jesus of Nazareth (1977) and Jesus (2000) within the trajectories of both Jesus films and depictions of juvenile masculinity in cinema, as well as within their respective social, cultural and historical contexts. I demonstrate how these movie sequences are negotiations by their filmmakers between theological and historical concerns that reflect contemporary ideas about children and particular idealizations about boyhood. ii For Michael iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements . v Abbreviations . vi Chapter 1 Searching for the Boy Jesus: A Neglected Area of Jesus-in-Film Scholarship .