Pacificnwcons00fiddrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

"His Trick Knee Is Acting up Again!"

------------_.__ ._------- ..... Will Somebody Tell The PresideDt To Stop Bombing Tlte Parly? RIPON MARCH 1, 1974 Vol. X, No.5 ONE DOLLAR "HIS TRICK KNEE IS ACTING UP AGAIN!" , CONTENTS Commentary Features Weasel Words and Party Principle ............ 4 Politics: Reports .................................................. 8 In an age of political doublespeak, the ritqJallstic State Reports on Florida, New Mexico, Rhode Is compilation of party platforms seems ripe ~9r re land, New Jersey, and Ohio. form. Michigan State Rep. Michael DivelY (R) proposes that a "statement of the majority" be submitted for the quadrennial platforms. Dively served as the chairman of the Revision and Devel Politics: Profiles .................................................... 11 opment Committee of the Michigan GOP, which recommended a similar step for that state party. u.s. Rep. Albert Quie of Minnesota, ranking Re publican member of the House Education and Labor Committee: the profile was prepared by Paul Anderson of the Minnesota Chapter. Constitutional Imbalance ................................ 5 Sen. Charles McC. Mathias (R-Md.) has been c0- chairman, along with Sen. Frank Church (D Politics: People .................................................... 12 Idaho), of the Special Committee on the Termina tion of the National Emergency. According to Mathias, the laxity of controls over emergency presidential powers applies equally to other legis Letters ...................................................................... 14 lation, and he urges that -

Ihii^^^^Bim^^Mmmi L! V

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Washington COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Snohomish INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———OCT 28 COMMON: Snohomish Historic District AND/OR HISTORIC: Snohomish City STREET AND, NUMBER: ..P A /l_/ J5>1<3 CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Snohomish #2 - Honorable Lloyd Meeds Washington 53 Snohomish 061 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC IXl District Q Building Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: E Restricted D Site [J Structure Private [~~1 In Process 1i—i _| Unoccupiedii • j "^ . _ . (vl Unrestricted a object n B°th [ | Being Considered Preservation work ^ in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Q Agricultural C8 Government Park I I Transportotion [~~1 Comments [S Commercial CD Industrial Private Residence D Other (Specify) Q Educational CH Mil tary Religious (2J Entertainment SI Museum Scientific OWNER'S NAME: * > Multiple ownership P> H « „ STREET AND NUMBER: H- 3 Cl TY OR TOWN: IHii^^^^BiM^^MMMi COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Snohomish County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: Wetmore Avenue CITY OR TOWN: Everett Washington 53 <s TITLE OF SURVEY: None DATE OF SURVEY: n Federal Q State «X'Z DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: :\ STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: L! V- (Check One) D Excellent 1 XJ Good Q Fair [ I Deteriorated CD Ruins O Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) |£] Altered 1 I Unaltered D Moved [X] Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Snohomish is located in Snohomish County, Washington, some 30 miles northeast of Seattle and on the north bank of the Snohomish River. -

Style Specifications

Site Soundscapes Landscape architecture in the light of sound Per Hedfors Department of Landscape Planning Ultuna Uppsala Doctoral thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2003 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae Agraria 407 ISSN 1401-6249 ISBN 91-576-6425-0 © 2003 Per Hedfors, Uppsala Tryck: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2003 Abstract Hedfors, Per. 2003. Site Soundscapes – landscape architecture in the light of sound. Doctor’s dissertation. issn 1401-6249, isbn 91-576-6425-0. This research was based on the assumption that landscape architects work on pro- jects in which the acoustic aspects can be taken into consideration. In such projects activities are located within the landscape and specific sounds belong to specific activities. This research raised the orchestration of the soundscape as a new area of concern in the field of landscape architecture; a new method of approaching the problem was suggested. Professionals can learn to recognise the auditory phenom- ena which are characteristic of a certain type of land use. Acoustic sources are obvious planning elements which can be used as a starting point in the develop- ment process. The effects on the soundscape can subsequently be evaluated according to various planning options. The landscape is viewed as a space for sound sources and listeners where the sounds are transferred and coloured, such that each site has a specific soundscape – a sonotope. This raised questions about the landscape’s acoustic characteristics with respect to the physical layout, space, material and furnishing. Questions related to the planning process, land use and conflicts of interest were also raised, in addition to design issues such as space requirements and aesthetic considerations. -

Business Name Phone Email Address 1 City Business Description

Business Name Phone Email Address 1 City Business Description Certification Type Janitorial cleaning,office cleaning, window cleaning, carpet extraction and cleaning, floor sealing and stripping, emergency clean up, power washing and 1 Clean Conscience 612-702-9603 [email protected] 15478 Pennock Lane Apple Valley more. SBE Janitorial cleaning,office cleaning, window cleaning, carpet extraction and cleaning, floor sealing and stripping, emergency clean up, power washing and 1 Clean Conscience 612-702-9603 [email protected] 15478 Pennock Lane Apple Valley more. WBE NAICS 811121: Automotive Body, Paint, and Interior Repair and Maintenance; NAICS 811198: All Other Automotive 1 Stop Auto Care, LLC 651-292-1485 [email protected] 159 W. Pennsylvania Avenue Saint Paul Repair and Maintenance MBE NAICS 811121: Automotive Body, Paint, and Interior Repair and Maintenance; NAICS 811198: All Other Automotive 1 Stop Auto Care, LLC 651-292-1485 [email protected] 159 W. Pennsylvania Avenue Saint Paul Repair and Maintenance SBE 1Source Holdings, LLC 612-868-1743 [email protected] 4250 Norex Drive Chaska Office Furniture Store SBE Architectural and interior planning and 292 Design Group Inc 612-767-3773 [email protected] 3533 East Lake Street Minneapolis design SBE Landscaping, Janitorial, Flooring, Cabinet 3 Chicks & A Hammer 612-701-9116 [email protected] 1800 Queen Ave No Minneapolis installation, Counter top installation. MBE Landscaping, Janitorial, Flooring, Cabinet 3 Chicks & A Hammer 612-701-9116 [email protected] 1800 Queen Ave No Minneapolis installation, Counter top installation. SBE Landscaping, Janitorial, Flooring, Cabinet 3 Chicks & A Hammer 612-701-9116 [email protected] 1800 Queen Ave No Minneapolis installation, Counter top installation. -

Class of 1965 50Th Reunion

CLASS OF 1965 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1965 Abby Goldstein Arato* June Caudle Davenport Anna Coffey Harrington Catherine Posselt Bachrach Margo Baumgarten Davis Sandol Sturges Harsch Cynthia Rodriguez Badendyck Michele DeAngelis Joann Hirschorn Harte Isabella Holden Bates Liuda Dovydenas Sophia Healy Helen Eggleston Bellas Marilyn Kirshner Draper Marcia Heiman Deborah Kasin Benz Polly Burr Drinkwater Hope Norris Hendrickson Roberta Elzey Berke Bonnie Dyer-Bennet Suzanne Robertson Henroid Jill (Elizabeth) Underwood Diane Globus Edington Carol Hickler Bertrand* Wendy Erdman-Surlea Judith Henning Hoopes* Stephen Bick Timothy Caroline Tupling Evans Carla Otten Hosford Roberta Robbins Bickford Rima Gitlin Faber Inez Ingle Deborah Rubin Bluestein Joy Bacon Friedman Carole Irby Ruth Jacobs Boody Lisa (Elizabeth) Gallatin Nina Levin Jalladeau Elizabeth Boulware* Ehrenkranz Stephanie Stouffer Kahn Renee Engel Bowen* Alice Ruby Germond Lorna (Miriam) Katz-Lawson Linda Bratton Judith Hyde Gessel Jan Tupper Kearney Mary Okie Brown Lynne Coleman Gevirtz Mary Kelley Patsy Burns* Barbara Glasser Cynthia Keyworth Charles Caffall* Martha Hollins Gold* Wendy Slote Kleinbaum Donna Maxfield Chimera Joan Golden-Alexis Anne Boyd Kraig Moss Cohen Sheila Diamond Goodwin Edith Anderson Kraysler Jane McCormick Cowgill Susan Hadary Marjorie La Rowe Susan Crile Bay (Elizabeth) Hallowell Barbara Kent Lawrence Tina Croll Lynne Tishman Handler Stephanie LeVanda Lipsky 50TH REUNION CLASS OF 1965 1 Eliza Wood Livingston Deborah Rankin* Derwin Stevens* Isabella Holden Bates Caryn Levy Magid Tonia Noell Roberts Annette Adams Stuart 2 Masconomo Street Nancy Marshall Rosalind Robinson Joyce Sunila Manchester, MA 01944 978-526-1443 Carol Lee Metzger Lois Banulis Rogers Maria Taranto [email protected] Melissa Saltman Meyer* Ruth Grunzweig Roth Susan Tarlov I had heard about Bennington all my life, as my mother was in the third Dorothy Minshall Miller Gail Mayer Rubino Meredith Leavitt Teare* graduating class. -

Great American Outdoors Act Projects Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area

Great American Outdoors Act projects Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area Mountains to Sound Greenway-Heritage Area Multi Asset Recreation Investment Corridor The Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area is an iconic 1.5 million-acre landscape in Washington State, stretching across the Cascade Mountains from Central Washington to Puget Sound in Seattle. The Greenway promotes a healthy and sustainable relationship between people and nature by providing nearby parks and trails, connected wildlife habitat, places for culture and tradition, world-class outdoor recreation and education, working forests and local agricultural production, and thriving communities. The Greenway is valued by a broad cross-section of society, working together as an effective coalition to conserve this place and its heritage for future generations. When Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act in 2020, we knew how important this legislation would be to the state of Washington. For 30 years the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust has witnessed the positive impact access to nature brings to the region for public health, habitat and wildlife, and local economies. Many public agencies, nonprofit organizations, and individuals have worked tirelessly to sustain this abundant access to nature, with outdoor recreation gaining popularity each year. As public agency budgets and staff simultaneously shrink, the backlog of much-needed maintenance for trails and recreation areas has grown dramatically. The Great American Outdoors Act offers part of the solution to this maintenance backlog for public land management agencies, and will benefit all people who live, work and play in the Mountains to Sound Greenway and in public lands across the country. -

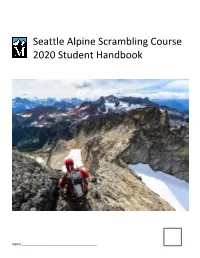

Seattle Alpine Scrambling Course 2020 Student Handbook

Seattle Alpine Scrambling Course 2020 Student Handbook Name __________________________________________ On the cover Photograph by Luke Helgeson Dumbell Mountain Seattle Alpine Scrambling Course – Student Handbook p 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ............................................................... 4 COURSE TIMELINE ........................................................... 5 GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS ....................................... 6 COURSES AND BADGES REQUIRED TO GRADUATE ......... 7 RESPONSIBILITIES AND CLUB POLICIES ........................... 8 THE MOUNTAINEERS’ EMERGENCY PLAN ...................... 9 COURSE EXPECTATIONS - WORKSHOPS ........................ 10 COURSE EXPECTATIONS – FIELD TRIPS ......................... 11 COURSE EXPECTATIONS – EXPERIENCE TRIP ................ 12 CONDITIONING ............................................................. 13 CONDITIONING LOG ...................................................... 14 CHECKLIST – PRE-COURSE ............................................. 15 CHECKLIST – PRE-TRIP ................................................... 15 SCRAMBLE PACKING LIST .............................................. 16 10 ESSENTIALS ............................................................... 17 REQUIRED SCRAMBLING GEAR ..................................... 19 CAR KIT .......................................................................... 22 SUGGESTED GEAR ........................................................ -

The Geometry of Journalism

The Geometry of Journalism Zohar Bowen Bronet Supervisor: Professor Carles Roca-Cuberes Final Thesis for the Master’s in International Studies on Media, Power and Difference Department of Communication Universitat Pompeu Fabra 2019/2020 1 Abstract: Scholars from multiple disciplines have been studying various aspects of journalism for nearly a century. The question of newsworthiness, what becomes news and what does not, has always been an area of great interest. While many explanations have been offered, all include varying degrees of psychology and teleology. So far, none have approached the subject using sociologist Donald Black’s framework of pure sociology. The paradigm predicts and explains the behavior of social life with the shape of social space it occurs in, its geometry. Here, I apply Black’s model to the question of newsworthiness to identify the social structures journalism occurs in, and how it behaves within them. I then extend the model to the moral nature of journalism by studying it as a form of social control. The result is a set of theoretical formulations about the behavior of journalism, and a new sociological theory of journalism. Key words: journalism, pure sociology, social geometry, newsworthiness, social control 2 Introduction 3 Pure Sociology and Journalism as a Dependent Variable 4 Social Status 6 Movements of Social Time 6 Journalism as Evaluation 8 Quantifying Journalism 9 PART I Theories of Newsworthiness 11 Events 11 Outlets and Audiences 12 Broader Context and a New Theory 14 Principles of Journalism -

THE FOLEY REPORT Director’S Update

2018 Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson “Defending the Dreamers” Page 16 THE FOLEY REPORT Director’s Update In 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary chose “populism” as its word of the year. In recent years, movements like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street thrived, and populist Director Cornell W. Clayton politicians like Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, Sarah 316 Bryan Hall Palin, and Elizabeth Warren have become political stars. Washington State University PO Box 645136 In Europe, Britain voted to leave the EU, populist Cornell Clayton Pullman, WA 99164-5136 politicians like Marine Le Pen in France or Boris Phone 509-335-3477 Johnson in the UK became famous, while Italy, Hungary, Greece and Poland have all elected [email protected] populist governments. foley.wsu.edu Established at Washington State University We are in a populist moment, but what is populism? What explains its growing appeal? And in 1995, the mission of the institute should it concern us? The Foley Institute has hosted several events in recent years exploring is to foster congressional studies, civic various aspects of populist politics, and so I thought I would use my note today to share some education, public service, and public thoughts on this topic. policy research in a non-partisan, cross-disciplinary setting. First, populism is not an ideology that is committed to specific political goals or policies. Rather, it is a style of political discourse or thinking, one which views politics as a conflict Distinguished Professors between corrupt elites (political, economic, intellectual or cultural) and a virtuous “people” Cornell W. Clayton, (the silent majority, the forgotten man, “real” Americans). -

Jolene Unsoeld PDF.Indd

JOLENE UNSOELD “Un-sold” www.sos.wa.gov/legacy who ARE we? | Washington’s Kaleidoscope Jolene addresses an anxious group of employees at Hoquiam Plywood Company in 1988 as the uncertainty over timber supplies intensifies. Kathy Quigg/The Daily World Introduction: “The Meddler” imber workers in her district were mad as hell over set- asides to protect the Northern Spotted Owl. Rush Lim- Tbaugh branded her a “feminazi.” Gun-control advocates called her a flip-flopper. It was the spring of 1994 and Con- gresswoman Jolene Unsoeld of Olympia was girding for the political fight of her life. CSPAN captured her in a bitter de- bate with abortion opponents. Dick Armey, Newt Gingrich’s sidekick, was standing tall in his armadillo-skin cowboy boots, railing against the “self-indulgent conduct” of women who had been “damned careless” with their bodies. As other Republi- cans piled on, Unsoeld’s neck reddened around her trademark pearl choker. Men just don’t get it, she shot back. “Reproductive health is at the very core of a woman’s existence. If you want to be brutally frank, what it compares with is if you had health- care plans that did not cover any illness related to testicles. I “Un-sold” 3 think the women of this country are being tolerant enough to allow you men to vote on this!” Julia Butler Hansen, one of Jolene’s predecessors repre- senting Washington’s complicated 3rd Congressional District, would have loved it. Brutally frank when provoked, Julia was married to a logger and could cuss like one. -

Hiking Withdogs

www.wta.org April 2008 » Washington Trails On Trail « Hiking withDogs Photo by “Sadie’s Driver” Dogs make some of the finest hiking companions. Sadie hikes with her “driver” on the Yellow Aster Butte Trail. Hiking with Your Best Buddy The Northwest is blessed with so many but sometimes that pushed her to the limits. places to venture in the outdoors—no matter Like the time I decided to do a trail run to the what your skill level. And, for some, it’s so top of Mount Dickerman in August. Not real much more enjoyable when you have a four- smart. She collapsed about a mile from the car legged companion to join you. The dogs I have on our way down. The combination of heat and seen on the trail seem so happy to be out roam- insufficient water took its toll. We made it back ing with their humans. fine, but I learned a lesson. Having hiked for a number of years all Some dogs are comfortable rock hopping around Washington and areas in British Colum- and scrambling, but many are not. Sadie could bia, my greatest enjoyment has been with my climb higher and faster than I could, but I al- Sadie’s buddy Sadie. This was a she-devil golden re- ways worried about what would happen when triever who, as a puppy, was a terror! But from she got to the top. Fortunately Sadie was quite Driver Sadie’s Driver lives her very first trip, being on the trail brought out confident on her feet and was cautious enough her best.