The Feast of Corpus Christi in the West Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diocese News March 20

SERVING WITH JOY GOOD NEWS FROM THE DIOCESE OF EXETER | march 2020 Reverend Nick Haigh talks about JOY 2020 Inside: and the need to engage with people outside JOY 2020 our church walls KEY DATES FAMILY FUN COOKING CLUB “We have been looking for and recipe cards for families to ways in which we can support pop in and collect for free during families in the holidays with food. the school holidays or at other “We talked to foodbanks and times of the year. schools and found out that A #familyfuncookingclub some families aren’t going to Instagram account has been foodbanks because that’s not set-up for families to share their what they do. culinary creations. “Others can’t get to them Tatiana says: “We are hoping because of the distance they Family Fun Cooking Club will have to travel. It’s preventing enable all families, wherever they them from accessing food for are in Devon, to access good The recipes include: Baked their families.” ingredients to cook a family meal Porridge, Lentil Dhal, Hot Dog Tatiana Wilson is the Education together.” Spaghetti, Green Pasta Bake Advisor for projects and For more information and to and Microwave Mug Cake. vulnerable pupils at the Church download recipe cards go to: Merenna says: “All the recipes of England in Devon. https://exeter.anglican.org/ have been developed using She has taken a pilot project resources/faith-action/family- really basic ingredients which from the West Exmoor Federation fun-cooking-club/ or email are readily available in shops and of schools in North Devon and [email protected] foodbanks. -

I. History of the Feast of Corpus Christi II. Theology of the Real Presence III

8 THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 PASTORAL LETTER [email protected] [email protected] PASTORAL LETTER THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 9 The Real Presence: Life for the New Evangelization To the priests, deacons, religious and [6] From the earliest times, the Eucharist III. Practical Reflections all the faithful: held a special place in the life of the Church. St. Ignatius, who, as a boy, had heard St. John [9] This faith in the Real Presence moves N the Solemnity of the Most preach and knew St. Polycarp, a disciple of St. us to a certain awe and reverence when we Holy Body and Blood of Christ, John, said, “I have no taste for the food that come to church. We do not gather as at a civic I wish to offer you some perishes nor for the pleasures of this life. I assembly or social event. We are coming into theological, historical and want the Bread of God which is the Flesh of the Presence of our Lord God and Savior. The O practical reflections on the Christ… and for drink I desire His Blood silence, the choice of the proper attire (i.e. not Eucharist. The Eucharist is which is love that cannot be destroyed” (Letter wearing clothes suited for the gym, for sports, “the culmination of the spiritual life and the goal to the Romans, 7). Two centuries later, St. for the beach and not wearing clothes of an of all the sacraments” (Summa Theol., III, q. 66, Ephrem the Syrian taught that even crumbs abbreviated style), even the putting aside of a. -

Divine Worship Newsletter

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON Divine Worship Newsletter The Presentation - Pugin’s Windows, Bolton Priory ISSUE 5 - FEBRUARY 2018 Introduction Welcome to the fifth Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter will be eventually available as an iBook through iTunes but for now it will be available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected] just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. In this issue we continue a new regular feature which will be an article from the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of His Holiness. Under the guidance of Msgr. Guido Marini, the Holy Father’s Master of Ceremonies, this office has commissioned certain studies of interest to Liturgists and Clergy. Each month we will publish an article or an extract which will be of interest to our readers. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and treat topics that interest you and perhaps others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

Draft Scheme and a Glossary of All Terms Used

Revd Dr Adrian Hough Exeter Diocesan Mission and Pastoral Secretary The Old Deanery Exeter EX1 1HS 01392 294910 [email protected] 22nd October 2020 Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Diocese of Exeter The Benefice of Honiton, Gittisham, Combe Raleigh, Monkton, Awliscombe and Buckerell The Benefice of Offwell, Northleigh, Farway, Cotleigh and Widworthy The Benefice of Colyton, Musbury, Southleigh and Branscombe The Benefice of Broadhembury, Dunkeswell, Luppitt, Plymtree, Sheldon, and Upottery The Bishop of Exeter has asked me to publish a draft Pastoral Scheme in respect of pastoral proposals affecting the above parishes. I attach a copy of the draft Scheme and a glossary of all terms used. I am sending a copy to all the statutory interested parties, as the Mission and Pastoral Measure requires, and any others with an interest in the proposals. Anyone may make representations for or against all or any part or parts of the Draft Scheme and should send them so as to reach the Church Commissioners at the following address no later than midnight on Monday 7th December 2020. Rex Andrew Church Commissioners Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ (email [email protected]) (tel 020 7898 1743) Representations may be sent by post or e-mail (although e-mail is preferable at present) and should be accompanied by a statement of your reasons for making the representation. If the Church Commissioners have not acknowledged receipt of your representation before the above date, please ring or e-mail them to ensure it has been received. For administrative purposes, a petition will be classed as a single representation and they will only correspond with the sender of the petition, if known, or otherwise the first signatory – “the primary petitioner”. -

The Axe Valley Mission Community Profile for Recruitment of a New Priest in Charge at Uplyme and Axmouth and Team Vicar Across the Axe Valley Mission Community

The Axe Valley Mission Community Profile for recruitment of a new Priest in Charge at Uplyme and Axmouth and Team Vicar across the Axe Valley Mission Community. November 2019 1 Contents Archdeacon’s Foreword 3 Introduction 5 Vision of the Axe Valley Mission Community and the new role 6 Person specification and accommodation 7 Churches within the AVMC and communication within AVMC 8 Profiles of the churches St Michael’s Church, Axmouth 9 The Church of St Peter and St Paul, Uplyme 10 All Saints’ Church, All Saints 11 Holy Cross Church, Woodbury 12 St Andrew’s Church, Chardstock 13 St John Baptist, Membury 14 The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Combpyne and Rousdon 15 St Mary the Virgin, Axminster (The Minster) 16 2 Growing in prayer Making new disciples Serving the people of Devon with joy The Archdeacon’s Foreword The Ven. Andrew Beane, Archdeacon of Exeter e. [email protected] t. 01392 425577 ___________________________________________________________________________ Thank You Thank you for your interest in the role of Priest-in-Charge at Uplyme and Axmouth (Team Vicar Designate in the Axe Valley Mission Community). This is a new collaborative post as we explore a enhanced team ministry centered around the historic market town of Axminister. The person appointed will have pastoral responsibility for the parishes of Uplyme and Axmouth, and a wider leadership brief across the Mission Community for work with children, youth and families. Our Diocesan Vision We seek to be people who together are: Growing in Prayer Prayer is conversation with God and is part of a healthy Christian life. -

CARNIVAL and OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, USA and Britain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE CARNIVAL AND OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, U.S.A. and Britain: a selected bibliographical index by John Cowley First published as: Bibliographies in Ethnic Relations No. 10, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, September 1991, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL John Cowley has published many articles on blues and black music. He produced the Flyright- Matchbox series of LPs and is a contributor to the Blackwell Guide To Blues Records, and Black Music In Britain (both edited by Paul Oliver). He has produced two LPs of black music recorded in Britain in the 1950s, issued by New Cross Records. More recently, with Dick Spottswood, he has compiled and produced two LPs devoted to early recordings of Trinidad Carnival music, issued by Matchbox Records. His ‗West Indian Gramophone Records in Britain: 1927-1950‘ was published by the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations. ‗Music and Migration,‘ his doctorate thesis at the University of Warwick, explores aspects of black music in the English-speaking Caribbean before the Independence of Jamaica and Trinidad. (This selected bibliographical index was compiled originally as an Appendix to the thesis.) Contents Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 7 How to use this index 8 Bibliographical index 9 Bibliography 24 Introduction The study of the place of festivals in the black diaspora to the New World has received increased attention in recent years. Investigations range from comparative studies to discussions of one particular festival at one particular location. It is generally assumed that there are links between some, if not all, of these events. -

May 2021 Mustardseed

- A GRAIN OF MUSTARDSEED - Dear Friends in Christ: May 2021 Notwithstanding the continued strictures of the COVID-19 pandemic (vaccinations numbers are up, but so are reported infections in our County and region), May brings a season of religious feasting and celebration: We call to remembrance many of the saving acts of our Lord and Savior; we commemorate the lives and sacrifices of saints and saintly brethren, we pray, as is particularly timely this year, for God’s renewal of His creation. St. Philip and St. James’ Feast is kept with Holy Communion on Saturday, the 1st. Rogation Sunday is on the 9th and we observe the day by singing the Litany in Procession around the precincts of our property (current protocols allow to ‘belt it out’ when outside and wearing masks…so let’s do our best!). In so doing we pray God’s blessing upon his creation in this place wherein He has called us to proclaim Christ’s renewing grace. The three Rogation Days (from the Latin “rogare:” “to ask/pray”) follow, bringing us to the close of Eastertide on Ascension Day on Thursday the 13th (Communion services at 10:00 am and 7:00 pm). Ten days of Ascensiontide carry us to Whitsunday (Pentecost) on the 23rd and the octave of that feast gives us Whit Monday, Whit Tuesday and then three Ember Days on the 26th, 28th and 29th. The Feast of the Holy and Undivided Trinity is kept on Sunday the 30th. We round out the month by praying for the repose of the souls of those who have given their lives in the service of our Nation with a requiem on Memorial Day, May 31st at 8:00 am (not our usual 10:00 time as Fr. -

Feast of Corpus Christi June 6, 2021

FEAST OF CORPUS CHRISTI JUNE 6, 2021 MASS INTENTIONS Sat. 6/5 4:00 PM Peter and Mayme Sefing by the Turri Family Sun. 6/6 11:00 AM Anna and Andy Prokopovich by Michalene and Jim Eisenhart Mon. 6/7 7:00 PM Helen E. Capozzelli by Bob and Lorraine Giulani Tue. 6/8 7:00 AM Mary Woods by Her Son Jim Mellon Wed 6/9 7:00 AM Nancy Hartzel by Sally and Les Thur. 6/10 7:00 AM Thomas Chuckra, Jr. by His Wife Mary Fran Fri. 6/11 7:00 AM Betty Wysocki by JoAnn Heller Sat. 6/12 4:00 PM Deceased Members of Freeland Class of 1966 by Paula Sun. 6/13 11:00AM James P. Cosgrove, Sr. by His Family Weekend of May 15/16: Sunday $3,930.00; Loose $33.00; Dues $2,051.00; Care and Education of Priests $98.00; Initial Offering $10.00; Solemnity of Mary $10.00; Ash Wednesday $5.00; Holy Thursday $5.00; Good Friday $5.00; Easter Flowers $15.00; Easter $40.00; Ascension $378.00; Holy Father $10.00; Home Mission $21.00; Catholic Communications $206.00; Poor Box $86.00 Weekend of May 22/23: Sunday $3,814.00; Loose $307.00; Dues $946.00; Care and Education of Priests $105.00; Feast of the Assumption $5.00; Christmas $5.00; Rice Bowl $5.00; Easter Flowers $20.00; Holy Thursday $5.00; Good Friday $5.00; Easter $20.00; Catholic Home Mission $20.00; Ascension $46.00; Catholic Communications $80.00; Holy Father $10.00; Poor Box $246.57 Weekend of May 29/30: Sunday $2,767.00; Loose $28.00; Dues $836.00; Care and Education of Priests $40.00; Ascension $45.00; Catholic Communications $25.00; Churches in Europe $20.00; Holy Father $10.00; Poor Box $107.17 CANDLES ON THE ALTAR are in Memory of Walter Tamposki by Dan Ravina MEMORIAL DONATIONS in Memory of Joan Staruch: $50.00 by Debbie, Jessica, and Matthew Stivers; $100.00 by Gerald and Mary Feissner and Family. -

Opportunities for Recreation in Pre-Industrial Times

Opportunities for Recreation in Pre-Industrial times The working life of a peasant was long and hard, but there were many holidays: Most holidays were determined by the church holy days. At Christmas there were twelve days of leisure and recreation until the twelfth night, a week at Easter and time off at Whitsun. There were occasional breaks from work – wakes, fairs, mops, market days, weddings, funerals. Depending on the type of holiday, certain entertainments and food were provided by the church or Lord of the Manor. Laws dictated that young men practised their archery but many ignored that and played ball games instead. Gambling was a means of getting rich quick so lots of activities allowed the opportunity for gambling: cock fighting, bare-knuckle boxing, bear-baiting. In the Middle Ages, leisure time was something for the whole community: everyone joined in: the pub was a gathering place for gambling, drinking, courtship, gossip and playing games. Weekly markets allowed people to trade – a meeting place for town and country people: a chance to buy and sell goods – just like modern markets and boot sales ! The village square was transformed on market days: entertainments and leisure activities were laid on: bull baiting, bear baiting, games, contests, rides, cock fighting, smock races for women, jugglers, musicians, puppet shows !! Local Wakes • The churches of small rural towns and villages in Britain all have a foundation (veneration) day, to honour the Patron Saint of the church. These special days became local holidays ‘holydays’, whereby a visit to church was followed by a festival. -

RINGING ROUND DEVON GUILD of DEVONSHIRE RINGERS Newsletter 73: March 2009

RINGING ROUND DEVON GUILD OF DEVONSHIRE RINGERS Newsletter 73: March 2009 EXETER CATHEDRAL BELLS AND RINGERS This year, churches of all denominations across Devon are celebrating 1100 years of the westward expansion of Christianity from the Diocese of Wessex at Sherborne to Devon in 909. Initially, the home of what became the Diocese of Exeter was Crediton, moving to Exeter in 1050. The Cathedral has organized a number of events for the year, the climax of which is a Celebration Day in Exeter on Saturday 27 June. So with the Cathedral as the seat of the Diocese and thus of the celebrations, it seemed appropriate to spotlight the Cathedral bells and ringers. The South Tower Andrew Digby illustrates the size of Grandisson The South Tower contains 14 bells that are hung for full circle change ringing. They are an eclectic mix of weights and ages and constitute the second or third heaviest ring of bells in the world (depending on definition). They are usually rung as a 12, with the two semitones allowing lighter combinations of 8 or 10 to be rung. The tenor, Grandisson is 72½ Cwt in Bb, and the treble is 6 Cwt. The oldest bell in the tower (the 4th) dates from 1616, and the newest (the Jubilee treble) was added in 1977. Several bells have been re-cast over the years; Grandisson itself was last re-cast in 1902. Ringing here is not for the faint-hearted. The bells are heavy and demanding, the ringing chamber is enormous and can seem intimidating, even after several visits, and the huge range of bell weights and sizes means that ropesight is quite a challenge. -

Liturgy Cheat Sheet for Each Team

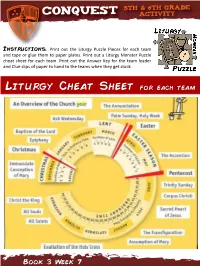

Instructions: Print out the Liturgy Puzzle Pieces for each team and tape or glue them to paper plates. Print out a Liturgy Monster Puzzle cheat sheet for each team. Print out the Answer Key for the team leader and Clue slips of paper to hand to the teams when they get stuck. Liturgy Cheat Sheet for each team Book 3 Week 7 Answer Key for team leader 1. Advent Season 2. Immaculate Conception 3. Christmas 4. Christmas Season 5. Holy Family 6. Mary, Mother of God 7. Epiphany 8. Baptism of the Lord 9. Ordinary Time after Christmas 10.Ash Wednesday 11. Lent 12.Annunciation 13. Palm Sunday 14. Holy Thursday 15. Good Friday 16. Holy Saturday (Easter Vigil) 17. Easter Sunday 18. Easter Season 19. Ascension 20.Pentecost 21.Ordinary Time after Easter 22.Trinity Sunday 23.Corpus Christi 24.Sacred Heart 25.Immaculate Heart 26.Assumption 27.Triumph of the Cross 28.All Saints Day 29.All Souls Day 30.Christ the King Liturgy clues for team leader to hand out Advent Season The Advent Season is the beginning of the Church's liturgical year. The First Sunday of Advent begins four Sundays before Christmas. Immaculate Conception Each year on December 8th, the Church celebrates this feast which honors the fact that Mary was conceived without original sin through the grace of God so that she may be a fitting home for our savior. Christmas Each year on December 25th, the Church celebrates the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ in history. Christmas Season The Christmas Season runs from Christmas day to the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord. -

Thinking Aloud Ix This Monday Is Whit Monday. Many People Will Hardly

Thinking aloud ix This Monday is Whit Monday. Many people will hardly remember it since the Spring Bank Holiday replaced it. Whit Monday was the first Bank Holiday granted in 1871, Christmas Day and Easter Monday were added. This Sunday is Whitsunday, the New Testament reminds us of the help and support given to us by God in His Holy Spirit. It was a very popular day for Baptism when white is traditionally worn, hence Whit or White Sunday. It’s a forward looking festival, God’s support for all we are doing and going to do. Lockdown is being relaxed a little on this Whit Monday, but life remains with a need for caution. We must remember that there are many who are still advised to self-isolate, there are many others who remain cautious for various reasons and will not be rushing out to the shops to buy the latest treat from Birds’. As we look toward to a more normal future it is important we continue to support the elderly and the vulnerable, we maintain our new friendships with neighbours and treasure close relationships with family and friends again. We still need to support in our prayers the NHS and carers and everyone who restlessly works to keep life normal for us. There are still thousands who are bereaved. The message of Whitsun is living with the support of the hand of the Creator God as we remember we are hopefully moving slowly beyond Coronavirus with enhanced compassion, support, and encouragement for all we meet. Last weekend saw another important celebration, that of our Muslim friends, the keeping of Eid.