CROATIAN JOURNAL of PHILOSOPHY Articles an Anscombean Reference for ‘I’? ANDREW BOTTERELL and ROBERT J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kruger Oelof Abraham 2016.Pdf (2.709Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU NATAL A robust air refractometer for accurate compensation of the refractive index of air in everyday use Oelof Abraham Kruger 2016 A robust air refractometer for accurate compensation of the refractive index of air in everyday use Oelof Abraham Kruger 215081719 December 2016 A robust air refractometer for accurate compensation of the refractive index of air in everyday use Oelof Abraham Kruger 215081719 December 2016 Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Physics School of Chemistry and Physics, Discipline of Physics College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal (PMB), Private Bag X01, Scottsville, 3209, South Africa Supervisor: Professor Naven Chetty P a g e | 3 Declaration This thesis describes the work undertaken at the University of KwaZulu-Natal under the supervision of Prof N. Chetty between March 2015 and December 2016. I declare the work reported herein to be own research, unless specifically indicated to the contrary in the text. Signed:……………………………………….. Student: O. A. Kruger On this ……….day of ……………..2016 I hereby certify that this statement is correct. Signed:……………………………………….. Supervisor: Prof N. Chetty On this ……….day of ……………..2016 P a g e | 4 ACKOWLEDGMENTS A heartfelt thank you to my family for coping with all the time I spent away from home for enduring my temperaments when I was home and working on the project. I wish also to thank my supervisor, Naven Chetty who has played a vital role in not only supervising the project, but also my overall guidance and support on all aspects of the projects. -

Metrology Principles for Earth Observation: the NMI View

Metrology Principles for Earth Observation: the NMI view Emma Woolliams 17th October 2017 Interoperability Decadal Stability Radiometric Accuracy • Identical worldwide • Century-long stability • Absolute accuracy Organisation of World Metrology . The Convention of the Metre 1875 (Convention du Mètre) . International System of Units (SI) 1960 (Système International d'Unités) . Mutual Recognition Arrangement (CIPM-MRA) 1999 This presentation 1. How world metrology achieves interoperability, stability and accuracy 2. How these principles can be applied to Earth Observation 3. Resources to help This presentation 1. How world metrology achieves interoperability, stability and accuracy 2. How these principles can be applied to Earth Observation 3. Resources to help • How do we make sure a wing built in one country fits a fuselage built in another? • How do we make sure the SI units are stable over centuries? • How do we improve SI over time without losing interoperability and stability? History of the metre 1795 1799 1960 1983 Metre des Archives 1889 International Distance light Prototype travels in 1/299 792 458th of a second 2018 1 650 763.73 wavelengths of a krypton-86 transition 1 ten millionth of the distance from the • Stable North Pole to the • Improves over time Distance that makes Equator through • Reference to physical process the speed of light Paris 299 792 458 m s-1 Three principles Traceability Uncertainty Analysis Comparison Traceability Unit definition SI Primary At BIPM and NMIs standard Secondary standard Laboratory Users Increasing Increasing uncertainty calibration Industrial / field measurement Traceability: An unbroken chain Transfer standards Audits SI Rigorous Documented uncertainty procedures analysis Rigorous Uncertainty Analysis The Guide to the expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) • The foremost authority and guide to the expression and calculation of uncertainty in measurement science • Written by the BIPM, ISO, etc. -

Overload Journal

Series Title # Placeholder page for an advertisement AUTHOR NAME Bio MMM YYYY ||6{cvu} OVERLOAD CONTENTS OVERLOAD 133 Overload is a publication of the ACCU June 2016 For details of the ACCU, our publications and activities, ISSN 1354-3172 visit the ACCU website: www.accu.org Editor Frances Buontempo [email protected] Advisors Andy Balaam 4 Dogen: The Package Management [email protected] Saga Matthew Jones Marco Craveiro discovers Conan for C++ [email protected] package management. Mikael Kilpeläinen [email protected] Klitos Kyriacou 7 QM Bites – Order Your Includes [email protected] (Twice Over) Steve Love Matthew Wilson suggests a sensible [email protected] ordering for includes. Chris Oldwood [email protected] 8A Lifetime in Python Roger Orr [email protected] Steve Love demonstrates how to use context Anthony Williams managers in Python. [email protected]. uk 12 Deterministic Components for Matthew Wilson [email protected] Distributed Systems Sergey Ignatchenko considers what can Advertising enquiries make programs non-deterministic. [email protected] Printing and distribution 17 Programming Your Own Language in C++ Vassili Kaplan writes a scripting language in C++. Parchment (Oxford) Ltd Cover art and design 24Concepts Lite in Practice Pete Goodliffe Roger Orr gives a practical example of the use of [email protected] concepts. Copy deadlines All articles intended for publication 31 Afterwood in Overload 134 should be Chris Oldwood hijacks the last page for an submitted by 1st July 2016 and those for Overload 135 by ‘A f t e r w o o d ’. 1st September 2016. The ACCU Copyrights and Trade Marks The ACCU is an organisation of Some articles and other contributions use terms that are either registered trade marks or claimed programmers who care about as such. -

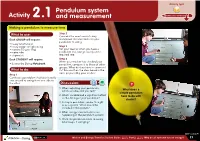

Science by Doing Rock Paper Scissors Student Guide

Activity type Pendulum system Activity 2.1 and measurement DOWNLOAD e-NOTEBOOK Making a pendulum to measure time What to use: Step 2 Consider the most accurate way Each GROUP will require: to measure the time taken for your pendulum to swing. • heavy retort stand • heavy cotton or light string Step 3 • masses (50 g to 1 kg) Tell your teacher when you have a • metre ruler pendulum that swings exactly at the • stopwatch. required rate. Each STUDENT will require: Step 4 When your teacher has checked your • Science by Doing Notebook. pendulum, compare it to those of other groups. What do they have in common? What to do: Put this result on the class board in the table prepared by your teacher. Step 1 Construct a pendulum that takes exactly one second to swing from one side to the other. Discussion: ? 1. When adjusting your pendulum, What does a which variables did you test? simple pendulum 2. Which variable had a significant effect have to do with on the timing of your pendulum? clocks? 3. A simple pendulum can be thought of as a system. What should be included in this system? 4. What energy transformations are happening in the pendulum system? 5. Once the pendulum starts to swing, what keeps it swinging? Motion and Energy Transfer Student GuideMotion andPart Energy2 Transfer Why do Student all systems Guide run on energy? Part 2 17 Activity 2.1 Pendulum system and measurement Continued Our metric system of measurement is often referred to as the SI system. This ? Acomes HISTORY from theOF SystémeTHE METRE International, adopted in the French revolution What does a simple during the 1790s. -

Speed of Light

Speed of light From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted c, is a universal physical constant important in many areas of physics. Its precise value is 299792458 metres per second (approximately 3.00×108 m/s), since the length of the metre is defined from this constant and the international standard for time.[1] According to special relativity, c is the maximum speed at which all matter and information in the universe can travel. It is the speed at which all massless particles and changes of the associated fields (including electromagnetic radiation such as light and gravitational waves) travel in vacuum. Such particles and waves travel at c regardless of the motion of the source or the inertial reference frame of the observer. In the theory of relativity, c interrelates space and time, and also appears in the famous equation of mass–energy equivalence E = mc2.[2] Speed of light Sunlight takes about 8 minutes 17 seconds to travel the average distance from the surface of the Sun to the Earth. Exact values metres per second 299792458 Planck length per Planck time 1 (i.e., Planck units) Approximate values (to three significant digits) kilometres per hour 1080 million (1.08×109) miles per second 186000 miles per hour 671 million (6.71×108) Approximate light signal travel times Distance Time one foot 1.0 ns one metre 3.3 ns from geostationary orbit to Earth 119 ms the length of Earth's equator 134 ms from Moon to Earth 1.3 s from Sun to Earth (1 AU) 8.3 min one light year 1.0 year one parsec 3.26 years from nearest star to Sun (1.3 pc) 4.2 years from the nearest galaxy (the Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy) to 25000 years Earth across the Milky Way 100000 years from the Andromeda Galaxy to 2.5 million years Earth from Earth to the edge of the 46.5 billion years observable universe The speed at which light propagates through transparent materials, such as glass or air, is less than c; similarly, the speed of radio waves in wire cables is slower than c. -

Essence of the Metric System

Outline of the metric system - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outline_of_the_metric_system From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the metric system: Metric system – various loosely related systems of measurement that trace their origin to the decimal system of measurement introduced in France during the French Revolution. 1 Nature of the metric system 2 Metric units of measure 3 History of the metric system 4 Politics of the metric system 5 Future of the metric system 6 Metric system organizations 7 Metric system publications 8 Persons influential in the metric system 9 See also "The metric system is for all people for all 10 References time." (Condorcet 1791) Four objects used in 11 External links making measurements in everyday situations that have metric calibrations are shown: a tape measure calibrated in centimetres, a thermometer calibrated in degrees Celsius, a kilogram mass, and an electrical multimeter The metric system can be described as all of the following: which measures volts, amps and ohms. System – set of interacting or interdependent components forming an integrated whole. System of measurement – set of units which can be used to specify anything which can be measured. Historically, systems of measurement were initially defined and regulated to support trade and internal commerce. Units were arbitrarily defined by fiat (see statutory law) by the ruling entities and were not necessarily well inter-related or self-consistent. When later analyzed and scientifically, some quantities were designated as fundamental units, meaning all other needed units of measure could be derived from them. -

ELASTIC DESIGN Tools for Alternative Understandings Bettina

ELASTIC DESIGN Tools for Alternative Understandings Bettina Marianne Bruder Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art & Design, The University of New South Wales April 2017 DECLARATIONS Originality Statement ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed: Date: 24.04.2017 Authenticity Statement ‘I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor variations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.’ Signed: Date: 24.04.2017 ii Copyright Statement ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

From Foot to Metre, from Marc to Kilo

From foot to metre, from marc to kilo The history of weights and measures illustrated by objects in the collections of the Musée d’histoire des sciences From foot to metre This booklet gives a brief account of a key chapter in the development of metrology : the transformation from traditional units of length and weight to the metric system. It presents some instruments made in Geneva which played an important role in metrology : rulers, dividing engines, measuring machines, etc. Conversion table of new units of measurement Téron, Instruction sur le système de mesures et poids uniformes pour toute la République française, Genève, 1802 Library of the Musée d’histoire des sciences Cover : Circle dividing engine Deleuil laboratory precision scales SIP, Instruments de physique et de mécanique, Genève, 1903 Syndicat des constructeurs en instruments d’optique et de précision, Library of the Musée d’histoire des sciences L’industrie française des instruments de précision, Paris 1980 Library of the Musée d’histoire des sciences 1 The foot One of the oldest units of measurement Before the introduction of the metre during the French Revolution, units of length were based on parts of the human body. One of the oldest is the Nippur cubit 51.85 cm long used in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC. Later, Egyptian surveyors divided the cubit into 28 equal parts or digits. Sixteen digits yielded a new unit, the foot, 29.633 cm in length which was later adopted by the Romans. During the Middle Ages, a new foot measurement appeared derived more or less directly from the Romans. -

Not Exactly (Draft. Please Do Not Quote)

1 Not Exactly in Praise of Vagueness by Kees van Deemter University of Aberdeen (Draft. Please do not quote) 2 Preface Vagueness is the topic of quite a few scholarly books for professional linguists, philosophers and computer scientists. This book targets a much broader au- dience. For this reason, I have kept the exposition as informal as possible, focussing on the essence of an idea rather than its technical incarnation in formulas or computer programs. In a few cases where there is substantial con- troversy about the right approach to a problem, I have used fictional dialogues – a tried and tested method since Plato’s days of course – to give readers a sense of the issues. Although some things have been too complex to yield willingly to this informal treatment, it has been a delight to discover how much complex material can be reduced to simple ideas. On a good day, it even seems to me that there are themes that are best explored in this informal way. The fact that the book is informal does not necessarily make it an easy read. For one thing, it requires a certain philosophical spirit, in which one asks why certain well-known facts hold. Moreover, we will not be content when we, sort of, dimly understand why something happens: in many cases we will ask how this understanding can be given a place in a known model or theory (such as Symbolic Logic or Game Theory). Essentially this means that we will insist on understanding vagueness in a way that is compatible with everything else we know about the world. -

The Cape Geodetic Standards and Their Impact on Africa

The Cape Geodetic Standards and Their Impact on Africa Tomasz ZAKIEWICZ, South Africa Key words: standards, length measure, metre, Cape foot, 30th Meridian, baseline, ellipsoid. SUMMARY The Cape Geodetic Standards consist of two ten-foot iron bars, brought from England in 1839, and used by Sir Thomas Maclear, during the years 1841/42, for the verification of Lacaille’s Arc of 1752. Forty years later, when Sir David Gill, having commenced the Geodetic Survey of South Africa, initiated the measurement of the Arc of the 30th Meridian, the “Cape Bar A” was still in existence and kept as a standard reference. In 1886, in Paris, the bar was standardized in terms of the international metre. However, due to the implications with the legal and international metres, it appeared later, that the results of the geodetic triangulation were computed not in English feet but in terms of the fictitious unit now called the South African Geodetic foot. This caused the reference ellipsoid to be renamed to the Modified Clarke 1880 ellipsoid. Later, as a consequence of an extension of the Cape Datum, the 1950 ARC Datum was established, giving a uniform framework of triangulation from the Cape to the Equator. Until the present, some countries, along the 30th Meridian, use the 1950 ARC Datum, thus, the Modified 1880 Clarke ellipsoid, or, its revision, the Arc 1960. The paper gives an outline of the development of the English and metric systems, which have, without doubt, influenced the establishment of the “commercial” Cape units, used for everyday purposes, and, also, of the unit of the Geodetic Survey of South Africa. -

OPEN HOUSE Visitor Guide

OPEN HOUSE Visitor Guide Thursday 17 May 2018 from 2 pm to 8 pm Welcome to the National Physical Laboratory The Measure of All Things We are delighted to welcome you to the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) and show you our world-class laboratories as well as giving you an insight into the amazing science that we do here. NPL is the UK’s National Measurement Institute. We’re responsible for making sure that all measurements made in the UK can be traced back to agreed standards, ensuring consistency and reliability. Accurate measurements are important in so many fields; our research helps support scientific and commercial innovation, international trade, environmental protection, and health and wellbeing. Measurement expertise is relevant to global challenges, such as climate change, curing diseases and supporting the latest communications technology. Our role in supporting trade, which we have been doing since 1902, has probably never been as important as we head towards exiting the EU. Last year we re-launched NPL to align more closely with government priorities and industry needs. We are focused on advanced manufacturing, digital, energy and environment, and life sciences and health. We are dedicated to creating impact from science, engineering and technology, and making a real difference to companies and individuals. Our renewed focus will help accelerate UK industry for the next 100 years and beyond. Our Open House coincides with World Metrology Day (metrology is the science of measurement), which falls on 20 May, and is particularly important this year. We are celebrating NPL’s leading role in the international programme to review the standard units of measurements. -

Draft. Please Do Not Quote) 2 Preface

1 Not Exactly in Praise of Vagueness by Kees van Deemter University of Aberdeen (Draft. Please do not quote) 2 Preface Vagueness is the topic of quite a few scholarly books for professional academics. This book targets a much broader audience. For this reason, the exposition has been kept as informal as possible, focussing on the essence of an idea rather than its technical incarnation in formulas or computer programs. Most chapters of the book (with the exception of chapters 8 and 9, which rely on the material explained in earlier chapters) are self-explanatory. In a few areas of substantial controversy, I have used fictional dialogues – a tried and tested method since Plato’s days of course – to give readers a sense of the issues. Although some things have been too complex to yield willingly to this treatment, it has been a delight to discover how much complex material can be reduced to simple ideas. On a good day, it even seems to me that there are themes that are best explored in this informal way, free from the constraints of an academic straightjacket. The fact that the book is informal may not always make it an easy read. For one thing, it requires a somewhat philosophical spirit, in which one asks why certain well-known facts hold. Moreover, we will not be content when we, sort of, dimly understand why something happens: we will ask how this understanding can be given a place in a known theory. Essentially this means that we will insist on trying to understand vagueness in a way that is compatible with everything else we know about the world.