Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development and Counter-Intervention Efforts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK

Occasional Paper No. 2 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. Monitoring Proliferation Threats Project MONTEREY INSTITUTE CENTER FOR NONPROLIFERATION STUDIES OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES THE CENTER FOR NONPROLIFERATION STUDIES The Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Monterey Institute of International Studies (MIIS) is the largest non-governmental organization in the United States devoted exclusively to research and training on nonproliferation issues. Dr. William C. Potter is the director of CNS, which has a staff of more than 50 full- time personnel and 65 student research assistants, with offices in Monterey, CA; Washington, DC; and Almaty, Kazakhstan. The mission of CNS is to combat the spread of weapons of mass destruction by training the next generation of nonproliferation specialists and disseminating timely information and analysis. For more information on the projects and publications of CNS, contact: Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute of International Studies 425 Van Buren Street Monterey, California 93940 USA Tel: 831.647.4154 Fax: 831.647.3519 E-mail: [email protected] Internet Web Site: http://cns.miis.edu CNS Publications Staff Editor Jeffrey W. Knopf Managing Editor Sarah J. Diehl Copyright © Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., 1999. OCCASIONAL PAPERS AVAILABLE FROM CNS: No. 1 Former Soviet Biological Weapons Facilities in Kazakhstan: Past, Present, and Future, by Gulbarshyn Bozheyeva, Yerlan Kunakbayev, and Dastan Yeleukenov, June 1999 No. 2 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK, by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., November 1999 No. 3 Nonproliferation Regimes at Risk, Michael Barletta and Amy Sands, eds., November 1999 Please contact: Managing Editor Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute of International Studies 425 Van Buren Street Monterey, California 93940 USA Tel: 831.647.3596 Fax: 831.647.6534 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK [Note: Page numbers given do not correctly match pages in this PDF version.] Contents Foreword ii by Timothy V. -

Phillip Saunders Testimony

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China’s Nucle ar Force s June 10, 2021 Phillip C. Saunders Director, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute of National Strategic Studies, National Defense University The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Introduction The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is in the midst of an ambitious strategic modernization that will transform its nuclear arsenal from a limited ground-based nuclear force intended to provide an assured second strike after a nuclear attack into a much larger, technologically advanced, and diverse nuclear triad that will provide PRC leaders with new strategic options. China also fields an increasing number of dual-capable medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles whose status within a future regional crisis or conflict may be unclear, potentially casting a nuclear shadow over U.S. and allied military operations. In addition to more accurate and more survivable delivery systems, this modernization includes improvements to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) and strategic intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems that will provide PRC leaders with greater situational awareness in a crisis or conflict. These systems will also support development of ballistic missile defenses (BMD) and enable possible shifts in PRC nuclear -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

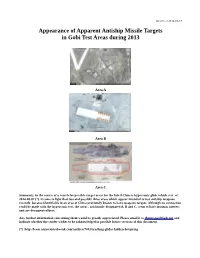

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

INDO-PACIFIC China’S New Road-Mobile ICBM DF-41 Officially Unveiled

INDO-PACIFIC China’s New Road-Mobile ICBM DF-41 Officially Unveiled OE Watch Commentary: On 1 October, China held a large military parade in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. The Chinese military used the occasion to show off a number of pieces of new equipment, including a new road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the DF-41. According to the accompanying article, the DF- 41 is a “mainstay of China’s…nuclear deterrent.” While China maintains a small number of silo-based DF-5 ICBMs, it has historically pursued mobile launch systems for its ballistic missiles to improve their survivability in a conflict. Adoption of an off- road-capable transporter-erector-launcher (TEL) gives the missile a much greater range of launch and concealment positions. Separate Chinese media reporting on the DF-41 noted that the missile has a range of 14,000 and can carry up to ten independently targetable nuclear warheads. However, there is a compromise between distance and “throw weight”—the number of warheads and penetration aids (decoys) that a missile Chinese Mobile ICBMs. can carry—and the missile likely carries considerably Image by Peter Wood fewer when fired to maximum range. Researchers using commercial imagery previously identified what appears to be a nuclear silo for the DF-41, likely used as part of testing the missile. Reporting in China Daily in 2017 claimed that it could be launched from trains and silos as well as the road-mobile configuration. The DF-41 was accompanied by 16 DF-31AG missiles, an improved version of the DF-31 mobile ICBM. -

Able Archers: Taiwan Defense Strategy in an Age of Precision Strike

(Image Source: Wired.co.uk) Able Archers Taiwan Defense Strategy in an Age of Precision Strike IAN EASTON September 2014 |Able Archers: Taiwan Defense Strategy and Precision Strike | Draft for Comment Able Archers: Taiwan Defense Strategy in an Age of Precision Strike September 2014 About the Project 2049 Institute The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s Cover Image Source: Wired.co.uk mid-point. Located in Arlington, Virginia, the organization fills a gap in the public policy realm Above Image: Chung Shyang UAV at Taiwan’s 2007 National Day Parade through forward-looking, region-specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its Above Image Source: Wikimedia interdisciplin ary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. ii |Able Archers: Taiwan Defense Strategy and Precision Strike | Draft for Comment About the Author Ian Easton is a research fellow at the Project 2049 Institute, where he studies defense and security issues in Asia. During the summer of 2013 , he was a visiting fellow at the Japan Institute for International Affairs (JIIA) in Tokyo. Previously, he worked as a China analyst at the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA). He lived in Taipei from 2005 to 2010. During his time in Taiwan he worked as a translator for Island Technologies Inc. and the Foundation for Asia-Pacific Peace Studies. He also conducted research with the Asia Bureau Chief of Defense News. -

China Missile Chronology

China Missile Chronology Last update: June 2012 2012 18 May 2012 The Department of Defense releases the 2012 “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China” report. The report highlights that the PLA Air force is modernizing its ground‐based air defense forces with conventional medium‐range ballistic missiles, which can “conduct precision strikes against land targets and naval ships, including aircraft carriers, operating far from China’s shores beyond the first island chain.” According to the Department of Defense’s report, China will acquire DF‐31A intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and enhanced, silo‐based DF‐5 (CSS‐4) ICMBs by 2015. To date, China is the third country that has developed a stealth combat aircraft, after the U.S. and Russia. J‐20 is expected conduct military missions by 2018. It will be equipped with “air‐to‐air missiles, air‐to‐surface missiles, anti‐radiation missiles, laser‐guided bombs and drop bombs.”J‐20 stealth fighter is a distinguished example of Chinese military modernization. – Office of Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2012,” distributed by U.S. Department of Defense, May 2012, www.defense.gov; Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, David Helvey, “Press Briefing on 2012 DOD Report to Congress on ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,’” distributed by U.S. Department of Defense, 18 May 2012, www.defense.gov; “Chengdu J‐20 Multirole Stealth Fighter Aircraft, China,” Airforce‐Technology, www.airforce‐technology.com. 15 April 2012 North Korea shows off a potential new ICBM in a military parade. -

The Future of the U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. C O R P O R A T I O N The Future of the U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force Lauren Caston, Robert S. -

Chinabrief Volume X Issue 8 April 16, 2010

ChinaBrief Volume X Issue 8 April 16, 2010 VOLUME X ISSUE 8 APRIL 16, 2010 IN THIS ISSUE: IN A FORTNIGHT By L.C. Russell Hsiao 1 SYRIA IN CHINA’S NEW SILK ROAD STRATEGY By Christina Y. Lin 3 KARZAI’S STATE VISIT HIGHLIGHTS BEIJING’S AFGHAN PRIORITIES By Richard Weitz 5 TAIWAN’S NAVY: ABLE TO DENY COMMAND OF THE SEA? By James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara 8 CHINESE DEFENSE EXPENDITURES: IMPLICATIONS FOR NAVAL MODERNIZATION By Andrew S. Erickson 11 Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan China Brief is a bi-weekly jour- In a Fortnight nal of information and analysis covering Greater China in Eur- asia. IMPLICATIONS OF KYRGYZSTAN REVOLT ON CHINA’S XINJIANG POLICY By L.C. Russell Hsiao China Brief is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation, a s the political crisis in Kyrgyzstan reaches a turning point, after opposition forces private non-profit organization Aseized the capital Bishkek in a bloody clash and ousted the president and his based in Washington D.C. and allies, Chinese leaders from regions across China have reportedly descended upon is edited by L.C. Russell Hsiao. Xinjiang en masse in a rare spectacle that carried with it a heavy political undertone. The sight of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders at the top provincial party- The opinions expressed in secretary level arriving in droves in Xinjiang appears to highlight the importance that China Brief are solely those of the authors, and do not the Chinese leadership attaches to the future of this restive northwestern region in necessarily reflect the views of the People’s Republic that still hangs uncertainly against the backdrop of the violent The Jamestown Foundation.