Detail of the Ishtar-Gate (A Reconstruction of the Babylonian Gate in Berlin’S Pergamon Museum): 2 Showing a Lion, Symbol of the Goddess Ishtar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Glass for the Pharaoh Thilo Rehren

. ARCHAEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL HildO<heim, Genn•ny) '' excmting '� Red glass for the Pharaoh industrial estate dating to the foundatio period of the new city, including the larg-� I Thilo Rehren est known bronze foundries of antiquity,1 Glass in ancient Egypt appears to have been used as a substitute military workshops supplying and main for precious stones that were not available in the country. Here taining the pharaoh's chariotry including the process of glass manufacture is traced through the examina stables for hundreds of horses, and the only known production site for glass in tion of the fr agmentaryremains of ceramic reaction vessels and Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia. The crucibles used in the production of small glass ingots. excavations date back to the 1980s, but only in the past couple of years have we been able to identify the glassmaking evi n archaeological terms, glass is a these precious materials, and ancient Egypt dence, although much of it had been exca relatively young material that was is no exception to this rule. It was famous vated many years previously. Why this invented much later than pottery or for its riches in gold, but had no silver ores; delay? Because we didn't know how to rec Imetals; only from the beginning of it produced amethyst, carnelian and tur ognize glassmaking: there being no prece the Late Bronze Age onwards do we quoise, but not lapis lazuli, amber or ob dent or template to follow when looking have good evidence for its intentional and sidian. Should the country's rulers there for Bronze Age glassmaking, and the evi routine production. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Money, History and Energy Accounting Essay Author: Skip Sievert June 2008 Open Source Information

Some Historic aspects of money... Money, History and Energy accounting Essay author: Skip Sievert June 2008 open source information. The Technocracy Technate design uses Energy accounting as the viable alternative to the current Price System. Energy Accounting- Fezer. The Emergence of money The use of barter like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago. To organize production and to distribute goods and services among their populations, pre- market economies relied on tradition, top-down command, or community cooperation. Relations of reciprocity and/or redistribution substituted for market exchange. Trading in red ochre is attested in Swaziland. Shell jewellery in the form of strung beads also dates back to this period and had the basic attributes needed of commodity money. In cultures where metal working was unknown... shell or ivory jewellery was the most divisible, easily stored and transportable, relatively scarce, and impossible to counterfeit type of object that could be made into a coveted stylized ornament or trading object. It is highly unlikely that there were formal markets in 100,000 B.P. Nevertheless... something akin to our currently used concept of money was useful in frequent transactions of hunter-gatherer cultures, possibly for such things as bride purchase, prostitution, splitting possessions upon death, tribute, obtaining otherwise scarce objects or material, inter-tribal trade in hunting ground rights.. and acquiring handcrafted implements. All of these transactions suffer from some basic problems of barter — they require an improbable coincidence of wants or events. History of the beginnings of our current system Sumerian shell money below. Sumer was a collection of city states around the Lower Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now southern Iraq. -

A Critical Analysis of the Legal and Quasi-Legal Recognition of the Underlying Principles and Norms of Cultural Heritage

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE LEGAL AND QUASI-LEGAL RECOGNITION OF THE UNDERLYING PRINCIPLES AND NORMS OF CULTURAL HERITAGE Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Charlotte Cassandra Woodhead LL.M Department of Law University of Leicester 2014 Charlotte Woodhead A critical analysis of the legal and quasi-legal recognition of the underlying principles and norms of cultural heritage Certain things, places and practices are valuable to particular individuals, communities, nations or to mankind to such a degree that the loss or destruction would be a misfortune to the culture, identity, heritage or religious practices of those people(s). For the purposes of this thesis, cultural heritage represents the intangible aspect of these important things, places and practices. It will be argued that despite the existence of various cultural heritage principles which represent the different types of value, public legacy and associated norms with its subject matter, these principles are not always effectively upheld in the governing legal regime, although a body of principles akin to legal ones has developed, from professional practice, codes of ethics and non-legal decision-making bodies. Recent legal intervention has responded to political imperatives at the risk of a clear and consistent regime to effectively meet the underlying principles of cultural heritage. The most effective means of fulfilling these principles and norms is by treating cultural heritage as an intangible legal concept, akin to property which in its English common law form is really a bundle of rights associated with things tangible or intangible rather than simply ownership and possession or the physical things themselves. -

Copyright by Amy Beth Angell 2017

Copyright by Amy Beth Angell 2017 The Thesis committee for Amy Beth Angell Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Images of Divinities in Functional Objects: A Study of Seventh-Century BCE Perirrhanteria in Greek Sanctuary Contexts APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: __________________________________________ Athanasio (Nassos) Papalexandrou, Supervisor _________________________________________ Penelope Davies Images of Divinities in Functional Objects: A Study of Seventh-Century BCE Perirrhanteria in Greek Sanctuary Contexts by Amy Beth Angell, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Abstract Images of Divinities in Functional Objects: A Study of Seventh-Century BCE Perirrhanteria in Greek Sanctuary Contexts Amy Beth Angell, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Athanasio (Nassos) Papalexandrou Perirrhanteria in Greek sanctuaries are described in general terms as water basins for the purpose of purification. From the mid-seventh century to the early sixth century BCE, the perirrhanteria were made of marble, featured sculptural figures in the place of columnar stands, and found wide distribution among a variety of Greek sanctuaries. Due to the striking motif of the figurative stands, three or four female figures flanked by lions or standing on their backs, scholarship regarding the stone perirrhanteria has been centered on iconography and early monumental sculpture. Although preceding sculptural analyses provide useful information for the history of a motif, the relatively short lifespan of this particular basin type and its appearance in sanctuaries dedicated to an array of deities begs further study of its function in context. -

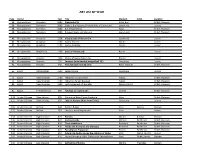

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

Women in the Ancient Near East: a Sourcebook

WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Women in the Ancient Near East provides a collection of primary sources that further our understanding of women from Mesopotamian and Near Eastern civiliza- tions, from the earliest historical and literary texts in the third millennium BC to the end of Mesopotamian political autonomy in the sixth century BC. This book is a valuable resource for historians of the Near East and for those studying women in the ancient world. It moves beyond simply identifying women in the Near East to attempting to place them in historical and literary context, follow- ing the latest research. A number of literary genres are represented, including myths and epics, proverbs, medical texts, law collections, letters and treaties, as well as building, dedicatory, and funerary inscriptions. Mark W. Chavalas is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, where he has taught since 1989. Among his publications are the edited Emar: The History, Religion, and Culture of a Syrian Town in the Late Bronze Age (1996), Mesopotamia and the Bible (2002), and The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation (2006), and he has had research fellowships at Yale, Harvard, Cornell, Cal-Berkeley, and a number of other universities. He has nine seasons of exca- vation at various Bronze Age sites in Syria, including Tell Ashara/Terqa and Tell Mozan/Urkesh. ROUTLEDGE SOURCEBOOKS FOR THE ANCIENT WORLD HISTORIANS OF ANCIENT ROME, THIRD EDITION Ronald Mellor TRIALS FROM CLASSICAL ATHENS, SECOND EDITION Christopher Carey ANCIENT GREECE, THIRD EDITION Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland READINGS IN LATE ANTIQUITY, SECOND EDITION Michael Maas GREEK AND ROMAN EDUCATION Mark Joyal, J.C. -

Reflective Index Reference Chart

REFLECTIVE INDEX REFERENCE CHART FOR PRESIDIUM DUO TESTER (PDT) Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Fluorite 16 - 18 1.434 - 1.434 Emerald 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Corundum 34 - 43 1.762 - 1.770 Opal 17 - 19 1.450 - 1.450 Verdite 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Idocrase 35 - 39 1.713 - 1.718 ? Glass 17 - 54 1.440 - 1.900 Brazilianite 27 - 32 1.602 - 1.621 Spinel 36 - 39 1.718 - 1.718 How does your Presidium tester Plastic 18 - 38 1.460 - 1.700 Rhodochrosite 27 - 48 1.597 - 1.817 TL Grossularite Garnet 36 - 40 1.720 - 1.720 Sodalite 19 - 21 1.483 - 1.483 Actinolite 28 - 33 1.614 - 1.642 Kyanite 36 - 41 1.716 - 1.731 work to get R.I. values? Lapis-lazuli 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Nephrite 28 - 33 1.606 - 1.632 Rhodonite 37 - 41 1.730 - 1.740 Reflective indices developed by Presidium can Moldavite 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Turquoise 28 - 34 1.610 - 1.650 TP Grossularite Garnet (Hessonite) 37 - 41 1.740 - 1.740 be matched in this table to the corresponding Obsidian 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Topaz (Blue, White) 29 - 32 1.619 - 1.627 Chrysoberyl (Alexandrite) 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.755 common Refractive Index values to get the Calcite 20 - 35 1.486 - 1.658 Danburite 29 - 33 1.630 - 1.636 Pyrope Garnet 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.746 R.I value of the gemstone. -

Jiroft” Chlorite Artefacts

IranicaAntiqua, vol. L, 2015 doi: 10.2143/IA.50.0.3053516 SEARCHING FOR MYTHOLOGICAL THEMES ON THE “JIROFT” CHLORITE ARTEFACTS BY Massimo VIDALE (University of Padua, Italy) Abstract: New evidence gathered at the plundered cemetery of Mahtoutabad, near the early urban compound of Konar Sandal South (Jiroft) confirms that here chlorite artifacts were used in elite funerals at the beginning of the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Some carved chlorite vessels from the Jiroft area and Shahdad represent a destructive flood, ending when a divinity lifts a rainbow in the sky. These images are compared with Old Babylonian and later cuneiform versions of flood myths. The paper also singles out indirect analogies with the flood narrative in Genesis 9, 12-17. Then it considers other images of fight between eagles and snakes, as possibly linked with parts of the famous and much discussed Mesopotamian poem of Etana (as already proposed in the past by Youssef Madjidzadeh). In spite of substantial divergences and discontinuities, at least in a crucial case the match between images and selected passages of the ancient sources appears more literal than previously suspected. It is argued that such similarities depended upon the wide circulation and sharing in the Middle and South Asia of the 3rd millennium BCE of codified oral versions of similar legendary themes (in form of narratives, through songs and rhymes). The Halil Rud stone carvers may have translated such intangible vanished heritage through standardized, formal images, in the context of a growing cultural and political interaction between the royal courts of Mesopotamia and those of the eastern pol- ity of Marhashi. -

The Quest for Order O Mesopotamia: “The Land Between the Rivers”

A wall relief from an Assyrian palace of the eighth century B.C.E. depicts Gilgamesh as a heroic figure holding a lion. Page 25 • The Quest for Order o Mesopotamia: “The Land between the Rivers” o The Course of Empire o The Later Mesopotamian Empires • The Formation of a Complex Society and Sophisticated Cultural Traditions o Economic Specialization and Trade o The Emergence of a Stratified Patriarchal Society o The Development of Written Cultural Traditions • The Broader Influence of Mesopotamian Society o Hebrews, Israelites, and Jews o The Phoenicians • The Indo-European Migrations o Indo-European Origins o Indo-European Expansion and Its Effects o EYEWITNESS: Gilgamesh: The Man and the Myth B y far the best-known individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C.E.—for a period of 126 years, according to one semilegendary source—and he led his community in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. Historical sources record little additional detail about Gilgamesh's life and deeds. But Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as history. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as theEpic of Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a perfect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage.