University of Groningen Risk Factors, Endothelial Function, and Clinical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jasn2512editorial 2679..2687

EDITORIALS www.jasn.org UP FRONT MATTERS Despite their common source of angiotensinogen, circu- Renal Angiotensin-Converting lating and renal Ang II production do not always run in Enzyme Upregulation: A parallel. For instance, in patients with diabetes, plasma reninislow,andyettheir renalplasmaflow response to RAS Prerequisite for Nitric Oxide blockade is greatly enhanced, suggesting an overactive Synthase Inhibition–Induced intrarenal RAS.8 The opposite occurs after treatment with very high doses of a renin inhibitor.9 RAS blockers, by interfering Hypertension? with the negative feedback loop between Ang II and renin release, normally upregulate renin synthesis. Particularly † † Lodi C.W. Roksnoer,* Ewout J. Hoorn, and after high doses this upregulation may be .100-fold.9 Re- A.H. Jan Danser* nin inhibitors selectively accumulate in renal tissue, and, *Division of Pharmacology and Vascular Medicine and †Division of therefore, after stopping treatment,10 renal RAS suppres- Nephrology and Transplantation, Department of Internal Medicine, sion will continue, so that renin release stays high. At the Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands same time the inhibitor starts to disappear from plasma, J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2679–2681, 2014. and thus insufficient renin inhibitor is around to block all doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014060549 renin molecules that continue to be released. As a conse- quence, plasma renin activity will increase, and extrarenal Ang II and aldosterone levels may even rise to levels above Angiotensin II (Ang II) production at tissue sites is well baseline.9 established. Interference with such local generation, rather The hypertension occurring in animals during inhibition than with Ang II generation in the circulation, is believed to of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) with L-NG-nitroarginine underlie the beneficial cardiovascular and renal effects of methyl ester (L-NAME) is also believed to involve a discrep- renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers. -

Effect of Aldosterone Breakthrough on Albuminuria During Treatment with a Direct Renin Inhibitor and Combined Effect with a Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist

Hypertension Research (2013) 36, 879–884 & 2013 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/13 www.nature.com/hr ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of aldosterone breakthrough on albuminuria during treatment with a direct renin inhibitor and combined effect with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist Atsuhisa Sato and Seiichi Fukuda We have reported observing aldosterone breakthrough in the course of relatively long-term treatment with renin–angiotensin (RA) system inhibitors, where the plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) increased following an initial decrease. Aldosterone breakthrough has the potential to eliminate the organ-protective effects of RA system inhibitors. We therefore conducted a study in essential hypertensive patients to determine whether aldosterone breakthrough occurred during treatment with the direct renin inhibitor (DRI) aliskiren and to ascertain its clinical significance. The study included 40 essential hypertensive patients (18 men and 22 women) who had been treated for 12 months with aliskiren. Aliskiren significantly decreased blood pressure and plasma renin activity (PRA). The PAC was also decreased significantly at 3 and 6 months; however, the significant difference disappeared after 12 months. Aldosterone breakthrough was observed in 22 of the subjects (55%). Urinary albumin excretion differed depending on whether breakthrough occurred. For the subjects in whom aldosterone breakthrough was observed, eplerenone was added. A significant decrease in urinary albumin excretion was observed after 1 month, independent of changes in blood pressure. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that aldosterone breakthrough occurs in some patients undergoing DRI therapy. Aldosterone breakthrough affects the drug’s ability to improve urinary albumin excretion, and combining a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist with the DRI may be useful for decreasing urinary albumin excretion. -

Guidance on Format of the RMP in the EU in Integrated Format

Splendris Pharmaceuticals GmbH Benazeprilhydrochloride “Splendris” RMP v. 1.0 02 October 2017 VI.2 Elements for a Public Summary VI.2.1 Overview of disease epidemiology Hypertension, is a long term medical condition in which the blood pressure is persistently elevated. Usually it does not cause symptoms, but it is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, and chronic kidney disease. It is the most important preventable risk factor for premature death worldwide. Hypertension results from a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors like rising age, high salt intake, lack of exercise, obesity, or depression. As mechanisms the most evident are disturbance in the kidneys’ salt and water handling and/or abnormalities of the sympathic nervous system. Approximately one billion adults worldwide are affected. In Europe hypertension occurs in 30-43% of adult people, 1 to 5% of children and adolescents and 0.2 to 3% of newborns. Treatment options include changes in lifestyle, like dietary changes, physical exercise, weight loss, and medications, like ACE-inhibitors or calcium channel blockers. VI.2.2 Summary of treatment benefits The benazepril formulation described is a generic equivalent to the innovator formulation. Clinical studies have been performed with benazepril in hypertensive patients showing that blood pressure is significantly reduced. When given with other blood lowering agents e.g. betablockers, the antihypertensive effect is greater than for benazepril alone. In different studies, it has been shown that benazepril was similar or superior in lowering blood pressure and reducing proteinuria or myocardial ischaemia when compared with hydrochlorthiazide, metoprolol, captopril, nifedipine or nitrendipine. -

Apple Health Preferred Drug List (PDL) Updates

Apple Health Preferred Drug List (PDL) Updates The Health Care Authority (HCA) implemented the Apple Health Preferred Drug List (PDL) on January 1, 2018. All managed care plans and the fee-for-service program serving Apple Health clients use this PDL. The PDL now includes over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and many other outpatient drugs. There are now 441 therapeutic drug classes included in the PDL. Updates are ongoing. See which drugs are preferred and whether they require a PA: https://www.hca.wa.gov/billers-providers-partners/programs-and-services/apple-health-preferred- drug-list-pdl. HCA has created policies that document the coverage criteria for drug classes or individual drugs. To view the policies visit: https://www.hca.wa.gov/billers-providers-partners/programs-and- services/apple-health-medicaid-drug-coverage-criteria The drugs within a chosen therapeutic class are evaluated by the HCA Pharmacy and Therapeutic (P&T) Committee/Drug Utilization Review (DUR) Board. The HCA P&T Committee / DUR Board meet at least quarterly. All meetings are open to the public. You can read more about the meetings here: https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/prescription-drug-program/meetings-and-materials Upcoming meeting dates are below: April 21, 2021 June 16, 2021 August 18, 2021 October 20, 2021 December 15, 2021 Current drug classes are listed below: ADHD / ANTI-NARCOLEPSY : DOPAMINE AND NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (DNRIS) ADHD / ANTI-NARCOLEPSY : HISTAMINE H3-RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST / INVERSE AGONIST ADHD / ANTI-NARCOLEPSY : NON-STIMULANTS -

Aliskiren: a Novel, Orally Active Renin Inhibitor

Review Article Aliskiren: A Novel, Orally Active Renin Inhibitor Mohamed Saleem TS, Jain A1, Tarani P1, Ravi V1, Gauthaman K1 Department of Pharmacology, Annamacharya College of Pharmacy, Rajampet, AP, 1Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, Majhitar, East Sikkim - 737 136, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems play a major role in the regulation of human homeostasis Received 01 July 2009 mechanism, which are also involved in the development of hypertension and end-organ damage Accepted 07 July 2009 through activation of angiotensin II. Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may Available online 04 February 2010 reduce the development of end-organ damage to a greater extent than other antihypertensive Keywords: agents. Aliskiren is the first member of the new class of orally active direct renin inhibitors Aliskiren recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypertension. Hypertension Aliskiren directly inhibiting the renin and reducing the formation of angiotensin II, which is the Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system most effective mediator involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. The present Renin inhibitors review mainly focuses on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics and clinical aspects of aliskiren. In this respect, the review will improve the basic idea to understand the pharmacology of aliskiren, which is useful for the further research in cardiovascular disease. DOI: 10.4103/0975-8453.59518 Introduction inhibit renin have been available for many years but have been limited by low potency, bioavailability and duration of action. Activation of the renin-angiotensin (Ang)-aldosterone system However, a new class of nonpeptide, low molecular weight, orally [5] (RAAS) plays an important role in the development of hypertension active inhibitors has recently been developed. -

Genetic Modifiers of Hypertension in Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Α1–Deficient Mice

Amendment history: Corrigendum (August 2012) Genetic modifiers of hypertension in soluble guanylate cyclase α1–deficient mice Emmanuel S. Buys, … , Mark J. Daly, Kenneth D. Bloch J Clin Invest. 2012;122(6):2316-2325. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI60119. Research Article Vascular biology Nitric oxide (NO) plays an essential role in regulating hypertension and blood flow by inducing relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. Male mice deficient in a NO receptor component, the α1 subunit of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGCα1), are prone to hypertension in some, but not all, mouse strains, suggesting that additional genetic factors contribute to the onset of hypertension. Using linkage analyses, we discovered a quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 1 that was linked to mean arterial pressure (MAP) in the context of sGCα1 deficiency. This region is syntenic with previously identified blood pressure–related QTLs in the human and rat genome and contains the genes coding for renin. Hypertension was associated with increased activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Further, we found that RAAS inhibition normalized MAP and improved endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in sGCα1-deficient mice. These data identify the RAAS as a blood pressure–modifying mechanism in a setting of impaired NO/cGMP signaling. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/60119/pdf Research article Genetic modifiers of hypertension in soluble guanylate cyclase α1–deficient mice Emmanuel S. Buys,1 Michael J. Raher,1 Andrew Kirby,2 Shahid Mohd,1 David M. Baron,1 Sarah R. Hayton,1 Laurel T. Tainsh,1 Patrick Y. Sips,1 Kristen M. Rauwerdink,1 Qingshang Yan,3 Robert E.T. -

Renin Angiotensin System Modulates Mtor Pathway Through AT2R in HIVAN P

Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Journal Articles Academic Works 2014 Renin angiotensin system modulates mTOR pathway through AT2R in HIVAN P. Rai Northwell Health R. Lederman Northwell Health S. Hague Northwell Health S. Rehman Northwell Health V. Kumar Northwell Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles Part of the Nephrology Commons Recommended Citation Rai P, Lederman R, Hague S, Rehman S, Kumar V, Sataranatrajan K, Malhotra A, Kasinath B, Singhal P. Renin angiotensin system modulates mTOR pathway through AT2R in HIVAN. 2014 Jan 01; 96(3):Article 2441 [ p.]. Available from: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/2441. Free full text article. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors P. Rai, R. Lederman, S. Hague, S. Rehman, V. Kumar, K. Sataranatrajan, A. Malhotra, B. S. Kasinath, and P. C. Singhal This article is available at Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/2441 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Exp Mol Pathol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 June 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Exp Mol Pathol. 2014 June ; 96(3): 431–437. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.04.004. -

Aliskiren – an Orally Active Renin Inhibitor

REVIEW Aliskiren – an orally active renin inhibitor. Review of pharmacology, pharmacodynamics, kinetics, and clinical potential in the treatment of hypertension Kristina Allikmets Abstract: The importance of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in diseases such as hypertension, congestive heart failure and chronic renal failure has long ago been recognized. It Department of Drug Development and Medical Affairs, Nycomed Group, has also been established that inhibition of RAAS, using inhibitors of the angiotensin-converting Roskilde, Denmark enzyme (ACE) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), is an effective way to intervene with the pathogenesis of these disorders. Renin inhibitors block the RAAS at the highest level, at its origin, and might thus offer a new exciting approach for pharmacotherapy of arterial hyperten- sion. Aliskiren is the fi rst in a new class of orally active, non-peptide, low molecular weight renin inhibitors, and so far the only renin inhibitor that has progressed to phase III clinical trials. This review summarizes the available data on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of aliskiren and its clinical development for treatment of arterial hypertension. Keywords: aliskiren, hypertension, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, renin inhibition, essential hypertension Introduction The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays a key role in the regulation of blood pressure (BP) and volume homeostasis. Its importance in diseases such as hypertension, congestive heart failure and chronic renal failure has long ago been recognized and it has also been established that inhibition of RAAS is an effective way to intervene with the pathogenesis of these disorders (Ruggenenti et al 1999; Flather et al 2000; Turnbull 2003). -

New Use of Glutaminyl Cyclase Inhibitors

(19) TZZ _Z T (11) EP 2 481 408 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 01.08.2012 Bulletin 2012/31 A61K 31/4164 (2006.01) A61K 31/4184 (2006.01) A61K 31/422 (2006.01) A61K 31/4178 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11192085.6 A61K 31/433 A61K 31/5415 A61K 31/517 (2006.01) A61P 25/28 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 28.02.2008 A61P 29/00 A61P 3/08 A61K 45/06 (2006.01) (84) Designated Contracting States: • Hoffmann, Torsten AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR 06114 Halle / Saale (DE) HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MT NL NO PL PT • Cynis, Holger RO SE SI SK TR 06110 Halle / Saale (DE) • Demuth, Hans-Ulrich (30) Priority: 01.03.2007 US 892265 P 06120 Halle / Saale (DE) 14.03.2007 US 685881 (74) Representative: Hoffmann, Matthias et al (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in Maikowski & Ninnemann accordance with Art. 76 EPC: Patentanwälte 08717208.6 / 2 117 540 Kurfürstendamm 54-55 10707 Berlin (DE) (71) Applicant: Probiodrug AG 06120 Halle/Saale (DE) Remarks: This application was filed on 06-12-2011 as a (72) Inventors: divisional application to the application mentioned • Schilling, Stephan under INID code 62. 06130 Halle / Saale (DE) (54) New use of glutaminyl cyclase inhibitors (57) The present invention relates in general to an c. fibrosis, e.g. lung fibrosis, liver fibrosis, renal fibrosis, inhibitor of a glutaminyl peptide cyclotransferase, and d. -

Tekamlo (Aliskiren and Amlodipine) Tablets, for Oral Use Do Not Use with Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (Arbs) Or ACE Inhibitors Initial U.S

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION -----------------------DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS--------------- These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Tablets (aliskiren/amlodipine): 150 mg/5 mg, 150 mg/10 mg, 300 mg/5 mg, TEKAMLO safely and effectively. See full prescribing 300 mg/10 mg. (3) information for TEKAMLO. --------------------------------CONTRAINDICATIONS------------------------ Tekamlo (aliskiren and amlodipine) tablets, for oral use Do not use with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) or ACE inhibitors Initial U.S. Approval: 2010 (ACEI) in patients with diabetes (4) WARNING: FETAL TOXICITY -------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS----------------- See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. Avoid concomitant use with ARBs or ACEI in patients with renal When pregnancy is detected, discontinue Tekamlo as soon as impairment (GFR<60 mL/min) (5.2) Head and neck angioedema: Discontinue Tekamlo and monitor until possible. (5.1) signs and symptoms resolve. (5.3) Drugs that act directly on the renin-angiotensin system can Hypotension in volume- and/or salt-depleted patients: Correct cause injury and death to the developing fetus. (5.1) imbalances before initiating therapy with Tekamlo. (5.4) Increased angina or myocardial infarction with calcium channel blockers ----------------------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES---------------------- may occur upon dosage initiation or increase. (5.5) Contraindications: Concomitant use with ARBs or ACEIs in Impaired renal function: Monitor serum creatinine -

Combined Use of Calcium Channel Blockers and Inhibitors of the Renin–Angiotensin System for Treating Hypertension

Review Combined use of calcium channel blockers and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system for treating hypertension Reduced cardiovascular events and mortality have been reported for hypertensive subjects treated with dihydropyridine-type calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) in clinical trials. Recent evidence suggests that these agents may have vascular benefits that cannot be attributed to the reduction of blood pressure alone. Dihydropyridine-type CCBs and RAS blockers have been shown to improve endothelial activity while reducing inflammation. These changes in vascular activity have been confirmed by pulse wave analyses, which show a reduced impact of pressure wave reflections on central systolic blood pressure. In this article, we examine the separate and combined effects of CCB and RAS inhibition in reducing cardiovascular risk through enhanced vascular function. 1 KEYWORDS: aliskiren n angiotensin n calcium channel blockers n endothelial Yoshiko Mizuno , dysfunction n hypertension n inflammation n oxidative stress n renin Robert F Jacob2 & R Preston Mason† A number of structural and functional mecha- production through enzymatic mechanisms 1Department of Cardiovascular nisms have been identified in the pathogen- or by stimulating direct release by its redox Medicine, The University of Toyko, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan esis of hypertensive vascular disease, includ- congeners in a spontaneous fashion. While all 2Elucida Research LLC, PO Box 7100, ing endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress antihypertensive medications lower BP, certain 100 Cummings Center, Suite 135L, Beverly, MA 01915, USA and inflammation. The vascular endothelium drug classes have pleiotropic effects that may †Author for correspondence: controls vasomotor tone through the release of contribute to cardiovascular risk reduction. -

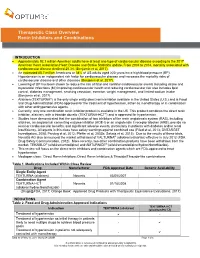

Therapeutic Class Overview Renin Inhibitors and Combinations

Therapeutic Class Overview Renin Inhibitors and Combinations INTRODUCTION Approximately 92.1 million American adults have at least one type of cardiovascular disease according to the 2017 American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics update. From 2004 to 2014, mortality associated with cardiovascular disease declined 25.3% (Benjamin et al, 2017). An estimated 85.7 million Americans or 34% of US adults aged ≥20 years have high blood pressure (BP). Hypertension is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and increases the mortality risks of cardiovascular disease and other diseases (Benjamin et al, 2017). Lowering of BP has been shown to reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events including stroke and myocardial infarctions (MI) improving cardiovascular health and reducing cardiovascular risk also includes lipid control, diabetes management, smoking cessation, exercise, weight management, and limited sodium intake (Benjamin et al, 2017). Aliskiren (TEKTURNA®) is the only single entity direct renin inhibitor available in the United States (U.S.) and is Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of hypertension, either as monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents. Currently, only one combination renin inhibitor product is available in the US. This product combines the direct renin inhibitor, aliskiren, with a thiazide diuretic (TEKTURNA-HCT®) and is approved for hypertension. Studies have demonstrated that the combination of two inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system (RAS), including aliskiren, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), provide no renal or cardiovascular benefits, and significant adverse events, particularly in patients with diabetes and/or renal insufficiency.