Thru-Hiking and Why People Do It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hueston Woods State Park to Eaton 14 Mi

CR 29 SR 732 SR 177 To Hamilton 14 mi. Hueston Woods State Park To Eaton 14 mi. Park Entrance MORNING SUN 6301 Park Office Road College Corner, Ohio 45003 SR 732 (513) 523-6347 - Park Office To Richmond 23 mi. (513) 664-3500 - Lodge SR 177 (513) 664-3500 - Lodge & Cabin Reservations Morning Sun Rd. LOCATION MAP Horse EATON Arena Four Mile Valley Rd. SR 732 OHIO INDIANA To Oxford 5 mi. L o o SR 177 SR 127 p Camden-College Corner Rd. Horseman’s Camp/ R CAMDEN SR 725 o Day-Use Area a Family d COLLEGE Hueston Woods Cabin CORNER State Park Area US 127 US 27 Disc Sled Hill Equestrian Standard Golf Overlook SR 732 Cabin Lodge Fossil Main Loop Rd. Area Collection OXFORD Fossil Area Collection E Mountain Bike TRAILS Area Trailhead 1 - Cedar Falls 7 - Blue Heron Wildlife Marina ACTON LAKE 2 - Sycamore 8 - Big Woods Area Group (625 ACRES UNLIMITED H.P., 3 - Pine Loop/Cabin 9 - Hedge Apple Camp NO WAKE) 4 - Mud Lick 10 - Indian Mound Fishing Pier Class B Hedge Row Rd. Sugar 5 - West Shore 11 - Gallion Run Dam Campground House 6 - Sugar Bush 12 - Equisetum Loop Bird Bird C Archery Banding LEGEND Viewing Range Area Park Office Camping Area Blind D 12 Camp Check-in/Camp Store Covered Bridge G Golf Course Nature Center Dog Park Picnic Area Basketball Court Pro Shop Picnic Shelter Park Boundary Class A Driving Latrine Hiking Trail Campground SR 27 - Oxford Range PICNIC AREAS Butler-Israel Rd. Brown Rd. Pioneer Farm Trailhead Parking Bridle Trail Museum A - Sycamore Grove Rev. -

The Indiana State Trails · Greenways & Bikeways Plan

THE INDIANA STATE TRAILS · GREENWAYS & BIKEWAYS PLAN STATE OF INDIANA Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR Governor State House, Second Floor Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Dear Trail Enthusiasts: With great excitement, I welcome you to travel the path down our state’s latest comprehensive trails plan. Not since our state park system was created has the state undertaken an outdoor initiative of this potential scope. This initiative will soon begin uniting our state’s disconnected routes and place every Hoosier within 15 minutes of a trail. The whole will be much greater than the sum of its parts and will benefit Hoosiers from all walks of life. We doubled state funding from $10 million to $20 million annually to take advan- tage of this unique network of opportunities, and at first glance this is a recreation initiative, but we intend it to be much more. Our trails plan will encourage healthy habits in Hoosiers, boost tourism and enhance Indiana’s ability to attract new investment and jobs. Our trail investments can deliver. As Hoosiers enjoy our new trails, they will be hiking, walking, and rid- ing over miles of new high-speed telecommunications and utility conduits. Access to outdoor recreation also ranks among the features potential companies seek for their employees when locating a business. Real success will require the help of local communities, businesses, and private philanthropies. Let’s join together as we create something that will be the envy of the nation! Sincerely, Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. HOOSIERS ON THE MOVE THE -

California Trail Corridor System Update

California Trail Corridor System • Existing or planned long distance trail routes • Identified in the California Recreational Trails Act, 1978 • Must meet 3 of 10 established criteria in California Recreational Trails Plan California Trail Corridors • Currently the 26 Trail Corridors in California are in various levels of development, planning, completion and public use. • Trail Corridors are in the backcountry, on the coast, in cities, suburbs, along rivers, through historic routes and on abandoned rail grades. Corridors with Substantial Progress or Completed • American Discovery Trail • Bay Area Ridge Trail • California Coastal Trail • Lake Tahoe Bikeway • Los Angeles River Trail • San Gabriel River Trail • Mokelumne Coast to Crest Trail • Pacific Crest Trail • San Francisco Bay Trail • San Joaquin River Trail • Santa Ana River Trail • Tahoe Rim Trail • Trans County Trail Corridors With Minimal Progress Characteristics: major gaps and minimal management These trails include: • Cuesta to Sespe Trail • Condor Trail • Merced River Trail • Whittier to Ortega Trail • Tuolumne Complex Trails Corridors With Little or no Progress • Redwood Coast to Crest Trail • Cross California Ecological Trail Heritage Corridors and Historic Routes: • Pony Express National Historic Trail 140 miles long in CA, along the Highway 50 Corridor, about 25 miles is in the El Dorado National Forest. • Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail Through 14 counties and 2 states, traces the 1,210 mile route of explorer Juan Bautista de Anza over dirt trails and roads close to the historic route. Next Steps • Maintain up-to-date database, contact information, mapping and planning progress of Trail Corridors from managing entities. • Compile information on new Trail Corridors currently not included in the system. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California Suzanna Theresa Montague B.A., Colorado College, Colorado Springs, 1982 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California A Thesis by Suzanna Theresa Montague Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Mark E. Basgall, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader David W. Zeanah, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Suzanna Theresa Montague I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, ___________________ Michael Delacorte, Ph.D, Graduate Coordinator Date Department of Anthropology iii Abstract of High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California by Suzanna Theresa Montague The study investigated pre-contact land use on the western slope of California’s central Sierra Nevada, within the subalpine and alpine zones of the Tuolumne River watershed, Yosemite National Park. Relying on existing data for 373 archaeological sites and minimal surface materials collected for this project, examination of site constituents and their presumed functions in light of geography and chronology indicated two distinctive archaeological patterns. First, limited-use sites—lithic scatters thought to represent hunting, travel, or obsidian procurement activities—were most prevalent in pre- 1500 B.P. contexts. Second, intensive-use sites, containing features and artifacts believed to represent a broader range of activities, were most prevalent in post-1500 B.P. -

Open Trail Report

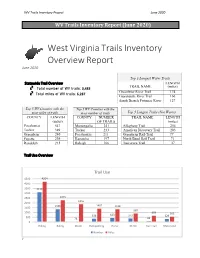

WV Trails Inventory Project June 2020 WV Trails Inventory Report (June 2020) West Virginia Trails Inventory Overview Report June 2020 Top 3 Longest Water Trails Statewide Trail Overview LENGTH TRAIL NAME (miles) Total number of WV trails: 3,483 Greenbrier River Trail 174 Total miles of WV trails: 6,287 Guyandotte River Trail 166 South Branch Potomac River 127 Top 5 WV Counties with the Top 5 WV Counties with the most miles of trails most number of trails Top 5 Longest Trails (Not Water) COUNTY LENGTH COUNTY NUMBER TRAIL NAME LENGTH (miles) OF TRAILS (miles) Pocahontas 547 Monongalia 251 Allegheny Trail 254 Tucker 389 Tucker 233 American Discovery Trail 203 Greenbrier 240 Pocahontas 211 Greenbrier Rail-Trail 77 Fayette 239 Kanawha 197 North Bend Rail Trail 71 Randolph 215 Raleigh 166 Tuscarora Trail 37 Trail Use Overview Trail Use 4500 4204 4000 3500 3110 3000 2500 2275 1856 2000 1346 1402 1338 1500 889 1000 669 565 336 433 373 500 329 24 89 0 Hiking Biking Water Backpacking Horse XC Ski Rail-Trail Motorized Number Miles r WV Trails Inventory Project June 2020 Trail Managers and Contacts Total number of managing organizations: 192 Total number of trail contacts in database: 368 Total number of trail contacts in database without email: 114 Total number of trail contacts in database without e-mail and phone number: 13 Total number of trail contacts not linked to trail database: 120 Management Organizations by Number of Trails 1600 1400 1519 1407 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 233 221 122 111 0 WV Division of Natural Resources US Forest Service (MNF) Hatfield-McCoy Regional Trail Authority National Park Service Wood County Parks Other (362) Management Organizations by Length in Miles WV Division of Natural Resources 2963 *Water trails account for 1448 miles US Forest Service (MNF) 821 Appalachian Trail Conservancy 702 National Park Service 467 Hatfield-McCoy Regional Authority 445 American Discovery Trail Society 173 Other (362) 1442 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500. -

American Discovery Trail

AMERICAN DISCOVERY TRAIL HORSE FRIENDLY PORTIONS OF THE TRAIL Delaware most of 45 miles Maryland/DC most of 267 miles West Virginia most of 276 miles Ohio/Kentucky most of 407 miles Southern Indiana most of 326 miles Northern Indiana most of 195 miles Southern Illinois most of 286 miles Northern Illinois most of 210 miles Missouri not much of 346 miles Kansas most of 574 miles Iowa most of 504 miles Nebraska ALL of 515 miles Southern Colorado most of 150 miles Northern Colorado most of 195 miles Western Colorado most of 586 miles Utah most of 560 miles Nevada ALL except 3 miles California parts of 389 miles DELAWARE The entire route through DE is road shoulder except the 1 mile in Cape Henlopen State Park. The trail in Cape Henlopen is designated bike/pedestrian, but equestrians can easily parallel the trail by following the road. MARYLAND and DC Horses must be trailered over Chesapeake Bay Bridge. Horseback riding is not allowed on the C&O Canal between Georgetown (mile 0) and Swains Lock (mile 16.6). Horses are not allowed in the Paw Paw Tunnel. Riders must take the tunnel hill trail that goes over the tunnel instead. Riders may not exceed the speed of a slow trot. Riders must dismount and walk their horses across aqueducts. Horses may not cross wooden footbridges, which are not designed to carry their weight. WEST VIRGINIA Dolly Sods area - Horses are allowed on the trail, as long as the group is 10 or less North Bend Rail Trail (72 miles) – horses are allowed Harrison County Rail Trail (< 4 miles) – horses are allowed Canaan to BlackWater Falls (8 miles) - if it is a group that fund-raises or rides for a cause in any way, they must have pre-approval. -

Across America Summer 2014

A Publication of the Partnership for the National Trails System Pathways Across America Summer 2014 AcrossPathways America Pathways Across America is the only national publication devoted to the news and issues of America’s national scenic and historic trails. It is published by the Partnership for the National Trails System under cooperative agreements with: Building Community... Department of Agriculture: USDA Forest Service Department of the Interior: National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Department of Transportation: The National Trails Federal Highway Administration Administration: Pathways Nationwide for Gary Werner [email protected] 608-249-7870 Editing and Design: Julia Glad Pooler [email protected] What is the Partnership for the National Trails System 222 S. Hamilton Street - Ste. 13 Madison, WI 53703 For information about the Partnership for the National Trails National Trails System? System or to learn how to contact any of our partner groups The National Trail System includes 3 main types visit the PNTS web site at: www.pnts.org. Unless otherwise of national trails: Scenic Trails, Historic Trails, indicated, all material in Pathways Across America is public and Recreation Trails. domain. All views expressed herein are perspectives of individuals working on behalf of the National Trails System Categories of National Trails: and do not necessarily represent the viewpoint of the federal National Scenic & Historic Trails agencies. NSTs and NHTs are designated by Congress (see specific Pathways serves as a communication link for the major descriptions below). The Partnership for the National Trails partners of the following national trails: System (see left) is the nonprofit dedicated to facilitating Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail stewardship of the Scenic and Historic Trails as a group. -

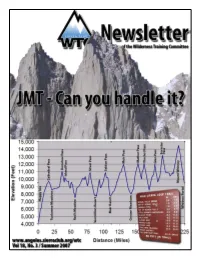

Wtc 1803C.Pdf

WTC Officers WTC Says Congratulations! By Kay Novotny See page 8 for contact info WTC Chair Scott Nelson Long Beach Area Chair KC Reid Area Vice Chair Dave Meltzer Area Trips Mike Adams Area Registrar Jean Konnoff WTC would like to congratulate 2 of their Orange County leaders on their recognition at the annual Area Chair Sierra Club Angeles Chapter Awards Edd Ruskowitz Banquet. This event took place on May 6th, 2007, Area Vice Chair at the Brookside Country Club in Pasadena. Barry John Cyran Holchin, right, who is an “M”rated leader, and who WTC Outings Chair and Area Trips divided his time last year between Long Tom McDonnell Beach/South Bay’s WTC groups 2 and 3, received a Area Registrar conservation service award. These awards are given Kirt Smoot to Sierra Club members who deserve special San Gabriel Valley recognition for noteworthy service they have ren- Area Chair dered to the Angeles Chapter. Dawn Burkhardt Bob Beach, left, another “M” rated leader, who is Area Vice Chair Shannon Wexler Long Beach/South Bay’s Group 1 assistant leader, Area Trips received the prestigious Chester Versteeg Outings Helen Qian Plaque, which is the highest outings leadership Area Registrar award conferred by the Angeles Chapter. It is James Martens awarded to a Sierra Club member who has pro- vided long-term and outstanding leadership in furthering the enjoyment and safety of the outings program. West Los Angeles Congratulations, Barry and Bob! We all appreciate your hard work and dedication to the WTC program. Area Chair Gerard Lewis Area Vice Chair Kathy Rich Area Trips Graduations Marc Hertz Area Registrar Graduations are currently scheduled for October 20 and 21 at Indian Cove in Joshua Tree National Park. -

Status Report on Trails and Greenways in the OKI Region January 2011

Status Report on Trails and Greenways in the OKI Region January 2011 Introduction The Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments is the federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for transportation planning in the Cincinnati metro area. In addition to our multi-county geographic area, our transportation planning responsibilities are also multi-modal as they include freight and personal movement by motorized and non-motorized modes. Shared use paths are a component of the regional transportation system including roadways. In some respects they can be considered a specialized network for non-motorized travel, just as the interstate highway system is for limited access motorized traffic. Like auto travel, the majority of non-motorized travel (bicycling and walking) still shares the local and arterial road system. While the regional trail system may be comprised of many local trail components, it excludes recreational loop trails less than four miles serving one park, walking paths and mountain bike trails. Like the highway system, OKI’s role for the regional trail system is to plan for a network of trail facilities, recommend guidelines for their construction and identify resources for implementation. This work is included the Regional Bicycle Plan. Implementation of these recommendations is normally initiated by local and state governments. The OKI staff provides technical assistance and coordination to trail groups and local governments in determining the detailed planning, design and funding requirements. A recommended resource for local trail groups is Trails for the Twenty-first Century available through Rails to Trails Conservancy. OKI also administers Transportation Enhancement funds, sub-allocated to us from the Federal Highway Administration through the Ohio Dept. -

25-Year Old American Adventurer-Horseman Becomes First Person to Complete the American Discovery Trail Equestrian Route

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Nicole McGrath Reverb Communications [email protected] 559.709.2601 25-Year Old American Adventurer-Horseman Becomes First Person to Complete the American Discovery Trail Equestrian Route Cape Henlopen State Park, Delaware, November 2, 2005 – Matt Parker, the 25- year old American adventurer, will complete the 5000+ miles of the American Discovery Trail (ADT) on horseback Thursday, November 3. With this ride of passage he will be the first person to complete the new ADT equestrian route. In addition, Parker will be the first person to complete the trail traveling from the west to east coast since the trail was created. Parker and his Appaloosa horse “Cincinnati” will finish his three-year journey as he rides into Cape Henlopen State Park, where the ADT meets the Atlantic Ocean, on Thursday November 3, 2005 at 10:00 am (EST). Parker will be greeted with a ceremony that will include U.S. Senator Tom Carper, State Senate Tribute, Susan "Butch" Henley, CEO, American Discovery Trail Society and Delaware Governor Ruth Ann Minner (invited). Parker, a native to Ann Arbor, Michigan started his journey in California back in May of 2003. His goal is to pioneer a horse trail across the United States and become the first person to traverse the 4,000+ miles. On a Racking Horse Named “Smokey” they crossed the deserts and mountains of Nevada and Utah facing many challenges. While resting at ranches along the way, he earned his keep by mending fences and herding cattle. In September 2003 he reached Manti-LaSal National Forest in Utah where he stopped for the winter. -

River to River Trail Supervisor’S Office 50 HWY 145 South Harrisburg, IL 62946 (800) 699-6637 2003

River to River Trail Supervisor’s Office 50 HWY 145 South Harrisburg, IL 62946 (800) 699-6637 www.fs.fed.us/r9/shawnee 2003 The River to River Trail spans 160 miles from Battery Rock on Length: 160 miles the Ohio River to Devil’s Backbone Park in Grand Tower on the Mississippi River. The trail is part of the American Discovery Trail Travel Time: Approximately 2 to 3 weeks that extends coast to coast from Point Reyes National Seashore in California to Cape Henlopen State Park in Delaware and spans Surface Type: Dirt, pavement, rock, gravel and grass more than 5,000 miles. Whether you’re experiencing southern Illinois for the first time or have loved this area for years, there are Difficulty Level: Easy – Difficult many surprises along the trail. If you want to truly experience the Shawnee National Forest and southern Illinois then the River to Recommended Season: All year. Summer brings River Trail is for you. usual midwest insects, cobwebs and extreme heat and humidity. The average daytime winter temperatures will be Trail Highlights in the 40’s, which is good hiking and riding weather. The River to River Trail passes through some of the most scenic areas in the country with a combination of plains, bayous, bluffs Facilities: At different points on the trail you will and upland forests. It crosses five of the seven Shawnee National encounter interpretive sites, restrooms, campgrounds, picnic Forest Wilderness’, as well as designated natural areas, Giant City areas and parking. State Park, Crab Orchard Wildlife Refuge, Ferne Clyffe State Park, historic landmarks and Devil’s Backbone Park.