Morphological, Genetic and Molecular Analysis of the Mating Process In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes For B.Sc. Botany 1st By Dr. Meenu Gupta Assistant Professor Botany J.D.W.C. Patna 1. Habit and Habitat of Ustilago: Ustilago, the largest genus of the family Ustilaginaceae is represented by more than 400 cosmopolitan species. Butler and Bisby (1958) reported 108 species from India. All species are parasitic and infect the floral parts of wheat, barley, oat, maize, sugarcane, Bajra, rye and wild grasses. The name Ustilago has been derived from a Latin word ustus meaning ‘burnt’ because the members of the genus produce black, sooty powdery mass of spores on the host plant parts imparting them a ‘burnt’ appearance. This black dusty mass of spores resembles soot or smut, therefore, commonly it is also known as smut fungus. The fungus is of much economic importance, because it causes heavy loss to various economically important plants. This genus is very common in U.P., Bihar, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh. 2. Symptoms of Ustilago: The symptoms appear only on the floral parts. The floral spikes turn black and remain filled with the smut spores. Ustilago produces two main types of symptoms: 1. The blackish powder of spores is easily blown away by the wind, leaving a bare stalk of inflorescence (Fig. 1 B). Species showing such symptoms are called loose smuts e.g., (a) Loose smut of oat caused by U. avenae (b) Loose smut of barley caused by U. nuda (c) Loose smut of wheat caused by U. nuda var. tritici. (Fig. 13A, B). (d) Loose smut of doob grass caused by U. -

The Ustilaginales (Smut Fungi) of Ohio*

THE USTILAGINALES (SMUT FUNGI) OF OHIO* C. W. ELLETT Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, The Ohio State University, Columbus 10 The smut fungi are in the order Ustilaginales with one family, the Ustilaginaceae, recognized. They are all plant parasites. In recent monographs 276 species in 22 genera are reported in North America and more than 1000 species have been reported from the world (Fischer, 1953; Zundel, 1953; Fischer and Holton, 1957). More than one half of the known smut fungi are pathogens of species in the Gramineae. Most of the smut fungi are recognized by the black or brown spore masses or sori forming in the inflorescences, the leaves, or the stems of their hosts. The sori may involve the entire inflorescence as Ustilago nuda on Hordeum vulgare (fig. 2) and U. residua on Danthonia spicata (fig. 7). Tilletia foetida, the cause of bunt of wheat in Ohio, sporulates in the ovularies only and Ustilago violacea which has been found in Ohio on Silene sp. forms spores only in the anthers of its host. The sori of Schizonella melanogramma on Carex (fig. 5) and of Urocystis anemones on Hepatica (fig. 4) are found in leaves. Ustilago striiformis (fig. 6) which causes stripe smut of many grasses has sori which are mostly in the leaves. Ustilago parlatorei, found in Ohio on Rumex (fig. 3), forms sori in stems, and in petioles and midveins of the leaves. In a few smut fungi the spore masses are not conspicuous but remain buried in the host tissues. Most of the species in the genera Entyloma and Doassansia are of this type. -

New Records of Bulgarian Smut Fungi (Ustilaginales)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sydowia Jahr/Year: 1991 Band/Volume: 43 Autor(en)/Author(s): Dencev C. M. Artikel/Article: New records of Bulgarian smut fungi (Ustilaginales). 15-22 ©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at New records of Bulgarian smut fungi (Ustilaginales) C. M. DENCEV Institute of Botany with Botanical Garden, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia 1113, Bulgaria DENCEV, C. M. (1991). New records of Bulgarian smut fungi (Ustilaginales). — Sydowia 43: 15-22. Entorrhiza casparyana, Entyloma corydalis, E. urocystoides, Sporisorium schweinfurthianum, Urocystis eranthidis, U. ficariae, U. ornithogali, U. primulicola, U. ranunculi, Ustilago bosniaca, U. thlaspeos, as well as sixteen fungus-host combina- tions in the Ustilaginales are reported as new to Bulgaria. Some previously published Bulgarian smut specimens are revised. Keywords: Ustilaginales, taxonomy, fungus list. Field investigations and revision of specimens in the Mycologi- cal Herbarium, (SOM) and of type material from BPI have yielded 11 species and 16 fungus-host combinations new to Bulgaria. Measurements of teliospores are given in the form (smallest observed-) mean ± standard error (-largest observed); except other- wise stated, 100 teliospores have been measured in each collection. Species previously unrecorded in Bulgaria 1. Entorrhiza casparyana (MAGNUS) LAGERH. - Hedwigia 27: 262. Sori in the roots, forming galls, ovoid or elongated, often bran- ched, up to 15 mm long, dark brown. - Teliospores globose or subglobose, (13-) 17.9 ± 0.3 (-28) x (12.5-) 17.1 ± 0.3 (-25.5) \im, whitish to light yellow; wall two-layered, the inner layer 0.5 — 1.5 [an thick, the outer layer variable in thickness (0.5 — 10 jim, including the ornamentations) and ornamentation (tuberculose or verrucose, sel- dom smooth). -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

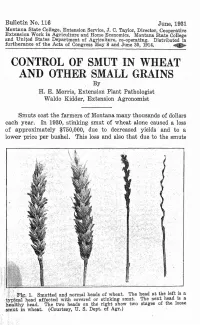

CONTROL of SMUT in WHEAT and OTHER SMALL GRAINS by H

Bulletin No. 116 June, 1931 Montana State College, Extension Service, J. C. Taylor, Director, Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. Montana State College and Uni~ed States Department of Agriculture, co-operating. Distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress ~ay 8 and June 30, 1.914. ~ CONTROL OF SMUT IN WHEAT AND OTHER SMALL GRAINS By H. E. Morris, Extension Plant Pathologist Waldo Kidder, Extension Agronomist Smuts cost the farmers of Montana many thousands of dollars each year. In 1930, stinking smut of wheat alone caused a loss of approximately $750;000, due to decreased yields and to a lower price per bushel. This loss and also that due to the smuts {..:Fig. 1. Smutted and normal heads of wheat. The head at the left ,is a typi:cal head affected with covered or stinking smut, The next, head IS a he'althy head. The two heads on the right show two stages of the loose smut in wheat. (-Courtesy,D. S. Dept. of Agr.) . ,( 2 MONTANA EXTENSION SERVICE of oats, barley and rye may be largely prevented by adopting the methods of seed treatment described in this bulletin. What Is Smut Smut is produced by a small parasitic plant, mould-like in appearance, belonging to a group called fungi (Fig. 2). Smut lives most of its life within and at the expense of the wheat plant. The smut powder, so familiar to all, is composed of myriads of spores which correspond to seeds in the higher plants. In the process of harvesting and threshing, these spores are dis· I Fig'. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Ustilago and Sporisorium Species (Basidiomycota, Ustilaginales) Based on Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) Sequences1

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen 976 Molecular phylogeny of Ustilago and Sporisorium species (Basidiomycota, Ustilaginales) based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences1 Matthias Stoll, Meike Piepenbring, Dominik Begerow, Franz Oberwinkler Abstract: DNA sequence data from the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the nuclear rDNA genes were used to determine a phylogenetic relationship between the graminicolous smut genera Ustilago and Sporisorium (Ustilaginales). Fifty-three members of both genera were analysed together with three related outgroup genera. Neighbor-joining and Bayesian inferences of phylogeny indicate the monophyly of a bipartite genus Sporisorium and the monophyly of a core Ustilago clade. Both methods confirm the recently published nomenclatural change of the cane smut Ustilago scitaminea to Sporisorium scitamineum and indicate a putative connection between Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium. Overall, the three clades resolved in our analyses are only weakly supported by morphological char- acters. Still, their preferences to parasitize certain subfamilies of Poaceae could be used to corroborate our results: all members of both Sporisorium groups occur exclusively on the grass subfamily Panicoideae. The core Ustilago group mainly infects the subfamilies Pooideae or Chloridoideae. Key words: basidiomycete systematics, ITS, molecular phylogeny, Bayesian analysis, Ustilaginomycetes, smut fungi. Résumé : Afin de déterminer la relation phylogénétique des genres Ustilago et Sporisorium (Ustilaginales), responsa- bles du charbon chez les graminées, les auteurs ont utilisé les données de séquence de la région espaceur transcrit interne (ITS) des gènes nucléiques ADNr. Ils ont analysé 53 membres de ces genres, ainsi que trois genres apparentés. Les liens avec les voisins et l’inférence bayésienne de la phylogénie indiquent la monophylie d’un genre Sporisorium bipartite et la monophylie d’un clade Ustilago central. -

The Smut Fungi Determined in Aladağlar and Bolkar Mountains (Turkey)

MANTAR DERGİSİ/The Journal of Fungus Ekim(2019)10(2)82-86 Geliş(Recevied) :21/03/2019 Araştırma Makalesi/Research Article Kabul(Accepted) :08/05/2019 Doi:10.30708.mantar.542951 The Smut Fungi Determined in Aladağlar and Bolkar Mountains (Turkey) Şanlı KABAKTEPE1, Ilgaz AKATA*2 *Corresponding author: [email protected] ¹Malatya Turgut Ozal University, Battalgazi Vocat Sch., Battalgazi, Malatya, Turkey. Orcid. ID:0000-0001-8286-9225/[email protected] ²Ankara University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Tandoğan, Ankara, Turkey, Orcid ID:0000-0002-1731-1302/[email protected] Abstract: In this study, 17 species of smut fungi and their hosts, which were found in Aladağlar and Bolkar mountains were described. The research was carried out between 2013 and 2016. The 17 species of microfungi were observed on a total of 16 distinct host species from 3 families and 14 genera. The smut fungi determined from the study area are distributed in 8 genera, 5 families and 3 orders and 2 classes. Melanopsichium eleusines (Kulk.) Mundk. & Thirum was first time recorded for Turkish mycobiota. Key words: smut fungi, biodiversity, Aladağlar and Bolkar mountains, Turkey Aladağlar ve Bolkar Dağları (Türkiye)’ndan Belirlenen Sürme Mantarları Öz: Bu çalışmada, Aladağlar ve Bolkar dağlarında bulunan 17 sürme mantar türü ve konakçıları tanımlanmıştır. Araştırma 2013-2016 yılları arasında gerçekleştirilmiş, 3 familya ve 14 cinsten toplam 16 farklı konakçı türü üzerinde 17 mikrofungus türü gözlenmiştir. Çalışma alanından belirlenen sürme mantarları 8 cins, 5 familya ve 3 takım ve 2 sınıf içinde dağılım göstermektedir. Melanopsichium eleusines (Kulk.) Mundk. & Thirum ilk kez Türkiye mikobiyotası için kaydedilmiştir. -

<I>Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces</I>

Persoonia 29, 2012: 55–62 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj REVIEW ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/003158512X660283 A review of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex A.R. McTaggart1,2,3,5, R.G. Shivas1,2, A.D.W. Geering1,2,5, K. Vánky4, T. Scharaschkin1,3 Key words Abstract The fungal genera Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces represent an unresolved complex. Taxa within the complex often possess characters that occur in more than one genus, creating uncertainty for species smut fungi placement. Previous studies have indicated that the genera cannot be separated based on morphology alone. systematics Here we chronologically review the history of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex, argue for its Ustilaginaceae resolution and suggest methods to accomplish a stable taxonomy. A combined molecular and morphological ap- proach is required to identify synapomorphic characters that underpin a new classification. Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces require explicit re-description and new genera, based on monophyletic groups, are needed to accommodate taxa that no longer fit the emended descriptions. A resolved classification will end the taxonomic confusion that surrounds generic placement of these smut fungi. Article info Received: 18 May 2012; Accepted: 3 October 2012; Published: 27 November 2012. INTRODUCTION TAXONOMIC HISTORY Three genera of smut fungi (Ustilaginomycotina), Ustilago, Ustilago Spo ri sorium and Macalpinomyces, contain about 540 described Ustilago, derived from the Latin ustilare (to burn), was named species (Vánky 2011b). These three genera belong to the by Persoon (1801) for the blackened appearance of the inflores- family Ustilaginaceae, which mostly infect grasses (Begerow cence in infected plants, as seen in the type species U. -

Archaeobotanical Evidence of the Fungus Covered Smut (Ustilago Hordei) in Jordan and Egypt

ANALECTA Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwen- huyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. Meijer, Luc Amkreutz, Bertil van Os, Liesbeth Theunissen, David R. Fontijn, Patrick Valentijn, Richard Jansen, Simone A.M. Lemmers, David R. Fontijn, Sasja A. van der Vaart, Harry Fokkens, Corrie Bakels, L. Bouke van der Meer, Clasina J.G. van Doorn, Reinder Neef, Federica Fantone, René T.J. Cappers, Jasper de Bruin, Eric M. Moormann, Paul G.P. PRAEHISTORICA Meyboom, Lisa C. Götz, Léon J. Coret, Natascha Sojc, Stijn van As, Richard Jansen, Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen, Menno L.P. Hoogland, Corinne L. Hofman, Alexander Geurds, Laura N.K. van Broekhoven, Arie Boomert, John Bintliff, Sjoerd van der Linde, Monique van den Dries, Willem J.H. Willems, Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwenhuyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. -

Two New Species of Anthracoidea (Ustilaginales) on Carex from North America

MYCOLOGIA BALCANICA 7: 105–109 (2010) 105 Two new species of Anthracoidea (Ustilaginales) on Carex from North America Kálmán Vánky ¹* & Vanamo Salo ² ¹ Herbarium Ustilaginales Vánky (H.U.V.), Gabriel-Biel-Str. 5, D-72076 Tübingen, Germany ² Botanic Garden and Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Received 28 November 2010 / Accepted 16 December 2010 Abstract. After a short revision of the genus Anthracoidea, two new species, A. multicaulis on C. geyeri and C. multicaulis, and A. praegracilis on C. praegracilis are described and illustrated. Key words: Anthracoidea, Anthracoidea multicaulis, Anthracoidea praegracilis, Carex, North America, smut fungi, Ustilaginales Introduction Materials and methods Th e genus Anthracoidea Bref. is a natural group in the Th e specimens of Anthracoidea, examined in this study are Anthracoideaceae (Denchev 1997) of the order Ustilaginales, listed in Table 1 and Table 2. parasitising members of Cyperaceae in Carex, Carpha, Fuirena, Sorus and spore characteristics were studied using dried Kobresia, Schoenus, Trichophorum and Uncinia (comp. Vánky herbarium specimens. Spores were dispersed in a droplet 2002: 28–29). Sori around the ovaries as black, globoid, of lactophenol on a microscope slide, covered with a agglutinated spore masses with powdery surface. Spores single, cover glass, gently heated to boiling point to rehydrate the pigmented (dark brown), usually ornamented with spines, spores, and examined by a light microscope (LM) at 1000x warts or granules, rarely smooth, often with internal swellings magnifi cation. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), dry or light-refractive areas. Spore germination results in two- spores were placed on double-sided adhesive tape, mounted celled basidia forming one or more basidiospores on each cell on a specimen stub, sputter-coated with gold-palladium, ca (Kukkonen 1963, 1964). -

Color Plates

Color Plates Plate 1 (a) Lethal Yellowing on Coconut Palm caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen. (b, c) Tulip Break on Tulip caused by Lily Latent Mosaic Virus. (d, e) Ringspot on Vanda Orchid caused by Vanda Ringspot Virus R.K. Horst, Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2141-8, 701 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 702 Color Plates Plate 2 (a, b) Rust on Rose caused by Phragmidium mucronatum.(c) Cedar-Apple Rust on Apple caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Color Plates 703 Plate 3 (a) Cedar-Apple Rust on Cedar caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi.(b) Stunt on Chrysanthemum caused by Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid. Var. Dark Pink Orchid Queen 704 Color Plates Plate 4 (a) Green Flowers on Chrysanthemum caused by Aster Yellows Phytoplasma. (b) Phyllody on Hydrangea caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen Color Plates 705 Plate 5 (a, b) Mosaic on Rose caused by Prunus Necrotic Ringspot Virus. (c) Foliar Symptoms on Chrysanthemum (Variety Bonnie Jean) caused by (clockwise from upper left) Chrysanthemum Chlorotic Mottle Viroid, Healthy Leaf, Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid, Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid, and Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (Mild Strain) 706 Color Plates Plate 6 (a) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Dieffenbachia caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi.(b) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Philodendron caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi Color Plates 707 Plate 7 (a) Common Leafspot on Boston Ivy caused by Guignardia bidwellii.(b) Crown Gall on Chrysanthemum caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens 708 Color Plates Plate 8 (a) Ringspot on Tomato Fruit caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus. (b, c) Powdery Mildew on Rose caused by Podosphaera pannosa Color Plates 709 Plate 9 (a) Late Blight on Potato caused by Phytophthora infestans.(b) Powdery Mildew on Begonia caused by Erysiphe cichoracearum.(c) Mosaic on Squash caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus 710 Color Plates Plate 10 (a) Dollar Spot on Turf caused by Sclerotinia homeocarpa.(b) Copper Injury on Rose caused by sprays containing Copper. -

Low Temperature During Infection Limits Ustilago Bullata (Ustilaginaceae, Ustilaginales) Disease Incidence on Bromus Tectorum (Poaceae, Cyperales)

Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2007; 17(1): 33Á52 Low temperature during infection limits Ustilago bullata (Ustilaginaceae, Ustilaginales) disease incidence on Bromus tectorum (Poaceae, Cyperales) TOUPTA BOGUENA1, SUSAN E. MEYER2, & DAVID L. NELSON2 1Department of Integrative Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, and 2USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Shrub Sciences Laboratory, Provo, UT, USA (Received 18 January 2006; returned 7 March 2006; accepted 4 April 2006) Abstract Ustilago bullata is frequently encountered on the exotic winter annual grass Bromus tectorum in western North America. To evaluate the biocontrol potential of this seedling-infecting pathogen, we examined the effect of temperature on the infection process. Teliospore germination rate increased linearly with temperature from 2.5 to 258C, with significant among-population differences. It generally matched or exceeded host seed germination rate over the range 10Á258C, but lagged behind at lower temperatures. Inoculation trials demonstrated that the pathogen can achieve high disease incidence when temperatures during infection range 20Á308C. Disease incidence was drastically reduced at 2.58C. Pathogen populations differed in their ability to infect at different temperatures, but none could infect in the cold. This may limit the use of this organism for biocontrol of B. tectorum to habitats with reliable autumn seedling emergence, because cold temperatures are likely to limit infection of later-emerging seedling cohorts. Keywords: Bromus tectorum, cheatgrass, downy brome, head smut, infection window, Ustilago bullata, weed biocontrol Introduction Bromus tectorum L. (downy brome, cheatgrass; Poaceae, Cyperales) is a serious and difficult-to-control weed of winter cereal grains in western North America (Peeper 1984) and is even more important as a weed of wildlands in this region (D’Antonio & Vitousek 1992).