Lean Manufacturing Principles Applied to the Engineering Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Measurement Techniques for Lean Companies

WASTE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES FOR LEAN COMPANIES Maciej Pieńkowski PhD student Wrocław University of Economics Komandorska 118/120, Wrocław, Poland [email protected] A B S T R A C T K E Y W O R D S Waste measurement, The paper is dedicated to answer the problem of lean manufacturing, lean metrics measuring waste in companies, which are implementing Lean Manufacturing concept. Lack of complex identification, quantification an visualization of A R T I C L E I N F O waste significantly impedes Lean transformation Received 07 June 2014 Accepted 17 June 2014 efforts. This problem can be solved by a careful Available online1 December 2014 investigation of Muda, Muri and Mura, which represent the essence of waste in the Toyota Production System. Measuring them facilitates complete and permanent elimination of waste in processes. The paper introduces a suggestion of methodology, which should enable company to quantify and visualize waste at a shop floor level. 1. Introduction Lean Management, originated from the Toyota Production System, is nowadays one of the most dominating management philosophies, both in industrial and service environment. One of the reasons for such a success is its simplicity. The whole concept is based on a common sense idea of so called “waste”. Removing it is the very essence of Lean Management. Despite seemingly simple principles, eliminating waste is not an easy task. Many companies, even those with many years of Lean experience, still struggle to clear the waste out of their processes. It turns out, that the most difficult part is not removing waste itself, but identifying and highlighting it, which should precede the process of elimination. -

Learning to See Waste Would Dramatically Affect This Ratio

CHAPTER3 WASTE 1.0 Why Studies have shown that about 70% of the activities performed in the construction industry are non-value add or waste. Learning to see waste would dramatically affect this ratio. Waste is anything that does not add value. Waste is all around, and learning to see waste makes that clear. 2.0 When The process to see waste should begin immediately and by any member of the team. Waste is all around, and learning to see waste makes this clear. CHAPTER 3: Waste 23 3.0 How Observations Ohno Circles 1st Run Studies/Videos Value Stream Maps Spaghetti Diagrams Constant Measurement 4.0 What There are seven common wastes. These come from the manufacturing world but can be applied to any process. They specifically come from the Toyota Production System (TPS). The Japanese term is Muda. There are several acronyms to remember what these wastes are but one of the more common one is TIMWOOD. (T)ransportation (I)ventory (M)otion (W)aiting (O)ver Processing (O)ver Production (D)efects. Transportation Unnecessary movement by people, equipment or material from process to process. This can include administrative work as well as physical activities. Inventory Product (raw materials, work-in-process or finished goods) quantities that go beyond supporting the immediate need. Motion Unnecessary movement of people or movement that does not add value. Waiting Time when work-in-process is waiting for the next step in production. 24 Transforming Design and Construction: A Framework for Change Look for and assess opportunities to increase value through waste reduction and elimination. -

Toyota Production System Toyota Production System

SNS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AN AUTONOMOUS INSTITUTION Kurumbapalayam (Po), Coimbatore – 641 107 Accredited by NBA – AICTE and Accredited by NAAC – UGC with ‘A’ Grade Approved by AICTE, New Delhi & Affiliated to Anna University, Chennai TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM 1 www.a2zmba.com Vision Contribute to Indian industry and economy through technology transfer, human resource development and vehicles that meet global standards at competitive price. Contribute to the well-being and stability of team members. Contribute to the overall growth for our business associates and the automobile industry. 2 www.a2zmba.com Mission Our mission is to design, manufacture and market automobiles in India and overseas while maintaining the high quality that meets global Toyota quality standards, to offer superior value and excellent after-sales service. We are dedicated to providing the highest possible level of value to customers, team members, communities and investors in India. www.a2zmba.com 3 7 Principles of Toyota Production System Reduced setup time Small-lot production Employee Involvement and Empowerment Quality at the source Equipment maintenance Pull Production Supplier involvement www.a2zmba.com 4 Production System www.a2zmba.com 5 JUST-IN-TIME Produced according to what needed, when needed and how much needed. Strategy to improve return on investment by reducing inventory and associated cost. The process is driven by Kanban concept. www.a2zmba.com 6 KANBAN CONCEPT Meaning- Sign, Index Card It is the most important Japanese concept opted by Toyota. Kanban systems combined with unique scheduling tools, dramatically reduces inventory levels. Enhances supplier/customer relationships and improves the accuracy of manufacturing schedules. A signal is sent to produce and deliver a new shipment when material is consumed. -

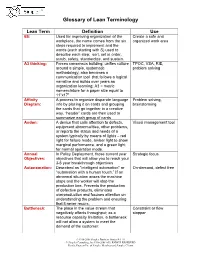

Glossary of Lean Terminology

Glossary of Lean Terminology Lean Term Definition Use 6S: Used for improving organization of the Create a safe and workplace, the name comes from the six organized work area steps required to implement and the words (each starting with S) used to describe each step: sort, set in order, scrub, safety, standardize, and sustain. A3 thinking: Forces consensus building; unifies culture TPOC, VSA, RIE, around a simple, systematic problem solving methodology; also becomes a communication tool that follows a logical narrative and builds over years as organization learning; A3 = metric nomenclature for a paper size equal to 11”x17” Affinity A process to organize disparate language Problem solving, Diagram: info by placing it on cards and grouping brainstorming the cards that go together in a creative way. “header” cards are then used to summarize each group of cards Andon: A device that calls attention to defects, Visual management tool equipment abnormalities, other problems, or reports the status and needs of a system typically by means of lights – red light for failure mode, amber light to show marginal performance, and a green light for normal operation mode. Annual In Policy Deployment, those current year Strategic focus Objectives: objectives that will allow you to reach your 3-5 year breakthrough objectives Autonomation: Described as "intelligent automation" or On-demand, defect free "automation with a human touch.” If an abnormal situation arises the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. Prevents the production of defective products, eliminates overproduction and focuses attention on understanding the problem and ensuring that it never recurs. -

Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017

Lean Manufacturing Techniques For Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published (2017) Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Cataloging in Publication Data/ Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry ILO Decent Work Team for North Africa and Country Office for Egypt and Eritrea- Cairo: ILO, 2017. ISBN: 978-92-2-130764-8 (print), 978-92-2-130765-5 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Introduction to Lean Waste and Lean Tools Shyam Sunder Sharma and Rahul Khatri

Chapter Introduction to Lean Waste and Lean Tools Shyam Sunder Sharma and Rahul Khatri Abstract In the turbulent and complex business environments, many Indian SMEs are facing stiff competition in the domestic as well as in the global market from their multinational counterpart. The concept of lean has gained prominence due to the fact that the resource based competitive advantages are no longer sufficient in this economy. Hence, lean is no longer merely an option but rather a core necessity for engineering industries situated in any part of the globe, if they have to compete successfully. Lean Manufacturing (LM) which provides new opportunities to create and retain greater value from the employee of the industry based on their core business competencies. The challenge of capturing, organizing, and disseminating throughout the aggregate business unit is a huge responsibility of the top manage- ment. The success of any industry depends on how well it can manage its resources and translate in to action. The adoption of lean manufacturing through effective lean practices depends on interpretations of past experiences and present informa- tion resides in the industry. Generally, in an industry, some tangible and intangible factors exist in the form of non-value adding activities which hinder the smooth lean implementation are known as lean manufacturing barriers (LMBs). Keywords: Lean, waste, kaizen, manufacturing 1. Introduction In the present worldwide situation, manufacturing industries are primar- ily handling difficulties from two directions. First, cutting edge manufacturing ways of thinking are arising, while the current techniques are getting outdated. Second, consumers demand is changing in very short of time. -

Lean Manufacturing

8 Lean manufacturing Lean manufacturing, lean enterprise, or lean production, often simply, "Lean", is a production practice that considers the expenditure of resources for any goal other than the creation of value for the end customer to be wasteful, and thus a target for elimination. Working from the perspective of the customer who consumes a product or service, "value" is defined as any action or process that a customer would be willing to pay for. Essentially, lean is centered on preserving value with less work. Lean manufacturing is a management philosophy derived mostly from the Toyota Production System (TPS) (hence the term Toyotism is also prevalent) and identified as "Lean" only in the 1990s. TPS is renowned for its focus on reduction of the original Toyota seven wastes to improve overall customer value, but there are varying perspectives on how this is best achieved. The steady growth of Toyota, from a small company to the world's largest automaker, has focused attention on how it has achieved this success. 8.1 Overview Lean principles are derived from the Japanese manufacturing industry. The term was first coined by John Krafcik in his 1988 article, "Triumph of the Lean Production System," based on his master's thesis at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Krafcik had been a quality engineer in the Toyota-GM NUMMI joint venture in California before coming to MIT for MBA studies. Krafcik's research was continued by the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) at MIT, which produced the international best-seller book co-authored by Jim Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos called The Machine That Changed the World.] A complete historical account of the IMVP and how the term "lean" was coined is given by Holweg (2007). -

Towards a Lean Integration of Lean

Mälardalen University Press Licentiate Theses No. 205 Mälardalen University Press Licentiate Theses No. 205 TOWARDS A LEAN INTEGRATION OF LEAN TOWARDS A LEAN INTEGRATION OF LEAN Christer Osterman 2015 Christer Osterman 2015 School of Innovation, Design and Engineering School of Innovation, Design and Engineering Copyright © Christer Osterman, 2015 ISBN 978-91-7485-208-0 ISSN 1651-9256 Printed by Arkitektkopia, Västerås, Sweden Abstract Integrating Lean in a process has become increasingly popular over the last decades. Lean as a concept has spread through industry into other sectors such as service, healthcare, and administration. The overwhelming experience from this spread is that Lean is difficult to integrate successfully. It takes a long time and requires large resources in the integration, as it permeates all aspects of a process. Lean is a system depending on both tools and methods as well as human effort and behavior. There is therefore a need to understand the integration process itself. As many companies have worked with the integration of Lean, there should be a great deal of accumulated knowledge. The overall intent of this research is therefore to examine how a current state of a Lean integration can be established, that takes into account the dualism of Lean regarding the technical components of Lean, as well as the humanistic components of Lean. Both issues must be addressed if the integration process of Lean is to be efficient. Through a literature review, eight views of Lean are established. Taking into consideration historical, foundational, and evolutionary tools and methods, systems, philosophical, cultural, and management views, a comprehensive model of Lean at a group level in a process is proposed. -

Lean Manufacturing and Lean Software Development

7. Lean manufacturing and Lean software development Lean software development Lean software development (LSD) is a translation of lean manufacturing and lean IT principles and practices to the software development domain. Adapted from the Toyota Production System, a pro-lean subculture is emerging from within the Agile community. Eliminate waste Lean philosophy regards everything not adding value to the customer as waste (muda). Such waste may include: unnecessary code and functionality delay in the software development process unclear requirements insufficient testing (leading to avoidable process repetition) bureaucracy slow internal communication In order to eliminate waste, one should be able to recognize it. If some activity could be bypassed or the result could be achieved without it, it is waste. Partially done coding eventually abandoned during the development process is waste. Extra processes and features not often used by customers are waste. Waiting for other activities, teams, processes is waste. Defects and lower quality are waste. Managerial overhead not producing real value is waste. A value stream mapping technique is used to identify waste. The second step is to point out sources of waste and to eliminate them. Waste-removal should take place iteratively until even essential-seeming processes and procedures are liquidated. Amplify learning Software development is a continuous learning process with the additional challenge of development teams and end product sizes. The best approach for 1 improving a software development environment is to amplify learning. The accumulation of defects should be prevented by running tests as soon as the code is written. Instead of adding more documentation or detailed planning, different ideas could be tried by writing code and building. -

8 Lean Manufacturing, Lean Enterprise and Lean Production

8 Lean Manufacturing, Lean enterprise and Lean Production Lean software development Lean software development (LSD) is a translation of lean manufacturing and lean IT principles and practices to the software development domain. Adapted from the Toyota Production System, a pro-lean subculture is emerging from within the Agile community. Origin The term lean software development originated in a book by the same name, written by Mary Poppendieck and Tom Poppendieck.The book presents the traditional lean principles in a modified form, as well as a set of 22 tools and compares the tools to agile practices. The Poppendiecks' involvement in the Agile software development community, including talks at several Agile conferences has resulted in such concepts being more widely accepted within the Agile community. Lean principles Lean development can be summarized by seven principles, very close in concept to lean manufacturing principles: 1.Eliminate waste 2.Amplify learning 3.Decide as late as possible 4.Deliver as fast as possible 5.Empower the team 6.Build integrity in 7.See the whole Eliminate waste Lean philosophy regards everything not adding value to the customer as waste (muda). Such waste may include: unnecessary code and functionality delay in the software development process unclear requirements insufficient testing (leading to avoidable process repetition) bureaucracy slow internal communication In order to eliminate waste, one should be able to recognize it. If some activity could be bypassed or the result could be achieved without it, it is waste. Partially done coding eventually abandoned during the development process is waste. Extra processes and features not often used by customers are waste. -

Basic Concepts of 5S

What is 5S principle? 5S Training of Trainers for Training Institutions Training material No. 13 Aren’t you frustrated in your workplace? Oh, this position makes me tired ! I cannot remember what/how to next… Where is that Why I am making document ? mistakes again and I cannot find it ! again Why we cannot Oh time is not enough communicate to complete this work! properly? Are you positive thinker or negative thinker? 3 Thinking negatively in inside box and give-up? 4 Work together and do something with big positive attitude? 5 Even you are positive thinker, you still need something to make your ideas realistic You need tools ! 6 There are useful tools 5S approaches 7 What is 5S ? • 5S is a philosophy and a way of organizing and managing the workspace and work flow with the intent to improve efficiency by eliminating waste, improving flow and reducing process unreasonableness. It is for improvement of working environment 8 What is 5S ? • 5S activities are to create good working environment through reduction of “Muri”, “Mura”, and “Muda” • It help to have a basis of strong management of workplace • What is “Muri”, “Mura”, and “Muda”? – Muri : overburden, unreasonableness or absurdity – Mura : unevenness or inconsistency, primarily with physical matter and the human spiritual condition – Muda : activity which is wasteful or doesn’t add value Source: http://blog.5stoday.com/category/muri-mura-muda/ 5S in Japanese/English/Swahili 5S is literally five abbreviations of Japanese terms with 5 initials of S. Japanese English Ki-Swahili S-1 Seiri -

Facilitator's Guide

Transforming Your Value Streams Facilitator’s Guide Production Leveling Before kanban can work we must level production. In this module you will earn what heijunka is. A step by step guide to presenting Gemba Academy’s 5S course to lean learners in all positions. This guide includes key points, discussion items, quiz questions and answers, and helpful tips. Using Gemba Academy’s online learning content, any facilitator can teach teams of people to understand and improve their processes. July 2017 Production Leveling Preparation and Lesson Plan Use this page to prepare for each training session. Resources • Gemba Academy videos • Online quizzes Prepare for a Successful Training Session • Watch videos and complete quizzes on your own at least one day before the training session. • Read this guide thoroughly and become familiar with the course content before presenting to others. • Prepare a suitable training room for your participants. • Prepare a computer with internet access and a projector or large screen. Test all equipment before the training session. • Have your Gemba Academy username and password ready. U:_______________ P:_______________ • Choose your quiz style. The most popular option is to use the online interactive quiz, answering questions as a group with open discussion. Another option is to print the PDF version and have participants complete the quizzes individually. Training Session Outline • Step 1: Introduce the session topic and content to the participants. • Step 2: Play a video. • Step 3: Lead a group discussion using this guide. Review key points, ask prepared questions and have participants fill in the Choose Your Quiz blanks in their workbooks.