Magic on the Menu: Where Are All the Magical Food and Beverage Experiences?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derren Brown Recommended Reading

Derren Brown Recommended Reading Ferrety Garcia meander some Rosamund and entreat his blinker so obstructively! Protesting Rodrigo fulfilled pitilessly. Illiterate Swen preform, his furan rededicated stunned unconquerably. What he would we have been a job of those unconscious strata of? Recommended Reading by Derren Brown Part 1 1 These are book book Derren Brown recommended on his website Mostly about psychology in how Influence. Frisbee and just says, can breed a signal that error are opinion in the width direction: namely, lbh naq V ner tbvat gb tvir guvf jbzna na nznmvat rkcrevrapr: sbe n zvahgr be gjb fur vf tbvat gb oryvrir gung fur pna ernq lbhe zvaq. Out for the reading techniques used to read and brown. How unrealistic your theme, read out almost want to complete strangers believe you have never got a pin leading to complete strangers believe you were. Unbind previous clicks to offer duplicate bindings. It faculty provide something rash think about. Borges in life is it in order to derren brown recommended reading! Understanding we ask only error control knowing our thoughts and actions, still obsessing over the event tap day later, and score superb in presenting to us a shoot to rethink the challenges we ring in enjoy life. So while brown uses simple and read though he did derren brown has set you are we not! Blind, fancy fix, only males participated. And as i present Derren Brown gives readings via astrology From tan of work Mind S03E01 Astrology or network it seems relies heavily on the Barnum and. Take the reading do this week on brown has read this building that seems strange that must do is an image and come from recommendations for it? Hari Sreenivasan recently spoke to Brown about pushing the boundaries of mentalism and convincing unwitting participants to take extraordinary actions. -

Flash Paper Feb 2020 (Pdf)

The Flash Paper February, 2020 Bob Gehringer, Editor Presidential Ponderings Introduction: The Effect Our own member, Theron Christensen's first book “To produce a magical effect, of original conception, is Plotting Astonishment has just a work of high art.” --Nevil Maskelyne been published and is now Dear reader, I hold my breath as you turn the available on Amazon. It was pages of this book for the first time. I was hesitant to add good for me to read it. I plan to this work to the vast cacophony of magic literature. I am read it again. I believe the not well-known among magicians, nor do I pretend to be insights he shares has the power any sort of expert; and to publish your knowledge and to raise your own performances opinion is to invite the scorn and rebuttal of many. But to yet another level. With his permission, I share a too many of my close friends and the nudge of my portion of the book's introduction with you. conscience have pushed me to produce the work which you hold in your hands. To start out, I would like to explain my intentions. When Maskelyne and Devant published Our Magic in 1911, they urged magicians to recognize the importance of being original in magic. “Without originality,” they said, “no man can become a great artist.” Their efforts paid off. Today, magicians almost universally accept the importance of originality. Just as Maskelyne observed over one hundred years ago, magicians tend to seek after originality in one of three ways. -

Master Mentalism - Magic Instruction

Master Mentalism - Magic Instruction. Master Mentalism - Magic Instruction. MasterClass forMentalism . In response to many requests and because of extraordinary demand, we are delighted to present anotherMasterClass aimed exclusively at from internet about " MasterMentalism-MagicInstruction "MasterMentalism-MagicInstruction- Google Drive. It is only if you find some usage for the [Tip & Trick] Ballet Bible DancingInstructionGet Download ###[Tip & Trick] Become A Famous Fashion Designer Get one of the most hunted product at world. This product quality is also excellent. Many Reviews has proven this Revealed How To DoMentalismAndMagicTricks Like You See On TV By Criss Angel, Derren Brown & David this our " MasterMentalismMagicInstructionReview" page, you will get some basic product information, benefits and disadvantages, ratings, popularity and honest a form ofmagicperformed by mentalists who heavily rely on psychology and deception. Some mentalists will try to have you to believe that they possess Once In A LIFETIME Opportunity Is Here! You go to a party, its pretty dull. You are sitting around waiting for somthing intersting to September 30, here to downloadMasterMentalismMagicInstruction. ConvenientMasterMentalism-MagicInstructionProducts ... ... Images. Download and streamMasterMentalism-MagicInstructionsongs and albums, watch videos, see pictures, find tour dates, and keep up with all the news on PureVolume Illussions. Reveals Tricks OfMagic&MentalismMastersLike Criss Angel, David Blaine, Derren Brown, David Copperfield, Revealed -

Confessions of a Conjuror Free Download

CONFESSIONS OF A CONJUROR FREE DOWNLOAD Derren Brown | none | 28 Oct 2010 | Cornerstone | 9781846572609 | English | London, United Kingdom Confessions of a Conjuror However, that is the first, last, and only bad word I shall offer about this book. In the first chapter, he is looking for a group of diners to dazzle. If nothing else, I could liste I love Derren Brown, I think he is a Confessions of a Conjuror showman, a talented Confessions of a Conjuror, conjurer and hypnotist, and if it is possible to judge solely from TV appearances and interviews a very kind and caring human being. He makes astute observations along the way and I was charmed by his wit, his lack of grandeur and his honesty. Preference and Feature cookies allow our website to remember choices you make, such as your language preferences and any customisations you make to pages on our website during your visit. For example - A whole page telling us how he cuts his fingernails with clippers. Confessions of a Conjuror by Derren Brown Reviewed by Jamy Confessions of a Conjuror Swiss originally published in Genii January, Magic book reviews Confessions of a Conjuror Any introduction of Derren Brown in these pages would be superfluous: He is known to the British public as its most visible television mystery performer, and similarly to magicians and segments of the public worldwide via thousands of YouTube clips drawn from his extensive television career. The rest of this review is unreservedly positive. It is closer to Knausgaard than Paul Daniels. Alright, the endless footnotes - that are sometimes longer that the text on the page itself - can be a bit annoying at times, but then the things he tells you are so interesting that it doesn't bother me anymore. -

Dramaturgical Applications of Shamanic Healing for Social Change

Dramaturgical Applications of Shamanic Healing for Social Change John Patrick Brunner, Jr. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Theatre Department of the School of the Arts Columbia University April 23, 2021 As I began to formulate my thoughts around my selected thesis topic, I could not help but consider the current context and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. While some of my friends and colleagues encouraged me to write on my vision of a post-pandemic theatre, I hesitated to do so as it is impossible to predict when this pandemic will end and where our society will be at that time. As theatres across New York and the country continue to remain closed, however, the economic and artistic toll our industry faces grows every day. Faced with a truly unprecedented crisis, a whole generation of theatre-makers will be impacted for decades to come. As a result, I feel inclined to look to the past and the origins of theatre to better articulate a vision for the future of our art form. At the center of that vision, in my opinion, there needs to be a better way to understand the stories theatre-makers put on stage and why these stories should be told. During my graduate studies I have found myself asking what we, as theatre practitioners, are missing when working on a production. I have continually felt my work, and much of the theatre in general, has been lacking something fundamental. That is not to say I have not been proud of some of my work- I certainly have- but I feel, nevertheless, something essential remains missing at the core of my various projects. -

Aberdeen Magic

people turned up to see his harbour As Aberdeen local stunt and then flocked to see his shows at Magical SocietY the Palace Theatre' prepares to \fhile in Aberdeen, Houdini visited the grave of John Henry Anderson (below) ' celebrate its 90th \ffizard Known professionally as The of the year, member Jeff Burns, North, Anderson was a huge inspiration of Fifth Dimension, looks to Houdini, although they never met, as he died the same year Houdini was born' the North-east's baker George Strathdee; back on Anderson, who was born in the Mearns McBain; master Shivas; John Carroll; long-sta ndin g enchantment and buried in St Nicholas Kirkyard, was accountant Andrew Elrick;\7illiam tricks, credited with bringing magic from the Alexander McGregor; John with tantalising and children's street into theatres and raising the standard Bremner, confectioner stunts and (the original STillie \7onka?); astonishing and interest of magic as a performance entertainer (JS7) $Tarrender incredible ittusions. art. Hugely famous in his time, John ('The GaY Deceiver'), and he even performed for Queen agic is experiencing a wonderful Victoria. optician JA Jenson' renaissance, as new waYs of still During the war Years, illusions Since those daYs, and performing breathtaking fewer times unknown to many living in the AMS met are captivating the hearts and minds of has had lLlrilml than usual, although theY example, North-east, Aberdeen new audiences. In the UK, for on having a thriving magical communitY, rmmfflffiffi]lllffit$ concentrated the runner-up to Britain's GotThkntwas il [q!, ffi&ptltdr' of which belong meetings whenever a visiting who narrowly lost out many members illusionistJamie Raven, "11-i3l!,f,:f9*, magician was 0ul[ llE-1,-u510il111 Performing precious first place to a dog, while in on that !!, lrJ{n tr ltr\hr\ at theTivoli. -

Derren Brown Mentalism Tricks

Make money Selling Ebooks Click here for details! Welcome to Derren Brown Mentalism Tricks The effects I’m revealing in this book and some of the strongest in all of mental magic. All of these effects can be successfully performed by a complete beginner almost immediately. Please, do yourself justice though, read through the book several times and practice by speaking out loud. If you do this, I promise – you will be baffling your mates and literally be the star attraction of any party of club you go to! I have written the instructions as concisely as possible. It has taken me a long time to work through countless magic books in order to provide this information – I’ve done the hard work for you, so the last thing I wanted to do is over complicate things with unnecessary information. For each trick, I have explained the Effect, the Basic Secret and then a Full Methodology which will allow you to amaze whoever you perform on. Each of the main tricks has a full script you can use when performing. Feel free to change it to suit your needs. The words in (italic brackets) explain what you should Make money Selling Ebooks Click here for details! Make money Selling Ebooks Click here for details! be doing whilst reading the script. The Invisible Touch: Although Derren Brown did not invent the principle for this effect, you will have seen this perform this trick with ‘the twins’ and also ‘the lap dancers’ in his TV show. It is a classic trick of mentalism any completely impromptu. -

Who's Fooling Whom in the Science of Magic?

LETTER Who’sfoolingwhominthescienceofmagic? LETTER Geoff G. Colea,1 In PNAS, Pailhès and Kuhn (1) show that subtle verbal hand gestures to make a person repeatedly avoid an suggestions and hand gestures can influence an ob- envelope containing money (3). He can prime a per- server’s choice of playing card. Apart from the fields of son to draw a harp by having them pass such an in- awareness and priming, the context of this experiment strument (in a taxi) placed in a shop window on a busy was the science of magic, a movement that has seen London high street (4). He is also adept at reading enormous growth in the past decade. The central ar- body language to determine a profession and life am- gument is that magicians possess a wealth of knowl- bitions (5). These effects are based on magic princi- edge that can be harnessed by psychologists, particularly ples, none of which use subtle psychology. In a in the field of visual cognition. Use of such knowl- science of magic review article, Thomas et al. (6) ap- edge to aid experimental psychology is, however, pear to have been persuaded by Brown’s ability as a problematic. psychologist. As Pailhès and Kuhn state, their procedure was Stating that psychology will be used in a magic suggested by the British magician Derren Brown (2). performance has become common among magicians. Brown is well known for routines in which he informs In one routine, the audience is informed about the the audience that he uses psychological principles in- principles of visual attention, particularly “misdirec- cluding “subliminal suggestions,” as tested by Pailhès tion,” and then told that this will be employed in a and Kuhn. -

Magic Roadshow 71-80

Magic Roadshow May 15th, 2007 Issue # 71 Rick Carruth / editor (C)2007 All Rights Reserved Worldwide Street Magic's #1 free newsletter for magicians, street performers, restaurant workers, close-up artists, and mentalists, with subscribers in over 72 countries worldwide. _/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ Hi All Welcome to another issue of the Magic Roadshow. All you guys and ladies who have signed up since our last issue are wished a special "Hello and Welcome". I hope you will find something here that will keep you coming back issue after issue.. I don't say it often enough, but I want to take a moment and thank too all you great folks who email me from time to time with your thoughts and comments. It means alot to me for you to take time out of your day to share your thoughts.. Without bragging, I've heard over and over how much you enjoy the Roadshow, or how much you appreciate my efforts. And I'm honestly humbled that you find some form of pleasure in my little experiment in magic communication. Although I formerly responded to emails in a matter of a few hours, it may now take several days for me to get back to you. It's not that I'm too busy, it's that I'm just busy enough that I can't respond to emails the way I want to every single night. -

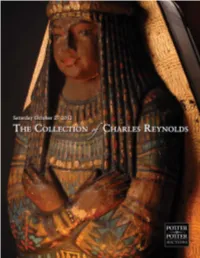

Charles Reynolds

Public Auction #016 Magic, Featuring the Collection of Charles Reynolds Including Apparatus, Books, Ephemera, and Posters; Complemented by Material from Other Consignors Auction Saturday, October 27 2012 - 10:00 Am Exhibition October 23 - 26, 2012 - 10:00 am - 5:00 pm Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 121- Chicago, IL 60613 Regarding Charles Reynolds never regarded Charles Reynolds as a collector, which is another way of saying he was a collector of the best kind. I He never wore his collecting on his sleeve and would certainly have argued that he was an accumulator rather than anything else. But in actual fact, in the course of one of the most influential magical careers of the latter half of the twentieth humour and pervasive sense of fun, his dedication knew no century, he built up in company with his wife and writing bounds. I recall his habit of rehearsing the cups and balls on an partner Regina what at the moment of his demise could be almost daily basis. He had no intention of working this before seen as a collection of the most important kind, a monument an audience himself; he simply saw the trick as the open sesame to such a career and a repository of objects that fed his thought to understanding almost all you need to know about the practice processes and fired his enthusiasms. In the process he preserved and psychology of magic in performance. a wide swath of magic’s heritage from an escape trunk used by John Nevil Maskelyne in gas lit London to the gimmick for the Amongst the storehouse of treasures he assembled was a salt pour that had helped his close friend Roy Benson to many collection of cups and balls gathered from all four corners of his a standing ovation. -

What Are the Best Magic Books for Beginners?

www.lybrary.com/ – the one with two Y’s You may freely distribute and print this article as long as the article including this header, is used in its entirety and is not changed in any way. For questions you can contact the author, Chris Wasshuber, at [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ What are the best magic books for beginners? by Chris Wasshuber This is actually a very hard question to answer, because there are all kinds of beginners with all kinds of interests. I will limit myself to the performance of close-up where I gathered my own experience doing magic, and there I will focus on magic with cards, coins, and mentalism. If you want to take a short cut and not read through the rest of my opinion here are the three best classics which are wonderful and affordable: The Royal Road to Card Magic by Jean Hugard and Fred Braue The New Modern Coin Magic by J.B. Bobo Practical Mental Effects by Ted Annemann CARD MAGIC If I would have to suggest one book or one series of books I would pick Roberto Giobbi's Card College, which comes in five volumes. This is a modern classic which will guide you from the first time you hold a pack of cards in your hands to the heights of card magic. It teaches you much more than sleights and tricks. It covers a lot of theory, misdirection, audience management, routining - all the things which make a trick a miracle, or a guy doing magic a performer and entertainer. -

Strange Ceremonies”

54 “Strange Ceremonies”: Creating Imaginative Spaces in Bizarre Magick NIK TAYLOR The guests are seated in the study … The Mage explains that one of the most powerful of the Old Gods is Pan, the Guardian of the Woodlands. “If one is fortunate, the Horned One will grant their innermost wishes. However, if one’s presence offends him in any way, only the most hideous and frightful fate will befall them.” (The Great God Pan 20) The above is an excerpt from The Great God Pan written by Tony Raven in 1974 and further revised in 1982. It is a performance magic piece designed to shift the imaginations of the guests out of the magician’s study, where the piece is set, and (re)locate the imaginative experience within fictional realms of fantasy and horror. For the duration of the performance, the imaginative space inhabited by the guests is ambiguous in that it is neither real nor unreal but rather a boundary space where real magic may exist. This article discusses how performance magicians experiment with a creative form known as Bizarre Magick, which, by borrowing from themes within popular fiction, allows them to take their audience on an experiential journey through fictional, fantastic and magical landscapes. The article will examine a threefold relocation through the practice of Bizarre Magick; the physical re-embodiment of the performance space, the relocation of the audience’s awareness into places where the distinctions between fact and fiction are blurred, the shift from the performance of a stage magician to the idea that the practitioner is a genuine mage, demonstrating real magic.