Meet the Doulas Helping the Terminally Ill Face Death with a Smile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Commonwealth University Volunteer Doula Program Training Manual Kathleen M

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass School of Nursing Publications School of Nursing 2015 Virginia Commonwealth University Volunteer Doula Program Training Manual Kathleen M. Bell Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Susan L. Linder Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/nursing_pubs Part of the Maternal, Child Health and Neonatal Nursing Commons Copyright © 2015 The Authors Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/nursing_pubs/16 This Curriculum Material is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Nursing at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Nursing Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Virginia Commonwealth University Volunteer Doula Program Training Manual “Empowerment, advocacy and support for one of life’s greatest journeys.” 1 Reflection and Discussion Why are you here? Why did you decide to do this doula training? What experiences do you have with birth, and how have they shaped your desire to participate in this program? What does it mean to be a doula with the VCU School of Nursing? What other reflections do you have? 2 Table of Contents 1. An overview of birth: Statistics and trends………………page 4-6 2. Birth workers and their roles………………...……………pages 7-10 3. You are a doula! Your birth-bag and preparation………..pages 11-14 4. Anatomy and Physiology of birth………………………...pages 15-18 5. Hormonal regulation of labor and birth…………………..pages 19-21 6. Pharmacologic management of labor…………………….pages 22-26 7. -

Palynology of Badger Coprolites from Central Spain

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 226 (2005) 259–271 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Palynology of badger coprolites from central Spain J.S. Carrio´n a,*, G. Gil b, E. Rodrı´guez a, N. Fuentes a, M. Garcı´a-Anto´n b, A. Arribas c aDepartamento de Biologı´a Vegetal (Bota´nica), Facultad de Biologı´a, 30100 Campus de Espinardo, Murcia, Spain bDepartamento de Biologı´a (Bota´nica), Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Auto´noma de Madrid, 28049 Cantoblanco, Madrid, Spain cMuseo Geominero, Instituto Geolo´gico y Minero de Espan˜a, Rı´os Rosas 23, 28003 Madrid, Spain Received 21 January 2005; received in revised form 14 May 2005; accepted 23 May 2005 Abstract This paper presents pollen analysis of badger coprolites from Cueva de los Torrejones, central Spain. Eleven of fourteen coprolite specimens showed good pollen preservation, acceptable pollen concentration, and diversity of both arboreal and herbaceous taxa, together with a number of non-pollen palynomorph types, especially fungal spores. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the coprolite collection derives from badger colonies that established setts and latrines inside the cavern over the last three centuries. The coprolite pollen record depicts a mosaic, anthropogenic landscape very similar to the present-day, comprising pine forests, Quercus-dominated formations, woodland patches with Juniperus thurifera, and a Cistaceae- dominated understorey with heliophytes and nitrophilous assemblages. Although influential, dietary behavior of the badgers does not preclude palaeoenvironmental -

Bugs, Bones & Botany Workshop October 30-November 4, 2016 Gainesville, Florida

Bugs, Bones & Botany Workshop October 30‐November 4, 2016 Gainesville, Florida October 30, 2016 Classroom Lecture Topics 1. Entomology: History & Overview of Entomology, Dr. Jason 8AM‐12 PM Byrd 2. Anthropology: Introduction to Forensic Anthropology, Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: Using Botanical Evidence in a Forensic Investigation, Instructor: Dr. David Hall 4. Crime Scene: Search & Field Recovery Techniques, Gravesite excavation, begin 1‐5 PM Field Topic 1. Entomology: Field Demonstration of Collection Procedures, Instructor: Dr. Jason Byrd 2. Anthropology: Hands‐on Skeletal Analysis Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: Where Plants Grow & Mapping/Collecting Equipment, Instructor: Dr. David Hall November 1, 2016 Classroom Topic 1. Entomology: Processing a Death Scene for Entomological 8‐12 AM Evidence, Instructor: Dr. Jason Byrd 2. Anthropology: Human and Nonhuman Skeletal Anatomy, Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: Characteristics of Plants, Instructor: Dr. David Hall 1‐5 PM Field topic 1. Entomology: Collection of Entomological Evidence Instructor: Dr. Jason Byrd 2. Anthropology: Students will excavate buried remains, Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: Collecting Botanical Evidence & Mapping Surface Scatter, Instructor: Dr. David Hall November 2, 2016 Classroom Topic 1. Entomology: Estimation of PMI Using Entomological Evidence, 8 AM – 12 PM Instructor: Dr. Jason Byrd 2. Anthropology: Methods of Human Identification Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: When to call a Forensic Botanist Instructor: Dr. David Hall 1‐5 PM Field Topic 1. Entomology: Continue Processing of Entomological Evidence, Instructor: Dr. Jason Byrd 2. Anthropology: Continue Processing Anthropological Evidence, Instructor: Dr. Mike Warren 3. Botany: Continue Processing Botanical Evidence & Surface Scatter, Instructor: Dr. David Hall November 3, 2016 Classroom Topic 1. -

How I Set up My Own Body Farm by Jennifer Dean

How I Set Up My Own Body Farm By Jennifer Dean To prepare for a new forensic science elective at Camas High School, and determined to make this new course an exciting application of biology and chemistry principles, I began by collecting forensic science resources, ordering books and enrolling in the local community college course on forensic science. I spent every extra hour soaking up as much as I could about this field during the “time off” teachers get in the summer. I was particularly fascinated by the fields of forensic entomology and anthropology. From books such as Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach and Dr. Bill Bass’s work around the creation of a human body farm at the University of Tennessee Forensic Anthropology Center, I decided to create something similar for our new high school forensic science program. As we met for dinner after a day of revitalizing workshops in Seattle at an NSTA conference, I shared my thoughts about the creation of an animal body farm with my talented and dedicated colleagues. These teachers have a passion for their students and their work. I felt free to share these ideas with them and know I’d be supported in making it a reality. As the Science Department, we formally agreed to dedicate ourselves to submitting grants to make it a reality. Back at work, I sent copies of the farm proposal to my immediate supervisors, and they responded with letters of support. The next step was getting the farm started—with or without grant money—because the first class of forensic science would be starting in the fall. -

Preservation of Buried Human Remains in Soil by Map Unit, Soil Survey of the State of Connecticut

U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service CONNECTICUT Preservation of Buried Human Remains in Soil This bone was located in a Hadley silt loam soil (map unit 105). Hadley soils are rated as having a high potential for preservation of buried remains. Deborah Surabian, Soil Scientist Natural Resources Conservation Service Tolland, Connecticut December 2012 USDA is an equal opportunity employer and provider. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................... 1 USE CONSTRAINTS .................................................................................................... 1 FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE PRESERVATION ................................................. 2 BURIAL IN SOIL ......................................................................................................... 3 EVALUATION CRITERIA ........................................................................................ 4 CONNECTICUT CASE STUDY A ............................................................................. 9 CONNECTICUT CASE STUDY B ............................................................................ 10 CONNECTICUT CASE STUDY C ........................................................................... 11 CONNECTICUT CASE STUDY D .......................................................................... -

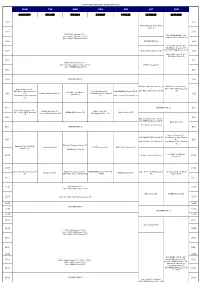

FOX Program Schedule August(Easiness)

FOX Program Schedule August(easiness) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 4:00 4:00 American Horror Story: Freak Show (S) 4:30 4:30 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / 7th~ NAVY NCIS Season7 (S) / FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY JUL. 25th~ NAVY NCIS Season8 (S) 2nd NAVY NCIS Season12 (S) 5:00 INFORMATION (J) / 5:00 FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY AUG. 9th NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / 5:30 Modern Family Season5 (S) 16th NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) 5:30 / 23rd Castle Season6 (S) / 30th Battle Creek (S) 6:00 6:00 Sleepy Hollow Season2 (S) / 13th~ Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) / BONES Season9 (B) 27th~ BONES Season8 (S) 6:30 6:30 7:00 INFORMATION (J) 7:00 Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / New Girl Season4 (S) / / 9th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 24th Modern Family Season5 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 29th Major Crimes Season3 (S) (S) How I Met Your Mother (S) / Modern Family Season5 (S) 27th Modern Family Season5 / 7:30 Season5 (S) 7:30 31st Modern Family Season6 (S) 28th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) (S) 8:00 INFORMATION (J) 8:00 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / Battle Creek (B) / 10th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 HOMELAND Season1 (S) Castle Season 6 (S) 11th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 27th Wayward Pines (S) (S) 8:30 8:30 New Girl Season4 (S) (~9:00) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) Battle Creek (S) / 8th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 9:00 INFORMATION (J) 9:00 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 23rd Modern Family Season5 9:30 / (S) / 9:30 29th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) 30th Modern Family -

The Bare Bones of Social Commentary in Kathy Reichs’ Fiction

THE BARE BONES OF SOCIAL COMMENTARY IN KATHY REICHS’ FICTION Carme Farre-Vidal Universidad de Lérida Abstract Resumen Detective fiction has popularly been Tradicionalmente, la novela policíaca ha sido considered a light form of literary considerada como una forma literaria de entertainment. However, many of this mero entretenimiento e intranscendente. Sin genre’s practitioners underline the embargo, muchos de los escritores de este way that their novels engage with género subrayan que sus novelas están contemporary social issues, as a close comprometidas con las cuestiones sociales reading of the texts may reveal. Kathy contemporáneas, tal y como se desprende de Reichs’ fiction is no exception. In this una lectura atenta de sus textos. En este sense, her Brennan series may be sentido, la novelística de Kathy Reichs no es analysed as prompting the reader to una excepción y su serie Brennan puede set out on a journey of discovery in plantearse como una forma de ficción que different ways. This article argues that busca trascender y suscitar en el lector un content and form work hand in hand viaje iniciático. Este artículo sostiene que at the service of Kathy Reichs’ social contenido y forma tienden a equiparar la feminist agenda and that just as the actividad forense y la agenda feminista de many times bare bones found at the Kathy Reichs, y que, así como en la primera crime scene point to both the victim’s los huesos humanos encontrados en la escena and criminal’s identity, they del crimen revelan tanto la identidad de la eventually become suggestive of how víctima como la del criminal, la segunda our contemporary society works. -

Zebra Manual: a Reference Handbook for Bioterrorism Agents

Arizona Department of Health Services Division of Public Health Services Office of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response 602-364-3289 Visit Our Website at http://www.azdhs.gov/phs/edc/edrp/index.htm Division of Public Health Services Office of the Assistant Director Public Health Preparedness Services th 150 N. 18 Avenue, Suite 150 JANET NAPOLITANO, GOVERNOR Phoenix, Arizona 85007 CATHERINE R. EDEN, DIRECTOR (602) 364-3289 (602) 364-3265 FAX Date: September 7, 2004 Dear Infection Control Personnel: Dear Health Care Professionals: Dear Public Health Professionals: Re: ZEBRA MANUAL: A REFERENCE HANDBOOK FOR BIOTERRORISM AGENTS Infection control personnel, healthcare providers and public health personnel need to know how to recognize symptoms of exposure to a bioterrorism agent. The Arizona Department of Health Services is distributing this updated version of the Zebra Manual to assist you in responding properly to a possible patient exposure to such an agent. The medical school adage, “when you hear hoof beats, think horses, not zebras” has a new twist in this age of threats of bioterrorism. We can learn how to recognize a zebra among the horses by increasing our awareness of the clinical syndromes associated with each potential bioterrorism agent. This enhanced Zebra Manual contains fact sheets, diagnostic guidelines, and infection control information for all Category “A” and “B” biological agents, as well as extensive smallpox information. If you have questions about specific diseases or about disease reporting, please contact your County Health Department or visit our web site: www.azdhs.gov/phs/edc/edrp/index.htm Sincerely, Sincerely, David M. Engelthaler, M.S. -

The Nikumaroro Bones Identification Controversy: First-Hand Examination Versus Evaluation by Proxy — Amelia Earhart Found Or Still Missing?

The Nikumaroro bones identification controversy: First-hand examination versus evaluation by proxy — Amelia Earhart found or still missing? Item Type Article Authors Cross, Pamela J.; Wright, R. Citation Cross PJ and Wright R (2015) The Nikumaroro bones identification controversy: First-hand examination versus evaluation by proxy — Amelia Earhart found or still missing? Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 3: 52-59. Rights (c) 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Full-text reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Download date 01/10/2021 02:19:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7286 The Nikumaroro Bones Identification Controversy: First-hand Examination versus Evaluation by Proxy – Amelia Earhart Found or Still Missing? Pamela J. Cross1* and Richard Wright2 *1Archaeological Sciences, University of Bradford, Bradford UK, [email protected] 2Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, University of Sydney, Australia Abstract American celebrity aviator Amelia Earhart was lost over the Pacific Ocean during her press-making 1937 round-the-world flight. The iconic woman pilot remains a media interest nearly 80 years after her disappearance, with perennial claims of finds pinpointing her location. Though no sign of the celebrity pilot or her plane have been definitively identified, possible skeletal remains have been attributed to Earhart. The partial skeleton recovered and investigated by British officials in 1940. Their investigation concluded the remains were those of a stocky, middle-aged male. A private historic group re- evaluated the British analysis in 1998 as part of research to establish Gardner (Nikumaroro) Island as the crash site. The 1998 report discredited the British conclusions and used cranial analysis software (FORDISC) results to suggest the skeleton was potentially a Northern European woman, and consistent with Amelia Earhart. -

Bones, Chalk and Cheese

Bones, Chalk and Cheese The pilot of the series Bones, from 2005, is a clear example of two characters who not only have distinctive voices, but are from different metaphorical planets. The show proved to be extremely successful and durable for Fox; it ran for twelve seasons, ending in 2017. When Booth (David Boreanaz) and Brennan (Emily Deschanel) talk to each other, it’s clear that one is from Mars and the other from Venus—but the stereotypical roles have been reversed. Brennan is scientific and technical; she has no idea about anything to do with pop culture at all. He’s exactly the opposite. I remember watching the excellent pilot (written by Hart Hanson, the showrunner) and noticing that whenever anybody says something that has any reference to pop culture, Brennan says, “I don't know what that means.” It’s a brilliant, deadpan catch phrase, and what’s fun about it is that she really doesn’t. She is so hyper-focused on being a forensic anthropologist that it’s all she really knows. She’s not connected to her emotional life and doesn’t understand humor —there’s an element of her that’s almost autistic. She lives in the world yet doesn’t really notice and participate in slang and cultural references as most of us tend to do. So Brennan’s distinctive voice is out of step and out of time. !1 Brennan and Booth are also out of step with each other—although she doesn't understand pop culture, he does. He’s street smart and has a lot of bravado and swagger, and she’s restrained, scientific and kind of emotionally shut down. -

Bioterrorism and Weapons of Mass Destruction

NV: Bioterrorism and Weapons of Mass Destruction Author: Susan Walters Schmid, PhD Contact hours: 4 Course price: $39 Instructions 1. To print everything you need, including the test, evaluation, and registration, click Print This Page at the top right. Study the course, pass the test, and fill out the forms. 2. Make out your check or money order to ATrain Education, Inc. Or enter your credit card information on the form provided. 3. Mail the completed forms with your payment to: ATrain Education, Inc 5171 Ridgewood Rd Willits, CA 95490 When we receive your order, we will grade your test, process your payment, and email a copy of your certificate. For a paper copy of your certificate (suitable for framing), please add $8.50 to your payment. Questions? Call 707 459-1315 (Pacific Time) or email ([email protected]). This course fulfills the bioterrorism continuing education requirement for all nurses licensed or seeking licensure in Nevada. It is not approved and does not fulfill the bioterrorism CE requirement for physicians or physician assistants. Course Summary Defines terrorism, bioterrorism, and weapons of mass destruction and summarizes the diseases and agents most commonly used as chemical, biological, radiologic, and nuclear weapons. Outlines CDC recommendations and best practices and discusses the components and use of the Nevada Health Alert Network (HAN). COI Support Accredited status does not imply endorsement by ATrain Education or any accrediting agency of any products discussed or displayed in this course. The planners and authors of this course have declared no conflict of interest and all information is provided fairly and without bias. -

The Temperence Brennan Series by Kathy Reichs

The Temperence Brennan Series by Kathy Reichs Deja Dead [1997] body part that doesn't match up with the remains of any of the plane's passengers. The leg she grabs out of the When the bones of a woman are discovered jaws of a coyote feeding on the carnage scattered around in the grounds of an abandoned monastery, the site belongs to an unidentified elderly man, and Dr Temperance Brennan of the Laboratoire seems to have no connection with the disaster. But an de Medecine Legale in Montreal is convinced abandoned hunting lodge near the crash site does, that a serial killer is at work. The detective in charge of although before Tempe can figure out exactly how they're the case disagrees with her, but he is forced to revise his linked, she's pulled off the DMORT unit and forced to opinion. stand idly by as her professional reputation goes up in flames. When Andrew Ryan, a detective familiar to readers of Kathy Reichs's earlier books (Deja Dead, Death Death du Jour [1999] du Jour, Deadly Decisions), appears on the scene, another mystery begins to unfold. There seems to be no trace of March in Montreal: It is a bitterly cold night two men on the plane's manifest, Ryan's partner and his and in the grounds of an old church forensic seatmate, a criminal who was being escorted back to anthropologist Dr Temperance Brennan digs Canada via Washington, D.C., the doomed flight's final carefully. She is there to exhume the remains of a nun destination, to stand trial for murder.