The Devil Is in the Details: Will the Campus Save Act Provide More Or Less Protection to Victims of Campus Assaults?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clery Act Hierarchy Following the Final Rules Implementing the Violence Against Women Act

Clery Act Hierarchy Following the Final Rules Implementing the Violence Against Women Act I- Clery Reportable Crimes, Incidents, Arrests & Referrals Following upon publication of the Final Rules implementing the Clery Act changes to the Violence Against Women Act, the following categories of crimes are reportable when the crime occurs within Clery Geography (On Campus, On Campus Residential, Non Campus and Public Property Adjacent to and Accessible from On Campus property): Part I Primary Crimes (A) Criminal homicide: (1) Murder and non-negligent manslaughter, and (2) Negligent manslaughter. (B) Sex offenses: (1) Rape, (2) Fondling, (3) Incest, and (4) Statutory rape. (C) Robbery. (D) Aggravated assault. (E) Burglary. (F) Motor vehicle theft. (G) Arson. Part II Drug Alcohol and Weapons Arrests & Referrals for Discipline (A) Weapons arrests. (B) Drug law arrests (C) Liquor law arrests (D) Weapons law referrals (E) Drug law referrals (F) Liquor law referrals Part III Hate Crimes- NARRATIVE FORMAT (Narrative format is advised over a table, but you may use a table that re-lists all Part I Primary crimes, plus the four Hate Crime only crimes) Part IV VAWA Crimes (A) Domestic violence. (B) Dating Violence. (C) Stalking. II- Hierarchy Counting and Classifying Rules The Hierarchy Rule states that when counting more than one crime that occurs in a single transaction, we subsume lesser crimes into the gravest crime, and only count the gravest crime. Exceptions to the Hierarchy Rule include the following: • Crimes that occur in on campus residence halls are counted twice, once On Campus and once On Campus Residential. • Arson is always counted and is not subsumed into graver crimes. -

The Clery Act: Fast Facts

The Clery Act: Fast Facts The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crimes Statistics Act (the Clery Act) is a federal consumer protection law, enforced by the Clery Compliance Team within the Department of Education’s Financial Aid Division. The Clery Act provides guidelines and expectations for campus crime classification and reporting, crime prevention and response and campus safety policy and procedure requirements that create transparency between institutions of higher education and their students and employees. Institutions of higher education receiving History federal financial aid under Title IV are Jeanne Clery was a first required to fully comply with the Clery year student at Lehigh Act. The Clery Act requires institutions to University in April 1986 complete certain annual and ongoing tasks. when she was raped Each year, by October 1st, institutions must and murdered in her publish an annual security report containing dorm room. Her parents, policy statements, summaries of various Howard and Connie campus safety policies and procedures, and Clery, worked tirelessly Clery crime statistics. at the local, state and national level to craft Some examples of campus safety topics legislation that became covered in the policy statements include: what we know today • to whom to report crimes as the Clery Act. The • the law enforcement authority and Clerys also founded jurisdiction of campus security or police the non-profit training • procedures to follow in the event organization known of sexual assault, dating violence, today as Clery Center. domestic violence or stalking • drug and alcohol policies and prevention programs and, • for institutions with on-campus student housing, missing student notification procedures and fire safety procedures. -

Violence Against Women Act, Clery Act, & Title IX

Violence Against Women Act, Clery Act, & Title IX How the Campus SAVE provision affects all three bodies of law. Title IX – Enacted in 1972 as part of larger educational package by the federal government. Pertinent provision requires that no person, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. Because the language of the law is very brief and raised more questions than it answered, then President Nixon assigned the Dept. of Education to be in charge of resolving questions and giving schools guidance on how to comply. The Dept. of Education occasionally issues directives or letters to schools providing them with guidance. One of these letters was published in 2011 and is known as the “Dear Colleague Letter” (DCL) and it specifically stated that the requirements of Title IX cover sexual violence and reminded schools of their responsibilities to take immediate and effective steps to respond. • Title IX applies only to institutions of higher education. Clery Act - Enacted in 1990 to require all schools receiving federal monies to collect and publish information about crime occurring on campus. Schools must publish a yearly report of all crimes reported and must immediately notify students of any reported attacks when they occur on campus. Federal law definitions (and NOT the state of Texas penal code) determines what constitutes a crime. • The Clery Act applies only to institutions of higher education. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) – Enacted in 1994 to raise awareness of domestic violence and assault crimes against women. -

Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS/M ASSOCIATED THE AR Y AL Y ta FF ER Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill Anthony Green and Donna Cooper April 2012 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Auditing the Cost of the Virginia Tech Massacre How Much We Pay When Killers Kill Anthony Green and Donna Cooper April 2012 Remembering those we lost The Center for American Progress opens this report with our thoughts and prayers for the 32 men and women who died on April 16, 2007, on the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg, Virginia. We light a candle in their memory. Let the loss of those indispensable lives allow us to examine ways to prevent similar tragedies. — Center for American Progress Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Determining the cost of the Virginia Tech massacre 7 Virginia Tech’s costs 14 Commonwealth of Virginia’s costs 16 U.S. government costs 17 Health care costs 19 What can we learn from spree killings? 24 Analysis of the background check system that failed Virginia Tech 29 Policy recommendations 36 The way forward 38 About the authors and acknowledgements 39 Appendix A: Mental history of Seung-Hui Cho 45 Appendix B: Brief descriptions of spree killings, 1984–2012 48 Endnotes Introduction and summary Five years ago, on April 16, 2007, an English major at Virginia Tech University named Seung-Hui Cho gunned down and killed 32 people, wounded another 17, and then committed suicide as the police closed in on him on that cold, bloody Monday. Since then, 12 more spree killings have claimed the lives of another 90 random victims and wounded another 92 people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time when deranged and well-armed killers suddenly burst upon their daily lives. -

University of California, Irvine

University of California, Irvine )HGHUDOClery Act Crime Offense Definitions Part 1 Crimes Murder1RQ1HJOLJHQW0DQVODXJKWHU: The willful killing of RQHKXPDQEHLQJE\DQRWKHU. 1HJOLJHQWManslaughter: The killing of another person through gross negligence. Sex Offenses: Any sexual act directed against another person, without consent of the victim including instances where the victim is incapable of giving consent. This definition includes male and female victims. a. 5DSH 3HQHWUDWLRQQRPDWWHUKRZVOLJKWRIWKHYDJLQDRUDQXVZLWKDQ\ERG\SDUWRUREMHFWRURUDOSHQHWUDWLRQE\DVH[RUJDQRIDQRWKHUSHUVRQZLWKRXW WKHFRQVHQWRIWKHYLFWLPLQFOXGLQJZKHQWKHYLFWLPLVLQFDSDEOHRIJLYLQJFRQVHQWEHFDXVHRIWHPSRUDU\RUSHUPDQHQWPHQWDOSK\VLFDOLQFDSDFLW\7KLV GHILQLWLRQLQFOXGHVDQ\JHQGHURIYLFWLPRUSHUSHWUDWRU7KLVGHILQLWLRQRI5DSHQRZLQFOXGHV6RGRP\DQG6H[XDO$VVDXOWZLWKDQ2EMHFWGHILQLWLRQV b. )RQGOLQJ 7KHWRXFKLQJRIWKHSULYDWHERG\SDUWVRIDQRWKHUSHUVRQIRUWKHSXUSRVHRIVH[XDOJUDWLILFDWLRQZLWKRXWFRQVHQWRIWKHYLFWLPLQFOXGLQJLQVWDQFHVZKHUH c. WKHYLFWLPLVLQFDSDEOHRIJLYLQJFRQVHQWEHFDXVHRIKLVKHUDJHRUWHPSRUDU\RUSHUPDQHQWPHQWDORUSK\VLFDOLQFDSDFLW\ ,QFHVW1RQIRUFLEOHVH[XDOLQWHUFRXUVHEHWZHHQSHUVRQVZKRDUHUHODWHGWRHDFKRWKHUZLWKLQWKHGHJUHHVZKHUHLQPDUULDJHLVSURKLELWHGE\ODZ G. 6WDWXWRU\5DSH1RQIRUFLEOHVH[XDOLQWHUFRXUVHZLWKDSHUVRQZKRLVXQGHUWKHVWDWXWRU\DJHRIFRQVHQW Robbery: 7KHWDNLQJRUDWWHPSWLQJWRWDNHDQ\WKLQJRIYDOXHIURPWKHFDUHFXVWRG\RUFRQWURORIDSHUVRQRUSHUVRQVE\IRUFHRUWKUHDWRIIRUFHRU YLROHQFHDQGRUE\SXWWLQJWKHYLFWLPLQIHDU LQFOXHVDWWHPSWV Aggravated Assault: An XQODZIXODWWDFNE\RQHSHUVRQXSRQDQRWKHUIRUWKHSXUSRVHRILQIOLFWLQJVHYHUHRUDJJUDYDWHGERGLO\LQMXU\ -

Final Program Review Determination

December 9, 2010 Charles W. Steger, Ph.D. President Overnight Mail Virginia Polytechnic Institute & Sll!te University Tracking Number 222 Burrus Hall lZ A5467YOl 97995015 Blapksburg, VA 24061 RE: FiDaIProgram.Review.~terminatioD (FPRD) OPE 1D:00375400 PRCN: 200810326735 Dear Dr. Steger: The U.S. Department of Education's (Department's) School Participation Team - Philadelphia issued a program review report on January 21, 2010 regarding Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University's (Virginia Tech's; the University's) administration of programs authori2:ed pursuant to Title IV ofthe Higher Ed1.lcationAct of 1965,85 amended, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1070 et~. (Title IV, HEA programs). This program review focUsed on Virginia Tech's complill!lce willi theJeanneClery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act (Clery Act). Virginia Tech's final response wasreceived on April 2 1,2010. TheFinaI Program Detennination Letter (FPRD) is enclosed. Copies ofthe program review report, the Revised Timeline of EventS contained in theGovemor'sReviewPanel Report, and Virginia Tech's response are also enclosed. Any supporting documentation submitted with .Vlrginia Tech's response is being retained by the Department and is available for inspection by Virginia Tech upon request. AdditionaUy, this FPRD, rel;ited attachments, and any supporting documentation are public documents and may be provided to other oversight entities after the FPRD is issued. Purpose: A final detennination has been made concerning the outstanding filldings of the program review report and is. detailed in the attached FPRD. The purpose of this letter is to: 1) advise the University of the Department's final detenninatioll and 2) to notify Virginia Tech ofapossible adverse administrative action. -

Title IX the Clery Act

This document was created by the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, April 2014 Intersection of Title IX and the Clery Act The purpose of this chart is to clarify the reporting requirements of Title IX and the Clery Act in cases of sexual violence and to resolve any concerns about apparent conflicts between the two laws. To date, the Department of Education has not identified any specific conflicts between Title IX and the Clery Act. Title IX The Clery Act What types of incidents must be reported to school officials under Title IX and the Clery Act? Overview: Title IX promotes equal opportunity by providing that no person Overview: The Clery Act promotes campus safety by ensuring that students, may be subjected to discrimination on the basis of sex under any educational employees, parents, and the broader community are well-informed about program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. A school must important public safety and crime prevention matters. Institutions that respond promptly and effectively to sexual harassment, including sexual receive Title IV funds must disclose accurate and complete crime statistics for violence, that creates a hostile environment. When responsible employees incidents that are reported to Campus Security Authorities (CSAs) and local law know or should know about possible sexual harassment or sexual violence they enforcement as having occurred on or near the campus. Schools must also must report it to the Title IX coordinator or other school designee. disclose campus safety policies and procedures that specifically address topic Sexual Harassment: Sexual harassment is unwelcome conduct of a sexual such as sexual assault prevention, drug and alcohol abuse prevention, and nature, including unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, emergency response and evacuation. -

CLASSIFYING HATE CRIMES Under the Clery Act

9/26/2018 CLASSIFYING HATE CRIMES Under the Clery Act TODAY’S PRESENTERS Dr. John Wesley Lowery Laura Egan Department Chairperson and Senior Director of Programs Graduate Coordinator Department of Student Affairs in Higher Education Indiana University of Pennsylvania #NCSAM18 | 2 CLERY CENTER: MISSION AND VALUES Values and Distinguishing Mission Statement Characteristics Working together with college • We honor our organization’s history and university communities to by leading with mind and heart. • We are collaborative and pursue create safer campuses. strong partnerships that are based on joint success and open, constructive communication. • We believe that prevention is critical to campus safety. • We are persistent, action-oriented, and deliver results that have real impact. #NCSAM18 | 3 1 9/26/2018 JEANNE ANN CLERY #NCSAM18 | 4 NCSAM 2018: WHAT’S YOUR MESSAGE? • Commit to year-round work that examines effectiveness of messages about campus safety. • Visit ncsam.clerycenter.org to review all resources provided this month including recorded webinars and resources available for download. • Looking ahead to next year: what should NCSAM 2019’s focus be? #NCSAM18 | 5 KEY RESOURCES • The Clery Act – Statute and Regulations • The Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reporting • Westat • [email protected] • 800-435-5985 • ED Program Review Findings #NCSAM18 | 6 2 9/26/2018 TODAY’S GOALS • Review how hate crimes are defined and classified under the Clery Act • Explore how incidents might be violations of policy but not a Clery -

CLERY REPORTABLE CRIME DEFINITIONS: Aggravated Assault

CLERY REPORTABLE CRIME DEFINITIONS: Aggravated Assault: An unlawful attack by one person upon another for the purpose of inflicting severe or aggravated bodily injury. This type of assault usually is accompanied by the use of a weapon or by means likely to produce death or great bodily harm. It is not necessary that injury result from an aggravated assault when a gun, knife or other weapon is used which could or probably would result in a serious potential injury if the crime were successfully completed. The following would be classified as aggravated assaults: assaults or attempts to kill or murder, poisoning (including the use of date rape drugs), assault with a dangerous or deadly weapon, maiming, mayhem, assault with explosives, or assault with a disease. Arson: The willful or malicious burning or attempt to burn, with or without intent to defraud, a dwelling house, public building, motor vehicle or aircraft, or personal property of another, etc. Burglary: The unlawful entry of a structure to commit a felony or a theft. For reporting purposes this definition includes: unlawful entry with intent to commit a larceny or a felony; breaking and entering with intent to commit a larceny; housebreaking; safecracking; and all attempts to commit any of the aforementioned. Dating Violence: The term “dating violence” means violence committed by a person who is or has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim. The existence of such a relationship shall be determined based on the reporting party’s statement and with consideration of the length of the relationship, the type of relationship, and the frequency of interaction between the persons involved in the relationship. -

Clery Act Guidelines for Campus Security Authorities - Clery Crime Definitions

Clery Act Guidelines for Campus Security Authorities - Clery Crime Definitions Criminal Offenses Murder and Non-Negligent Manslaughter: The willful (non-negligent) killing of one human being by another. Manslaughter by Negligence: The killing of another person through gross negligence. Sexual Assault: An offense that meets the definition of rape, fondling, incest or statutory rape as used in the FBl's Uniform Crime Reporting system. A sex offense is any sexual act directed against another person, without the consent of the victim, including instances where the victim is incapable of giving consent. Rape: The penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim. Fondling: The touching of the private body parts of another person for the purpose of sexual gratification, without the consent of the victim, including instances where the victim is incapable of giving consent because of his/her age or because of his/her temporary or permanent mental incapacity. Incest: Sexual intercourse between persons who are related to each other within the degrees wherein marriage is prohibited by law. Statutory Rape: Sexual intercourse with a person who is under the statutory age of consent. Sexual assault is defined in the Texas Penal Code, Chapter 22, Section 22.011. Robbery: The taking or attempting to take anything of value from the care, custody, or control of a person or persons by force or threat of force or violence and/or by putting the victim in fear. Aggravated Assault: An unlawful attack by one person upon another with the purpose of inflicting severe or aggravated bodily injury. -

Timely Warnings & Sexual Assault: Building an Effective and Consistent Approach Abigail Boyer | Clery Center Joseph Storch |

Timely Warnings & Sexual Assault: Building an Effective and Consistent Approach Abigail Boyer | Clery Center Joseph Storch | SUNY System The Clery Center Jeanne Clery Act: A History Changing the Landscape • History of Campus Safety • Connie & Howard Clery • Parents • Co-founders, Security On Campus (SOC) • Legislation (state, federal) • Advocacy • Awareness raising • Impact Agenda •Timely Warning & Emergency Notification Overview • Mythbusting • Lesson Learned: Program Reviews • Activity Timely Warning Overview Background Knowledge On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate your understanding of the requirements of the Jeanne Clery Act specific to timely warnings? 1-2: Novice 3-4: Some familiarity 5-6: Competence 7-8: Mastery 9-10: Expert Jeanne Clery Act: Overview Annual Security Report •Policy statements •Campus crime statistics •Campus Sexual Assault Victims’ Bill of Rights Ongoing Disclosures •Emergency notification •Timely warning •Public crime log U.S. Department of Education (ED) Enforces Jeanne Clery Act: Overview Violence Against Women Act Clery Act Crimes Amendments to the Clery Act • Homicide •Dating Violence •Sex Offenses •Domestic Violence • Robbery • Stalking •Aggravated Assault • Burglary Arrests & Disciplinary Referrals •Motor Vehicle Theft •Liquor law violations • Arson •Drug law violations •Hate crimes •Illegal weapons possession Who is a CSA? •Officials with significant responsibility for student and campus activities •A campus police or a campus security department • Individuals or offices designated to receive crime reports -

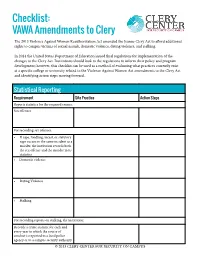

Checklist: VAWA Amendments to Clery

Checklist: VAWA Amendments to Clery The 2013 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act amended the Jeanne Clery Act to afford additional rights to campus victims of sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking. In 2014 the United States Department of Education issued final regulations for implementation of the changes to the Clery Act. Institutions should look to the regulations to inform their policy and program development; however, this checklist can be used as a method of evaluating what practices currently exist at a specific college or university related to the Violence Against Women Act amendments to the Clery Act and identifying action steps moving forward. Statistical Reporting Requirement Site Practice Action Steps Reports statistics for the required crimes: Sex offenses For recording sex offenses: • If rape, fondling, incest, or statutory rape occurs in the same incident as a murder, the institution records both the sex offense and the murder in its statistics • Domestic violence • Dating Violence • Stalking For recording reports on stalking, the institution: Records a crime statistic for each and every year in which the course of conduct is reported to a local police agency or to a campus security authority © 2013 CLERY CENTER FOR SECURITY ON CAMPUS Statistical Reporting Requirement Site Practice Action Steps For recording reports of stalking, the institution: Records each report of stalking as occurring only at the first location within the institution’s Clery geography in which a perpetrator engaged in