2016/17 Knowledge Sharing Program with Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Report on Ihp Related Activities

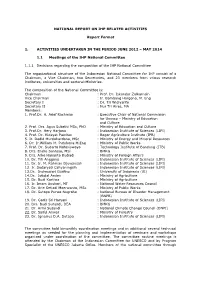

NATIONAL REPORT ON IHP RELATED ACTIVITIES Report Format 1. ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN IN THE PERIOD JUNE 2012 – MAY 2014 1.1 Meetings of the IHP National Committee 1.1.1 Decisions regarding the composition of the IHP National Committee The organizational structure of the Indonesian National Committee for IHP consist of a Chairman, a Vice Chairman, two Secretaries, and 23 members from vrious research institutes, universities and sectoral-Ministries. The composition of the National Committee is: Chairman : Prof. Dr. Iskandar Zulkarnain Vice Chairman : Ir. Bambang Hargono, M. Eng Secretary I : Dr. Tri Widiyanto Secretary II : Nur Tri Aires, MA Members: 1. Prof.Dr. H. Arief Rachman : Executive Chair of National Commision for Unesco – Ministry of Education and Culture 2. Prof. Drs. Agus Subekti MSc, PhD : Ministry of Education and Culture 3. Prof.Dr. Hery Harjono : Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 4. Prof. Dr. Hidayat Pawitan : Bogor Agriculture Institute (IPB) 5. Ir. Dodid Murdohardono, MSc : Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources 6. Dr. Ir.William M. Putuhena M.Eng : Ministry of Public Works 7. Prof. Dr. Sudarto Notosiswoyo : Technology Institute of Bandung (ITB) 8. Drs. Endro Santoso, MSi : BMKG 9. Drs. Arko Hananto Budiadi : Ministry of Foreign Affairs 10. Dr. Titi Anggono : Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 11. Dr. Ir. M. Rahman Djuwansah : Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 12. Ir. Sudaryati Cahyaningsih : Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 13.Dr. Indreswari Guritno : University of Indonesia (UI) 14.Dr. Istiqlal Amien : Ministry of Agriculture 15. Dr. Budi Kartiwa : Ministry of Agriculture 16. Ir. Imam Anshori, MT : National Water Resources Council 17. Dr. Arie Setiadi Moerwanto, MSc : Ministry of Public Works 18. -

Corruption in Indonesian Local Government: Study on Triangle Fraud Theory

International Journal of Business and Society, Vol. 19 No. 2, 2018, 536-552 CORRUPTION IN INDONESIAN LOCAL GOVERNMENT: STUDY ON TRIANGLE FRAUD THEORY Muhtar Universitas Sebelas Maret Sutaryo. Universitas Sebelas Maret Sriyanto Universitas Sebelas Maret dan Badan Pengawasan Keuangan dan Pembangunan (BPKP) ABSTRACT The paper examines the effect of performance accountability, regional income, e-government, internal audit capabilities, audit responses, and public officials wage on corruption in local government using fraud triangle theory framework. The increasingly widespread corruption cases even though abundance of government’s programs have been done to overcome them, let this research seeks to answer whether government’s priority programs are aligned with corruption eradication strategy. This paper uses local government panel data in Indonesia from 2010 to 2013 analyzed using multiple linear regression method. The result shows that performance accountability and public official wage have negative effect on corruption, while audit responses have positive effect on corruption. On the other hand, regional income, e-government, and internal audit capabilities show no evidence on effect on corruption. This finding is fairly robust in separate analysis on municipalities and local government outside Sumatra and Java. This paper provides empirical evidence that audit responses can detect corruption whereas performance accountability and the increase in regional income increases can contribute to curbing corruption. Keywords: Audit response; Corruption; E-government, Fraud triangle, Local government; Performance accountability. 1. INTRODUCTION Corruption is one of big problems in world economy in 2016. This case covers 35% of all frauds on job and inflict economic loss of Rp 2.7 billion in average (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners/ACFE, 2016). -

Indonesia Anti- Corruption Agency 2015-2016

ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCY STRENGTHENING INITIATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE INDONESIA ANTI- CORRUPTION AGENCY 2015-2016 Transparency International is the global civil society organization leading the fight against corruption. Through more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we raise awareness of the damaging effects of corruption and work with partners in government, business and civil society to develop and implement effective measures to tackle it. www.transparency.org Author: xxx Contributions: xxx Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of 2017. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. Transparency International would like to thank the Anti-Corruption Agency of Indonesia for their cooperation and support in conducting this assessment. This publication reflects the views of the author and contributors only, and the Anti-Corruption Commission of Indonesia cannot be held responsible for the views expressed or for any use which may be made of the information contained herein. ISBN: 978-3-943497-57-1 Printed on 100% recycled paper © 2017 Transparency International. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................... -

Determinants of Labor Migration in Overseas in Indonesia

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 12 (2018)pp.:37-41 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Determinants of Labor Migration in Overseas in Indonesia *Nurhuda, *Madris, *Fatmawati (Post Graduate Masters in Resource Economics, Hasanuddin University) (Lecturer at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Postgraduate School, Hasanuddin University) (Lecturer at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Postgraduate School, Hasanuddin University) Corresponding Author: Nurhuda ABSTRACT: This study tries to look at the effect of the Young Dependency Ratio, provincial minimum wages and the quality of human resources on migrant migrant workers abroad labor force ratios through employment in 15 provinces in Indonesia with the largest TKI delivery rates to overseas. The analysis technique used in this study is the Structural Equation Model (SEM), to see the direct and indirect relationship between the dependent and independent variables and the intervening variable, namely labor absorption. From the results of the analysis, it was found that the Young Dependency Ratio directly affected migrant workers' migrations abroad, while the ratio of temporary labor force through employment was not influential. Variable provincial minimum wages directly do not affect migration of migrant workers abroad, while indirectly through influential employment. The quality of human resources, both directly and indirectly through the absorption of labor influences the migration of migrant workers abroad. Keywords: YDR, Provincial Minimum Wages, Quality of Human Resources, Absorption of Labor, Migration of Indonesian Migrant Workers Abroad Received 14 December, 2018; Accepted 31 December, 2018 © the Author(S) 2018. Published With Open Access At www.Questjournals.Org. -

What Affects Audit Delay in Indonesia?

Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal Volume 27, Special Issue 2, 2021 WHAT AFFECTS AUDIT DELAY IN INDONESIA? Indra Prasetyo, Universitas Wijaya Putra Nabilah Aliyyah, Universitas Wijaya Putra Rusdiyanto, Universitas Airlangga Diah Rani Nartasari, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Sanjayanto Nugroho, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Yessi Rahmawati, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Selvi Permata Groda, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Surya Setiawan, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Bigraf Triangga, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Eko Mailansa, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Gusti Dian Prayogi, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Niki Etruly, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Muhamad Jazuli, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Nila Dewi Wahyuningsih, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Nunik Dwi Kusumawati, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Satunggale Kurniawan, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Indira Nuansa Ratri, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Wiyono Atmojo, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Yuventius Sugiarno, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Danny Koerniawan Pamungkas, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Ahmad Muslim, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Muhammad Afifi Rahman, Akademi Sekretari dan Manajemen Indonesia Surabaya Nawang -

A Report on Training on the 2016 Economic Census of Indonesia

A REPORT ON TRAINING ON THE 2016 ECONOMIC CENSUS OF INDONESIA ORGANISED BY BADAN PUSAT STATISTIK (BPS) INDONESIA FROM OCTOBER 10-14 2016 UNDER THE PROJECT ON CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT FOR ECONOMIC CENSUS 2018 OF NEPAL WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)-Nepal Coordinated and Cooperated by JICA-Indonesia SUBMITTED BY Anil SHARMA Rajesh DHITAL & Mahesh Chand PRADHAN (DIRECTORs) Economic Census 2018-Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, NEPAL 1 Acknowledgement First of all, on behalf of the Central Bureau of Statistics-Nepal, particularly the team of delegates, we would like to express our sincere appreciation to JICA in Nepal for having good arrangement of making technical exchange with the Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) of Indonesia and training on the 2016 Economic Census of Indonesia in relation to the capacity development program for the Economic Census 2018 of Nepal. It was a good opportunity to visit, learn about the Economic Census 2016-round planning, preparation, methods, statistical infrastructure and implementation, enumeration mapping and its fieldwork, data quality assurance, data processing and data dissemination. Also we are grateful to BPS for wonderful arrangement of training and sharing the experiences about the ongoing Economic Census 2016 in Indonesia. We are equally grateful to JICA-Indonesia for cooperating and coordinating the event in Jakarta. We are indebted to Central Bureau of Statistics Nepal for giving the opportunity for the capacity development in implementing the Economic Census for the first time in Nepal. On behalf of CBS team, we would appreciate Mr. Fumihiko Nishi for his hard and dedicated efforts in facilitating this training for capacity development. -

Talent Management Based-Education: Indonesian Case

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 11 No 3 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org May 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Winingsih et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 21 January 2020 / Revised: 30 April 2020 / Accepted: 1 May 2020 / Published: 10 May 2020 Talent Management Based-Education: Indonesian Case Lucia H Winingsih Iskandar Agung Agus Amin Sulistiono Center for Research of Education and Culture, Research and Development and Books Agency, MOEC, Jln. Jend. Sudirman, Senayan, Building E-19 Fl, Central Jakarta, Indonesia Doi: 10.36941/mjss-2020-0032 Abstract This study aims to determine the effect variables on the implementation of talent management of based education (TMBE). The paper is part of the results study in 3 (three) cities in DKI Jakarta, Banten, West Java Province, Republic of Indonesia with a sample of three senior high schools each taken by purposive technique, especially good criteria and have teacher guidance and counseling status. From each school 20 high school teachers were randomly drawn to answer the questionnaire distributed to them. The questionnaire was previously validated and reliable using the product moment test criteria from Pearson and Cronbach Alpha with the help of the SPSS program version 24.0. Data is processed and analyzed using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach using the Lisrel 8.70 program. The study resulted that the provincial government policy variables (PDS), school conditions (SC), teaching activities (LT), teacher guidance and counseling (GC) functions, and parent participation (PP) had a direct positive effect on the TMBE, Cultural Values (CV), and National Education (NE) variables. -

Sustainable Ocean Economy Country Diagnostics of Indonesia

Sustainable Ocean for All Series SUSTAINABLE OCEAN ECONOMY COUNTRY DIAGNOSTICS OF INDONESIA Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development DCD(2021)5 Unclassified English text only 20 April 2021 DEVELOPMENT CO-OPERATION DIRECTORATE Sustainable Ocean Economy Country Diagnostics of Indonesia April 2021 This document is submitted for INFORMATION. For more information on Sustainable Ocean Economy see https://www.oecd.org/ocean/topics/developing-countries-and-the-ocean-economy/ Contacts: Piera Tortora, [email protected] Alberto Agnelli, [email protected] JT03475041 OFDE This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. DCD(2021)5 | 3 Abstract Indonesia is located in one of the world’s richest regions in terms of ocean resources, as well as one of the most affected ones from increasing pollution and degradation of marine ecosystems. Ocean-based sectors - such as fisheries, marine aquaculture and tourism - have contributed to the country’s economic dynamism over the past two decades. The impacts from COVID-19, however, are laying bare the need for Indonesia to enhance the resilience and sustainability of its ocean-based sectors as a way to set more solidly on a path of sustainable and inclusive development. This Sustainable Ocean Economy Country Diagnostics of Indonesia provides a compass for understanding the complexity of Indonesia’s ocean economy and for enhancing the economic, social, and environmental benefits from a more sustainable ocean economy. It focusses on three analytical pillars: (i) Economic trends of Indonesia’s ocean economy; (ii) Governance frameworks and policy tools to foster a more sustainable ocean economy; and (iii) Financing instruments and flows, with a focus on development finance. -

Comparison of Tobacco Import and Tobacco

Ahsan et al. Globalization and Health (2020) 16:65 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00595-y RESEARCH Open Access Comparison of tobacco import and tobacco control in five countries: lessons learned for Indonesia Abdillah Ahsan1* , Nur Hadi Wiyono1, Meita Veruswati2, Nadhila Adani1, Dian Kusuma3 and Nadira Amalia4 Abstract Background: With a 264 million population and the second highest male smoking prevalence in the world, Indonesia hosted over 60 million smokers in 2018. However, the government still has not ratified the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. In the meantime, tobacco import increases rapidly in Indonesia. These create a double, public health and economic burden for Indonesia’s welfare. Objective: Our study analyzed the trend of tobacco import in five countries: Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. Also, we analyze the tobacco control policies implemented in these countries and determine some lessons learn for Indonesia. Methods: We conducted quantitative analyses on tobacco production, consumption, export, and import during 1990–2016 in the five countries. Data were analyzed using simple ordinary least square regressions, correcting for time series autocorrelation. We also conducted a desk review on the tobacco control policies implemented in the five countries. Results: While local production decreased by almost 20% during 1990–2016, the proportion of tobacco imports out of domestic production quadrupled from 17 to 65%. Similarly, the ratio of tobacco imports to exports reversed from 0.7 (i.e., exports were higher) to 2.9 (i.e., import were 2.9 times higher than export) in 1990 and 2016, respectively. This condition is quite different from the other four respective countries in the observation where their tobacco export is higher than the import. -

Annual Oil Palm Plantation Maps in Malaysia and Indonesia from 2001 to 2016

Discussions https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2019-137 Earth System Preprint. Discussion started: 7 October 2019 Science c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Open Access Open Data Annual oil palm plantation maps in Malaysia and Indonesia from 2001 to 2016 Yidi Xu1, Le Yu1,2*, Wei Li1, Philippe Ciais3, Yuqi Cheng1, Peng Gong1,2 1Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Earth System Modeling, Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua 5 University, Beijing, 100084, China 2Joint Center for Global Change Studies, Beijing 100875, China 3Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE/IPSL, CEA-CNRS-UVSQ, Universite Paris-Saclay, Gif- sur-Yvette 91191, France 10 Correspondence to: Le Yu ([email protected]) Abstract. Increasing global demand of vegetable oils and biofuels results in significant oil palm expansion in Southeast Asia, predominately in Malaysia and Indonesia. The land conversion to oil palm plantations leads to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and greenhouse gas emission over the past decades. Quantifying the consequences of oil palm expansion requires fine scale and frequently updated datasets of land cover dynamics. Previous studies focused on total changes for a multi-year 15 interval without identifying the exact time of conversion, causing uncertainty in the timing of carbon emission estimates from land cover change. Using Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) Phased Array Type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR), ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) datasets, we produced an Annual Oil Palm Area Dataset (AOPD) at 100-meter resolution in Malaysia and Indonesia from 2001 to 2016. We first mapped the oil palm extent using PALSAR/PALSAR-2 data for 2007-2010 and 2015-2016 and then applied a disturbance and recovery 20 algorithm (BFAST) to detect land cover change time-points using MODIS data during the years without PALSAR data (2011- 2014 and 2001-2006). -

03247215 Whale Shark Indonesia Project Final Report

Conservation Leadership Programme: Final Report Title Page 1. CLP project ID & Project title: CLP ID03247215 & Whale Shark Indonesia Project 2. Host country, site location and the dates in the field: Indonesia, Talisayan East Kalimantan (August-October 2015), Weh Island Aceh (October-November 2015 & February 2016), Parigi Moutong Central Sulawesi (December 2015-January 2016), Banggai Kepulauan Central Sulawesi (January 2016), Probolinggo East Java (January- March 2016), Botubarani Gorontalo (April 2016), Bolsel North Sulawesi (May 2016). 3. Names of any institutions involved in organising the project or participating: Whale Shark Indonesia Project, Bogor Agricultural University, WWF-Indonesia. 4. The overall aim summarised in 10–15 words: To better understand the distribution, population characteristic and status of whale shark in Indonesia 5. Full names of author(s): Mahardika Rizqi Himawan, Casandra Tania, Sheyka Nugrahani Fadela, Aditya Bramandito. 6. Permanent contact address, email and website: Whale Shark Indonesia Office, Gedung Marine Center Lt. 5, Departemen Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan IPB, Jl. Agathis No. 5 Kampus IPB Darmaga Bogor, Indonesia 16680, [email protected], www.whalesharkindonesia.org. 7. Date which the report was completed: 24 September 2017. The following information should be included in the body of the report: Table of Contents Include a list of contents, with section titles, subtitles and page numbers Section 1 4 Summary 4 Introduction 4 Project members 6 Section 2 7 Aims and Objectives 7 Changes to original project plan 7 Methodology 8 Outputs & Results 9 Communication & Application of results 16 Monitoring and Evaluation 17 Achievements and Impacts 17 Capacity Development and Leadership capabilities 18 Section 3 18 Conclusion 18 Problems encountered and lessons learnt 18 1 In the future 19 Financial Report 20 Section 4 21 CLP M&E measures table 21 Bibliography 29 Project Partners & Collaborators 1. -

Development of Work Plan for Reducing Slcps from MSWM in Surabaya, Indonesia

Development of Work Plan for Reducing SLCPs from MSWM in Surabaya, Indonesia January 2017 1 1. Introduction The Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) is one of the global efforts that unites governments, civil society and private sector, committed to improving air quality and protecting the climate by reducing the Short Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) across different sectors. It was launched on 14 June 2011 by the governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Ghana, Mexico, Sweden and the United States, along with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and currently have 51 national governments, 16 International and Bilateral Agencies and 45 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are working together to address short-lived climate pollutants (SLCP) by raising awareness of short-lived climate pollutant impacts and mitigation strategies, enhancing and developing new national and regional actions, including by identifying and overcoming barriers, increasing capacity, and mobilizing support, promoting best practices and showcasing successful efforts, and improving scientific understanding of short-lived climate pollutant impacts and mitigation strategies1. Under the coalition, 11 initiatives have commenced work thus far. One of these initiatives is the Municipal Solid Waste Initiative (MSWI), aimed at reducing SLCPs created by municipal solid waste. The CCAC-MSWI has completed its Phase 1 (establishment of infrastructure and initial assessment of the MSW initiative) activities and currently underway in Phase II (Implementing on the ground action with cities and informing the long-term framework of the initiative) and Phase III (implement on the ground action with cities towards long-term feasible solutions and scaling up beyond the initial targets). Under this initiative Surabaya, Indonesia undertook a rapid city assessment in 2014.