THE NOATAK RIVER: FALL CARIBOU HUNTING and AIRPLANE USE by Susan Georgette and Hannah Loon Technical Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a List of Material Related to the Gates of the Arctic National Park Resident Zoned Communities Which Are Not Found in the University of Alaska System

This is a list of material related to the Gates of the Arctic National Park resident zoned communities which are not found in the University of Alaska system. This list was compiled in 2008 by park service employees. BOOKS: Douglas, Leonard and Vera Douglas. 2000. Kobuk Human-Land Relationships: Life Histories Volume I. Ambler, Kobuk, Shungnak Woods, Wesley and Josephine Woods. 2000. Kobuk Human-Land Relationships: Life Histories Volume 2. Ambler, Kobuk, Shungnak Kunz, Michael L. 1984. Archeology and History in the Upper Kobuk River Drainage: A Report of Phase I of a Cultural Resources Survey and Inventory. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. Kobuk, Ambler, Shungnak Aigner, Jean S. 1981. Cultural resources at Betty, Etivluk, Galbraith-Mosquito, Itkillik, Kinyksukvik, Swayback, and Tukuto Lakes in the Northern foothills of the Brooks Range, Alaska (incomplete citation, possibly incorrect date). Anaktuvuk Pass Aigner, Jean. 1977. A report on the potential archaeological impact of proposed expansion of the Anaktuvuk Pass airstrip facility by the North Slope Borough. Anaktuvuk Pass Alaska Department of Highways, Planning and Research Division. 1973. City of Huslia, Alaska; population 159. Allakaket, Alaska; population 174. Prepared by the State of Alaska, Department of Highways, Planning and Research Division in cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Allakaket Alexander, Herbert L., Jr. 1968. Archaeology in the Atigun Valley. Expedition 2(1): 35-37. Anaktuvuk Pass Alexander, Herbert L., Jr. 1967. Alaskan survey. Expedition 9(1): 20-29. Anaktuvuk Pass Amsden, Charles W. 1977. Hard times: a case study from northern Alaska, and implications for Arctic prehistory. -

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data

Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data By Carl J. Markon and Sara Wesser Open-File Report 00-51 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey LAND COVER MAPPING OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NORTHWEST ALASKA MANAGEMENT AREA USING LANDSAT MULTISPECTRAL AND THEMATIC MAPPER SATELLITE DATA By Carl J. Markon1 and Sara Wesser2 1 Raytheon SIX Corp., USGS EROS Alaska Field Office, 4230 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4664. E-mail: [email protected]. Work conducted under contract #1434-CR-97-40274 2National Park Service, 2525 Gambell St., Anchorage, AK 99503-2892 Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral Scanner and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data ABSTRACT A land cover map of the National Park Service northwest Alaska management area was produced using digitally processed Landsat data. These and other environmental data were incorporated into a geographic information system to provide baseline information about the nature and extent of resources present in this northwest Alaskan environment. This report details the methodology, depicts vegetation profiles of the surrounding landscape, and describes the different vegetation types mapped. Portions of nine Landsat satellite (multispectral scanner and thematic mapper) scenes were used to produce a land cover map of the Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Noatak National Preserve and to update an existing land cover map of Kobuk Valley National Park Valley National Park. A Bayesian multivariate classifier was applied to the multispectral data sets, followed by the application of ancillary data (elevation, slope, aspect, soils, watersheds, and geology) to enhance the spectral separation of classes into more meaningful vegetation types. -

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the East Central Part of the State, Yukon Flats Is Alaska's Largest Interior Valley

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the east central part of the State, Yukon Flats is Alaska's largest Interior valley. The Yukon River, fifth largest in North America and 2,300 miles long from its source in Canada to its mouth in the Bering Sea, bisects the broad, level flood- plain of Yukon Flats for 290 miles. More than 40,000 shallow lakes and ponds averaging 23 acres each dot the floodplain and more than 25,000 miles of streams traverse the lowland regions. Upland terrain, where lakes are few or absent, is the source of drainage systems im- portant to the perpetuation of the adequate processes and wetland ecology of the Flats. More than 10 major streams, including the Porcupine River with its headwaters in Canada, cross the floodplain before discharging into the Yukon River. Extensive flooding of low- land areas plays a dominant role in the ecology of the river as it is the primary source of water for the many lakes and ponds of the Yukon Flats basin. Summer temperatures are higher than at any other place of com- parable latitude in North America, with temperatures frequently reaching into the 80's. Conversely, the protective mountains which make possible the high summer temperatures create a giant natural frost pocket where winter temperatures approach the coldest of any inhabited area. While the growing season is short, averaging about 80 days, long hours of sunlight produce a rich growth of aquatic vegeta- tion in the lakes and ponds. Soils are underlain with permafrost rang- ing from less than a foot to several feet, which contributes to pond permanence as percolation is slight and loss of water is primarily due to transpiration and evaporation. -

Imikruk Plain

ECOLOGICAL SUBSECTIONS OF KOBUK VALLEY NATIONAL PARK Mapping and Delineation by: David K. Swanson Photographs by: Dave Swanson Alaska Region Inventory and Monitoring Program 2525 Gambell Anchorage, Alaska 99503 Alaska Region Inventory & Monitoring Program 2525 Gambell Street, Anchorage, Alaska 99503 (907) 257-2488 Fax (907) 264-5428 ECOLOGICAL UNITS OF KOBUK VALLEY NATIONAL PARK, ALASKA August, 2001 David K. Swanson National Park Service 201 1st Ave, Doyon Bldg. Fairbanks, AK 99701 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................i Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Ecological Unit Descriptions ........................................................................................................ 3 AFH Akiak Foothills Subsection ............................................................................................ 3 AHW Ahnewetut Wetlands Subsection ................................................................................. 4 AKH Aklumayuak Foothills Subsection ................................................................................. 6 AKM Akiak Mountains Subsection......................................................................................... 8 AKP -

2014 Draft Fisheries Monitoring Plan

2014 Draft Fisheries Monitoring Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 2 Continuation Projects in 2014 ................................................................................................. 7 Technical Review Committee Membership .............................................................................. 8 Technical Review Committee, Regional Advisory Council, and Interagency Staff Committee Recommendations .................................................................................................................. 9 Summary of Regional Advisory Council Recommendations and Rationale .............................. 15 NORTHERN REGION OVERVIEW .................................................................................... 19 14-101 - Unalakleet River Chinook Salmon Assessment Continuation .................................... 25 14-102 - Climate change and subsistence fisheries: quantifying the direct effects of climatic warming on arctic fishes and lake ecosystems using whole-lake manipulations on the Alaska North Slope ........................................................................................................................... 27 14-103 - Dispersal patterns and summer ocean distribution of adult Dolly Varden in the Beaufort Sea using satellite telemetry .................................................................................. -

Annual Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Region, 1987

Fishery Management Report No. 91-1 Annual Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Region, 1987 William D. Arvey, Michael J. Kramer, Jerome E. Hallberg, James F. Parker, and Alfred L. DeCicco April 1991 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish FISHERY MANAGEMENT REPORT NO. 91-1 ANNUAL MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR SPORT FISHERIES IN THE ARCTIC-YUKON-KUSKOKWIM REGION, 1987l William D. Arvey, Michael J. Kramer, Jerome E. Hallberg, James F. Parker, and Alfred L. DeCicco Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish Anchorage, Alaska April 1991 Some of the data included in this report were collected under various jobs of project F-10-3 of the Federal Aid in Fish Restoration Act (16 U.S.C. 777-777K). TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES............................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES.............................................. V LIST OF APPENDICES ........................................... vii ABSTRACT ..................................................... 1 PREFACE...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION................................................. 3 TANANA AREA DESCRIPTION ...................................... 3 Geographic and Geologic Setting ......................... 3 Lake and Stream Development ............................. 10 Climate................................................. 13 Primary Species for Sport Fishing ....................... 13 Status and Harvest Trends of Wild Stocks ................ 13 Chinook Salmon .................................... -

EARLY LIFE HISTORY of CHUM SALMON in the NOATAK RIVER and KOTZEBUE SOUND by Margaret F

EARLY LIFE HISTORY OF CHUM SALMON IN THE NOATAK RIVER AND KOTZEBUE SOUND by Margaret F. Merritt and J.A. Raymond Number 1 EARLY LIFE HISTORY OF CHUM SALMON IN THE NOATAK RIVER AND KOTZEBUE SOUND by Margaret F. Merritt and J.A. Raymond Number 1 Alaska Department of Fish & Game Division of Fisheries Rehabi 1itation Enhancement and Development Don W. Col l'inswort h Acting Commi ssioner Stanley A. Moberly Di rector BOX 3-2000 Juneau, A1 aska 99802 January, 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE LIST OF FIGURES ................................ .............. iii LIST OF TABLES ............................................... iv LIST OF APPENDIX TABLES ...................................... iv ABSTRACT ..................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................. 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS .. ............................... ....... 2 RESULTS ...................................................... 6 Noatak River ............................................ 6 Water Temperatures .................................... 6 Spawning and Development.. Sites 9 and 12.............. 10 Spawning and Development--General .................... 14 Freshwater Feeding .................................. 14 Noatak ~iverWater ~uality............................ 16 1981 Observations ..................................... 16 Kotzebue Sound ...................................... ..... 21 Temperatures and Salinities ........................... 21 Plankton Abundance ................................. 21 Juvenile Chum Salmon -

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health ANTHC Center for Climate and Health Funded by Report prepared by: Michael Brubaker, MS Raj Chavan, PE, PhD ANTHC recognizes all of our technical advisors for this report. Thank you for your support: Gloria Shellabarger, Kiana Tribal Council Mike Black, ANTHC Linda Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Brad Blackstone, ANTHC Dale Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Jay Butler, ANTHC Sharon Dundas, City of Kiana Eric Hanssen, ANTHC Crystal Johnson, City of Kiana Oxcenia O’Domin, ANTHC Brad Reich, City of Kiana Desirae Roehl, ANTHC John Chase, Northwest Arctic Borough Jeff Smith, ANTHC Paul Eaton, Maniilaq Association Mark Spafford, ANTHC Millie Hawley, Maniilaq Association Moses Tcheripanoff, ANTHC Jackie Hill, Maniilaq Association John Warren, ANTHC John Monville, Maniilaq Association Steve Weaver, ANTHC James Berner, ANTHC © Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), October 2011. Funded by United States Indian Health Service Cooperative Agreement No. AN 08-X59 Through adaptation, negative health effects can be prevented. Cover Art: Whale Bone Mask by Larry Adams TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 Introduction 5 Community 7 Climate 9 Air 13 Land 15 Rivers 17 Water 19 Food 23 Conclusion 27 Figures 1. Map of Maniilaq Service Area 6 2. Google Maps view of Kiana and region 8 3. Mean Monthly Temperature Kiana 10 4. Mean Monthly Precipitation Kiana 11 5. Climate Change Health Assessment Findings, Kiana Alaska 28 Appendices A. Kiana Participants/Project Collaborators 29 B. Kiana Climate and Health Web Resources 30 C. General Climate Change Adaptation Guidelines 31 References 32 Rural Arctic communities are vulnerable to climate change and residents seek adaptive strategies that will protect health and health infrastructure. -

APPENDIX I the Economic Benefits and Socioeconomic Effects of The

APPENDIX I The Economic Benefits and Socioeconomic Effects of the Yukon River Road Corridor The Economic Benefits and Socioeconomic Effects of the Yukon River Road Corridor Prepared for the DOWL HKM January 2010 Prepared by In association with Hawley Resource Group Preparers Team Member Project Role Company Patrick Burden Project Manager Northern Economics, Inc. Jonathan King Economist Northern Economics, Inc. Don Schug Socioeconomic Analyst Northern Economics, Inc. Chuck Hawley Minerals Consultant Hawley Resource Group Alexus Bond Staff Analyst Northern Economics, Inc. Eric Davis Staff Intern Northern Economics, Inc. Please cite as: Northern Economics, Inc. The Economic Benefits and Socioeconomic Effects of the Yukon River Road Corridor. Prepared for DOWL HKM. January 2010. Contents Section Page Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. ES-1 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Study Area .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Case Study Communities .................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2 Mineral Deposits and Proposed -

Featured Species-Associated Forest Habitats: Boreal Forest and Coastal Temperate Forest

Appendix 5.1, Page 1 Appendix 5. Key Habitats of Featured Species Appendix 5.1 Forest Habitats Featured Species-Associated Forest Habitats: Boreal Forest and Coastal Temperate Forest There are approximately 120 million acres of forestland (land with > 10% tree cover) in Alaska (Hutchison 1968). That area can be further classified depending on where it occurs in the state. The vast majority of forestland, about 107 million acres, occurs in Interior Alaska and is classified as “boreal forest.” About 13 million acres of forest occurs along Alaska’s southern coast, including the Kodiak Archipelago, Prince William Sound, and the islands and mainland of Southeast Alaska. This is classified as coastal temperate rain forest. The Cook Inlet region is considered to be a transition zone between the Interior boreal forest and the coastal temperate forest. For a map showing Alaska’s land status and forest types, see Figure 5.1 on page 2. Boreal Forest The boreal zone is a broad northern circumpolar belt that spans up to 10° of latitude in North America. The boreal forest of North America stretches from Alaska to the Rocky Mountains and eastward to the Atlantic Ocean and occupies approximately 28 % of the continental land area north of Mexico and more than 60 % of the total area of the forests of Canada and Alaska (Johnson et al. 1995). Across its range, coniferous trees make up the primary component of the boreal forest. Dominant tree species vary regionally depending on local soil conditions and variations in microclimate. Broadleaved trees, such as aspen and poplar, occur in Boreal forest, Nabesna D. -

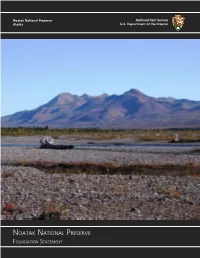

Noatak National Preserve Foundation Statement 2009

Noatak National Preserve National Park Service Alaska U.S. Department of the Interior NOATAK NATIONAL PRESERVE FOUNDATION STATEMENT This page left intentionally blank. Noatak National Preserve Foundation Statement July, 2009 Prepared By: Western Arctic National Parklands National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office National Park Service, Denver Service Center This page left intentionally blank. Table of Contents Noatak National Preserve – Foundation Statement Elements of a Foundation Statement…2 Establishment of Alaska National Parks…3 Summary Purpose Statement…4 Significance Statements…4 Location Regional Map…5 Purpose Statement…6 Significance Statements / Fundamental Resources and Values / Interpretive Themes 1. Arctic-Subarctic River Basin Ecosystem…7 2. Scientific Research...8 3. Subsistence …9 4. Arctic Wilderness…10 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments…11 Workshop Participants…12 Appendix A - Legislation Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act – Selected Excerpts …14 Appendix B – Legislative History Proclamation 4624 – Noatak National Monument, 1978…24 Elements of a Foundation Statement The Foundation Statement is a formal description of Noatak National Preserve’s (preserve) core mission. It is a foundation to support planning and management of the preserve. The foundation is grounded in the preserve’s legislation and from knowledge acquired since the preserve was originally established. It provides a shared understanding of what is most important about the preserve. This Foundation Statement describes the preserve’s