The Mission of the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possible Historical Traces in the Doctrina Addai

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 9.1, 51-127 © 2006 [2009] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press POSSIBLE HISTORICAL TRACES IN THE DOCTRINA ADDAI ILARIA L. E. RAMELLI CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF THE SACRED HEART, MILAN 1 ABSTRACT The Teaching of Addai is a Syriac document convincingly dated by some scholars in the fourth or fifth century AD. I agree with this dating, but I think that there may be some points containing possible historical traces that go back even to the first century AD, such as the letters exchanged by king Abgar and Tiberius. Some elements in them point to the real historical context of the reign of Abgar ‘the Black’ in the first century. The author of the Doctrina might have known the tradition of some historical letters written by Abgar and Tiberius. [1] Recent scholarship often dates the Doctrina Addai, or Teaching of Addai,2 to the fourth century AD or the early fifth, a date already 1 This is a revised version of a paper delivered at the SBL International Meeting, Groningen, July 26 2004, Ancient Near East section: I wish to thank very much all those who discussed it and so helped to improve it, including the referees of the journal. 2 Extant in mss of the fifth-sixth cent. AD: Brit. Mus. 935 Add. 14654 and 936 Add. 14644. Ed. W. Cureton, Ancient Syriac Documents (London 1864; Piscataway: Gorgias, 2004 repr.), 5-23; another ms. of the sixth cent. was edited by G. Phillips, The Doctrine of Addai, the Apostle (London, 1876); G. -

A Tribute to SAC's First Registrar Fr Macarius Wahba

ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁThe Newsletter of SAC Issue 8, December 2020 A Tribute to SAC’s first registrar Fr Macarius Wahba STUDENT REFLECTIONS Congratulations to SAC HIGHLIGHTS OF 2020 Graduates 2020 SAC’s Free Short Online VCE STUDENTS TAKE ON Courses CERT. III IN CHRISTIAN MINISTRY & THEOLOGY ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁ The Newsletter of SAC Issue 8, December 2020 ISSN 2205-2763 (Online) Published by SAC Press 100 Park Rd, Donvale, VIC 3111 Editor: Lisa Agaiby Graphic Design: Bassem Morgan Photo Credits: Bassem Morgan, Shady Nessim, John McDowell, Fr Jacob Joseph, Benjamin Ibrahim, Siby Varghese, Andrea Sherko, Cecily Clark, and Fr Nebojsa Tumara © SAC – A College of the University of Divinity ABN 61 153 482 010 CRICOS Provider 01037A, 03306B www.sac.edu.au/koinonia Feedback: [email protected] ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁ is available in electronic PDF format CONTENTS A Message from the Principal 3 A Tribute to SAC’s First Registrar Fr Macarius Wahba 4 Congratulations to all our SAC Graduates in 2020! 5 Introducing our New Academic Dean: Prof. John Mcdowell 6 Introducing our First Lecturer in Missiology: Fr Dr Jacob Joseph 7 Introducing our Tutor: Shady Nessim 8 Priesthood Ordination of Rev. Fr Jonathan Awad 9 Highlights of 2020 10 VCE Students Take on Cert. III in Christian Ministry & Theology 10 SAC Offers Free Short Online Courses 12 Online Public Lectures 13 International Conferences 14 Manuscript Project at the Monastery of St Paul the Hermit – An Update 15 Student Reflections 16 Reflections on “Coptic Iconography I” by Siby Varghese 16 Reflections on “Coptic Iconography I” by Benjamin Ibrahim 17 Reflections on “Philosophy For Beginners” by Andrea Sherko 18 Reflections on “Atheism” by Andrew E. -

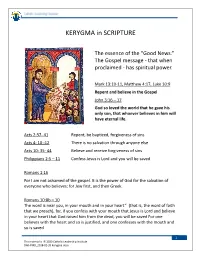

KERYGMA in SCRIPTURE

KERYGMA in SCRIPTURE The essence of the “Good News.” The Gospel message - that when proclaimed - has spiritual power. Mark 13:10-11, Matthew 4:17, Luke 10:9 Repent and believe in the Gospel John 3:16 – 17 God so loved the world that he gave his only son, that whoever believes in him will have eternal life. Acts 2:37- 41 Repent, be baptized, forgiveness of sins Acts 4: 10 -12 There is no salvation through anyone else Acts 10: 35- 44 Believe and receive forgiveness of sins Philippians 2:5 – 11 Confess Jesus is Lord and you will be saved Romans 1:16 For I am not ashamed of the gospel. It is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes: for Jew first, and then Greek. Romans 10:8b – 10 The word is near you, in your mouth and in your heart” (that is, the word of faith that we preach), for, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved For one believes with the heart and so is justified, and one confesses with the mouth and so is saved. 1 This material is © 2020 Catholic Leadership Institute DMI-PMD_2018-02-26 Kerygma.docx In Jesus Christ salvation is offered to all people. He is the Way. Our relationship with God was broken (though not cut off). Through Jesus’ complete outpouring of love the relationship is restored. When we accept by faith that Jesus Christ is Lord, Son of the Father, the one who conquered sin and death by love, we enter His death and resurrection (baptism) leading us to salvation. -

A Comparative Study of Koinonia and the Motivations for Evangelical Ecumenicity

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Western Evangelical Seminary Theses Western Evangelical Seminary 5-1968 A Comparative Study of Koinonia and the Motivations for Evangelical Ecumenicity Howard William Hornby Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/wes_theses Part of the Christianity Commons EVANGELIC.AL ECUMENICITY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the i'iestern Evangelical Seminary In Partial 5Ulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Divinity by Hot-vard hilliam Hornby APPROVED BY Hajar Professor: -·--.lL,_-\:;;;-=trh-!,_;:......;:;__;;._:::..c:...(}_·__..~~~~e::::::::.......==:.....______ _ Cooperative Reader: ~f.lkt.1.L /2;. ~~ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGl~ I. INTRODUCTION . 2 Statement of the Problem • . 2 Justification of the Problem • . 2 Limitations of the Problem •• . 4 Definitions o.f Terms • • . 5 Fellowship • • . 5 Evangelical Ecumenism . 6 Method of Procedure . 6 II. THE .SCRIPTURAL USE OF :fELlDv:SHIP • . 8 Introduction • • • • • • • • • • • . 8 The Old Testament Concept of FellovJship . 9 Fellowship between God and His people . 10 Fellowship between God and individuals • . 14 Fellowship in relation to Israel's hope . 15 The Apocrypha Concept of Fellowship • • • . 16 Passages from the Apocrypha considered • . 17 The New Testament Concept of Fellowship 17 Negative factors of FellOitJship • • . 18 Positive factors of Fellowship • . 19 Expressions of Christian fellovJship . 20 A comprehensive study of the terms • . 22 The scriptural use of koinonas ••• . 22 iii CHAPTER PAGE The scriptural use o:r synl<:oinono s . 25 The scriptural use of koinoneo . 28 The scriptural use of synkoinoneo . • . • . .34 The scriptural use of koinonia )6 Summary • • • • • • • . III. THE HOTIVATIONS I1'0R ECUNENISN ••• . 6o The broad scope of ecumenism . -

The Preface to Luke and the Kerygma in Acts," W

A. J. B. Higgins, “The Preface to Luke and the Kerygma in Acts," W. Ward Gasque & Ralph P. Martin, eds., Apostolic History and the Gospel. Biblical and Historical Essays Presented to F.F. Bruce. Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1970. Hbk. ISBN: 085364098X. pp.78-91. CHAPTER IV The Preface to Luke and the Kerygma in Acts A. J. B. Higgins [p.78] According to ancient tradition Luke both the Gospel and the Acts.1 While the identity of “Luke” is disputed, unity of authorship, including the “we” sections of Acts in their present form, is widely accepted on the basis of style and language.2 The Lukan writings also form a distinct theological unit within the New Testament, so that we can speak of the theology of Luke”.3 The most notable attempt to disprove unity of authorship on linguistic grounds was that of A. C. Clark,4 who tried to demonstrate that the linguistic differences between Luke and Acts are much more important than the resemblances; that they cannot be explained, as Hawkins thought, by the supposition that Acts was written considerably later than the gospel; and that they point, in fact, to different authors. But the complete unsoundness of Clark’s arguments was proved by W. L. Knox.5 The common authorship of the two Lukan writings may be regarded as established. I Does the Lukan preface (Luke 1:1-4) refer only to the gospel, or to both the gospel and Acts?6 The former view is supported by H. Conzelmann7 and E. Haenchen.8 [p.79] In 1953 R. -

The Contribution and Ecumenical Vision of Metropolitan Germanos Strenopoulos and Professor Hamilcar Alivisatos for a “Koinonia of Churches”

Draft outline used during the conference on The Hope of Communion: From 1920 to 2020 The contribution and ecumenical vision of Metropolitan Germanos Strenopoulos and Professor Hamilcar Alivisatos for a “Koinonia of Churches” Prof. Stylianos Tsompanidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I. “Founding Fathers” of the Ecumenical Movement As the famous 1920 Encyclical of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople “Unto the Churches of Christ Everywhere” marks its 100th anniversary, this paper focuses on the contribution and ecumenical vision of Metropolitan Germanos Strenopoulos and Professor Hamilcar Alivisatos for a “Koinonia of Churches”. Both are among those who played a decisive role in the early stages of the Ecumenical Movement and accompanied with brilliant figures, pioneers and enthusiasts of the unitary effort of the Church. They are considered the "founding fathers" of the Ecumenical Movement. Metropolitan Germanos’s role was undeniably fundamental, not only during the drafting of the encyclical, but also during the phase when it was received by the non- Orthodox churches and by the ecumenical movement. The metropolitan, an astute and cultured man, embodied the genuine and mature ecumenical awareness of the Church of Constantinople. Likewise, since 1914 and on, Professor Η. Alivisatos participated in all the meetings and in fact as an active and important member of the ecumenical movements, precursors of the WCC. In 1948, at the founding General Assembly of WCC, Η. Alivisatos and the metropolitan of Thyateira Germanos (Strenopoulos) contributed to the voting of the first Constitution of the WCC.In that way they acted in general terms according to the spirit of the Patriarchal Encyclical and also, they founded the Council on a structure that was not substantially different from the one that was proposed and specified at the time of the circulation of the Encyclical. -

The Eight Sermons of the Kerygma in Acts

The Eight Sermons of the Kerygma in Acts Acts 2:14-36 Then Peter stood up with the Eleven, raised his voice and addressed the crowd: “Fellow Jews and all of you who live in Jerusalem, let me explain this to you; listen carefully to what I say. 15These men are not drunk, as you suppose. It’s only nine in the morning! 16No, this is what was spoken by the prophet Joel: 17“‘In the last days, God says, I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your young men will see visions, your old men will dream dreams. 18Even on my servants, both men and women, I will pour out my Spirit in those days, and they will prophesy. 19I will show wonders in the heaven above and signs on the earth below, blood and fire and billows of smoke. 20The sun will be turned to darkness and the moon to blood before the coming of the great and glorious day of the Lord. 21And everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.’ 22“Men of Israel, listen to this: Jesus of Nazareth was a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs, which God did among you through him, as you yourselves know. 23This man was handed over to you by God’s set purpose and foreknowledge; and you, with the help of wicked men,d put him to death by nailing him to the cross. 24But God raised him from the dead, freeing him from the agony of death, because it was impossible for death to keep its hold on him. -

Kerygmata AO1 Handout

Kerygmata AO1 Handout THE IDEA: The Kerygmata as presented by C.H.Dodd. The principal analysis of the kerygmata of the early Christian community is associated with C.H.Dodd. He reconstructed the main teachings of the early church found in Paul’s letters and then argued that these teachings could be found in the speeches in Acts of the Apostles. He identified six elements common to the speeches that he thought were genuine. QUOTES 1. “The Gospel is not a statement of the general truths of religion, but an interpretation of that which once happened” (Dodd) 2. “To all unprejudiced persons it is manifest that Jesus had not the slightest intention of doing away with the Jewish religion and putting another in its place.” (Reimarus) 3. “The New Testament writers draw a clear distinction between preaching and teaching.” (Dodd) 4. “The kerygma is neither a vehicle for timeless ideas nor the mediator of historical information.” (Bultmann) 5. “Paul himself at least believed that in essentials his Gospel was that of the primitive apostles.” (Dodd) 6. “We have to enquire how far it is possible to discover the actual content of the Gospel preached or proclaimed by the apostles.” (Dodd) EXAMPLES 1. C.H. Dodd wrote about the Kerygma in his book “The Apostolic Preaching and Its Development” (1936) 2. Kerygma signifies not the activity but the content of apostolic preaching. Not the activity, but the message. 3. Dodd (1884- 1973) was born in Denbighshire. 4. Kerygma is a Greek word meaning “proclamation” or “preaching”. 5. Dodd is best known for promoting “realized eschatology”, the belief that Jesus’ references to the kingdom of God meant a present reality rather than a future apocalypse. -

Justin Martyr, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Cyprian of Carthage on Suffering: A

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY JUSTIN MARTYR, IRENAEUS OF LYONS, AND CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE ON SUFFERING: A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL STUDY OF THEIR WORKS THAT CONCERN THE APOLOGETIC USES OF SUFFERING IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THEOLOGY AND APOLOGETICS BY AARON GLENN KILBOURN LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA AUGUST 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Aaron Glenn Kilbourn All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL SHEET JUSTIN MARTYR, IRENAEUS OF LYONS, AND CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE ON SUFFERING: A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL STUDY OF THEIR WORKS THA CONCERN THE APOLOGETIC USES OF SUFFERING IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY Aaron Glenn Kilbourn Read and approved by: Chairperson: _____________________________ Reader: _____________________________ Reader: _____________________________ Date: _____________________________ iii To my wife, Michelle, my children, Aubrey and Zack, as well as the congregation of First Baptist Church of Parker, SD. I thank our God that by His grace, your love, faithfulness, and prayers have all helped sustain each of my efforts for His glory. iv CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………………ix Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….x CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..1 Personal Interest………………………………………………………………………8 The Need for the Study……………………………………………………………….9 Methodological Design……………………………………………………………….10 Limitations……………………………………………………………………………12 CHAPTER 2: THE CONCEPT OF SUFFERING IN THE BIBLE AND EARLY APOLOGISTS........................................................................................................................14 -

The Church As a Eucharistic and Prophetic Community in India: A

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-11-2018 The hC urch as a Eucharistic and Prophetic Community in India: A Theological Exploration into the Challenges and Implications of a Eucharistic Ecclesiology Based on the Early Church and the Statements of the Indian Theological Association (ITA) Shibi Devasia Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Devasia, S. (2018). The hC urch as a Eucharistic and Prophetic Community in India: A Theological Exploration into the Challenges and Implications of a Eucharistic Ecclesiology Based on the Early Church and the Statements of the Indian Theological Association (ITA) (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1433 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHURCH AS A EUCHARISTIC AND PROPHETIC COMMUNITY IN INDIA: A THEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION INTO THE CHALLENGES AND IMPLICATIONS OF A EUCHARISTIC ECCLESIOLOGY BASED ON THE EARLY CHURCH AND THE STATEMENTS OF THE INDIAN THEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (ITA) A Dissertation Submitted to McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology By Shibi Devasia May 2018 Copyright by Shibi Devasia 2018 ABSTRACT THE CHURCH AS A EUCHARISTIC AND PROPHETIC COMMUNITY IN INDIA: A THEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION INTO THE CHALLENGES AND IMPLICATIONS OF A EUCHARISTIC ECCLESIOLOGY BASED ON THE EARLY CHURCH AND THE STATEMENTS OF THE INDIAN THEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (ITA) By Shibi Devasia May 2018 Dissertation supervised by Dr. -

Jn1:14) Editorial Our Lord

Volume 4, Issue 12 Christmas 2010 And the Word was Made Flesh... (Jn1:14) Editorial our Lord. As a newcomer, coming to know the history of the Church in the Continuum, I’ve come to terms with certain realities: Mistakes and misguided leadership has left its mark, but nevertheless, the Congress of St. Louis was an excellent beginning as seen in the presidential ad- dress of Perry Laukhuff and the Affirmation of St. Louis (published again for your reading). Wonder what happened to that fire for the Lord? Even after three decades of the legacy of the Congress of St. Louis we are found wanting in serving the Great Commission – more groups have emerged, more splits, more cafeteria Anglicanism com- promising the essentials of faith and practice. The Oxford movement was a lay movement to begin with, when laymen called attention of the Anglicans to their Catholic roots- magine you are rector of the church and the door bell continu- Catholic, in as much our faith and orders, an inheritance from the ously rings. On the other side of the door stand parents, desiring I Apostles, steeped in the two millennia of Christendom. baptism for their children. That’s what Fr. Kern experiences nearly every Within the Holy Catholic Church Anglican Rite, there have day. December 21, 2010 marked his 50th anniversary as a priest. This been efforts to remove laity and clergy from decision making process year alone Fr. Kern has administered the sacrament of baptism more by the adoption of the Apostolic Canons that deny them seat, voice than two hundred times. -

The New Testament Student Outline

The nstitute for atechesis and ormation Course Outline for Students ICF 103 – The New Testament God’s covenant of love with the human person is fulfilled in the life, death and resurrection of His only Son, Jesus Christ. This course picks up the “Story of Salvation” in its fulfillment in the coming of Christ and the establishment of His Church. It will begin with an introduction to the Gospels, Apostolic preaching and the origins of the Church, and conclude with the conversion, preaching and travels of St. Paul. Texts: The Bible: http://www.usccb.org/bible/books-of-the-bible/ The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC): http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc.htm Supplemental Reading/Additional Resources: St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology: http://www.salvationhistory.com/ 1 | P a g e Student Outline ICF 104 – New Testament Revised: 5/2017 Week 1: Origins of Scripture and the New Testament Weekly Reading Before Class: CCC 101 -130; Mark 1-3;4:26-32; 8:22-38; 9:1-8, 30-32; 10:13-16, 32-34 What is the Bible? The word of God God’s revelation of Himself to us God makes Himself known to us through a gradual process God reveals Himself in order to enter into a relationship with us Biblical Authorship Divine inspiration Human authorship The Canon of Scripture Canon (Greek) – “rule” The Church is the authority on the Canon of Scripture (which books are authentically works of God’s Revelation). Biblical Interpretation (CCC 115-118) The Church employs certain principles when interpreting Sacred Scripture, taking into account: The sacred author’s intention The content and unity of the whole of Scripture Reading Scripture within the living Tradition of the whole Church Being attentive to the analogy of faith The New Testament I.