Humanity and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captivating Technology

Ruha Benjamin editoR Captivating teChnology RaCe, CaRCeRal teChnosCienCe, and libeRatoRy imagination ine ev Ryday life captivating technology Captivating Technology race, carceral technoscience, and liberatory imagination in everyday life Ruha Benjamin, editor Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Kim Bryant Typeset in Merope and Scala Sans by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Benjamin, Ruha, editor. Title: Captivating technology : race, carceral technoscience, and liberatory imagination in everyday life / Ruha Benjamin, editor. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018042310 (print) | lccn 2018056888 (ebook) isbn 9781478004493 (ebook) isbn 9781478003236 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478003816 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Prisons— United States. | Electronic surveillance— Social aspects— United States. | Racial profiling in law enforcement— United States. | Discrimination in criminal justice administration— United States. | African Americans— Social conditions—21st century. | United States— Race relations—21st century. | Privacy, Right of— United States. Classification: lcc hv9471 (ebook) | lcc hv9471 .c2825 2019 (print) | ddc 364.028/4— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018042310 An earlier version of chapter 1, “Naturalizing Coersion,” by Britt Rusert, was published as “ ‘A Study of Nature’: The Tuskegee Experiments and the New South Plantation,” in Journal of Medical Humanities 30, no. 3 (summer 2009): 155–71. The author thanks Springer Nature for permission to publish an updated essay. Chapter 13, “Scratch a Theory, You Find a Biography,” the interview of Troy Duster by Alondra Nelson, originally appeared in the journal Public Culture 24, no. -

Informed Refusal: Reprints and Permission: Sagepub.Com/Journalspermissions.Nav DOI: 10.1177/0162243916656059 Toward a Justice- Sthv.Sagepub.Com Based Bioethics

Article Science, Technology, & Human Values 1-24 ª The Author(s) 2016 Informed Refusal: Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0162243916656059 Toward a Justice- sthv.sagepub.com based Bioethics Ruha Benjamin1 Abstract ‘‘Informed consent’’ implicitly links the transmission of information to the granting of permission on the part of patients, tissue donors, and research subjects. But what of the corollary, informed refusal? Drawing together insights from three moments of refusal, this article explores the rights and obligations of biological citizenship from the vantage point of biodefectors— those who attempt to resist technoscientific conscription. Taken together, the cases expose the limits of individual autonomy as one of the bedrocks of bioethics and suggest the need for a justice-oriented approach to science, medicine, and technology that reclaims the epistemological and political value of refusal. Keywords ethics, justice, inequality, protest, politics, power, governance, other, engagement, intervention 1Department of African American Studies, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Corresponding Author: Ruha Benjamin, Department of African American Studies, Princeton University, 003 Stanhope Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2016 2 Science, Technology, & Human Values In this article, I investigate the contours of biological citizenship from the vantage point of the biodefector—a way of conceptualizing those who resist -

South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet

South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet Architecture of the Internet COOKIES: A piece of data stored on a person’s computer by a website to enable the site to “remember” useful information, such as previous browsing history on the site or sign-in information. • Website cookies explained | Guardian Animations - YouTube ALGORITHMS: A set of instructions to be followed, usually applied in computer code, to carry out a task. Algorithms drive content amplification, whether that’s the next video on YouTube, ad on Facebook, or product on Amazon. Also, the algorithms serve a very specific economic purpose: to keep you using the app or website in order to serve more ads. • Review Facebook’s Ad Policy • Visit Your Ad Choices and run a diagnostic test on your computer or phone FILTER BUBBLES: Intellectual isolation that results from information served primarily through search engines that filter results based on personalized data, creating a “bubble” that isolates the user from information that may not align with their existing viewpoints. • Have Scientists Found a Way to Pop the Filter Bubble? | Innovation | Smithsonian Magazine What can you do to protect yourself? • Visit Electronic Frontier Foundation for tools to protect your online privacy. • Visit FTC.gov for more information on cookies and understanding online tracking Additional Resources • Is your device listening to you? 'Your Social Media Apps are Not Listening to You': Tech Worker Explains Data Privacy in Viral Twitter Thread (newsweek.com) • “Website Cookies Explained | The Guardian Animations” South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet • “How Recommendation Algorithms Run The World,” Wired. -

UNI Quest for Racial Equity Project

Race to the Future? Reimagining the Default Settings of Technology & Society University of Northern Iowa - Quest for Racial Equity Project Dr. Ruha Benjamin, Princeton University Professor of African American Studies, primarily researches, writes, and speaks on the intersection of technology with health, equity, and justice. She is the author of: Race After technology: Abolitionist Tools for the Next Jim Code and People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem cell Frontier. In this 35-minute presentation, Dr. Benjamin discusses and provides examples of how the design and implementation of technology has intended and unintended consequences which support systematic racism. She asks the audience to imag- ine a world in which socially conscious approaches to technology development can intentionally build a more just world. Your Tasks: • Watch Race to the Future? Reimagining the default settings of technology and society, Dr. Ruha Benjamin’s presentation from the 2020 NCWIT Conversations for Change Series. (https://www.ncwit.org/video/race-future-reimagining-default-settings-technology-and-society-ruha-benjamin-video-playback) • Together with 1 or 2 other Quest participants, have a discussion using one or more of the question groups below. If you are questing on your own, choose 2-3 questions and journal about each question you choose for 7 minutes. • Finally, make a future technology pledge. Your pledge could be about questioning new technologies, changing your organization's policies about technology adoption, or something else. Questions -

People's Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier

SREXXX10.1177/2332649215581326Sociology of Race and EthnicityBook Reviews 581326research-article2015 Book Reviews Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2015, Vol. 1(3) 461 –465 People’s Science: Bodies © American Sociological Association 2015 sre.sagepub.com and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier Ruha Benjamin People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0804782975, 272 pp. Reviewed by: Jonathan Kahn, Hamline University School of Law, St Paul, MN, USA DOI: 10.1177/2332649215581326 In this post-9/11 world, few people remember that the People’s Science eschews engagement with the defining act of George W. Bush’s early presidency fraught prolife politics that gave rise to President was his announcement on August 9, 2001, restricting Bush’s initial announcement to focus on how the the use of federal funds for research on human embry- California campaign raised a different set of ques- onic stem cells. In the following months some scien- tions implicating diverse actors who variously tists declared that they would take their labs overseas made claims upon the institutional structures man- to work in jurisdictions more congenial to stem cell dated by Proposition 71 or who had claims made research; others called for nonfederal sources to step upon them as part of the process of enlisting sup- into the breach. A number of states heeded the call, port both for the proposition and for subsequent foremost among them California, which introduced research endeavors. Proposition 71 to the electorate to authorize the issu- The book begins by introducing the campaign ance of $3 billion in state bonds over 10 years to fund and its key actors and then moves on to a series of stem cell research. -

Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, Cambridge: Polity, 2019

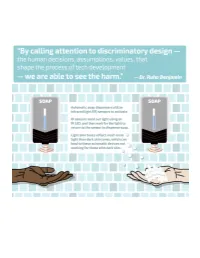

Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, Cambridge: Polity, 2019. ISBN: 978-1-509-52639-0 (cloth); ISBN: 978-1-509-52640-6 (paper); ISBN: 978-1-509-52643-7 (ebook) Ruha Benjamin’s new book, Race After Technology, is powerful and engaging survey of the racialization of emerging digital technologies. Foundationally, her argument is relatively straightforward, that new technologies are not socially neutral, but rather are embedded within and actively entrench existing structures of white supremacy. Complex algorithms and quotidian apps veil these social effects, naturalizing discrimination as simply descriptive statistics. This constitutes what Benjamin calls the New Jim Code: “new technologies that reflect and reproduce existing inequities but that are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era” (p.5-6). Critiquing the relationship between emerging digital technologies and race, Benjamin outlines a new interdisciplinary subfield that she terms “race critical code studies”. In the Introduction, she characterizes race critical code studies as “defined not just by what we study but also by how we analyze, questioning our own assumptions about what is deemed high theory versus pop culture, academic versus activist, evidence versus anecdote” (p.45). Where data infrastructures imperialistically present an increasingly total vision, extracting data from all aspects of life, Benjamin pushes against these totalizing narratives and calls instead for “thin description”, elastically stretching to engage “fields of thought and action too often disconnected” (p.45). Her analysis pivots from social theory and scholarly studies to tweets and anecdotes, which she describes “as a method for reading surfaces – such as screens and skin” (ibid.). -

Race Critical Code Studies

This is a repository copy of Now to imagine a different world? Race critical code studies. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/165352/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Williams, R. orcid.org/0000-0002-4295-2582 (2020) Now to imagine a different world? Race critical code studies. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6 (4). pp. 569-571. ISSN 2332- 6492 https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220942518 Williams R. Now to Imagine a Different World? Race Critical Code Studies. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 2020;6(4):569-571. Copyright © 2020 American Sociological Association. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220942518. Article available under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Now to imagine a different world? Race critical code studies Racing Science and Technology Studies Building on the insights both of critical race theory and STS, Ruha Benjamin synthesises a broad-ranging set of examples to elaborate race critical code studies. -

ACAB Even Facebook Admins’: Platform Vernaculars, Community Moderation and Surveillance in Facebook Groups

‘ACAB even Facebook admins’: Platform Vernaculars, Community Moderation and Surveillance in Facebook Groups ‘ACAB even Facebook admins’: Platform Vernaculars, Community Moderation and Surveillance in Facebook Groups Sab D’Souza March 2021 The Women of Colour (WOC) Web was an autonomous Facebook group for women and non-binary people of colour. It offered a safe alternative to other, typically white, feminist spaces on and offline. What started as a single group grew into an ecosystem of subgroups that sprouted from the diverging aspects of its members’ identities. At its peak, The WOC Web had over 3000 members from across ‘Australia’, which fluctuated throughout its five-year operation. I joined in 2013 and was exposed to a language that described what I had always known viscerally. I opened up to others who, in turn, opened themselves up to me – this intimacy rewarded us with a profound pleasure in each other’s digital proximity. Sara Ahmed (2014) describes queer pleasure as a specific feeling that erupts when one refuses to comply with the dominant scripts of heterosexuality. In a sense, our pleasure was produced through our refusal to comply with the dominant scripts of whiteness. If I passed a member on the street, at a protest, at the pub, or across campus, we would steal a glance and smile. However, in 2017, following a string of privacy breaches and mounting tensions between admins and users, the network was abruptly deleted. In 2019, I sat with six former members of The WOC Web to reflect on the group and its deletion. In this essay, I describe the group as predicated on a culture of risk and safety management, an online space which employed the logics and practices of policing to an already marginalised user base. -

Mellon Serving Institutions

Through the program in Higher Education and Scholarship in the Humanities, the Foundation assists colleges, universities, and research institutes. Among these institutions are research universities, liberal arts colleges, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Tribal Colleges and Universities, and Hispanic- Mellon Serving Institutions. In practical terms, this means helping institutions train scholars and produce scholarship in the humanities broadly conceived; fostering practices of diversity and inclusion and promoting the social value Summer 2021 of the humanities; responding to the economic, demographic, financial, and technological challenges affecting higher education; and expanding access and support degree completion. Research Institute Lincoln University President Brenda A. Allen submitted a proposal to The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which resulted in a $500,000 grant to invest in Lincoln University’s teaching pedagogy and humanities programs. “This generous gift from the Mellon Foundation represents a major step toward garnering the resources we need to achieve our educational goals and reinvest in our roots as a liberal arts institution,” said Allen. “With this grant, we will work with faculty on incorporating active learning pedagogies and enhancing curricular and co-curricular opportunities for our students.” Special thanks to . Sharone Jones Assistant Vice President, Student Success & Experiential Learning Michael Lynch Director, Center for Undergraduate Research Crystal Faison Director, Office of Internship Services -

Ruha Benjamin's Race After Technology

I', ,·I,I, ; I !!liilfl 111111 11 1 11 1, ytirne I went back to di 1l1t1 (1 ll'M:1tio 11 of trying to keep the tlhi 1, 111111d n,1d light from the helicopter 111d11w\ thin pane. Like everyone who 1 l1 c1 11'ih p1d1 c<.! d neighborhood, I grew up with Introduction 11 11c 11 1,o ol htii11 g watched. Family, friends, and 11 1glii 1i ii '~ n II of us caught up in a carceral web, in The New Jim Code v Iii, 11 , ti 11< •1· p<.:o ple's safety and freedom are predicated I Ill I II II l Oil t:li nment. Now, in the age of big data, many of us continue f n ht.: monitored and measured, but without the audi ble rumble of helicopters to which we can point. This doesn't mean we no longer feel what it's like to be a Naming a child is serious business. And if you are not problem. We do. This book is my attempt to shine light White in the United States, there is much more to it than in the other direction, to decode this subtle but no less personal preference. When my younger son was born hostile form of systemic bias, the New Jim Code. I wanted to give him ari Arabic name to reflect part of our family heritage. But it was not long after 9/11, so of course I hesitated. I already knew he would be profiled as a Black youth and adult, so, like most Black moth ers, I had already started mentally sparring those who would try to harm my child, even before he was born. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Racial Distinctions in Middle-Class Motherhood: Ideologies and Practices of African-American Middle-Class Mothers Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4t10c8zf Author Dow, Dawn Marie Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Racial Distinctions in Middle-Class Motherhood: Ideologies and Practices of African-American Middle-Class Mothers By Dawn Marie Dow A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Raka Ray, Chair Professor Barrie Thorne Professor Evelyn Nakano Glenn Fall 2012 Abstract Racial Distinctions in Middle-Class Motherhood: Ideologies and Practices of African-American Middle-Class Mothers by Dawn Marie Dow Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Raka Ray, Chair My dissertation examines how intersections of racial identity, class and gender influence the cultural expectations and decisions of African-American middle-class mothers regarding work, family and parenting. Through this research I challenge three dominant sets of ideologies present in family, work and parenting scholarship. First, I challenge the widespread acceptance of the Intensive Mothering ideology that views mothers as principally responsible for raising their children within a nuclear family context. Second, I challenge the conflict paradigm that assumes a mother’s decisions about work and family can be captured in a competing spheres framework. This framework assumes that mothers who allot more time to work have a stronger “work devotion” and those who allot more time to family have a stronger “family devotion.” Third, I challenge the assumption that middle-class parents are primarily influenced by their class status when parenting their children and primarily use the concerted cultivation parenting approach. -

Advancing Racial Literacy in Tech Featuring Dr

Advancing Racial Literacy in Tech Featuring Dr. Howard Stevenson February 4, 2020 Thank you for coming to this conversation. I'm really excited. My name's is Mutale. I am a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center, and this conversation that I'm hosting is part of my ongoing work. But I'm most excited to host it during Black History Month-- and wearing my black, red, and green for unity and liberation, just to let you know. So welcome. So this conversation is being recorded. We are not alone, so please be mindful of what you say, in terms of comments. If you do want to tweet at us, our handle is @BKCHarvard. And I am very excited, so just a little bit of place setting-- I have worked in technology for the last seven years, but 10 years prior to that, I was actually a journalist. I worked in broadcast at the BBC, and the beat that I looked at was science, technology, and youth-- which ultimately meant black people-- what are the black people doing, and how can you help us tell those stories? I moved to the US around 14 years ago now, worked at CNN, and ABC, and all the letters. If that's your field, come and find me [INAUDIBLE] same newsroom, different boss, basically. And I got roped into technology around 2013 in New York City, when we were first starting to have hackathons and first thinking about teaching kids to code. And that work led me into non-profits, led me to Google, led me to ultimately Weapons of Math Destruction, which is a book by Cathy O'Neill.