Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arkansas Department of Health 1913 – 2013

Old State House, original site of the Arkansas Department of Health 100 years of service Arkansas Department of Health 1913 – 2013 100yearsCover4.indd 1 1/11/2013 8:15:48 AM 100 YEARS OF SERVICE Current Arkansas Department of Health Location Booklet Writing/Editing Team: Ed Barham, Katheryn Hargis, Jan Horton, Maria Jones, Vicky Jones, Kerry Krell, Ann Russell, Dianne Woodruff, and Amanda Worrell The team of Department writers who compiled 100 Years of Service wishes to thank the many past and present employees who generously provided information, materials, and insight. Cover Photo: Reprinted with permission from the Old State House Museum. The Old State House was the original site of the permanent Arkansas State Board of Health in 1913. Arkansas Department of Health i 100 YEARS OF SERVICE Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR ................................................................................................. 1 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 4 INFECTIOUS DISEASE .......................................................................................................................... 4 IMMUNIZATIONS ................................................................................................................................. 8 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH -

Harry S. Ashmore Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4c60383f No online items Preliminary Guide to the Harry S. Ashmore Collection Preliminary arrangement and description by Special Collection staff; latest revision D. Tambo Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Preliminary Guide to the Harry S. Mss 155 1 Ashmore Collection Preliminary Guide to the Harry S. Ashmore Collection, ca. 1922-1997 [bulk dates 1950s-1980s] Collection number: Mss 155 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Processed by: Preliminary arrangement and description by Special Collection staff; latest revision D. Tambo Date Completed: Aug. 23, 2007 Encoded by: A. Demeter © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Harry S. Ashmore Collection Dates: ca. 1922-1997 Bulk Dates: 1950s-1980s Collection number: Mss 155 Creator: Ashmore, Harry S. Collection Size: 20 linear feet (15 record containers, 2 document boxes, and 19 audiotapes). Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Abstract: Addresses and speeches, awards, biographical information, correspondence, writings, photographs, audiotapes and videotapes of the newspaperman, writer, editor-in-chief of Encyclopaedia Britannica, and executive for the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Awarded the first double Pulitzer Prizes in history for distinguished service in the Little Rock school integration controversy of the 1950s. -

The Ku Klux Klan in American Politics

L I B RARY OF THE UN IVERSITY OF ILLINOIS "R3GK. cop. 2. r ILLINOIS HISTORY SURVEY LIBRARY The Ku Klux Klan In American Politics By ARNOLD S. RICE INTRODUCTION BY HARRY GOLDEN Public Affairs Press, Washington, D. C. TO ROSE AND DAVE, JESSIE AND NAT -AND, OF COURSE, TO MARCIA Copyright, 1962, by Public Affairs Press 419 New Jersey Avenue, S. E., Washington 3, D.C. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 61-8449 Ste3 >. V INTRODUCTION There is something quite frightening about this book. It is not so much that Dr. Rice recounts some of the brutalities and excesses of the Ku Klux Klan or even that he measures the intelligence of those who led the cross-burners as wanting; indeed, those of us who lived through the "kleagling" of the 1920's remember that the Klansmen, while not men, weren't boys either. What is frightening is the amount of practical action the successors to the Klan have learned from it. They have learned not only from the Klan's mistakes but from the Klan's successes. Fortunately, neither the John Birch Society nor the White Citizens Councils nor the revivified Klan nor the McCarthyites have learned well enough to grasp ultimate power. All of them, however, have learned enough so that they are more than an annoyance to the democratic process. Just how successful was the Klan? It never played a crucial role in a national election. The presence of Klansmen on the floor of a national political convention often succeeded in watering down the anti-Klan plank but national candidates, if they chose, could casti- gate the Klan at will. -

The David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History

The David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History University of Arkansas 365 N. McIlroy Ave. Fayetteville, AR 72701 (479) 575-6829 Arkansas Memories Project - Event Dale Bumpers and David Pryor Pope County Democratic Party Banquet October 8, 2009 Arkansas Tech University Russellville, Arkansas Event Description On October 8, 2009, Olin Cook, a representative to the state Democratic Committee and past chair of the Pope County Democrats introduced Senators Dale Bumpers and David Pryor as the guests of honor at a Democratic Party banquet at Arkansas Tech University in Russellville. Both Pryor and Bumpers shared stories about their political careers with the attendees. Dubbed "the Arkansas version of The Antique Roadshow" by Senator Pryor, they entertained the audience with anecdotes about Orval Faubus, J.W. Fulbright, Robert Byrd, Bill Clinton, and others. Copyright 2010 Board of Trustees of the University of Arkansas. All rights reserved. Transcript: [00:00:00] [Introductory music] [Conversations in audience] [Applause] [00:00:23] Jim Kennedy: Now I’ve got a—a special thing. I’d like a lady to come up here and just tell a quick little story, and we’re going to get on with our program. This is a historic event, and I’m sure thankful y’all are here. This is Lynn Wiman. Miss Wiman, I’ll let you have the podium. Lynn Wiman: I’m Lynn Wiman, and I have Vintage Books on Parkway, and I am very much the most unlikely participant in a political banquet, so excuse me, I’m very nervous. But I wanted to tell you something about Senator Pryor. -

Cubs Daily Clips

March 31, 2017 Cubs.com, Russell, Rizzo homer; Anderson solid for 5 http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/221635936/astros-cubs-combine-for-4-hrs-in-exhibition/ Cubs.com, Lester earns right to start Opening Night http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/221580806/jon-lester-to-face-cardinals-on-opening-night/ Cubs.com, Cubs remain top dog in NL Central http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/221652876/chicago-cubs-remain-team-to-beat-in-nl-central/ Cubs.com, La Stella relieved to learn he's on roster http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/221623856/tommy-la-stella-on-making-cubs-roster/ Cubs.com, Maddon: Cubs turning page, aiming to repeat http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/221628170/joe-maddon-gets-cubs-ready-for-regular-season/ ESPNChicago.com, Curse-breaking Chicago Cubs not afraid to change http://www.espn.com/blog/chicago/cubs/post/_/id/43516/curse-breaking-cubs-not-afraid-to-change CSNChicago.com, Follow The Leader: What Makes Theo Epstein An Unstoppable Force For Cubs http://www.csnchicago.com/chicago-cubs/follow-leader-what-makes-theo-epstein-unstoppable-force-cubs CSNChicago.com, How Justin Grimm Could Be X-Factor In Cubs Bullpen http://www.csnchicago.com/chicago-cubs/how-justin-grimm-could-be-x-factor-cubs-bullpen Chicago Tribune, World Series goal achieved, Theo Epstein sets sights on Cubs empire http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-theo-epstein-cubs-empire-spt-0402-20170331- story.html Chicago Tribune, What if Cubs had lost Game 7? Line between agony, afterglow so thin http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-cubs-world-series-almost-goats-spt-0331-20170330- -

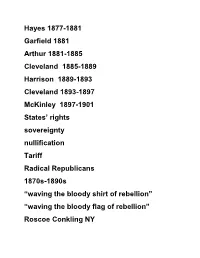

List for 202 First Exam

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

Gazette Project Interview with Roy Reed Little Rock

Gazette Project Interview with Roy Reed Little Rock, Arkansas, 15 March 2000 Interviewer: Harri Baker Harri Baker: This is a continuation of interviews with Roy Reed and Harri Baker. This is March 15th in the year 2000. Roy, we had carried your story right up to the point where you are about to get hired by the Arkansas Gazette. So, how did that come about? It is the year of 1956. I understand that a childhood friend of yours was a printer at the Gazette and was somehow involved in the process. Roy Reed: That’s right. His name was Stan Slaten. Stanley and I grew up together in Piney, on the outskirts of Hot Springs. We chased girls together. In fact - -- I can’t remember if I told this or not --- Stanley wrecked my Model A pickup truck because he couldn’t stand it that the girl sitting between us was paying more attention to me than to him. He took his hands off the wheel just long enough to run off the bluff. Nobody was hurt. Stanley and I used to go out on the river, the Ouachita River, and put out trot lines. Now and then, we would get a hold of --- It seems to me the most whiskey that we were able to buy, between the two of us, was probably a pint or a half of a pint. With boys that are fifteen years old, that is about all it takes. We would build a fire and heat up wieners and do the things that 1 boys do that they consider necessary in growing up. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V. -

Dafydd Jones: the Last Hurrah Dafydd Jones: the Last Hurrah 3 Aug–8 Sep 2018

PRINT SALES GALLERY 3 AUG–8 SEP 2018 DAFYDD JONES: THE LAST HURRAH DAFYDD JONES: THE LAST HURRAH 3 AUG–8 SEP 2018 Snoggers, Hammersmtih Palais, London, 1981 British photographer Dafydd Jones (b.1956) has worked as social photographer since the early 1980s, contracted by such publications as Tatler, Vanity Fair, The New York Observer, The Sunday Telegraph, The Times and Independent. After winning a prize in a photography competition run by The Sunday Times magazine in 1981 with a set of pictures of the ‘Bright Young Things’, Jones was hired by Tatler magazine editor Tina Brown to photograph Hunt Balls, society weddings and debutante dances. This exhibition explores Jones’s behind-the-scenes images taken in the years that followed, between 1981-1989, known as ‘The Tatler Years’. “I had access to what felt like a secret world. It was a subject that had been written about and dramatised but I don’t think any photographers had ever tackled before. There was a change going on. Someone described it as a ‘last hurrah’ of the upper classes.” SELECTED PRESS THE GUARDIAN, 8 AUG 2018 I took this shot at Oriel College, Oxford, in 1984. I had heard that whoever won the summer rowing competition would set fire to a boat in celebration. Oriel had won seven years in a row at that point, and I remember there were complaints that it was all getting out of hand. The whole event was slightly mad. After a long, boozy dinner, groups of suited men would run arm-in-arm and jump through the blaze, or dash through the embers in their smart shoes. -

The Progressive Pittsburgh 250 Report

Three Rivers Community Foundation Special Pittsburgh 250 Edition - A T I SSUE Winter Change, not 2008/2009 Social, Racial, and Economic Justice in Southwestern Pennsylvania charity ™ TRCF Mission WELCOME TO Three Rivers Community Foundation promotes Change, PROGRESSIVE PITTSBURGH 250! not charity, by funding and encouraging activism among community-based organiza- By Anne E. Lynch, Manager, Administrative Operations, TRCF tions in underserved areas of Southwestern Pennsylvania. “You must be the change you We support groups challeng- wish to see in the world.” ing attitudes, policies, or insti- -- Mohandas Gandhi tutions as they work to pro- mote social, economic, and At Three Rivers Community racial justice. Foundation, we see the world changing every day through TRCF Board Members the work of our grantees. The individuals who make up our Leslie Bachurski grantees have dedicated their Kathleen Blee lives to progressive social Lisa Bruderly change. But social change in Richard Citrin the Pittsburgh region certainly Brian D. Cobaugh, President didn’t start with TRCF’s Claudia Davidson The beautiful city of Pittsburgh (courtesy of Anne E. Lynch) Marcie Eberhart, Vice President founding in 1989. Gerald Ferguson disasters, and nooses show- justice, gay rights, environ- In commemoration of Pitts- Chaz Kellem ing up in workplaces as re- mental justice, or animal Jeff Parker burgh’s 250th birthday, I was cently as 2007. It is vital to rights – and we must work Laurel Person Mecca charged by TRCF to research recall those dark times, how- together to bring about lasting Joyce Redmerski, Treasurer the history of Pittsburgh. Not ever, lest we repeat them. change. By doing this, I am Tara Simmons the history that everyone else Craig Stevens sure that we will someday see would be recalling during this John Wilds, Secretary I’ve often heard people say true equality for all. -

Group Tour Manual

Group Tour GUIDE 1 5 17 33 36 what's inside 1 WELCOME 13 FUN FACTS – (ESCORT NOTES) 2 WEATHER INFORMATION 17 ATTRACTIONS 3 GROUP TOUR SERVICES 30 SIGHTSEEING 5 TRANSPORTATION INFORMATION 32 TECHNICAL TOURS Airport 35 PARADES Motorcoach Parking – Policies 36 ANNUAL EVENTS Car Rental Metro & Trolley 37 SAMPLE ITINERARIES 7 MAPS Central Corridor Metro Forest Park Downtown welcome St. Louis is a place where history and imagination collide, and the result is a Midwestern destination like no other. In addition to a revitalized downtown, a vibrant, new hospitality district continues to grow in downtown St. Louis. More than $5 billion worth of development has been invested in the region, and more exciting projects are currently underway. The Gateway to the West offers exceptional music, arts and cultural options, as well as such renowned – and free – attractions as the Saint Louis Art Museum, Zoo, Science Center, Missouri History Museum, Citygarden, Grant’s Farm, Laumeier Sculpture Park, and the Anheuser-Busch brewery tours. Plus, St. Louis is easy to get to and even easier to get around in. St. Louis is within approximately 500 miles of one-third of the U.S. population. Each and every new year brings exciting additions to the St. Louis scene – improved attractions, expanded attractions, and new attractions. Must See Attractions There’s so much to see and do in St. Louis, here are a few options to get you started: • Ride to the top of the Gateway Arch, towering 630-feet over the Mississippi River. • Visit an artistic oasis in the heart of downtown. -

Historic Resource Study

Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument _____________________________________________________ Prepared for the National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington Minidoka Internment National Monument Historic Resource Study Amy Lowe Meger History Department Colorado State University National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………… i Note on Terminology………………………………………….…………………..…. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………. iii Part One - Before World War II Chapter One - Introduction - Minidoka Internment National Monument …………... 1 Chapter Two - Life on the Margins - History of Early Idaho………………………… 5 Chapter Three - Gardening in a Desert - Settlement and Development……………… 21 Chapter Four - Legalized Discrimination - Nikkei Before World War II……………. 37 Part Two - World War II Chapter Five- Outcry for Relocation - World War II in America ………….…..…… 65 Chapter Six - A Dust Covered Pseudo City - Camp Construction……………………. 87 Chapter Seven - Camp Minidoka - Evacuation, Relocation, and Incarceration ………105 Part Three - After World War II Chapter Eight - Farm in a Day- Settlement and Development Resume……………… 153 Chapter Nine - Conclusion- Commemoration and Memory………………………….. 163 Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 173 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………. 181 Cover: Nikkei working on canal drop at Minidoka, date and photographer unknown, circa 1943. (Minidoka Manuscript Collection, Hagerman Fossil