Review Rohingya Influx Since 1978 Thematic Report – December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

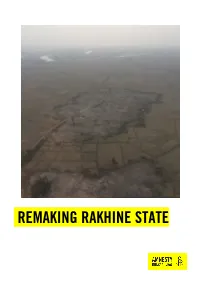

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

1 by Shahinur Bashar the Rohingya Refugee

The Rohingya Refugee Crisis in Bangladesh: Environmental Impacts, Policies, and Practices By Shahinur Bashar MPP Essay Submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Public Policy 1 Presented on July 12, 2021 Master of Public Policy Essay of Shahinur Bashar APPROVED: Erika Allen Wolters, Committee Chair David Bernell, Committee Member Brent S. Steel, Committee Member Shahinur Bashar, Author 2 Abstract The Rohingya community have faced continuous violence, discrimination and statelessness in the Rakhine State of Myanmar. In 2017, a violent crackdown by Myanmar’s army on Rohingya Muslims sent almost a million fleeing across the border of Bangladesh. They found their temporary home in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh – now the largest refugee camp in the world. As a result of the sudden influx to Cox’s Bazar, a hotspot of enriched bio-diversity, the area is facing severe challenges to maintain the natural ecosystem. Regions like Teknaf, with a wildlife sanctuary of about 11,615 ha are now almost deserted. This paper aims to describe the major environmental effects of the Rohingya refugee influx including: deforestation, severe water scarcity and pollution, wildlife habitat loss, fragmentation, and destruction, poor management of solid and human waste, improper drainage systems, air pollution, surface water pollution, etc. Moreover, the paper seeks to analyze the policies, practices and role of the host-community government to mitigate the effects. While there are notable successful projects, like the Refugee, Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC) providing liquefied petroleum gas (LPGs) to meet energy needs of the Rohingya, impacts to biodiversity continues to be affected by lack of usable water and wildlife destruction. -

Download File

UNICEF ADVOCACY ALERT | August 2019 UNICEF ADVOCACY ALERT | August 2019 BEYOND SURVIVAL SURVIVAL ROHINGYA REFUGEE ROHINGYACHILDREN REFUGEE IN BANGLADESH CHILDREN IN BANGLADESH WANT TO LEARN WANT TO LEARN UNICEF Bangladesh thanks its partners and donors without whom its work on behalf of Rohingya children would not be possible Cover photo: Children at a UNICEF-supported Learning Centre in Kutupalong refugee camp © UNICEF/Brown Published by UNICEF Bangladesh BSL Offi ce Complex, 1 Minto Road, Dhaka – 1000, Bangladesh © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 #AChildisAChild BEYOND SURVIVAL ROHINGYA REFUGEE CHILDREN IN BANGLADESH WANT TO LEARN Refugee Population in Cox’s Bazar District April 2019 | Sources: ISCG, RRRC, UNHCR, IOM-NPM, Site Management Sector | Projection: BUTM CONTENTS 4 BEYOND SURVIVAL 6 Frustration in a fragile setting 8 DESPERATE TO LEARN 10 First steps towards quality learning 12 Big issues remain 14 Adolescents risk missing out 18 A CLARION CALL FOR EDUCATION 20 MEETING THE NEEDS OF ROHINGYA REFUGEE CHILDREN 22 Building bridges between the communities 24 Darkness exposes women and girls to danger 27 At the mercy of traffi ckers 30 Vigilance against the threat of cholera 32 Youngest children remain at risk 34 Piped networks give more families access to safe water 38 CALL TO ACTION 42 UNICEF BANGLADESH ROHINGYA RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 2017-19 43 UNICEF FUNDING NEEDS 2019 Monsoon rainclouds loom overhead as Mohamed Amin (facing camera centre) and other family members rebuild their shelter which was destroyed during heavy monsoon rains on the night of July 6 2019. In the space of 25 days in July, authorities in the vast Rohingya camps had to assist over 5,700 refugee households with damaged shelters. -

Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh

remote sensing Article Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh Mohammad Mehedy Hassan 1,*, Audrey Culver Smith 1, Katherine Walker 1 ID , Munshi Khaledur Rahman 2 and Jane Southworth 1 1 Department of Geography, University of Florida, 3141 Turlington Hall, P.O. Box 117315, Gainesville, FL 32611-7315, USA; audreyculver@ufl.edu (A.C.S.); kqwalker@ufl.edu (K.W.); jsouthwo@ufl.edu (J.S.) 2 Department of Geography, Virginia Tech, 115 Major Williams Hall, 220 Stanger Street, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: mehedy@ufl.edu; Tel.: +1-352-745-9364 Received: 6 March 2018; Accepted: 25 April 2018; Published: 30 April 2018 Abstract: Following a targeted campaign of violence by Myanmar military, police, and local militias, more than half a million Rohingya refugees have fled to neighboring Bangladesh since August 2017, joining thousands of others living in overcrowded settlement camps in Teknaf. To accommodate this mass influx of refugees, forestland is razed to build spontaneous settlements, resulting in an enormous threat to wildlife habitats, biodiversity, and entire ecosystems in the region. Although reports indicate that this rapid and vast expansion of refugee camps in Teknaf is causing large scale environmental destruction and degradation of forestlands, no study to date has quantified the camp expansion extent or forest cover loss. Using remotely sensed Sentinel-2A and -2B imagery and a random forest (RF) machine learning algorithm with ground observation data, we quantified the territorial expansion of refugee settlements and resulting degradation of the ecological resources surrounding the three largest concentrations of refugee camps—Kutupalong–Balukhali, Nayapara–Leda and Unchiprang—that developed between pre- and post-August of 2017. -

Case Study 1 CXB

Information and Feedback Centres Improving Accountability to Rohingya Refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh Improving Accountability to the Rohingya Refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh 1 This is one of a series of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement and accountability activities as part of the larger humanitarian response to the Rohingya refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, from September 2017 to December 2019. Editing: Rain Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design: Azad/Drik The opinions expressed in this case study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF. Extracts from this case study may be freely reproduced provided that due acknowledgement is given to the source and to UNICEF. © United Nations Children’s Fund, July 2020 This is one of a series of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement ThUNICEFis is one Ba ngladesof a seriesh of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement andBSL accountOffice Complability exactivities, 1 Minto as R partoad of the larger humanitarian response to the Rohingya refugee crisis in Coandx ’saccount Bazar, abiliBangladesh,ty activities from as Septemberpart of the larger 2017 tohumani Decembertarian 2response019. to the Rohingya refugee crisis in CoDhakax’s B 10azar00,, BBangladesh,angladesh from September 2017 to December 2019. Author: Dr. Hakan Ergül 2 INFORMATION AND FEEDBACK CENTRES Editing: Rain Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design:Editing: RainAzad/Drik Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design: Azad/Drik The opinions expressed in this case study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies orThe vie opinionsws of UNICEF expressed. -

FOREWORD in 2017, Asia and the Pacific Was Home to More Than 60 Per Cent of the World’S Population

REGIONAL SUMMARIES FOREWORD In 2017, Asia and the Pacific was home to more than 60 per cent of the world’s population. With some 4.4 billion people, the region is an engine for global development, characterized by economic growth, rising living standards, and people on the move seeking new opportunities. However, in 2017, millions of people were not following this upward trajectory. The region hosted 9.5 million people of concern to UNHCR, including 4.2 million refugees, 2.7 million IDPs, and an estimated 2.2 million stateless persons. Of the total population of concern to UNHCR, half were children; more than half were women and girls; and many had no nationality, documentation or place to call home. The long-standing tradition of hospitality towards many displaced people remained strong across the region. This was demonstrated by the remarkable response of Bangladesh, which kept its borders open to nearly 655,000 stateless refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar. The influx dramatically altered the operational context for UNHCR in Bangladesh. As a result of the urgent humanitarian needs, UNHCR ramped up its capacity in support of refugees, the Government and local communities generously hosting them. The solutions to this crisis lie in Myanmar, and it is there that the search must start for them. The efforts needed to enable the voluntary and sustainable repatriation of refugees failed to materialize in 2017, and they must begin with humanitarian access for UNHCR. Preserving the right of return, however, remained a central priority for UNHCR and Asia and the Office welcomed the commitments made by Bangladesh and Myanmar on dignified, safe, and voluntary repatriation in 2017. -

Weekly Situation Report 3

Weekly Situation Report # 2 Date of issue: 8 November 2017 Period covered: 1 to 7 November 2017 Location: Bangladesh Emergency type: Arrival of Rohingya population from Myanmar following conflict in Rakhine state 609 000 300 000 105 1727 1.2 million new arrivals refugees from Myanmar children over 1 year of age people targeted for in Bangladesh who arrived previously vaccinated with oral cholera humanitarian assistance in B angladesh vaccine (58% of target at end of day 3 of 6-day campaign) KEY HIGHLIGHTS As of 6 November 2017, the cumulative number of new arrivals in all sites (Ukiah, Teknaf, Cox’s Bazar and Ramu) was 609 0001. This number includes over 329 000 arrivals in Kutupalong Balukhali expansion site, 230 000 in other camps and settlements, and 46 000 arrivals in host communities. According to data generated by WHO’s disease early warning and response system (EWARS), a total of 245 389 consultations were provided to the new arrivals and other vulnerable populations between 25 August to 4 November 2017. A total of 412 suspected cases of measles have been reported through EWARS. Case investigation/finding is ongoing. The preliminary results of a recent inter-agency assessment conducted in Kutupalong refugee camp from 22 to 28 October 2017 shows that severe acute malnutrition rates are running at 7.5% (well above emergency thresholds). The second phase of an oral cholera vaccination campaign started on 4 November. Around 180 000 children aged between one and five years will be given a second dose of oral cholera vaccine for added protection, and 210 000 children under five years of age will be given oral polio vaccine (bOPV). -

Persecution of the Rohingya Muslims

OCTOBER 2015 PERSECUTION OF THE ROHINGYA MUSLIMS: IS GENOCIDE OCCURRING IN MYANMAR’S RAKHINE STATE? A LEGAL ANALYSIS PREPARED FOR FORTIFY RIGHTS ALLARD K. LOWENSTEIN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS CLINIC, YALE LAW SCHOOL OCTOBER 2015 PERSECUTION OF THE ROHINGYA MUSLIMS: IS GENOCIDE OCCURRING IN MYANMAR’S RAKHINE STATE? A LEGAL ANALYSIS Prepared by the ALLARD K. LOWENSTEIN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS CLINIC, YALE LAW SCHOOL for FORTIFY RIGHTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper was written by Alina Lindblom, Elizabeth Marsh, Tasnim Motala, and Katherine Munyan of the Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic at Yale Law School. The team was supervised and the paper edited by Professor James Silk, director of the Lowenstein Clinic, and Soo-Ryun Kwon, formerly the Robert M. Cover - Allard K. Lowenstein Fellow in International Human Rights at Yale Law School. Former clinic member Veronica Jordan-Davis contributed to the initial research for the paper. The team would like to thank the students in the Fall 2015 Lowenstein Clinic for helping to check the paper’s citations. CONTENTS I. SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 II. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................4 III. HISTORY OF HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES AGAINST ROHINGYA IN MYANMAR ...........................................................................................5 A. ROHINGYA UNDER MILITARY RULE: FROM MYANMAR’S INDEPENDENCE THR OUGH 2011 ..............................................................5 -

Effectiveness of an Integrated Care Package for Refugee Mothers and Children: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

JMIR RESEARCH PROTOCOLS Al Azdi et al Protocol Effectiveness of an Integrated Care Package for Refugee Mothers and Children: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Zunayed Al Azdi1, BSc, MPH; Khaleda Islam1, MBBS, MPH, MMEd; Muhammad Amir Khan2, DHA, MPH, PhD; Nida Khan2, MSc, MSPH; Amna Ejaz2, MS; Muhammad Ahmar Khan2, MBBS; Azza Warraitch2, MPhil; Ishrat Jahan1, BDS, MPH; Rumana Huque1, PhD 1ARK Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Association for Social Development, Lahore, Pakistan Corresponding Author: Zunayed Al Azdi, BSc, MPH ARK Foundation Suite C-4, House No. 6 Road No. 109, Gulshan-2 Dhaka, 1212 Bangladesh Phone: 880 1711455670 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Thousands of Rohingya refugee mothers at the world's largest refugee camp located in Bangladesh are at risk of poor mental health. Accordingly, their children are also vulnerable to delayed cognitive and physical development. Objective: The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of an integrated care package in reducing the prevalence of developmental delays among children aged 1 year and improving their mothers' mental health status. Methods: This is a parallel, two-arm, single-blind, cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT). A total of 704 mother-child dyads residing at the Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, will be recruited from 22 clusters with 32 mother-child dyads per cluster. In the intervention arm, an integrated early childhood development and maternal mental health package will be delivered every quarter to mothers of newborns by trained community health workers until the child is 1 year old. Our primary outcome is a reduction in the prevalence of two or more childhood developmental delays of infants aged 1 year compared to the usual treatment. -

Coronavirus Closes in on Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh's

Boise State University ScholarWorks University Author Recognition Bibliography: 2020 The Albertsons Library 4-20-2020 Coronavirus Closes in on Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh’s Cramped, Unprepared Camps Saleh Ahmed Boise State University Academic rigor, journalistic flair Nary a mask in sight at a market area in Bangladesh’s Kutupalong refugee camp for Rohingya, Ukhia, March 24, 2020. Suzauddin Rubel/AFP via Getty Images Coronavirus closes in on Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh’s cramped, unprepared camps April 20, 2020 2.05pm EDT Coronavirus is spreading quickly in densely populated Bangladesh, despite a Author nationwide shutdown put in place a month ago. This preventive measure has proven challenging to implement due to lack of awareness of the coronavirus and the absence of a social safety net. Extreme poverty Saleh Ahmed also forces many Bangladeshis to keep working and looking for food despite the risks. Assistant Professor, School of Public Bangladesh had 2,948 confirmed COVID-19 cases as of April 20. Service, Boise State University The disease has not yet spread into the refugee camps that house the Rohingya Muslims who fled ethnic violence in Myanmar in 2017, according to a recent update from the humanitarian organizations that work in the camps. But an outbreak in the overcrowded camps is almost certain to come eventually – and when it does, experts say, the damage could be severe. Crisis response in the camps Even in normal times people in refugee camps often struggle to survive, living as they do with minimal resources, food and housing. I saw this grim reality with my own eyes when I visited the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh – my home country – in 2017 and 2018. -

Factual Findings & Legal Analysis Report

DOCUMENTING ATROCITY CRIMES COMMITTED AGAINST THE ROHINGYA IN MYANMAR’S RAKHINE STATE The Public International Law & Policy Group’s 2018 Human Rights Documentation Mission — FACTUAL FINDINGS & LEGAL ANALYSIS REPORT December 2018 © Copyright Public International Law and Policy Group, 2018 The Public International Law & Policy Group encourages the use of this document. Any part of the material may be duplicated with proper acknowledgment. Cover photo courtesy of Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala. All of my interactions with the refugees were polite, generous and positive. This never ceased to amaze me, given the circumstances under which I was meeting them. The Rohingya are a pervasively persecuted minority, accustomed to being aliens in a land so hostile to them that the agents of law and order regularly brutalized them. Even the Rohingyas’ neighbors regularly betrayed and victimized them. I would have thought they’d have earned the sort of distrust, cynicism, and fear that would have caused them to refuse to speak to any strangers, let alone those seeking to ask personal questions about their repression. - Quote from an investigator They cried from the pain of having lost loved ones, from the anguish of watching their houses, businesses and animals burn, from the horror of stepping over bodies on the banks of the river to climb on to the ferry that would take them away from a place they unfailingly called their “homeland.” Most often, though, people started to cry when they described the injustice of what they had experienced. One man, who was in a refugee camp for the third time in his life because of government sponsored or tolerated repression (1978, 1991, 2017) said, “We did nothing to them. -

Highlights: Developments

Highlights: Camp Conditions: • The coronavirus pandemic is aggravating tensions between Rohingya refugees and host communities in Bangladesh, with local NGOs calling for the emergency response to better include host communities, not just Rohingya in the camps. • Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), has opened another Covid-19 isolation and treatment centre in the Nayapara refugee camp. • Leaders of local NGOs in Cox’s Bazar have expressed concern that the Inter Sectoral Management Group is shutting out local NGOs and local government bodies from the emergency response planning and funding. Access to Territory: • Twenty-six Rohingya refugees, who last week had been feared drowned while trying to swim ashore close to the Malaysian resort island of Langkawi, have been found alive, hiding in the vegetation on a nearby islet and are now being detained, according to a senior coastguard official. High-level Statements: • ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has expressed appreciation for Bangladesh’s strong support for the ICC’s independent mandate on justice matters, the international criminal justice system and the Rome Statute. Developments: How to Elevate Rohingya Women’s Voices Amid a Crackdown on the Coronavirus The National Interest (August 2) [op-ed] For decades, the Burmese military has used sexual violence as a weapon of war against the Rohingya. But Rohingya women’s vulnerability to sexual violence and abuse does not end at the Burmese border. Coronavirus conditions are further exacerbating barriers to access to medical care and are further impeding women’s ability to participate in decision-making within the camps. As a result, women are experiencing more gender-based violence, more behavior-policing, and more restrictions on their mobility.