Governing Sustainable Agriculture : a Case Study of the Farming of Highly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Unfair" Trade?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid Working Paper Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade? NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39 Provided in Cooperation with: New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington Suggested Citation: Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid (2005) : Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade?, NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/66072 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

The New Zealand Azette

Issue No. 110 • 2423 The New Zealand azette WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 25 JULY 1991 Contents Vice Regal 2424 Government Notices 2424 Authorities and Other Agencies of State Notices 2442 Land Notices 2443 Regulation Summary 2459 General Section 2460 Using the Gazette The New Zealand Gazette, the official newspaper of the Closing time for lodgment of notices at the Gazette Office is Government of New Zealand, is published weekly on 12 noon on the Tuesday preceding publication (except for Thursday. Publishing time is 4 p.m. holiday periods when special advice of earlier closing times Notices for publication and related correspondence should be will be given) . addressed to: Notices are accepted for publication in the next available issue, Gazette Office, unless otherwise specified. Department of Internal Affairs, P 0 . Box 805, Notices being submitted for publication must be reproduced Wellington. copies of the originals. Dates, proper names and signatures are Telephone (04) 495 7200 to be shown clearly. A covering instruction setting out require Facsimile (04) 499 1865 ments must accompany all notices. or lodged at the Gazette Office, Seventh Floor, Dalmuir Copy will be returned unpublished if not submitted in House, 114 The Terrace, Wellington. accordance with these requirements. 2424 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 110 Availability Shop 3, 279 Cuba Street (P.O. Box 1214), Palmerston North. The New Zealand Gazette is available on subscription from GP Publications Limited or over the counter from GP Books Cargill House, 123 Princes Street, Dunedin. Limited bookshops at: Housing Corporation Building, 25 Rutland Street, Auckland. Other issues of the Gazette: 33 Kings Street, Frankton, Hamilton. -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question......................... -

Chronologies Put Together from Various Persons Evidence Shows That Jane Charles Chronology Was Dismissed After I Had Named Her

Event references 1957-1961 Wells works for the Public Service: Inland Revenue• Department, Electricity Department, Department of External Affairs (seconded to Secretariat of South East Neil Wells C.V. Asia Treaty Organisation 1959). 1962 to 1992 Harvey MacHarman Ayer Harvey CV 1961-1966: NZ Police Neil Wells C.V. 1966-1967 Wells G Baker Real Estate: Administration Manager. Neil Wells C.V. 1967-1970: Wells employed New Zealand Newspapers Ltd: National Sales Executive, Neil Wells C.V. New Zealand Home Journal. 1970-1971: Wells employed J Inglis Wright Ltd, accredited advertising agency: Assistant Neil Wells C.V. Media Manager. 1971-1974 Wells employed at MacHarman Associates Ltd, accredited advertising agency: Media Manager 1971, General Neil Wells C.V. Manager 1972. With Bob Harvey 1971-1973 Wells VOLUNTARY & COMMUNITY WORK.Councillor, Society for the Neil Wells C.V. Prevention of Cruelty of Animals, Auckland. 1973-1978: Wells VOLUNTARY & COMMUNITY WORK President, Society for the Neil Wells C.V. Prevention of Cruelty of Animals, Auckland. 16/12/1973 Sunday news item news 16 dec 73 1974 Wells Barron Craig Associates Ltd, accredited Neil Wells C.V. advertising agency: Auckland Manager. 1974-1978 Wells Vision Advertising (NZ) Ltd, accredited advertising agency: Managing Director and principal Neil Wells C.V. shareholder. 5/09/1975 Neil Wells as chairman of the SPCA Auckland signs the constitution of the Royal federation of New Zealand societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals 218546 - THE ROYAL NEW ZEALAND SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION http://www.societies.govt.nz OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS INCORPORATED 1974-1993 Wells VOLUNTARY & COMMUNITY WORK Councillor, Royal New Zealand Neil Wells C.V. -

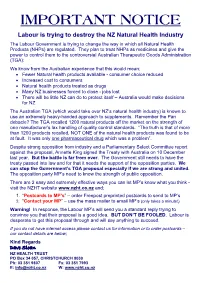

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour Is Trying to Decimate the NZ Health Products Industry

IMPORTANT NOTICE IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry Labour is trying to decimate the NZ Health Products Industry The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to & medical devices are regulated. They plan to treat them as medicines and give the power to control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Fewer products available - consumer choice reduced • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Unnecessary bureaucracy and cost • Increased cost to consumers • Increased cost to consumers • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Natural health products & medical devices all controlled like drugs • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s health products industry) is known to use an extremely heavy-handed approach. -

Enlarged Europe, Shrinking Relations? the Impacts of Hungary's Eu Membership on the Development of Bilateral Relations Between New Zealand and Hungary

ENLARGED EUROPE, SHRINKING RELATIONS? THE IMPACTS OF HUNGARY'S EU MEMBERSHIP ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF BILATERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN NEW ZEALAND AND HUNGARY ________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in European Studies in the University of Canterbury by Adrienna Ember University of Canterbury 2008 CONTENT Page Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 2 Abbreviations 3 List of Figures 5 List of Tables 6 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 8 1.2 Problem setting 15 1.3 Empirical literature 16 1.4 Objectives and research questions 19 1.5 Theoretical Framework 23 1.6 Methodology and Limitations 26 1.7 Chapters Overview 29 1.8 Summary 31 Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORY 2.1 Introduction 32 2.2 Review of Empirical Literature 33 2.2.1. Introduction 33 2.2.2 Literature on Relations between New Zealand and the EU 34 2.2.3 Literature on Relations between Hungary and the EU 40 2.2.4 Literature on New Zealand and Hungary within the Context of the EU 52 2.2.5 Summary of Empirical Literature 55 2.3 Theoretical Framework 56 2.3.1 Introduction 56 2.3.2 Small State Theory 57 2.3.2.1 Relevance and Development of ‘Small States’ Studies in Europe 57 2.3.2.2 Can Smallness be Defined? 60 2.3.2.3 Milestones in the Small State Literature 63 2.3.2.4 Critiques of Small State Theory 68 ii Page 2.3.2.5 The Applicability of Small State Theory for New Zealand 74 and Hungary 2.3.3 Theory on the Role of Ethnic Networks in International Trade 78 2.3.3.1 Development of Theory -

Walking Access Across Private Land: Behind the Soundbites

Walking Access across Private Land: Behind the Soundbites Pete McDonald December 2004 ‘Labour will develop a public access strategy, includ- ing the extension of the Queen’s Chain and the provision of rural and urban walkways, to ensure New Zealanders have ready and free access to our waterways, coastline and natural areas.’ From Labour’s Conservation Policy 2002, part of Labour’s 2002 election manifesto. A PDF copy of this essay is available from: Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 1. Federated Farmers in Denial........................................................................................... 5 The Acland Report and the Loss of Access ................................................................... 6 No Confidence in the Evidence .................................................................................... 7 Weakening Social Conventions and Changing Access Aspirations ................................ 7 What About Tenure Review? ........................................................................................ 9 2. Legislation and Goodwill ............................................................................................... 10 Beneficial Adjustment of Property Rights ................................................................... 10 Selective Goodwill ..................................................................................................... 11 Goodwill and Access Trusts ...................................................................................... -

This Is New Zealand Reflects on Who We Thought We Were, Who We Think We Are

curated by Robert Leonard and Aaron Lister, with Moya Lawson First, a Word from the CuratorsRobert Leonard . .and . Aaron Lister Teasing out connections between images, ideology, and identity, our exhibition This Is New Zealand reflects on who we thought we were, who we think we are. Taking a critical look at stories we’ve told ourselves and others, it asks: Who and what have been included and excluded? And who is this mythical ‘we’? This Is New Zealand emerged out of our thinking about New Zealand’s participation in the Venice Biennale. New Zealand has been going to the Biennale since 2001, and it looms large for our art scene. The Biennale is the world’s largest, most important, and longest-running regular contemporary-art mega-show, and our participation declares our desire to be ‘international’, to be part of the wider art discussion. However, some of the artists we have sent to Venice have taken it as an opportunity to tackle old questions Lisa Reihana (sunglasses) and the Governor-General, of national identity, riffing on the Biennale’s Her Excellency the Rt. Hon. Dame Patsy Reddy (cloak), arrive in style on the Disdotona—a giant old-school national-pavilion structure. Our gondola, propelled by eighteen rowers from the show includes three examples from Venice. Canottieri Querini Rowing Club—for the opening of Reihana’s exhibition Emissaries, New Zealand Michael Stevenson’s 2003 project This Is pavilion, Venice Biennale, 10 May 2017. ‘It was the Trekka looks like a belated trade display wonderful coming down the Grand Canal. I felt like a queen’, said Reihana. -

Download History Book

THE COMMUNITY TRUST OF MID & SOUTH CANTERBURY INC The first 25 years of the Community Trust of Mid and South Canterbury 1988 – 2013 1 Writer Carol Angland Published by Community Trust of Mid and South Canterbury Community House 27 Strathallan Street, Timaru ISBN 978 -0-473-31744-7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic or mechanical, through reprography, digital transmission, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. © 2015 E&OE Without community service, we would not have a strong quality of life. It’s important to the person who serves as well as the recipient. It’s the way in which we ourselves grow and develop. - Dorothy Height 3 4 Contents Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................................................................................6 Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................7 How It All Began .......................................................................................................................................................................................9 Trust Bank South Canterbury Community Trust ..................................... 23 Governance and Management ...............................................................................................................35 -

Mixing Business with Politics? the Role and Influence of the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum

Mixing Business with Politics? The Role and Influence of the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum By Simon Le Quesne A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations 2011. Table of Contents Abstract i Acknowledgements ii Abbreviations iii Introduction 1 Chapter One: Conceptualising the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum 9 Chapter Two: The Genesis of the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum 27 Chapter Three: The Form and Modalities of the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum 49 Chapter Four: The Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum and trans-Tasman Relations (2004 – 2010) 81 Chapter Five: Conclusion. The Role and Influence of the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum 111 Figure: ANZLF Participation by Group 2004-2009 56 Appendices 116 Appendix One - List of interviewees 116 Appendix Two - Standard questions asked of every participant 120 Appendix Three - Regular attendees 121 Appendix Four - Challenges to improve trans-Tasman labour market outcomes 122 Appendix Five - Trans-Tasman Outcomes Implementation Group 123 Bibliography 124 Abstract Since 2004, the Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum (ANZLF), an annual bilateral business-led Forum, has facilitated the engagement of high level state and non-state Australian and New Zealand actors in debate, unofficial dialogue, networking, information and idea exchange. Yet very little is known about the event, who participates and what the ANZLF produces. Drawing on extensive interviews with key participants and organisations, this thesis examines the Forum’s genesis, its form and modalities, and the substance of the meetings. -

Turning Gain Into Pain

TURNING GAIN INTO PAIN NEW ZEALAND BUSINESS ROUNDTABLE MAY 1999 The New Zealand Business Roundtable is an organisation of chief executives of major New Zealand businesses. The purpose of the organisation is to contribute to the development of sound public policies that reflect overall New Zealand interests. First published in 1999 by New Zealand Business Roundtable, PO Box 10–147, The Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand http://www.nzbr.org.nz ISBN 1–877148–47–4 ã 1999 edition: New Zealand Business Roundtable ã Text: as acknowledged Production by Daphne Brasell Associates Ltd, Wellington Printed by Astra Print Ltd, Wellington FOREWORD This collection of speeches, submissions and articles is the fourteenth in a series produced by the New Zealand Business Roundtable (NZBR). The previous volumes in the series were Economic and Social Policy (1989), Sustaining Economic Reform (1990), Building a Competitive Economy (1991), From Recession to Recovery (1992), Towards an Enterprise Culture (1993), The Old New Zealand and the New (1994), The Next Decade of Change (1994), Growing Pains (1995), Why Not Simply the Best? (1996), MMP Must Mean Much More Progress (1996), Credibility Promises (1997), The Trouble with Teabreaks, (1998) and Excellence Isn't Optional (1998). The material in this volume is organised in six sections: economic directions; the public sector; industry policy and regulation; education and the labour market; social policy; and miscellaneous. It includes a paper by Bryce Wilkinson, consultant to the NZBR. A full list of NZBR publications is also included. R L Kerr EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CONTENTS ECONOMIC DIRECTIONS 1 1 TURNING GAIN INTO PAIN 3 Speech by Douglas Myers to the Wellington Regional Chamber of Commerce, November 1998 2 GLOBALISATION, ASIA AND IMPLICATIONS FOR NEW ZEALAND 11 Speech by Roger Kerr to a Greenwich Financial Services Client Function, December 1998. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE Labour is trying to destroy the NZ Natural Health Industry The Labour Government is trying to change the way in which all Natural Health Products (NHPs) are regulated. They plan to treat NHPs as medicines and give the power to control them to the controversial Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA): We know from the Australian experience that this would mean; • Fewer Natural health products available - consumer choice reduced • Increased cost to consumers • Natural health products treated as drugs • Many NZ businesses forced to close - jobs lost • There will be little NZ can do to protect itself – Australia would make decisions for NZ The Australian TGA (which would take over NZ’s natural health industry) is known to use an extremely heavy-handed approach to supplements. Remember the Pan debacle? The TGA recalled 1200 natural products off the market on the strength of one manufacturer’s lax handling of quality control standards. “The truth is that of more than 1200 products recalled, NOT ONE of the natural health products was found to be at fault. It was only one pharmaceutical drug which was a problem”. Despite strong opposition from industry and a Parliamentary Select Committee report against the proposal, Annette King signed the Treaty with Australia on 10 December last year. But the battle is far from over. The Government still needs to have the treaty passed into law and for that it needs the support of the opposition parties. We can stop the Government’s TGA proposal especially if we are strong and united. The opposition party MP’s need to know the strength of public opposition.