Shipping Migrants in the Age of Steam: the Rise and Rise of the Messageries Maritimes C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Waves on the Seven Seas

4 Waves on Waves – Long Waves on the Seven Seas Anttiheikki Helenius Abstract Kondratieff waves are an interesting subject of study and describe present global economic developments. The Global Financial Crisis of 2009 and the present economic situation have parallels with the Great Depression of the 1930s. Twice-in-a-century events are occurring again. On the other hand, many important innovations have been introduced during the last decades. These innovations have changed people's lives in a revolution- ary manner and have contributed very positively to the global development. Study of the development of seafaring supports the claim of the existence of Kondratieff waves. Important innovations and milestones of development of seafaring coincided with the upswing phases of these waves. Moods of different eras manifest also in composition of shipping fleets and flotillas. One needs new creative approaches to solve global challenges. The study of long waves allows compelling insights and provides timeless wisdom for the study of economics. Keywords: Kondratieff waves, long waves, global financial crisis, maritime economics, economic forecasting, philosophy of science and economics, Schum- peterian economics, time preference of consumption, Hayekian economics, cruise industry. General Introduction to the Long Waves and to the Subject of This Article For my Doctoral thesis in Economics I studied the theory of Kondratieff waves. I used that theory in the practical context when analyzing the air transportation (Helenius 2003). A special vindication could be established for using a long waves approach for analyzing air transportation. Also I have used the long waves approach in recent conference papers (Idem 2009, 2010). -

1840/85 the Mail Service in the North Africa Ports Alexandria, Tunis, Algiers, Bone, Philippeville, Oran, Tanger and Tripoli of Barbery

1840/85 The mail service in the North Africa ports Alexandria, Tunis, Algiers, Bone, Philippeville, Oran, Tanger and Tripoli of Barbery INTRODUCTION: During the nineteenth century the ship traffic knew an unprecedented intensity, encouraged by the arrival of the steam navigation that was, by then, able to ensure not only more security but even shorter journeys and a more certain length of them. Regarding the Mediterranean sea, a decisive turning points were the choice of Suez, still before the channel opening, as the reference port for East Indies traffics as well as the the raising of the colonial politics with the French occupation of Algerie and the first Italian interest shown towards Tunisie and Libya, together with the strengthening of traffics with the declining Ottoman Empire. The Egypt, particularly, under the guide of the governor Mohamed Ali Pasha to whom the Sublime Porte had recognized the vice roy (Khedivè) title with a large self-government, met a period a great economic rise that supported the settling of a large foreign Community, about 60.000 people, leading some of the most important European countries to open their post offices and establish steam navigation companies. SCOPE: This collection has the objective of offering a view of the mail system, in years 1840/85, in the Egyptian port of Alexandria, according to the following list of steam navigation lines. PLAN OF COLLECTION I-Alexandria 1. British Lines: 1a ALEXANDRIA-MALTA-GIBRALTAR-SOUTHAMPTON by “Peninsular & Oriental Co.”; 1b ALEXANDRIA-MALTA-MARSEILLE known as “Marseille Line” by “Peninsular & Oriental Co”, working until 1870; 1c ALEXANDRIA–BRINDISI “India bag” by “Peninsular & Oriental Co. -

Wilfred Sykes Education Corporation

Number 302 • summer 2017 PowerT HE M AGAZINE OF E NGINE -P OWERED V ESSELS FRO M T HEShips S T EA M SHI P H IS T ORICAL S OCIE T Y OF A M ERICA ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Messageries Maritimes’ three musketeers 8 Sailing British India An American Classic: to the Persian steamer Gulf 16 Post-war American WILFRED Freighters 28 End of an Era 50 SYKES 36 Thanks to All Who Continue to Support SSHSA July 2016-July 2017 Fleet Admiral – $50,000+ Admiral – $25,000+ Maritime Heritage Grant Program The Dibner Charitable The Family of Helen & Henry Posner, Jr. Trust of Massachusetts The Estate of Mr. Donald Stoltenberg Ambassador – $10,000+ Benefactor ($5,000+) Mr. Thomas C. Ragan Mr. Richard Rabbett Leader ($1,000+) Mr. Douglas Bryan Mr. Don Leavitt Mr. and Mrs. James Shuttleworth CAPT John Cox Mr. H.F. Lenfest Mr. Donn Spear Amica Companies Foundation Mr. Barry Eager Mr. Ralph McCrea Mr. Andy Tyska Mr. Charles Andrews J. Aron Charitable Foundation CAPT and Mrs. James McNamara Mr. Joseph White Mr. Jason Arabian Mr. and Mrs. Christopher Kolb CAPT and Mrs. Roland Parent Mr. Peregrine White Mr. James Berwind Mr. Nicholas Langhart CAPT Dave Pickering Exxon Mobil Foundation CAPT Leif Lindstrom Peabody Essex Museum Sponsor ($250+) Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ferguson Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey Lockhart Mr. Henry Posner III Mr. Ronald Amos Mr. Henry Fuller Jr. Mr. Jeff MacKlin Mr. Dwight Quella Mr. Daniel Blanchard Mr. Walter Giger Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Jack Madden Council of American Maritime Museums Mrs. Kathleen Brekenfeld Mr. -

British India Steam Navigation Company

British India Steam Navigation Company Operator of passenger and cargo services in Indian waters, the Bay of Bengal, the Gulf and to Japan, Australia and East Africa as well as ‘Home Lines’ from the UK Pre-P&O Years The founder of the British India Steam Navigation Company (BI) was William Mackinnon (b.1823-d.1893) who, in partnership with William Mackenzie (ca.1810-d.1853) operated as a general merchant near Calcutta. In the mid- 1850s Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Company secured the East India Company's mail contract between Calcutta and Rangoon and founded the Calcutta & Burmah Steam Navigation Company Ltd, registered in Glasgow in 1856, with a capital of £35,000. Within five years of its foundation, the company had expanded considerably: from Burma, its ships were serving Penang and Singapore, while dozens of small ports along the Indian coast were being opened up to large-scale traffic by its service between Calcutta and Bombay. A mail contract to cover the whole of this route was being negotiated, and a similar contract up and down the Persian Gulf was being contemplated by the Government. In 1861 Mackinnon raised £400,000 to establish the British India Steam Navigation Company Ltd, and ordered six larger ships. The new company, which absorbed the Calcutta & Burmah Company, was registered in Scotland in 1862. The original Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Company in Calcutta continued to exist and operate as BI’s managing agents, a function which they were to fulfil for nigh on a hundred years. BI secured a network of mail contract services – Bombay/Karachi, Bombay/Gulf, Bombay/Calcutta and Madras/Rangoon – which became the backbone of its operations. -

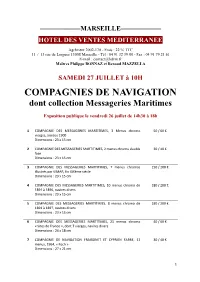

COMPAGNIES DE NAVIGATION Dont Collection Messageries Maritimes

——————MARSEILLE—————— HOTEL DES VENTES MEDITERRANEE Agrément 2002-170 - Frais : 22 % TTC 11 / 13 rue de Lorgues 13008 Marseille - Tél : 04 91 32 39 00 - Fax : 04 91 79 21 61 E-mail : [email protected] Maîtres Philippe BONNAZ et Renaud MAZZELLA SAMEDI 27 JUILLET à 10H COMPAGNIES DE NAVIGATION dont collection Messageries Maritimes Exposition publique le vendredi 26 juillet de 14h30 à 18h 1 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 3 Menus chromo 50 / 60 € vierges, années 1900 Dimensions : 23 x 15 cm 2 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 2 menus chromo double 30 / 40 € face Dimensions : 23 x 15 cm 3 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 7 menus chromos 150 / 200 € illustrés par VIMAR, fin XIXème siècle Dimensions : 23 x 15 cm 4 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 10 menus chromo de 180 / 200 € 1891 à 1896, navires divers Dimensions : 23 x 15 cm 5 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 8 menus chromo de 180 / 200 € 1891 à 1897, navires divers Dimensions : 23 x 15 cm 6 COMPAGNIE DES MESSAGERIES MARTITIMES, 21 menus chromo 40 / 60 € « Sites de France », dont 7 vierges, navires divers Dimensions : 24 x 18 cm 7 COMPAGNIE DE NAVIGATION FRAISSINET ET CYPRIEN FABRE, 12 30 / 40 € menus, 1964, « Foch » Dimensions : 27 x 21 cm 1 8 COMPAGNIE MARITIME DES CHARGEURS REUNIS, 14 menus carte- 30 / 40 € postale « régions de France », années 50, « Brazza » Dimensions : 27 x 13 cm 9 COMPAGNIE MARITIME DES CHARGEURS REUNIS, 12 menus carte- 30 / 40 € postale « beaux paysages de France», années 50, navires divers Dimensions : 27 x 13 cm 10 COMPAGNIE MARITIME DES -

Display to Society of Postal Historians FRENCH MESSAGERIES

Display to Society of Postal Historians at London 2010 Exhibition on 6.5.10 FRENCH MESSAGERIES IMPERIALES / MARITIMES MAIL PAQUEBOT ITINERARIES TO, FROM, AND WITHIN THE FAR EAST 1862 – 1880 Far East Mail Ship Itineraries Volume 2 © by Lee C. Scamp This display is a little different than what you typically see: my new book is discussed and illustrated Some of you have probably seen my previous book, Far East Mail Ship Itineraries, Vol. 1, P&O: An update and augmentation of Reg Kirk’s P&O Lines to the Far East My Vol. 2 is a similar effort for the French Paquebot Itineraries To, From, and Within The Far East During 1862 - 80 period there was extensive expansion of the ocean mail service to and within the Far East In 1862 the French began operation of a mail packet line to Hong Kong in direct competition with the British P&O The MI Line was extended to Shanghai the next year, A branch service to Yokohama began in 1865, first via Shanghai, and then later directly from Hong Kong When the Suez Canal was opened in 1869, the French Line (unlike the P&O) immediately began direct service between Marseille and the Far East via that canal, Messageries Imperiales (MI) became the Messageries Maritimes (MM) in 1871. My good friend, and fellow SPH member, Dr. Andrew Cheung challenged me to have this book completed in time for publication at the London 2010 show Book has been completed (copy for viewing here), and should be published in next few months Book is over 400 pages with over 300 illustrations of covers, most in color, and other postal -

Shipping and Commerce Between France and Algeria, 1830-1914

Marrying the Orient and the Occident: Shipping and Commerce between France and Algeria, 1830-1914 THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Perry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Master's Examination Committee: Professor Alice Conklin, Advisor Professor Christopher Otter, Advisor Professor David Hoffmann, Advisor Copyright by John Perry 2011 Abstract Steam technology radically transformed world shipping in the nineteenth century. Shipping lines established fast and predictable schedules that linked the far reaches of the world to Europe. These sea routes also went hand-in-hand with European imperial expansion; regular, reliable communications between colony and mother country cemented imperial control. To analyze these links, I explore the establishment and operation of shipping lines between France and its most prized colony, Algeria, between 1830 and 1914. The French state fostered this trade through generous subsidies, eventually declaring a monopoly on Franco-Algerian trade in 1889. Far from being a simple story of the French state playing a large role in the affairs of private enterprise, I examine the tensions between political and economic motives to justify these steamship services. These tensions underlying the justifications of linking France and its empire with French ships reveal that the day-to-day operations of these shipping lines were more complex, and more fraught, than previously imagined. ii Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family who supported my ambition to go to graduate school. iii Acknowledgments Academic research is a collaborative effort. -

Interoceanic Canals and World Seaborne Trade: Past, Present and Future

ARSOM-KAOW The Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences Permanent InternationalAssociation for Navigation Congresses Port of The World Association for Waterbome A Antwerp Transport lnfrastructure International Colloquium INTEROCEANIC CANALS AND WORLD SEABORNE TRADE: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE (Brussels, 7-9 June 2012) Guest Editors: J. CHARLIER, C. DE MEYER & H. PAELINCK Financially supported by FONDATION beis po Sefacil tnrs LOCIBT10UC • PonTUA!AC • MARlfl"'C LA Ulf.ITil CHUCHUDE The Belgian Science Policy Office Fondation Sefacil Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique 2015 ACADEMIE ROYALE KONINKLIJKE ACADEMIE DES VOOR SCIENCES o'ÜUTRE-MER ÛVERZEESE WETENSCHAPPEN Avenue Louise 231 Louizalaan 231 B-1050 Bruxelles (Belgique) B-1050 Brussel (België) Tél. 02.538.02.1 1 Tel. 02.538.02. 11 Fax 02.539.23.53 Fax 02.539.23.53 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.kaowarsom.be Web: www.kaowarsom.be ISBN 978-90-756-5257-4 D/2015/0 149/4 CONTENTS J. CHARLIER, C. DE MEYER & H. PAELINCK. - Introduction ........ 5 lnteroceanic Canals in Context G. CAUDE. - Le röle de l'AIPCN dans la conception des projets majeurs d'infrastructure de navigation maritime et fluviale et dans l'orientation de ses travaux au bénéfice des pays émergents. 13 C. DUCRUET. - The Polarization of Global Container Flows by Inter- oceanic Canals. 27 P. DRANK.IER. - Connecting China Overseas through the Marine Arc tic: Le gal lmplications and Geopolitical Considerations for Arctic Shipping..................... 45 D. DE LAME. - Connected by Oceans, Parted by Land............ 61 S. A. RrcH. - "Shiver Me Timbers ! "No Cedar Ships in the Medieval Mediterranean? . 69 The Suez Canal in between the Gibraltar and Malacca Straits N. -

The Nostalgia Collection the French Connection Mail to and from China, Indochina and Japan

The Nostalgia Collection The French Connection Mail to and from China, Indochina and Japan Auction Sunday June 26, 2016 Lots 653 - 791 commencing at 5:30 pm at The Excelsior Hotel, Hong Kong Marina Room Level 2 281 Gloucester Road Causeway Bay Hong Kong Auction telephone : +852 2868 6046 Viewing at The Excelsior Hotel, Hong Kong Kellett Room Friday June 24 9 am to 6 pm Level 3 Saturday June 25 9 am to 6 pm 281 Gloucester Road Causeway Bay Hong Kong Front Cover Illustration Lot 677 Back Cover Illustration Lots 766, 784, 734, 673, 735, 785 & 690 Dr. Jeffrey S. Schneider Cecilia Vong Robert Schneider Daniel Wong Interasia Auctions Limited Suite A, 13/F, Shun Ho Tower, 24-30 Ice House Street, Central, Hong Kong Telephone: +852 2868 6046 Facsimile: +852 2868 6146 Email: [email protected] Website: www.interasia-auctions.com Table of Contents Early Mail, 1770-1860 653 - 663 Second Opium War French Expeditionary Forces, 1860-62 664 - 677 French Post Office in Shanghai 678 - 688 Accountancy Markings and Depreciated Currency 689 - 691 Mail from France to China, including Ligne M 692 - 700 Mail from China by Private Ship 701 Mail from Hong Kong and Treaty Ports by French Packet 702 - 710 Hong Kong Mail Cancelled on Board French Mail Boats 711 - 715 Mail from or to Other Countries Carried by French Packets 716 - 724 The Evans and Rainbow Correspondence 725 - 729 Indochina, 1864-68 730 - 733 French Post Offices in Shanghai/Chinese Customs and Imperial Post 734 - 741 French Post Offices in China (towns other than Shanghai) 742 - 749 French -

Introducing the Brand-New Queen Elizabeth Theodore W

OCTOBER, 2010 VOLUME XXVII, # 9 Friday October 29, 6:00 PM At the Community Church Assembly Room, 40 E. 35th Street, New York, NY: INTRODUCING THE BRAND-NEW QUEEN ELIZABETH THEODORE W. SCULL On 12TH October 2010, following a naming ceremony performed by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Cunard’s 92,400-ton QUEEN ELIZABETH set out on her maiden voyage from Southampton to Iberia, Madeira and the Canary Islands. Slightly larger in gross tonnage than QUEEN VICTORIA, she qualifies as the second largest Cunarder ever built, the third to carry the name Queen Elizabeth and the third QUEEN in the present fleet. The October program is under the direction of our Program Chairman Theodore W. Scull, who will present a first-hand look at the new ship, drawing on a personal inspection in Southampton and on input by other World Ship Society members based in England who will photograph the ship and her initial October sailings to and from her homeport. Join us as we celebrate Cunard Line’s expanding presence on the high seas and continuing tradition dating back 170 years. QUEEN ELIZABETH ON SEA TRIALS (Cunard Line) ADDRESS: NEXT MEETINGS: PO Box 384 Thursday, Nov. 18; Wednesday, Dec.15 – Holiday Party and New York, NY 10185-0384 John-Maxtone-Graham lecture on FRANCE / NORWAY Friday, January 28; Friday, February 25; Thursday, March 24; Friday, April 29; Friday, May 20; Friday, June 24 E-MAIL: WEB SITE: [email protected] www.worldshipny.com THE PORTHOLE, published by the Port of New York Branch, World Ship Society, welcomes original material for publication. -

Shipping Lines: History and Heritage

Association Shipping Lines: History and Heritage Contents President's message 4 French Lines: Heritage and Objectives 6 Collections 7 Films and photographs 11 Archives 12 Sound archives 14 A brief history... 16 The Messageries Maritimes Company 17 André Lebon 19 Champollion 20 The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique 21 Normandie 23 France 24 The Compagnie Générale Maritime 25 SNCM 26 Delmas 27 Chargeurs Réunis (United Shippers) 28 French Lines Services 30 Shop 31 Website and trademarks 31 Join us! 32 Acknowledgements 33 President's Message The French Lines Association was created in 1995 and is dedicated to the conservation and promotion of French shipping company heritage. The Association is a recognised public interest institution with locations in commercial ports that have marked the companies' history such as Le Havre, Marseille, Dunkirk, Bordeaux and Paris. In Le Havre, we have an area spanning almost 2,500 m dedicated to the historical preservation of the Compagnie Générale Maritime heritage, successor of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique and the Messageries Maritimes, as well as the Société Nationale Corse Méditerranée. Over the years, our work has been acknowledged by members of the Merchant Navy. Some have become partners of French Lines, such as Louis-Dreyfus, Marseille Fret, STIM d'Orbigny, La Méridionale de Navigation, la Compagnie Nationale de Navigation and Armateurs de France. French Lines also house a number of archives including archives for companies such as Delmas, Chargeurs Réunis and Le Borgne. Our objective is to raise awareness of the Merchant Navy's vital role in politics, technology, economics and society throughout history, as well as its inuence on the evolution of taste and art. -

Mooltan (1905)

Ship Fact Shee t MOOLTAN (1905) Base data at 8 October 1905. Last amended November 2008 * indicates entries changed during P&O Group service. Type Passenger liner P&O Group service 1905-1917 P&O Group status Owned by parent company Registered owners, The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation managers and operators Company Builders Caird & Co Ltd Yard Greenock Country UK Yard number 306 Registry Greenock, UK Official number 117397 Signal letters HDNQ Call sign Classification society Lloyd’s Register Gross tonnage 9,621 grt Net tonnage 4,828 nrt Deadweight* 6,058 tons Length 158.56m (520.4ft) Breadth 17.76m (58.3ft) Depth 7.53m (24.7ft) Draught* 8.341m (27ft 4½in) Engines Quadruple-expansion steam engines Engine builders Caird & Co Ltd Works Greenock Country UK Power 13,000 ihp Propulsion Twin screw Speed 18 knots Passenger capacity 348 first class, 166 second class Cargo capacity 5,459 cubic metres (192,800 cubic feet) including 1,967 cubic metres (68,478 cubic feet) refrigerated Crew [1914] 328 (134 European, 194 Asian). Deck 24 European, 51 Asian; engineroom 16 European, 101 Asians; purser’s department 107 European, 42 Asian Employment UK/Australia or UK/India mail services 0209 1905/1008 MOOLTAN (1905) Career 03.08.1905: Launched. 04.10.1905: Registered. 08.10.1905: Left her builders as Mooltan for The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company at a cost of £314,982. The name is a variation of Multan, a town now in Pakistan, previously used by P&O in 1861. 28.10.1905: Exhibited for charity at Tilbury for two days - proceeds to the Seamen’s Hospital, Greenwich.