Communiqué / Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

The Gold Medal for Italian Architecture 6Th Edition La Triennale Di Milano January - October 2018

The Gold Medal for Italian Architecture 6th Edition La Triennale di Milano January - October 2018 General information La Triennale di Milano, in collaboration with MiBACT, the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Cultural Activities and Tourism, announces the sixth edition of the Gold Medal Prize for Italian Architecture. The event is held every three years to promote, and to reflect on, the latest, most interesting works built in the country, and on those who have made these works possible. The Gold Medal for Italian Architecture aims to promote contemporary architecture as a means for improving the quality of the environment and civil life, while also looking at architecture as the outcome of the dynamic interaction between architects, clients and companies. The Gold Medal for Italian Architecture offers an active reflection on the role of architects and on their works, with the aim of introducing the public in Italy and abroad to a new heritage of buildings and ideas. It also provides a periodical overview of the state of Italian architectural production, illustrating its problems, trends and new exponents. Procedure The Prize consists of the following categories: – Gold Medal for Best Work, for the quality of the design, the environmental intelligence and setting, and the construction and capacity for technological innovation. All the works selected by the jury for the various sections indicated below compete for the Gold Medal. – Special First Work Award for the best first work by an architect under the age of 40, aims to give due prominence to a new generation working in Italy and abroad. – Special Award for Clients. -

Mobile Structures of Santiago Calatrava: Other Ways of Producing Architecture

MOBILE STRUCTURES OF SANTIAGO CALATRAVA: OTHER WAYS OF PRODUCING ARCHITECTURE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ARZU EMEL YILDIZ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE JANUARY 2007 Approval of the Graduate School of Applied and Natural Sciences Prof.Dr. Canan Özgen Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Architecture. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selahattin Önür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Architecture. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşen Savaş Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Jale Nejdet Erzen (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşen Savaş (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali İhsan Ünay (METU, ARCH) Assist. Prof. Dr. Berin Gür (METU, ARCH) Inst. Dr. Türel Saranlı (BASKENT UNI., ARCH) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Arzu Emel Yıldız Signature: iii ABSTRACT MOBILE STRUCTURES OF SANTIAGO CALATRAVA: OTHER WAYS OF PRODUCING ARCHITECTURE Yıldız, Arzu Emel M.Arch., Department of Architecture Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşen Savaş January 2007, 123 pages This thesis conceptualizes the term “movement” as a design medium for producing architecture. -

Artbookdap Catalog-1.Pdf

Sonia Delaunay, “Five Designs for Children’s Clothing,” 1920. From Sonia Delaunay: Art, Design, Fashion, published by Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza. See page 18. FEATURED RELEASES 2 Journals 90 Limited Editions 92 Lower-Priced Books 94 Backlist Highlights from Lars Müller 95 Backlist Highlights from Skira 96 Backlist Highlights from Heni & Inventory Press 97 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans ART DIRECTOR SPRING HIGHLIGHTS 98 Stacy Wakefield IMAGE PRODUCTION Art 100 Hayden Anderson, Isabelle Baldwin Photography 130 COPY WRITING Architecture & Design 148 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans Art History 166 PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Writings 169 FRONT COVER IMAGE SPECIALTY BOOKS 176 Burt Glinn, “Jay DeFeo in Her Studio,” 1960. From The Beat Scene, published by Reel Art Art 178 Press. See page 41. Group Exhibitions 194 BACK COVER IMAGE Photography 198 Anna Zemánková, untitled pastel, oil and ink drawing, early 1960s. From Anna Zemánková, Backlist Highlights 206 published by Kant. See page 109. Index 215 Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts Edited by Kathy Halbreich, Isabel Friedli, Heidi Naef, Magnus Schaefer, Taylor Walsh. Text by Thomas Beard, Briony Fer, Nicolás Guagnini, Kathy Halbreich, Rachel Harrison, Ute Holl, Suzanne Hudson, Julia Keller, Liz Kotz, Ralph Lemon, Glenn Ligon, Catherine Lord, Roxana Marcoci, Magnus Schaefer, Felicity Scott, Martina Venanzoni, Taylor Walsh, Jeffrey Weiss. At 76 years old, Bruce Nauman is widely ac- knowledged as a central figure in contemporary art whose stringent questioning of values such as good and bad remains urgent today. Throughout his 50-year career, he has explored how mutable experiences of time, space, sound, movement and language provide an insecure foundation for our understanding of our place in the world. -

The Rise of the Curator and Architecture on Display

THE RISE OF THE CURATOR AND ARCHITECTURE ON DISPLAY Eszter Steierhoffer A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JanuAry 2016 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding thAt it is copyright material, And that no quotation from the thesis mAy be published without proper acknowledgment. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis constitutes a new Approach to contemporary exhibition studies, a field of research that has until now dedicated little attention to connections between exhibitions of contemporary art and those of architecture. The late 1970s saw a 'historical turn' in the architectural discourse, which alluded to the rediscovery of history, After its abandonment by all the Modern masters, and developed in close alignment with architecture’s project of autonomy. This thesis proposes a reading of this period in relation to the formative moment for contemporary curatorial practices that brought art and architecture together in unprecedented wAys. It takes its starting point from the coexisting and often contradictory spatial representations of art and architecture that occur in exhibitions, which constitute the inherently paradoxical foundations – and legacy – of today’s curatorial discourse. The timeframe of the late 1970s, which is this study’s primary focus, marks the beginning of the institutionalisation of the architecture exhibition: The opening of the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1977), the founding of ICAM in Helsinki (1979), and the first official International Architecture BiennAle in Venice (1980), all of which promoted architecture within the museum. -

Peter Sealy:1 Why Does the Canadian Centre for Architecture Do Books?

Peter Sealy:1 Why does the Canadian Centre for Architecture do books? Phyllis Lambert:2 Why the CCA does books is a little obvious. We do books because they are long-term references. An exhibition is a way of communicating a theme, but it’s a temporary reference. We don’t do cata- logues. A catalogue has every object in it. We do books referencing the problematic that we’re dealing with. Mirko Zardini:3 The way the CCA does books is being shaped by new tools of communication, such as the web, as well as by the changing cultural landscape of which we are a part. For example, the number of architectural publications — especially monographs — has increased dramatically in the last twenty or thirty years. The paradox is that during this period, we have seen a decline in the status of the traditional architecture magazine. PL: In the beginning, we MZ: Now each time we prepare published ourselves, and MIT a book, we speak with two or Press handled most of the dis- three publishers; we discuss tribution. It wasn’t until 2001 their ideas and their approach that we decided we were a to the project and then make much too small place to have our choice. It’s crucial to find somebody in-house who’s in a publisher who is interested charge of putting the book in the project. Of course there together, somebody else in- are many economic consider- house who was editor . From ations, but above all we must Herzog & de Meuron onwards find somebody who is willing we have always worked with to work with us. -

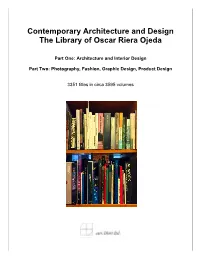

Contemporary Architecture and Design the Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda

Contemporary Architecture and Design The Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda Part One: Architecture and Interior Design Part Two: Photography, Fashion, Graphic Design, Product Design 3351 titles in circa 3595 volumes Contemporary Architecture and Design The Library of Oscar Riera Ojeda Part One: Architecture and Interior Design Part Two: Photography, Fashion, Graphic Design, Product Design 3351 titles in circa 3595 volumes The Oscar Riera Ojeda Library comprised of some 3500 volumes is focused on modern and contemporary architecture and design, with an emphasis on sophisticated recent publications. Mr. Riera Ojeda is himself the principal of Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, and its imprint oropublishers, which have produced some of the best contemporary architecture and design books of the past decade. In addition to his role as publisher, Mr. Riera Ojeda has also contributed substantively to a number of these as editor and designer. Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers works with an international team of affiliates, publishing monographs on architects, architectural practice and theory, architectural competitions, building types and individual buildings, cities, landscape and the environment, architectural photo- graphy, and design and communications. All of this is reflected in the Riera Ojeda Library, which offers an international conspectus on the most significant activity in these fields today, as well as a grounding in earlier twentieth-century architectural history, from Lutyens and Wright through Mies and Barragan. Its coverage of the major architects -

Press Release

Centre Canadien d’Architecture 1920, rue Baile Canadian Centre for Architecture Montréal, Québec Canada H3H 2S6 t 514 939 7000 f 514 939 7020 www.cca.qc.ca Communiqué/Press Release For immediate distribution ROOMS YOU MAY HAVE MISSED : UMBERTO RIVA , BIJOY JAIN THIS FIRST NORTH AMERICAN EXHIBITION OF THE ITALIAN AND INDIAN ARCHITECTS EXPLORES TWO DISTINCT APPROACHES TO CONCEIVING AND BUILDING RESIDENTIAL SPACES . Ahmedabad House, view of the courtyard with marble lined pool Casa Insinga, view of shelf in the kitchen, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, 2014. Studio Mumbai Architects Milan, Lombardy, Italy, 1990. Umberto Riva Architetto Photograph by Srijaya Anumolu. © Studio Mumbai Photograph by Giovanni Chiaramonte. © Giovanni Chiaramonte. Montréal, 23 October 2014 — The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) presents the work of architects Umberto Riva (1928–) and Bijoy Jain (1965–) in its forthcoming exhibition Rooms You May Have Missed . Curated by CCA Director Mirko Zardini, the exhibition explores how the room as an elemental unit of architecture has been reevaluated by two architects from different generations and cultures—late-twentieth-century Italy and present-day India. The exhibition is on view in the CCA’s Main Galleries from 4 November 2014 until 19 April 2015 . Rooms You May Have Missed interrupts the CCA’s long-term investigation of the role of digital tools in architecture (manifested in the ongoing exhibition series Archaeology of the Digital ) to examine alternative architectural strategies and specific, regionally influenced production methods. The drawings, models, and materials included in the exhibition illustrate the respective forms of authorship that emerge from the processes Riva and Jain put into place.