The Rise of the Curator and Architecture on Display

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1St Contact Address

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1st Contact address William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor Assistant Chair Studio Division University of Texas at Austin College of Fine Arts, Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Station D1300 Austin, TX 78712-1421 USA [email protected] 2nd Contact address 4707 Shoalwood Ave Austin, TX 78756 USA [email protected] www.hubbardbirchler.net mobile +512 925 2308 Contents 2 Education and Teaching 3–5 Selected Public Lectures and Visiting Artist Appointments 5–6 Selected Academic and Public Service 6–8 Selected Solo Exhibitions 8–14 Selected Group Exhibitions 14–20 Bibliography - Selected Exhibition Catalogues and Books 20–24 Bibliography - Selected Articles 24–28 Selected Awards, Commissions and Fellowships 28 Gallery Representation 28–29 Selected Public Collections Teresa Hubbard, Curriculum Vitae - 1 / 29 Teresa Hubbard American, Irish and Swiss Citizen, born 1965 in Dublin, Ireland Education 1990–1992 M.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Canada 1988 Yale University School of Art, MFA Program, New Haven, Connecticut, USA 1987 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, USA 1985–1988 University of Texas at Austin, BFA Degree, Austin, Texas, USA 1983–1985 Louisiana State University, Liberal Arts, Baton Rouge, USA Teaching 2015–present Faculty Member, European Graduate School, (EGS), Saas-Fee, Switzerland 2014–present William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor, Department of Art and Art History, College of Fine Arts, University of Texas -

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

Aarch Matters

AARCH MATTERS COVID-19 UPDATE: The effects of the novel coronavirus have affected us all, especially impacting the ability of nonprofits and cultural organizations like AARCH to deliver its usual slate of rich slate of programming and events. It is at this time we must remain resilient. Although this year’s events may be postponed and/or cancelled, we are remaining optimistic that we will bring this content to YOU in some way going forward. Please READ ON, and carry our message of resilience, hope, and love, even if we may not be able to share in our adventures together in person this year. Be safe, and remember that the sun will continue to rise each day. A PATCHWORK of RESILIENCE CHRONICLING SUSTAINABILITY, ENERGY, WORK, AND STORIES EMBODIED IN OUR REGION Resilience – “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties” – is a trait escaping enslavement, early 20th century Chinese freedom seekers jailed that allows plants, animals, and humans to adapt and even thrive in as they came south from Canada, and the thousands of immigrants now adversity. And it is a characteristic that we admire and learn from, as it’s flooding across a tiny, illegal crossing to find security and hope in Canada. what makes or should make each generation better than the last. In this Or there is the story of how Inez Milholland and other North Country era of looming climate change and now with the scourge of the women fought for their right to vote and be heard, and the extraordinary coronavirus sweeping across the globe, we’ve realized that we need to story of Isaac Johnson, a formerly enslaved African American stone create a world that is safer, sustainable, more equitable, and resilient and mason who settled in the St. -

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Santa's Coming

PALIHI’S SUPER BOWL ‘TROPHY’ Vol. 2, No. 3 • December 2, 2015 Uniting the Community with News, Features and Commentary Circulation: 15,000 • $1.00 See Page 25 Turkey Trotting Time ‘Citizen’ Kilbride To Be Honored December 10 By LAURIE ROSENTHAL Staff Writer itizen of the Year Sharon Kilbride lives in the Santa Monica Canyon Chome that she grew up in, on prop- erty that has been in the family since 1839. The original land grant—Rancho Boca de Santa Monica—once encompassed 6,656 acres, and stretched from where Topanga Canyon meets the ocean to what is now San Vicente around 20th Street. Six generations of the Marquez family have lived in Santa Monica Canyon, which was a working rancho. Kilbride’s great-grandfather, Miguel Mar - quez, built the original house, the same one where Kilbride’s mother, Rosemary Close to 1,400 runners spent early Thanksgiving morning running in the third annual Banc of California Turkey Trot, be- Romero Marquez, grew up. According to ginning and ending at Palisades High. (See story, page 27). Photo: Shelby Pascoe Kilbride’s brother, Fred, “The property has never been bought or sold.” Rosemary attended Canyon School, as Ho!Ho!Ho! Santa’s Coming (Continued on Page 4) By SUE PASCOE DRB May Discuss Editor anta and Mrs. Claus are coming to Pacific Palisades for Caruso’s Plans the Chamber’s traditional Ho!Ho!Ho! festivities on Friday, The Design Review Board will hold a December 4, from 5 to 8 p.m. regularly scheduled meeting at 7 p.m. on S Wednesday, December 9, at the Palisades After the reindeer land, Station 69 firefighters will load the Clauses onto a firetruck and deliver them to Swarthmore. -

Read This Issue

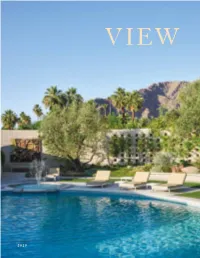

VIEW 2019 VIEW from the Director’s Office Dear Friends of LALH, This year’s VIEW reflects our recent sharpening focus on California, from the Bay Area to San Diego. We open with an article by JC Miller about Robert Royston’s final project, the Harris garden in Palm Springs, which he worked on personally and continues to develop with the owners. A forthcoming LALH book on Royston by Miller and Reuben M. Rainey, the fourth volume in our Masters of Modern Landscape Design series, will be released early next year at Modernism Week in Palm Springs. Both article and book feature new photographs by the stellar landscape photographer Millicent Harvey. Next up, Kenneth I. Helphand explores Lawrence Halprin’s extraordinary drawings and their role in his de- sign process. “I find that I think most effectively graphically,” Halprin explained, and Helphand’s look at Halprin’s prolific notebook sketches and drawings vividly illuminates the creative symbiosis that led to the built works. The California theme continues with an introduction to Paul Thiene, the German-born landscape architect who super- vised the landscape development of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and went on to establish a thriving practice in the Southland. Next, the renowned architect Marc Appleton writes about his own Santa Barbara garden, Villa Corbeau, inspired—as were so many of Thiene’s designs—by Italy. The influence of Italy was also major in the career of Lockwood de Forest Jr. Here, Ann de Forest remembers her grandparents and their Santa Barbara home as the family archives, recently donated by LALH, are moved to the Architecture & Design Collections at UC Santa Barbara. -

Apexart 291 Church Street, New York, Ny 10013 T

The Incidental Person The British artist John Latham (1921–2006) coined the elements of space and matter (this would be the space- January 6 to February 20, 2010 expression the “Incidental Person” (IP) to qualify an based or (S) framework), but by time, and by the basic individual who engages in non-art contexts – industry, temporal unit Latham called “the least event”. Curated by Antony Hudek politics, education – while avoiding the “for/against”, The implications of the shift from space-and- “you vs. me” disposition typically adopted to resolve matter to time-and-event are far-reaching. Gone, for Contributors’ names appear in red in the text. Darker differences. The IP, Latham argued, “may be able, example, is the division between subject and object. red indicates faculty and students from Portland State University MFA Art and Social Practice Concentration. given access to matters of public interest ranging from Formerly perceived as ontologically different, in the national economic, through the environmental the (T) framework subject and object co-exist in Special thanks to Ron Bernstein, Sara De Bondt, and departments of the administration to the ethical varying simultaneous temporal frequencies or, to Romilly Eveleigh, Anna Gritz, Joe at The Onion, Cybele Maylone, Barbara Steveni, Athanasios Velios in social orRon Bernsteinientation, to ‘put forward use Latham’s terminology, in various “time-bases”. 1 and Ewelina Warner. answers to questions we have not yet asked’.” ObjJoachim Pfeuferects themselves no longer occupy Diagrammatically, the IP transforms the linear, two- stable positions in the taxonomic grids belonging to Cover image: Invitation to APG seminar, Royal College dimensional plane of conflict into a three-dimensional, distinct disciplines. -

Biographies Randy Chan Randy Chan Is an Award-Winning Architect

YEO WORKSHOP Gillman Barracks SG +65 67345168 [email protected] www.yeoworkshop.com 1 Lock Road, S (108932) Biographies Randy Chan Randy Chan is an award-winning architect and artist. Chan’s architectural and design experience crosses multiple fields and scales, all guided by the simple philosophy that architecture and aesthetics are part of the same impulse. Chan is the principal of Zarch Collaboratives - one of Singapore’s leading architectural studios established in 1999. The objective of the studio is to practice and fulfil architectural projects but also cross disciplines and approach the means of spatial design. They have worked on a series of exhibition spaces, stage set designs, art installations, world expositions and catered for private and public housing plans. Additionally, Chan is the creative director of Singapore: Inside Out, an international platform featuring a collection of multi-disciplinary experiences created by practicing artists. It is a platform with a global intention. It accommodates and presents the creative talents of Beijing, London, New York and Singapore. Artistically it combines the varying disciplines of architecture, design, fashion, film, food, music, performance and the visual arts. Hubertus von Amelunxen Professor Dr. Hubertus von Amelunxen was born in Hindelang, Germany in 1958. He lives in Berlin and Switzerland. After studies in French and German Literature and in Art History at the Philipps- Universität, Marburg and the École Normale Supérieure de Paris, he wrote his Ph.D. on Allegory and Photography: Inquiries into 19th Century French Literature. He was professor of Cultural Studies and the Founding Director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Research at the Muthesius Academy of Architecture, Design and Fine Arts in Kiel between 1995 and 2000. -

The Exhibition: Histories, Practices, Policies

The Exhibition: Histories, Practices, Policies N. 1 4 2019 issn 1646-1762 issn faculdade de ciências sociais e humanas – nova Revista de História da Arte N. 14 2019 The Exhibition: Histories, Practices and Politics BOARD (NOVA/FCSH) Margarida Medeiros (ICNOVA/NOVA/FCSH) Joana Cunha Leal Nuno Faleiro Rodrigues (CEAA, ESAP) Alexandra Curvelo Pedro Flor (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) Margarida Brito Alves Pedro Lapa (FLUL) Pedro Flor Raquel Henriques da Silva (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) SCIENTIFIC COORDINATION – RHA 14 Sandra Leandro (IHA/NOVA/FCSH; UE) Joana Baião (IHA/NOVA/FCSH; CIMO/IPB) Sandra Vieira Jürgens (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) Leonor de Oliveira (IHA/NOVA/FCSH; Courtauld Institute Sarah Catenacci (Independent art historian, Rome) of Art) Sofia Ponte (FBAUP) Susana S. Martins (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) Susana Lourenço Marques (FBAUP; IHA/NOVA/FCSH) Tamara Díaz Bringas (Independent researcher and curator, Cuba) EDITORIAL COORDINATION Victor Flores (CICANT/ULHT) Ana Paula Louro Joana Baião ENGLISH PROOFREADING Leonor de Oliveira KennisTranslations Lda. Susana S. Martins Thomas Williams REVIEWERS (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) PUBLISHER Alda Costa (Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo) Instituto de História da Arte (NOVA/FCSH) Ana Balona de Oliveira (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) DESIGN Ana Carvalho (CIDEHUS/UE) José Domingues Carlos Garrido Castellano (University College Cork) ISSN Giulia Lamoni (IHA/NOVA/FCSH) 1646-1762 Gregory Scholette (Queens College/City University of New York) Helena Barranha (IHA/NOVA/FCSH; IST/UL) © copyright 2019 Hélia Marçal (Tate Modern, London) The authors and the Instituto de História da Arte (NOVA/ João Carvalho Dias (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation) FCSH) José Alberto Gomes Machado (CHAIA/UE) © cover photo Katarzyna Ruchel-Stockmans (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) View of Graciela Carnevale’s 1968 action Encierro Laura Castro (School of Arts/UCP) (Confinement), Rosario, Argentina. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The State of Architecture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6s86b2s6 Author Fabbrini, Sebastiano Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The State of Architecture A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Sebastiano Fabbrini 2018 © Copyright by Sebastiano Fabbrini 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The State of Architecture by Sebastiano Fabbrini Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Although architecture was historically considered the most public of the arts and the interdependence between building and the public realm was a key feature of the post-war discourse, the process of postmodernization undermined the traditional structures of power through which architecture operated. At the center of this shakeup was the modern structure par excellence : the State. This dissertation analyzes the dissolution of the bond between architecture and the State through a double lens. First, this study is framed by the workings of an architect, Aldo Rossi, whose practice mirrored this transformation in a unique way, going from Mussolini’s Italy to Reagan’s America, from the Communist Party to Disneyland. The second lens is provided by a set of technological apparatuses ii that, in this pre-digital world, impacted the reach of the State and the boundaries of architecture. Drawing on the multifaceted root of the term “State,” this dissertation sets out to explore a series of case studies that addressed the need to re-state architecture – both in the sense of relocating architecture within new landscapes of power and in the sense of finding ways to keep reproducing it in those uncharted territories. -

On Vilém Flusser's Towards a Philosophy Of

FLUSSER STUDIES 10 Photography and Beyond: On Vilém Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography The following short pictorial and textual contributions by Mark Amerika, Sean Cubitt, John Goto, Andreas Müller-Pohle, Michael Najjar, Simone Osthoff, Nancy Roth, Bernd-Alexander Stiegler, Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Siegfried Zielinski explore the practical and theoretical relevance and actuality of Vilém Flusser‘s Towards a Philosophy of Photography, first published as Für eine Philosophie der Fotografie in 1983. It has been translated into more than 14 different languages. These observations are based on the following questions: What is the theoretical and practical relevance of Flusser‘s Towards a Philosophy of Photography, written more than 25 years ago and translated into many languages? What was the impact of Flusser‘s conception of photography on the artistic practice of photography and image-creation internationally? Beyond Flusser: What is the status of photography and images within the present context of digital cameras and 3-D film? What new theoretical parameters and models enliven the scholarly debates on and artistic engagements with photography and images? How do theories of the (technical) image promote interdisciplinary scholarship? Rainer Guldin and Anke Finger Lugano / Storrs, November 2010 1 FLUSSER STUDIES 10 Mark Amerika, Applied Flusser [email protected] Flusser, in Toward A Philosophy of Photography writes: ―The task of the philosophy of photography is to question photographers about freedom, to probe their practice in pursuit of freedom.‖ Here, the photographer is not just someone who uses a camera to take pictures, but is a kind of hybrid who is part science fiction philosopher and part data gleaner. -

John Latham's Cosmos and Midcentury Representation

John Latham's cosmos and mid-century representation Article (Accepted Version) Rycroft, Simon (2016) John Latham’s cosmos and mid-century representation. Visual Culture in Britain, 17 (1). pp. 99-119. ISSN 1471-4787 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/60729/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Visual Culture in Britain For Peer Review Only John Latham’s Cosmos and Mid -Century Representation Journal: Visual Culture in Britain Manuscript ID RVCB-2015-0004.R1 Manuscript Type: Original Paper Keywords: John Latham, Mid-century, Skoob, Conceptual art, Cosmology URL: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/rvcb Page 1 of 39 Visual Culture in Britain 1 2 3 John Latham’s Cosmos and Mid-Century Representation 4 5 6 7 8 The conceptual artist John Latham (1921 – 2006) is sometimes cast as disconnected to the currents of British 9 10 visual culture.