Revisiting the REDD+ Experience in Indonesia Lessons from National, Subnational and Local Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 565 Proceedings of the International Conference on Education Universitas PGRI Palembang (INCoEPP 2021) Free School Leadership Meilia Rosani1, Misdalina1*), Tri Widayatsih1 1Universitas PGRI Palembang, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The introduction of free schools needs to be dealt with seriously by the leader. Seriousness is shown by his ability to lead. Leadership is required so that the introduction of free schools can be guided and targets can be accomplished quickly and efficiently. The purpose of this study was to decide how free school leadership is in the Musi Banyuasin Regency (MUBA). This research uses a qualitative approach to the case study process. The data collection technique was conducted by interviewing, analyzing and recording the validity of the data used in the triangulation process. The results show that free school leadership in the MUBA district is focused on coordination, collaboration, productivity in the division of roles, the arrangement of the activities of the management team members in an integrated and sustainable manner between the district management team and the school. Keywords: Leadership, Cohesion, Performance, Sustainability 1. INTRODUCTION Regional Governments, that education and the enhancement of the quality of human resources in the The Free School that is introduced in MUBA regions are also the responsibility of the Regional Regency is a program of the MUBA Regency Government. In addition to this clause, the leaders of the Government that has been implemented since 2003. MUBA District Government, along with stakeholders Until now, the software has been running well. -

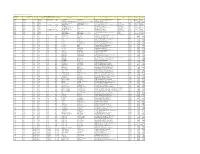

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

18Th Asian Games Success Story

18th Asian Games Runs Faultless Secure Network The 2018 Asian Games, held in Jakarta and Palembang, enjoy secure and faultless network performance. Customer: The 18th Asian Games Industry: Sports/Entertainment Location: Jakarta, Indonesia and Palembang, South Sumatera The Challenge – Security On A Large Scale The 18th Asian Games, also known as Jakarta–Palembang 2018, was a multi-sport event held from 18 August to 2 September 2018 in Indonesia. The Asian Games are one of the world’s largest sporting events, held every four years since 1954. More than 16,000 athletes from 45 Asian countries participated in the 2018 Games. For the first time, the Asian Games were co-hosted in two cities; the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, and Palembang, the capital of the South Sumatera province. Preparation for the Games involved building new venues and renovating existing venues across four provinces in Indonesia: Jakarta, South Sumatra, Banten, and West Java. A total of 80 venues were involved, with the main stadium, Gelora Bung Karno, located in Jakarta. The Asian Games are a large-scale international event. The 2018 Games had to cater to many thousands of people—including athletes, spectators, organizers and supporters, from 45 different countries. An incredibly robust video surveillance system, along with many other security measures, was essential for both smooth operation and for the safety and security of everyone present at the Games. The Asia Olympic Committee worked with PT. NEC Indonesia (NEC Indonesia), the ICT security system partner for the 2018 Games. Their goal: to create a smart, safe and highly-efficient environment, by deploying an innovative network infrastructure alongside advanced video surveillance systems. -

How Strong Is the Integrity Disclosure in Indonesian Province Website?

Journal of Contemporary Accounting, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2021, 33-44 Journal of Contemporary Accounting Volume 3 | Issue 1 How strong is the integrity disclosure in Indonesian Province website? Maria Hellenikapoulos Department of Accounting, Satya Wacana Christian University, Salatiga, Indonesia [email protected] Intiyas Utami Department of Accounting, Satya Wacana Christian University, Salatiga, Indonesia [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://journal.uii.ac.id/jca Copyright ©2021 Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Authors. Maria Hellenikapoulos & Intiyas Utami. (2021). How strong is the integrity disclosure in Indonesian Province website? Journal of Contemporary Accounting, 3(1), 33-44 doi:10.20885/jca.vol3.iss1.art4 Journal of Contemporary Accounting, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2021, 33-44 How strong is the integrity disclosure in Indonesian Province website? Maria Hellenikapoulos1*, Intiyas Utami2 1,2Department of Accounting, Satya Wacana Christian University, Salatiga, Indonesia Abstract The high level and trend of corruption in Indonesia Province could hinder the goal of Sustainable Development Goals point 16. This study aims to identify disclosures of integrity through websites and classify the Indonesia Provinces into 3 categories, namely high, medium, and low based on the integrity disclosure index using institutional theory. The data is based on content analysis to analyze practices through disclosure of integrity on 34 Indonesian Province websites using the Integrity Framework Disclosure Index instrument. The findings indicate that Indonesia has disclosed 775 items (48%). The items of vision, mission, and integrity report are the biggest disclosed items among other items that show Indonesia’s effort to create a “good image” in the public eyes. -

Food Security and Environmental Sustainability on the South Sumatra Wetlands, Indonesia Syuhada, A.*1, M

Sys Rev Pharm 2020; 11(3): 457 464 A multifaceted review journal in the field of pharmacy E-ISSN 0976-2779 P-ISSN 0975-8453 Food Security and Environmental Sustainability on the South Sumatra Wetlands, Indonesia Syuhada, A.*1, M. Edi Armanto2, A. Siswanto3, M. Yazid4, Elisa Wildayana5 1* Environmental Study Program, Postgraduate Program, Sriwijaya University, Jln Raya Palembang-Prabumulih KM 32, Indralaya Campus, South Sumatra, Indonesia 2.4.5 Faculty of Agriculture, Sriwijaya University, Jln Raya Palembang-Prabumulih KM 32, Indralaya Campus, South Sumatra, Indonesia 3 Faculty of Engineering, Sriwijaya University, Jln Raya Palembang-Prabumulih KM 32, Indralaya Campus, South Sumatra, Indonesia. Article History: Submitted: 25.12.2019 Revised: 22.02.2020 Accepted: 10.03.2020 ABSTRACT The research aimed to analyze food security and environmental continuous rice-based; extensive perennial-based crops; and vegetable- sustainability in the South Sumatra wetlands. This research conducted on based crops. The main typology was dominated by continuous rice-based the wetlands of Banyuasin Regency, By Using the Survey method system taking around 197.961 ha or 58.50% and the lowest level was interview with respondents, guided by a questionnaire through the Focus shown by vegetable-based crops around 20.998 ha or 6.20%. Group Discussion (FGD). All data collected, by analyzed with SPSS Keywords: Food security, environmental sustainability, wetlands program. The results showed that plants planted in wetlands vary widely, Correspondance: such as rice, corn, soy, sweet potatoes, nuts, and cassava. The diversity of Syuhada, A commodities is cultivated on high enough wetlands; they seek food Environmental Study Program, Postgraduate Program, farming in order to meet their own subsistence with little agricultural input, Sriwijaya University, making it relatively difficult for crops to be able to produce optimally. -

INVESTING in NATURE for DEVELOPMENT: Do Nature-Based Interventions Deliver Local Development Outcomes? Photo Credits

INVESTING IN NATURE FOR DEVELOPMENT: do nature-based interventions deliver local development outcomes? Photo credits: Cover — JB Russell/Panos Pictures Fishermen cast their nets at sunrise in mangrove wetlands, Guinea Bissau. Traditional livelihoods in this region are being negatively impacted by ecosystem destruction from climate change and human activity. Inside pages: Page 8 — Diana Robinson via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 10 — Tomas Munita, CIFOR, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 12 — Rifky, CIFOR, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 16 — Devi Puspita Amartha Yahya via Unsplash Page 18 — Ajay Rastogi Page 19 — Axel Fassio, CIFOR, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 24 — Seyiram Kweku via Unsplash Page 29 — Ree Dexter via Flickr, CC BY 2.0 Page 31 — Hampus Eriksson, WorldFish, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 35 — Mike Lusmore/Duckrabbit, WorldFish, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 36 — psyren via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 Page 50 — Carsten ten Brink via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 51 — David Mills, WorldFish, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 52 — Nazmulhuqrussell via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 Page 55 — Dante Aguiar via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 Page 57 — Aulia Erlangga, CIFOR, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Page 58 — Anna Fawcus, WorldFish, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 INVESTING IN NATURE FOR DEVELOPMENT: do nature-based interventions deliver local development outcomes? This report was compiled in collaboration with the Nature-Based Solutions Initiative (NbSI) at the University of Oxford. -

Construction Raw Materials in India and Indonesia Market Study and Potential Analysis | Final Report May 2021 Imprint

Construction Raw Materials in India and Indonesia Market Study and Potential Analysis | Final Report May 2021 Imprint PUBLISHED BY Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR) Stilleweg 2 30655 Hannover (Germany) Copyright © 2021 by Levin Sources and the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ABOUT THIS REPORT This report presents the final results of a study on construction raw material value chains in two metropolitan areas in India and Indonesia. This study is a product of BGR’s sector project “Extractives and Development”, which is implemented on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The set up and the implementation of the study have been coordinated and accompanied by Hannah Maul. For more information please visit: www.bmz.de/rue/en AUTHORS This report was written by Victoria Gronwald, Nicolas Eslava, Olivia Lyster, Nayan Mitra and Vovia Witni, with research contributions from teams in Indonesia and India. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared from sources and data Levin Sources believes to be reliable at the time of writing, but Levin Sources makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. The report is provided for in- formational purposes and is not to be construed as providing endorsements, representations or warranties of any kind whatsoever. The authors accept no liability for any consequences whatsoever of pursuing any of the recommendations provided in this report, either singularly or altogether. -

&Green Jurisdictional Eligibility Criteria Assessment for the Republic of Indonesia

&GREEN JURISDICTIONAL ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA ASSESSMENT FOR THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA March 2020 Prepared for: &GREEN FUND PRINS BERNHARDPLEIN 200, 1097JB AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS PT Hatfield Indonesia Plaza Harmoni Unit B5-B7 Jl. Siliwangi No.46 Bogor 16131 Indonesia &GREEN JURISDICTIONAL ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA ASSESSMENT FOR THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA Prepared for: &GREEN FUND PRINS BERNHARDPLEIN 200 1097JB AMSTERDAM NETHERLANDS Prepared by: PT HATFIELD INDONESIA PLAZA HARMONI UNITS B5-B7 JL. SILIWANGI NO.46 BOGOR 16131 INDONESIA MARCH 2020 AGRN10116-BG VERSION 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................II LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................II LIST OF APPENDICES ....................................................................................II LIST OF ACRONYMS ......................................................................................III DISTRIBUTION LIST ..................................................................................... VII AMENDMENT RECORD ............................................................................... VII 1.0 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 HIGH LEVEL OF SUMMARY .................................................................1 JURISDICTIONAL SCOPE .....................................................................4 3.1 BACKGROUND: KEY ECONOMIC DATA AND MAPS ............................... -

Linking Food, Nutrition and the Environment in Indonesia a Perspective on Sustainable Food Systems

June 2021 DOI: 10.17528/cifor/008070 Linking food, nutrition and the environment in Indonesia A perspective on sustainable food systems Mulia Nurhasan1,2, Yusuf Bahtimi Samsudin1, John F McCarthy3, Lucentezza Napitupulu4, Rosita Dewi5, Dian N Hadihardjono6, Aser Rouw7, Kuntum Melati8, William Bellotti9, Rodri Tanoto10, Stuart J Campbell11, Desy Leo Ariesta1, M Hariyadi Setiawan12, Ali Khomsan13 and Amy Ickowitz1 Highlights • This brief reviews the interlinkages between food, nutrition and the environment in Indonesia, and the role of national food policies in addressing the challenges in these sectors. • While Indonesia is a mega-biodiverse country, nationally supported agricultural production programs tend to focus on a few high-value commodities, contributing to low dietary diversity. • Lessons from past food estate programs suggest that food system interventions that focus heavily on increasing monocropping, especially rice production, overlook the capacity of local people to develop their own food systems, while failing to provide healthy diets, and damaging the environment. • To move towards sustainable food systems, we argue that policies need to: focus on delivering healthy and diverse diets; support local food production practices that are environmentally sustainable; embrace local cultures and values; re-evaluate centralized and top-down policies; and avoid overly focusing on production of rice. • Policies that decentralize and localize food production can enhance resilience and the sustainability of food systems. 1 Center for -

2020 Asia-Pacific Statistics Week Leaving No One and Nowhere Behind

Virtual Event 15-18 June 2020 2020 Asia-Pacific Statistics Week Leaving no one and nowhere behind The Use of Mobile Positioning data to Measure Visitors of a Multisport Events: A Case study of ASIAN Games 2018 in Indonesia Action Area C. Methodological approaches to integrated analysis (SC1) Use of sound methodologies Authors: Amalia A. Widyasanti, Alfatihah Reno, Siim Esko, Margus Tiru, Titi Kanti Lestari Ministry of Planning, BPS-Statistics Indonesia, Positium LBS Present by: Amalia A. Widyasanti/Titi Kanti Lestari #apstatsweek2020 #apstatsweek2020 Event Analysis ASIAN GAMES Virtual Event 15-18 June 2020 2020 Asia-Pacific Statistics Week Leaving no one and nowhere behind Background • Tourism has explicitly mentioned as targets in Goal 8 (8.9.1 and 8.9.2). • In Indonesia, NSO (Statistics Indonesia collected and published the data regularly (Monthly and Annually) • There are data gaps, in terms of coverage, granularity (sub-national), timeliness • The data sources for inbound, domestic and outbound tourism are from immigration data, MPD, digital survey, and CAPI. #apstatsweek2020 Virtual Event 15-18 June 2020 2020 Asia-Pacific Statistics Week Leaving no one and nowhere behind Background • Indonesia hosted ASIAN Games in 2018, which was the second time after hosting it in 1962. • This multi sport event is hopefully could increase tourism and gave positive impact to the Indonesian economy and especially to regional/provincial economy in both short and long term. • The economic impact is analysed using Computable General Equlibrium (CGE) model #apstatsweek2020 Virtual Event 15-18 June 2020 2020 Asia-Pacific Statistics Week Leaving no one and nowhere behind Research Objectives The objective of this study is to analyze the mobility of people visiting the Asian Games 2018 in Jakarta and Palembang. -

The Effectiveness of Free Education Policy in Indonesia (A Case Study on the District of Musi Banyuasin South Sumatera)

The Effectiveness of Free Education Policy in Indonesia (A Case Study on the district of Musi Banyuasin South Sumatera) Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Department of Psychology, Mercu Buana University Jakarta Consultant of Bappenas Jakarta, 2011 Email : [email protected] Abstract This study aims to determine the effectiveness of the free educational program that has been conducted in Indonesian local government. This study investigates a case study on the implementation of free education in the district of Musi Banyuasin South Sumatera. The research was conducted qualitatively by analyzing secondary data and conduct interviews with stake holders whom are the executive of education from the Department of Education, the Principal and parents. From the research, it was found that the implementation of free education in Indonesia is still a political commodity, free education policy in practice still have problems and weaknesses. The constraints faced by schools is the budget provided by the local government is the cost of education and minimum service standards budget given are not payed monthly, but given every 6months which causes problems and obstacles in school operations, which then affects the school’s ability to thrive and compete with other schools. In the implementation of free education, the school is still collects school tuition fee from the parents through the school committee, this is because it takes a very large budget. Free schools policy also has psychological implications, where students and parents tend to be less concerned about the needs of the school, because they think everything is free, so the students have low interest and motivation, causing them to change schools freely because of the free education policy. -

A New Era in EU-China Relations: More Wide- Ranging Strategic Cooperation?

STUDY A new era in EU-China relations: more wide- ranging strategic cooperation? Policy Department for External Relations Author: Anna SAARELA EN Directorate General for External Policies of the Union DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY A new era in EU-China relations: more wide- ranging strategic cooperation? Author: Anna SAARELA ABSTRACT China is an important strategic partner for the EU, despite fundamental divergences in some areas, mostly related to state intervention and fundamental human rights. The partnership offers mutually beneficial cooperation and dialogue in areas ranging from investment and transport to human rights and cybersecurity. China is navigating in new directions, guided by Xi Jinping's 'Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’. Despite President Xi’s repeated avowals that 'the market will have a decisive role', public ownership remains the mainstay of the Chinese economy, whereas profound reforms would be needed to tackle the root causes of overcapacity in various industrial sectors. Xi's ‘Belt and Road Initiative’, now also included in the Constitution, is the flagship international connectivity and infrastructure programme dominated by Chinese state-owned companies. Overall, China’s crucial, but complex transition towards more sustainable growth would eventually benefit both, China and the world as a whole. Global economic interdependence, however, makes certain spill-over effects of China’s rebalancing unavoidable. China plays a pivotal role in global governance and the rules-based international order, and this comes with responsibilities. Beijing has begun to shift away from the narrow pursuit of national aims towards a more assertive foreign and security policy, and increased financial, economic and security cooperation with a global outreach.