Keeping Ethiopia's Transition on the Rails

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

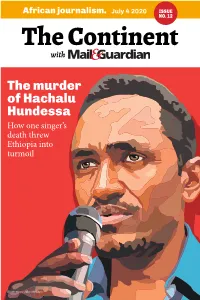

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Evidence of Social Media Blocking and Internet Censorship in Ethiopia

ETHIOPIA OFFLINE EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA BLOCKING AND INTERNET CENSORSHIP IN ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a global ABOUT OONI movement of more than 7 million The Open Observatory of Network Interference people who campaign for a (OONI) is a free software project under the Tor world where human rights are enjoyed Project that aims to increase transparency of internet censorship around the world. We aim to by all. empower groups and individuals around the world with data that can serve as evidence of internet Our vision is for every person to enjoy censorship events. all the rights enshrined in the Since late 2012, our users and partners around the Universal Declaration of Human world have contributed to the collection of millions of network measurements, shedding light on Rights and other international human multiple instances of censorship, surveillance, and rights standards. traffic manipulation on the internet. We are independent of any government, political We are independent of any ideology, economic interest or religion. government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Youth in Addis trying to get Wi-Fi Connection. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. ©Addis Fortune https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. -

Download the Pdf Version

Oromo Legacy Leadership PRESS RELEASE Oromoand Legacy Advocacy Leadership Association & Advocacy Association CONTACT US: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 07/23/2021 Senate Foreign Relations Committee Wants More Action to be Taken with African Allies FALLS CHURCH, VA (7/23/2021) – On July 20, 2021, U.S. Senator Jim Risch (R-Idaho), ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, made the following statement regarding the nomination of assistant secretary for African Affairs, the Honorable Mary Catherine Phee: “The Biden Administration has stated that “Africa is a priority,” but it’s unclear where Africa fits in that priority list.” He continues, “First, I am troubled by the conflict and humanitarian situation in Tigray. However, I am concerned that the U.S. is so focused on the Tigray crisis that it is ignoring the significant challenges to peace and democracy we face across Ethiopia. This is a complex challenge, I get that. I look forward to hearing how we navigate Ethiopia’s challenges and the other crises across the Horn of Africa which is becoming more and more of a focus and a crisis.” Mr. Risch is clear in his understanding that this is not strictly an Ethiopian issue, but a regional and global issue. The “complexity” includes the imprisonment of political opponents, such as Jawar Mohammed. “Jawar, a founder of the United States-based Oromia Media Network, was an ally of Abiy and played a key role in coordinating the protests that catapulted him to power, before becoming a public critic of his administration.” Mohammed and others were imprisoned following the violence that erupted throughout Ethipia after the murder of singer-songwriter Hachalu Hundessa on June 29, 2020. -

Ethiopia 2020 Human Rights Report

ETHIOPIA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ethiopia is a federal republic. The Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of four ethnically based parties, controlled the government until December 2019 when the coalition dissolved and was replaced by the Prosperity Party. In the 2015 general elections, the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front and affiliated parties won all 547 seats in the House of Peoples’ Representatives (parliament) to remain in power for a fifth consecutive five-year term. In 2018 former prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn announced his resignation to accelerate political reforms in response to demands from the country’s increasingly restive youth. Parliament then selected Abiy Ahmed Ali as prime minister to lead these reforms. Prime Minister Abiy leads the Prosperity Party. National and regional police forces are responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order, with the Ethiopian National Defense Force sometimes providing internal security support. The Ethiopian Federal Police report to the Ministry of Peace. The Ethiopian National Defense Force reports to the Ministry of National Defense. The regional governments (equivalent to a U.S. state) control regional security forces, which are independent from the federal government. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of all security forces committed some abuses. Abiy’s assumption of office was followed by positive changes in the human rights climate. The government decriminalized political movements that in the past were accused of treason, invited opposition leaders to return and resume political activities, allowed peaceful rallies and demonstrations, enabled the formation and unfettered operation of political parties and media outlets, and carried out legislative reform of repressive laws. -

Oromo Identi1y: Tiieorising Subjectivi1y and Ti-Ie Politics of Representation

The language of culture and the culture of language Oromo identity in Melbourne, Australia 4'-';•. ,=.:~ '-) -\'.'.\ .1 I . -- • ·. ~ u::--.xw ( j , •. : r--· ' i. ) ' \ J J/ \.<'1 ~· _-' <:__--;- __--* __ _,.,,-·_ Greg Gow Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Inquiry and Community Studies Faculty of Arts Victoria University of Technology 1999 Yaadannoo Oromoota dhabamaniifii kan maqaan isaani ifaa hin bahiniif warra waregnii issani Oromoota qoranna kanaa keysatii mullatan hadochu. Dedicated to the memory of the missing and unknown Oromo whose lives have touched the Oromo who feature in this thesis. DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my original work, except where otherwise cited, and has not been submitted, in whole or in part, for any other academic award. Greg Gow January 1999 CONTENTS Acknowledgments v A note on translation and the use of afaan Oromoo VJ Glossary Vil Abstract: by way of notes to the reader JX Mapping of Oromiya XJV PRELUDE A sort of homecoming 2 PART I REPRESENTING HOME: A LANGUAGE OF SUBJECTIVITY 1 Oromo identity: Theorising subjectivity and the politics of representation JO 2 What has home got to do with it? Being ethnographer and becoming-person 39 3 Oromo nationalist sensibilities: Silent enouncements and becoming-other 63 PART II PERFORMING HOME: A LANGUAGE OF MUSIC 4 Mana itti gaddin u hinqabn u-. The mourning of a 'nation' without a 'state' 91 5 Baddaan biyya tiyya: Musical aesthetics and the production of place 116 6 Ali Birraa keenya: The Legend continues 141 INTERLUDE 162 Imag(in)ing home (Plates 1-7) PART III MANAGING HOME: A LANGUAGE OF DISSONANCE 7 Manguddo sablocr. -

Notiz Äthiopien: Qeerroo-Bewegung Und Machtverhältnisse in Lokalverwaltungen Des Regionalstaats Oromia (07.05.2020)

Eidgenössisches Justiz- und Polizeidepartement EJPD Staatssekretariat für Migration SEM Sektion Analysen Öffentlich Bern-Wabern, 7. Mai 2020 Notiz Äthiopien Qeerroo-Bewegung und Machtverhältnisse in Lokalverwaltungen des Regionalstaats Oromia Öffentlich Inhaltsverzeichnis Fragestellung ....................................................................................................................... 3 Kernaussage ........................................................................................................................ 3 Main findings........................................................................................................................ 3 1. Quellenlage ............................................................................................................. 4 2. Die Qeerroo-Bewegung ......................................................................................... 4 3. Lage während der SEM-Abklärungsreise (Mai 2019) ........................................... 6 4. Jawar Mohammeds Hinwendung zum OFC ......................................................... 7 5. Lage in den Lokalverwaltungen Anfang 2020 ...................................................... 8 6. Kommentar ............................................................................................................. 9 6.1. Legitimität staatlichen Einschreitens......................................................................... 9 6.2. Ausblick .................................................................................................................. -

Ethiopia Offline Evidence of Social Media Blocking and Internet Censorship in Ethiopia

ETHIOPIA OFFLINE EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA BLOCKING AND INTERNET CENSORSHIP IN ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a global ABOUT OONI movement of more than 7 million The Open Observatory of Network Interference people who campaign for a (OONI) is a free software project under the Tor world where human rights are enjoyed Project that aims to increase transparency of internet censorship around the world. We aim to by all. empower groups and individuals around the world with data that can serve as evidence of internet Our vision is for every person to enjoy censorship events. all the rights enshrined in the Since late 2012, our users and partners around the Universal Declaration of Human world have contributed to the collection of millions of network measurements, shedding light on Rights and other international human multiple instances of censorship, surveillance, and rights standards. traffic manipulation on the internet. We are independent of any government, political We are independent of any ideology, economic interest or religion. government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Youth in Addis trying to get Wi-Fi Connection. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. ©Addis Fortune https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. -

Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net 2018

Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/ethiopia Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net Internet Freedom Score 13/25 Most Free (0) Least Free (100) Obstacles to access 23/25 Limits on content 29/35 Violations of users rights 31/40 Key Developments: May 31, 2017 - June 1, 2018 Internet access improved slightly though remained low during the coverage period (see Availability and Ease of Access). The government under former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn responded to ongoing antigovernment protests with frequent internet shutdowns and blocks on social media, though access was restored in April 2018 under the new prime minister (see Restrictions on Connectivity). A few blocked websites became accessible in May 2018, while hundreds more were unblocked in June, reflecting the new government’s openness to critical voices and independent news (see Blocking and Filtering). Online self-censorship decreased palpably as citizens flocked to social media to participate in their country’s transition from authoritarianism (see Media, Diversity, and Manipulation). Following the resignation of Prime Minister Desalegn, the authorities imposed a six-month state of emergency that placed restrictions on certain online activities to quell antigovernment unrest (see Legal Environment). In a positive step, the ruling EPRDF party released hundreds of political prisoners, including imprisoned bloggers, before his resignation—a trend that new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed continued. A few bloggers were arrested for short periods during the state of emergency (see Prosecutions and Arrests for Online Activities). Introduction: Internet freedom in Ethiopia remained highly restricted during the coverage period but saw incremental improvements following the resignation of former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn in February 2018 and the appointment of Abiy Ahmed to the seat in April. -

Media Freedom in Ethiopia WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedom in Ethiopia WATCH “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedom in Ethiopia Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32279 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JANUARY 2015 978-1-6231-32279 “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedoms in Ethiopia Glossary of Abbreviations ................................................................................................... i Map of Ethiopia .................................................................................................................. ii Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................