An Analysis of Selected Rhythmic, Harmonic and Melodic Devices Used in the Arrangement and Improvisation by Gwilym Simcock on the Way You Look Tonight (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allan Holdsworth Schille Reshaping Harmony

BJØRN ALLAN HOLDSWORTH SCHILLE RESHAPING HARMONY Master Thesis in Musicology - February 2011 Institute of Musicology| University of Oslo 3001 2 2 Acknowledgment Writing this master thesis has been an incredible rewarding process, and I would like to use this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to those who have assisted me in my work. Most importantly I would like to thank my wonderful supervisors, Odd Skårberg and Eckhard Baur, for their good advice and guidance. Their continued encouragement and confidence in my work has been a source of strength and motivation throughout these last few years. My thanks to Steve Hunt for his transcription of the chord changes to “Pud Wud” and helpful information regarding his experience of playing with Allan Holdsworth. I also wish to thank Jeremy Poparad for generously providing me with the chord changes to “The Sixteen Men of Tain”. Furthermore I would like to thank Gaute Hellås for his incredible effort of reviewing the text and providing helpful comments where my spelling or formulations was off. His hard work was beyond what any friend could ask for. (I owe you one!) Big thanks to friends and family: Your love, support and patience through the years has always been, and will always be, a source of strength. And finally I wish to acknowledge Arne Torvik for introducing me to the music of Allan Holdsworth so many years ago in a practicing room at the Grieg Academy of Music in Bergen. Looking back, it is obvious that this was one of those life-changing moments; a moment I am sincerely grateful for. -

Printmakers Presspack

THE PRINTMAKERS “In the old days, this band would have had the words “All-Stars” in their name. Every one of them is a leading figure in British contemporary jazz. Together, they create 10 evocative sound-pictures of places and times. It’s remarkable how just five instruments and voice can suggest space and depth as they do.” Dave Gelly, The Observer The word supergroup is common currency, especially in the rock world. Jazz, of course, has its fair share of supergroups too. Sometimes, one supergroup comes along that really is very special indeed. The Printmakers is such a group. The group formed at the instigation of Steve Mead at The Manchester Jazz Festival several years ago and since then has gone from strength to strength. Award winning Nikki Iles is one of the heroines of British jazz. She has made an invaluable contribution to the jazz scene in this country and beyond, while also making a very personal musical statement in many groups, not least her own superb Anglo-American trio with Rufus Reid and Jeff Williams. Grammy nominated and ECM recording artist Norma Winstone MBE, pioneering innovator of the voice, has been a leading light in European music for many years. She collaborated with Kenny Wheeler and John Taylor in Azimuth, described by Richard Williams as “one of the most imaginatively conceived and delicately balanced of all contemporary chamber jazz groups“. She has also worked with Fred Hersch, Steve Swallow, Jimmy Rowles, Mike Gibbs and Ralph Towner. She has had a resurgence recently, with three superb award winning ECM releases in collaboration with European musicians, Klaus Gesing and Glauco Venier. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

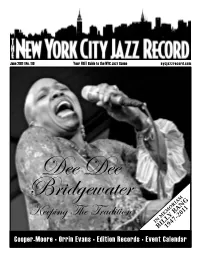

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Gwilym Simcock

Gwilym Simcock Chick Corea simply calls him an "original. A creative genius", while Jamie Cullum raves about his playing: "I'll be watching our finest young piano-player Gwilym Simcock." Born 1981 in Wales, Simcock – now living in London –is undoubtedly right at the top of European jazz and considered one of the most gifted pianists and imaginative composers on the British scene. He took classical piano lessons at one of England's most renowned music schools from the age of three, building up a musical background that defines his playing to this day. He certainly could have become a successful classical pianist if he had not discovered Keith Jarrett's and Pat Metheny's music by the age of 15, finally drawing him into jazz. Having completed his studies at the Royal Academy of Music he is able to move effortlessly between jazz and classical. Simcock was acknowledged as a great talent very early on and soon got to play with stars like Dave Holland, Lee Konitz, Bob Mintzer and on Bill Bruford's "Earthworks". Winner of the Perrier Award, BBC Jazz Awards and British Jazz Awards in 2005, Simcock was the first BBC Radio 3 "New Generation Jazz Artist". He also was voted "Jazz Musician of the Year" at the 2007 Parliamentary Jazz Awards. The release of his ACT debut "Good Days at Schloss Elmau" (ACT 9501-2) early in 2011 marks his final breakthrough. Along with recordings by Adele, Katy B and James Blake, the solo piano album was nominated for the prestigious Mercury Prize as one of Great Britain's 12 best albums of the year. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lockett, P.W. (1988). Improvising pianists : aspects of keyboard technique and musical structure in free jazz - 1955-1980. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8259/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] IMPROVISING PIANISTS: ASPECTS OF KEYBOARD TECHNIQUE AND MUSICAL STRUCTURE IN FREE JAll - 1955-1980. Submitted by Mark Peter Wyatt Lockett as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University Department of Music May 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No I List of Figures 3 IIListofRecordings............,........ S III Acknowledgements .. ..... .. .. 9 IV Abstract .. .......... 10 V Text. Chapter 1 .........e.e......... 12 Chapter 2 tee.. see..... S S S 55 Chapter 3 107 Chapter 4 ..................... 161 Chapter 5 ••SS•SSSS....SS•...SS 212 Chapter 6 SS• SSSs•• S•• SS SS S S 249 Chapter 7 eS.S....SS....S...e. -

An Evening with Pat Metheny with Antonio Sánchez, Linda May Han Oh, and Gwilym Simcock

Thursday, October 25, 2018, 8pm Fox Theater, Oakland An Evening with Pat Metheny with Antonio Sánchez, Linda May Han Oh, and Gwilym Simcock Cal Performances’ 2018 –19 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Pat Metheny was born in Lee’s Summit (MO) on one of the very first jazz musicians to treat the August 12, 1954, into a musical family. Starting synthesizer as a serious musical instrument. on trumpet at the age of eight, he switched to Years before the invention of MIDI technology, guitar at age 12. By the age of 15, he was work - Metheny was using the Synclavier as a compos - ing regularly with the best jazz musicians in ing tool. He has also been instrumental in the Kansas City, receiving valuable on-the-band - development of several new kinds of guitars, in - stand experience at an unusually young age. cluding the soprano acoustic guitar, the 42-string Metheny first burst onto the international jazz Pikasso guitar, Ibanez’s PM series of jazz guitars, scene in 1974. Over the course of his three-year and a variety of other custom instruments. stint with vibraphone great Gary Burton, the It is one thing to attain popularity as a musi - young Missourian quickly displayed his soon- cian, but it is another to receive the kind of to-become trademark playing style, which acclaim Metheny has garnered from critics and blends the loose and flexible articulation peers. Over the years, he has won countless polls customarily reserved for horn players with an as Best Jazz Guitarist along with awards includ - advanced rhythmic and harmonic sensibility— ing gold records for (Still Life) Talking, Letter a way of playing and improvising that is mod - from Home, and Secret Story . -

Joe's Guitar Method Towards a Jazz Improviser's Technique

Joe’s Guitar Method Towards A Jazz Improviser’s Technique I. Intro Pg. 1 II. Tuning & Setup Pg. 5 A. The Grand Staff B. Using a Tuner C. Intonation D. Action and String Gauges E. About Whammy Bars III. Learning The Fretboard Pg. 11 A. The C Major Scale....(how to find the “natural” pitches on each string) IV. Basic Guitar Techniques Pg. 13 A. Overview B. Holding the Pick C. Fretting Hand: Placement of the Fingers D. String Dampening E. Fretting Hand: Placement Of the Thumb F. Fretting Hand: Finger Stretches G. Fretting Hand: The Wrist (About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome) H. Position Playing on Single Strings V. Single String Exercises Pg. 19 A. 6th String B. 5th String C. 4th String D. 3rd String E. 2nd String F. 1st String G. Phrasing Possibilities On A Single String VI. Chords: Construction/Execution/Basic Harmony Pg. 35 A. Triads 1. Construction 2. Movable Triadic Chord Forms a) Freddie Green Style - Part 1 (1) Strumming (2) Pressure Release Points (3) Rhythm Slashes (4) Changing Chords 3. Inversions 4. Open Position Major Chord Forms 5. Open Position - Other Triadic Chords a) Palm Mutes B. Seventh Chords 1. Construction 2. Movable Seventh Chord Forms 3. Open Position Seventh Chord Forms C. Chords With Added Tensions 1. Construction D. Simple Diatonic Harmony E. Elementary Voice Leading F. Changes To Some Standard Tunes 1. All The Things You Are 2. Confirmation 3. Rhythm Changes 4. Sweet Georgia Brown 5. All Of Me 5. All Of Me VII. Open Position Pg. 69 A. Overview B. Picking Techniques 1. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Bio Information: JOEL HARRISON, LORENZO FELICIATI, CUONG VU, ROY POWELL, DAN WEISS Title: HOLY ABYSS (Cuneiform Rune 334)

Bio information: JOEL HARRISON, LORENZO FELICIATI, CUONG VU, ROY POWELL, DAN WEISS Title: HOLY ABYSS (Cuneiform Rune 334) Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ “When you stare into the abyss the abyss stares back at you.” – Friedrich Nietzsche Full of foreboding and existential terror, the abyss resides in the darkest corners of the human imagination. Holy Abyss, a collaborative project between New York guitarist Joel Harrison and Italian bassist Lorenzo Feliciati, is an antidote to angst. Flowing from a deep communion between the artists, the album turns dread on its head, offering a series of expansive soundscapes full of lustrous harmonies, searching melodies and knowing interplay. Featuring trumpeter Cuong Vu, drummer Dan Weiss and Roy Powell on piano and Hammond B3 organ, the quintet reflects jazz’s increasingly international reach. Harrison and Weiss, musical comrades for many years, are New Yorkers, while longtime collaborators Feliciati and Powell hail from Rome and Oslo via the UK, respectively. Vu, who has toured and recorded with Feliciati and Powell, was born in Vietnam and is now based in Seattle, near where he grew up. The musicians are united by a passion for modern jazz unbounded by stylistic conventions. Open to sounds from around the world, they have all created music infused with electronics, odd meters, and uncommon timbres and tonal palettes. Holy Abyss opens with Harrison’s anguished ballad “Requiem for an Unknown Soldier,” which establishes the album’s elemental sensibility with its ethereal trumpet fanfare and slow burning guitar solo. -

Omer Avital Ed Palermo René Urtreger Michael Brecker

JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM special feature BEST 2014OF ICP ORCHESTRA not clowning around OMER ED RENÉ MICHAEL AVITAL PALERMO URTREGER BRECKER Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Omer Avital by brian charette Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Ed Palermo 7 by ken dryden [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : ICP Orchestra 8 by clifford allen [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : René Urtreger 10 by ken waxman Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Michael Brecker 10 by alex henderson VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Smoke Sessions 11 by marcia hillman [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, CD Reviews 14 Katie Bull, Tom Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Special Feature: Best Of 2014 28 Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Miscellany Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Robert Milburn, Russ Musto, Event Calendar 44 Sean J. O’Connell, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman As a society, we are obsessed with the notion of “Best”.