Sharing the Land with Pinyon-Juniper Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Juniper Woodlands of the Pacific Northwest

Western Juniper Woodlands (of the Pacific Northwest) Science Assessment October 6, 1994 Lee E. Eddleman Professor, Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Patricia M. Miller Assistant Professor Courtesy Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Richard F. Miller Professor, Rangeland Resources Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center Burns, Oregon Patricia L. Dysart Graduate Research Assistant Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... i WESTERN JUNIPER (Juniperus occidentalis Hook. ssp. occidentalis) WOODLANDS. ................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 Current Status.............................................. 2 Distribution of Western Juniper............................ 2 Holocene Changes in Western Juniper Woodlands ................. 4 Introduction ........................................... 4 Prehistoric Expansion of Juniper .......................... 4 Historic Expansion of Juniper ............................. 6 Conclusions .......................................... 9 Biology of Western Juniper.................................... 11 Physiological Ecology of Western Juniper and Associated Species ...................................... 17 Introduction ........................................... 17 Western Juniper — Patterns in Biomass Allocation............ 17 Western Juniper — Allocation Patterns of Carbon and -

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph taken by Richard F. Miller. Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions By R.F. Miller, Oregon State University, J.D. Bates, T.J. Svejcar, F.B. Pierson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and L.E. Eddleman, Oregon State University This is contribution number 01 of the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP), supported by funds from the U.S. Joint Fire Science Program. Partial support for this guide was provided by U.S. Geological Survey Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials con- tained within this report. Suggested citation: Miller, R.F., Bates, J.D., Svejcar, T.J., Pierson, F.B., and Eddleman, L.E., 2007, Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions: U.S. -

Behavioral Profiles

Terra Explorer Volume 1 The Terra Explorer series is copyrighted © 2009 by William James Davis. All rights reserved. Copyrights of individual stories in- cluded in the last section of the book, “Adventures in the field,” belong to their respective authors. (see following page for more details) William James Davis, Ph.D. Copyright © 2009 by Wm. James Davis ISBN 978-0-9822654-0-6 0-9822654-0-9 Also available as an eBook. To order, visit: http://www.TerraNat.com The Terra Explorer series is copyrighted © 2009 by William James Davis. All rights reserved. Copyrights of individual stories included in the last section of the book, “Adventures in the field,” belong to their respective authors. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher and respective authors, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Contact the publisher to request permis- sion by visiting www.terranat.com. Photos on the front and back covers (Black Skimmer and Cuban Anole, respec- tively) by Karen Anthonisen Finch. For Linda Jeanne Mealey, who inspired my dreams to explore the natural world. Also by William James Davis Australian Birds: A guide and resource for interpreting behavior TableTable of of contents contents Introduction Evolution of a concept The challenge Book’s organization and video projects Participating in the Terra Explorer Project Behavioral profiles 8 Common Loon 11 American White Pelican 14 Anhinga 17 Cattle Egret 20 Mallard 23 Bald Eagle 26 -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

The Cognitive Animal Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition

This PDF includes a chapter from the following book: The Cognitive Animal Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition © 2002 Massachusetts Institute of Technology License Terms: Made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ OA Funding Provided By: The open access edition of this book was made possible by generous funding from Arcadia—a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. The title-level DOI for this work is: doi:10.7551/mitpress/1885.001.0001 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/books/edited-volume/chapter-pdf/677490/9780262268028_c001600.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 17 Spatial and Social Cognition in Corvids: An Evolutionary Approach Russell P. Balda and Alan C. Kamil research plan using controlled laboratory ex- Research Questions periments and captive birds. Fortunately, nut- crackers are quite willing to cache and recover The central research questions that have guided seeds in laboratory settings and do so with a high our studies since 1981 combine issues and tech- degree of accuracy, both in a sandy floor indoors niques from both comparative psychology and (Balda 1980; Balda and Turek 1984) or out of avian ecology. Most of our questions originate doors (Vander Wall 1982), as well as in a room from the cognitive implications of extensive field with a raised floor containing sand-filled cups as studies on the natural history, ecology, and potential cache sites (Kamil and Balda 1985). behavior of seed-caching corvids. Because our The ability to study caching and cache recovery questions have evolved as our studies progressed, under controlled laboratory conditions allowed we have chosen to give a historical perspective us to test hypotheses on how the nutcrackers find outlining the progression of our ideas and ques- their caches. -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Merging Science and Management in a Rapidly Changing World: Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean (Q

Preliminary Assessment of Species Richness and Avian Community Dynamics in the Madrean Sky Islands, Arizona Jamie S. Sanderlin, William M. Block, Joseph L. Ganey, and Jose M. Iniguez U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, Arizona Abstract—The Sky Island mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona contain a unique and rich avifaunal community, including many Neotropical migratory species whose northern breeding range extends to these mountains along with many species typical of similar habitats throughout western North America. Understand- ing ecological factors that influence species richness and biological diversity of both resident and migratory species is important for conservation of this unique bird assemblage. We used a 5-year data set to evaluate avian species distribution across montane habitat types within the Santa Rita, Santa Catalina, Huachuca, Chiricahua, and Pinaleño Mountains. Using point-count data from spring-summer breeding seasons, we de- scribe avian diversity and community dynamics. We use a Bayesian hierarchical model to describe occupancy as a function of vegetative cover type and mountain range latitude, and detection probability as a function of species heterogeneity and sampling effort. By identifying important habitat correlates for avian species, these results can help guide management decisions to minimize loss of key habitats and guide restoration efforts in response to disturbance events in the Madrean Archipelago. Introduction We studied occupancy and cover type associations of forest birds across montane vegetative cover types in the Santa Rita, Santa The Sky Island mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona, USA, Catalina, Huachuca, Chiricahua, and Pinaleño Mountains of south- contain a unique and rich avifaunal community. -

Sacred Heart Game.Pmd

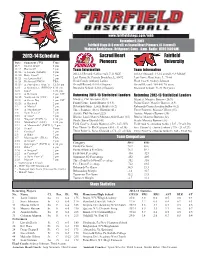

www.fairfieldstags.com/mbb November 9, 2013 Fairfield Stags (0-0 overall) vs Sacred Heart Pioneers. (0-0 overall) Webster Bank Arena - Bridgeport, Conn. - 8 pm - Radio : WICC (600 AM) 2013-14 Schedule Sacred Heart Fairfield Date Opponent (TV) Time Pioneers University 11/9 Sacred Heart! 8 pm 11/13 Hartford# 7 pm Team Information Team Information 11/16 at Loyola (MASN) 8 pm 11/20 Holy Cross# 7 pm 2012-13 Record: 9-20 overall, 7-11 NEC 2012-13 Record: 19-16 overall, 9-9 MAAC 11/23 vs. Louisville#^ 2 pm Last Game: St. Francis Brooklyn, L, 80-92 Last Game: Kent State, L, 73-60 11/24 Richmond/UNC#^ TBA Head Coach: Anthony Latina Head Coach: Sydney Johnson 11/29 at Providence (Fox 1) 12:30 pm Overall Record: 0-0 (1st Season) Overall Record: 105-84 (7th year) 12/6 at Quinnipiac (ESPN3)* 8:30 pm Record at School: 0-0 (1st Season) Record at School: 41-31 (3rd year) 12/8 Iona* 1:30 pm 12/11 at Belmont 7 pm CST Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders 12/15 Northeastern (SNY) 1 pm 12/21 at Green Bay 1 pm CST Minutes: Phil Gaetano (35.3) Minutes: Maurice Barrow (26.9) 12/28 at Bucknell 2 pm Points/Game: Louis Montes (14.4) Points/Game: Maurice Barrow (8.9) 1/2 at Marist* 7 pm Rebounds/Game: Louis Montes (6.2) Rebounds/Game:Amadou Sidibe (6.2) 1/4 at Manhattan* 7 pm Three Pointers: Steve Glowiak (61) Three Pointers: Marcus Gilbert (35) 1/8 Saint Peter’s* 7 pm Assists: Phil Gaetano (222) Assists: Maruice Barrow (38) 1/10 at Iona* 7 pm Blocks: Louis Montes/Mostafa Abdel Latif (15) Blocks: Maurice Barrow (22) 1/16 Niagara* -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

Phylogenetic Analyses of Juniperus Species in Turkey and Their Relations with Other Juniperus Based on Cpdna Supervisor: Prof

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGY APRIL 2015 Approval of the thesis MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA submitted by AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Biological Sciences, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Gülbin Dural Ünver Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Orhan Adalı Head of the Department, Biological Sciences Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Supervisor, Dept. of Biological Sciences METU Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Musa Doğan Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof.Dr. Hayri Duman Biology Dept., Gazi University Prof. Dr. İrfan Kandemir Biology Dept., Ankara University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sertaç Önde Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Date: iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Aysun Demet GÜVENDİREN Signature : iv ABSTRACT MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA Güvendiren, Aysun Demet Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences Supervisor: Prof. -

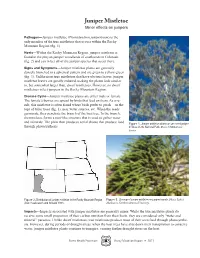

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor.