Advanced Non-Fiction Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Member Motion City Council MM20.14

Member Motion City Council Notice of Motion MM20.14 ACTION Ward:19 Creation and Installation of a Plaque Commemorating The People’s Champion - Muhammad Ali - by Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam * Notice of this Motion has been given. * This Motion is subject to referral to the Executive Committee. A two-thirds vote is required to waive referral. Recommendations Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam, recommends that: 1. City Council increase the approved 2016 Operating Budget for Heritage Toronto by $3,250 gross, $0 net, fully funded by Section 37 community benefits obtained in the development at 700 King Street West (Source Account: XR3026-3700113), for the production and installation of a plaque commemorating the life and career in Toronto of Muhammad Ali. 2. City Council direct that the funds be transferred to Heritage Toronto subject to the condition that the Historical Plaques Committee of Heritage Toronto approve of the plaque subject matter. Summary Heritage Toronto is working with local residents to commemorate Muhammad Ali's 1966 visit to Toronto, including his fight against George Chuvalo. Muhammed Ali was one of the world's most celebrated athletes, best-known personalities, and influential civil rights activists. Ali’s enduring fight against oppression and involvement in the black freedom struggle is part of what brought him to Toronto. In March 1966, Ali was booked to fight Ernie Terrell in Chicago, but his controversial anti-war views and refusal to join the United States draft resulted in Chicago and every major United States boxing centre refusing to host the fight, forcing the organizers to move it to Toronto and arrange an alternative opponent - Canadian heavyweight champion, George Chuvalo. -

Muhammad Ali, Daily Newspapers, and the State, 1966-1971

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2004 Imagining Dissent: Muhammad Ali, Daily Newspapers, and the State, 1966-1971 Daniel Bennett Coy University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Coy, Daniel Bennett, "Imagining Dissent: Muhammad Ali, Daily Newspapers, and the State, 1966-1971. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1925 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Daniel Bennett Coy entitled "Imagining Dissent: Muhammad Ali, Daily Newspapers, and the State, 1966-1971." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. George White, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Cynthia Fleming, Janis Appier Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Daniel Bennett Coy entitled “Imagining Dissent: Muhammad Ali, Daily Newspapers, and the State, 1966-1971.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. -

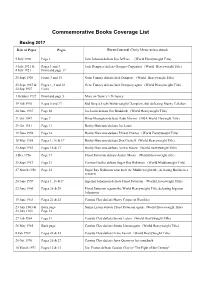

Boxing Edition

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Muhammad Ali Biography

Muhammad Ali Biography “I’m not the greatest; I’m the double greatest. Not only do I knock ’em out, I pick the round. “ – Muhammad Ali Short Biography Muhammad Ali Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. on January 17, 1942) is a retired American boxer. In 1999, Ali was crowned “Sportsman of the Century” by Sports Illustrated. He won the World Heavyweight Boxing championship three times, and won the North American Boxing Federation championship as well as an Olympic gold medal. Ali was born in Louisville, Kentucky. He was named after his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., (who was named for the 19th century abolitionist and politician Cassius Clay). Ali later changed his name after joining the Nation of Islam and subsequently converted to Sunni Islam in 1975. Early boxing career Standing at 6’3″ (1.91 m), Ali had a highly unorthodox style for a heavyweight boxer. Rather than the normal boxing style of carrying the hands high to defend the face, he instead relied on his ability to avoid a punch. In Louisville, October 29, 1960, Cassius Clay won his first professional fight. He won a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker, who was the police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia. From 1960 to 1963, the young fighter amassed a record of 19-0, with 15 knockouts. He defeated such boxers as Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark (who had won his previous 40 bouts by knockout), Doug Jones, and Henry Cooper. Among Clay’s victories were versus Sonny Banks (who knocked him down during the bout), Alejandro Lavorante, and the aged Archie Moore (a boxing legend who had fought over 200 previous fights, and who had been Clay’s trainer prior to Angelo Dundee). -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952 -

Muhammad Speaks and Muhammad Ali Intersections of the Nation of Islam and Sport in the 1960S Maureen Smith

10 Muhammad Speaks and Muhammad Ali Intersections of the Nation of Islam and sport in the 1960s Maureen Smith America, more than any other country, offers our people opportunities to engage in sports and play, which cause delinquency, murder, theft, and other forms of wicked and immoral crimes. This is due to this country’s display of filthy temptations in this world of sport and play.1 Introduction With the advent of its first issue, Muhammad Speaks established itself as the voice of the Nation of Islam’s Messenger, Elijah Muhammad. Dedicated to ‘Freedom, Justice, and Equality for the Black Man’, the first issue was printed in October 1961 and the newspaper’s circulation increased at a rate comparable to the discontent of African Americans in the USA during the freedom struggle of the civil rights movement.2 Advocating freedom and separation from whites, the newspaper served a critical role in promoting racial pride, as well as ministering the beliefs and teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Some of these teachings explored issues surrounding a range of athletic pursuits, and initially the Nation rejected the ‘evils’ of professional sport and games. Yet, through the pages of Muhammad Speaks it is possible to identify a shift in the Nation of Islam’s position on sport, as the organisation’s leadership came to recognise the political utility that an association with a prominent Muslim athlete, such as Muhammad Ali, could offer their movement. Once Ali’s use to the Nation of Islam was exhausted, the leaders once again resumed their opposition to professional sport. -

Muhammad Ali's Main Bout: African American Economic Power and The

1 Muhammad Ali’s Main Bout: African American Economic Power and the World Heavyweight Title—by Michael Ezra Muhammad Ali announced at a press conference in January 1966 that he had formed a new corporation called Main Bout, Inc. to manage the multi-million-dollar promotional rights to his fights. “I am vitally interested in the company,” he said, “and in seeing that it will be one in which Negroes are not used as fronts, but as stockholders, officers, and production and promotion agents.” Although racially integrated, Main Bout was led by the all-black Nation of Islam. Its rise to this position gave African Americans control of boxing’s most valuable prize, the world heavyweight championship. Ali envisioned Main Bout as an economic network; a structure that would generate autonomy for African Americans. Main Bout encountered resistance from the beginning. It came initially from white sportswriters. But about a month after Main Bout’s formation Ali’s draft status changed to 1-A, which meant that he had become eligible for military service in the Vietnam War. When Ali then opposed the war publicly, politicians nationwide joined the press in attacking Main Bout. The political controversy surrounding Ali made it easier for Main Bout’s economic competitors— rival promoters, closed-circuit television theater chains, and organized crime—to run the organization out of business. Money and politics were important elements of white resistance to Main Bout as was the organization’s potential as a black power symbol. Like his civil rights contemporaries, Muhammad Ali understood the importance of economic power. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction

Auction 241 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A BOXING 19 Trophy shield with brass boxer and plaque 'Bomber Command, Boxing Championships 1938, Fly, Runner Up, EH Richards'; plus boxing posters (12) including 'Fenech v Calvin Grove' (1993) signed by Jeff Fenech. 100 Ex Lot 20 - Extract 20 Photographs including Bob Fitzsimmons, Les Darcy (5 - including one of Darcy as a blacksmith's apprentice and another of Darcy's funeral cortege), Dave & Clem Sands, Joe Louis, Vic Patrick (4), and a bloodied Jimmy Carruthers. (14) 350 21 Share Certificate 'The National Sporting Club Limited', share certificate No.12 for one share owned by B Glass, dated 11th Feb.1905. Signed by Sec R Isaacs & Director S Myers, with handstamps 'The National Sporting Club Limited, Melbourne'. Folded up into small green leather holder with a diamond faced window. [The club opened in Sydney in October 1902 with the heavyweight boxing championship of Australasia, McColl v Doherty, but collapsed in 1906]. 100 Ex Lot 22 22 Photographs signed by Jersey Joe Walcott, Don King, Larry Holmes, Ingemar Johansson, Floyd Patterson, Joe Frazier, Archie Moore, Sugar Ray Leonard & Johnny Famechon. (9) 200 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au Apr 18, 2020 BOXING (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Ex Lot 23 - Extract 23 JOHNNY FAMECHON: Original fight poster for Featherweight Championship of the World, Jose Legra v Johnny Famechon, at Royal Albert Hall in London on 21.1.1969 (also includes Joe Bugner v Rudolph Vaughan), laminated, framed & glazed, overall 49x68cm; together with flyer for fight signed by Johnny Famechon (with originally scheduled date 3.12.1968) & ticket to this fight. -

GAY TALESE the SILENT SEASON of a HERO Punctuated by Hard Gasps of His Breathing-"Hegh-Hegh When He Was the Champion, and Also a Television Set

THE LOSER Esquire, 1964 T THE FooT of a mountain in upstate New York, about A sixty miles from Manhattan, there is an abandoned coun try clubhouse with a dusty dance floor, upturned bar stools, and an untuned piano; and the only sounds heard around the place at night come from the big white house behind it-the clanging sounds of garbage cans being toppled by raccoons, skunks, and stray cats making their nocturnal raids down from the mountain. The white house seems deserted, too; but occasionally, when the animals become too clamorous, a light will flash on, a win dow will open, and a Coke bottle will come flying through the darkness and smash against the cans. But mostly the animals are undisturbed until daybreak, when the rear door of the white house swings open and a broad-shouldered Negro appears in gray sweat clothes with a white towel around his neck. He runs down the steps, quickly passes the garbage cans, and proceeds at a trot down the dirt road beyond the country club toward the highway. Sometimes he stops along the road and throws a flurry of punches at imaginary foes, each jab 141 GAY TALESE THE SILENT SEASON OF A HERO punctuated by hard gasps of his breathing-"hegh-hegh when he was the champion, and also a television set. The setis hegh "-and then, reaching the highway, he turns and soon usually on except when Patterson is sleeping, or when he is ... disappears up the mountain. sparring across the road inside the clubhouse (the ring is rigged At this time of morning farm trucks are on the road, and the over what was once the dance floor), or when, in a rare mo drivers wave at the runner. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

Walter Iooss Edition Quantity Is Unlimited Unless Otherwise Noted

WA LT ER IOOSS 43 GALLERY Prints FOR PURCHASE Signed by Walter Iooss edition quantity is unlimited unless otherwise noted. Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier Michael Jordan Michelle Kwan Philadelphia, PA, 2003 Highland Park, IL, 1998 New York, NY, 1997 Digital Pigment Print From an Digital Pigment Print From an Digital Pigment Print Original 20 x 24 Polaroid Original 4 x 5 Polaroid dimensions price dimensions price dimensions price 16 x 20 $3,000 20 x 24 $5,000 20 x 24 $4,500 20 x 24 $4,000 30 x 40 $6,000 37 x 47½ $10,000 ed. qty. 15 40 x 60 $10,000 ed. qty. 15 Tom Brady Ray Lewis Terrell Owens New England Patriots Baltimore Ravens San Francisco 49ers Detroit, MI, 2006 Baltimore, MD, 2002 San Francisco, CA, 2002 Digital Pigment Print From an Digital Pigment Print From an Digital Pigment Print From an Original 20 x 24 Polaroid Original 8 x 10 Polaroid Original 8 x 10 Polaroid dimensions price dimensions price dimensions price 20 x 24 $4,000 16 x 20 $3,000 16 x 20 $3,000 20 x 24 $4,000 20 x 24 $4,000 edition quantity is unlimited unless otherwise noted. NEED IMAGE Tony Scott and Garry Templeton Joe Montana “The Catch” —San Francisco 49er Dwight St. Louis Cardinals San Francisco 49ers Clark catches the winning touchdown. Dodger Stadium San Francisco, CA, 1991 San Francisco, CA, 1982 Los Angeles, CA, 1979 Digital Pigment Print Digital Pigment Print Digital Pigment Print dimensions price dimensions price dimensions price 16 x 20 $3,000 16 x 20 $4,000 16 x 20 $3,000 20 x 24 $4,000 20 x 24 $5,000 20 x 24 $4,000 30 x 40 $6,000 30 x 40 $7,000 Young Kickboxer Rhythmic Gymnast Yogi Berra and Whitey Ford Bangkok, Thailand, 1995 Havana, Cuba, 1999 Spring Training Tampa Bay, FL, 2001 Digital Pigment Print Digital Pigment Print Digital Pigment Print From an dimensions price dimensions price Original 8 x 10 Polaroid 16 x 20 $3,000 16 x 20 $3,000 20 x 24 $4,000 20 x 24 $4,000 dimensions price 30 x 40 $6,000 16 x 20 $3,000 20 x 24 $4,000 30 x 40 $6,000 edition quantity is unlimited unless otherwise noted. -

Although Filmed in Black and White, the Film Is Gorgeously Rich in Texture

Although filmed in black and white, As The Heart of the the film is gorgeously rich in texture World proved, Maddin with tones of greens, purples, blues is—as one review in and, appropriately enough, bright The New York Times stabs of crimson. And while essential- described him—the ly a silent drama, beneath the swirling "finest black–and–white Gustav Mahler soundtrack there's silent director in all of the gentle sound of fangs piercing a Canada." Dracula: Pages virgin's neck and the sickening thwack from a Virgin's Diary is of a wooden stake being driven another feather in his through Dracula's heart. Maddin cap and this reviewer has not so much made a record of a eagerly anticipates his next foray into Pretenders beware, Maddin is pre- stage production; rather, he has feature filmmaking, The Saddest Music pared once again to claim his rightful re–imagined Stoker's Dracula as it in the World (based on an original place as Canada's most original and might have looked before the likes screenplay by Kazuo Ishigura), a daring auteur. of Bela Lugosi and Francis Ford Rhombus Media production that will Coppola got a hold of it. be unleashed on the world in the fall. By Paul Townend Paul Townend is a Toronto-based freelance film critic and editor. 2003 100m prod NFB, exp Sylvia Sweeney, Louise Lore, p Silva Basmajian, d Joseph Blasioli, sc Stephen Brunt, ph Michael Ellis, ed Craig Bateman, s John Martin, mus Allan Kane, narr Colin Linden; with Muhammad Ali, George Chuvalo, Milt Dunnell, Angelo Dundee, Robert Lipsyte, Rachman Ali, Iry Ungerman, Jimmy Breslin, Bert Sugar, Ernie Terrell.