Aethlon: the JOURNAL of SPORT LITERATURE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsnfiwvsimr TIRES Te«Gg?L

DUE TO NEIGHBORHOOD PRESSURE Tulloch, Aussie Mays Unable to Buy Terps Fly to Face " i-', j 5 '*¦ 1 ' '''''¦- r_ ?-‘1 San Francisco Home Wonder Horse, Tough Miami Battle By MERRELL WHITTLESEY burgh remaining on their SAN FRANCISCO. Nov. 14 want you. what's the good of Star Staff Correspondent schedule. |H (JP>. —Willie Mays’ attempt to buying,’’ Mays continued. MIAMI, Nov. 14—For the Coming to U. This comeback has placed / S. yester- buy a house here failed ’’Blittalk about a thing like second straight week Maryland the Hurricanes on the list of day Jjecause he is a Negro. this goes all over the world, SYDNEY, Australia, Nov. 14 is facing a predominantly eligibles P).—Tulloch, Australia’s for Jacksonville’s The spectacular, 27-year-old and it sure looks bad for our 0 1 new young team with a late-season Gator Bowl, providing, of of San ; country.” wonder horse which is being kick when the Terps meet course, centerflelder the Fran- greater they win their last three cisco Giants offered the $37,- Mays’ wife, Marghuerite, acclaimed as than the | Miami here tomorrow night. It games. quite as philosophical famous Pliar Lap. is ,being 500 asked by the owner for a ; wasn't bears out Coach Tommy Mont's Gator Bowl officials new house 175 Miraloma about It. “Down in Alabama readied foj a campaign in the earlier statement listed at States, ; that this Miami as one of nine teams un- drive, but was turned down where we come from,” she United with the ulti- year's schedule should have mate a der consideration. -

The Color Line in Midwestern College Sports, 1890–1960 Author(S): Charles H

Trustees of Indiana University The Color Line in Midwestern College Sports, 1890–1960 Author(s): Charles H. Martin Source: Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 98, No. 2 (June 2002), pp. 85-112 Published by: Trustees of Indiana University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27792374 . Accessed: 04/03/2014 22:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Trustees of Indiana University and Indiana University Department of History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Magazine of History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 35.8.11.3 on Tue, 4 Mar 2014 22:07:54 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Samuel S. Gordon, Wabash College, 1903 Ramsay Archival Center This content downloaded from 35.8.11.3 on Tue, 4 Mar 2014 22:07:54 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Color Line inMidwestern College Sports, 1890-1960 Charles H. Martin'1 On a cold afternoon in late November 1903, an overflow football crowd on the campus ofWabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, grew restless when the end of the season contest against archrival DePauw College failed to start on time. -

SONNY LISTON and the TORN TENDON Arturo Tozzi, MD, Phd

SONNY LISTON AND THE TORN TENDON Arturo Tozzi, MD, PhD, AAP Center for Nonlinear Science, University of North Texas, PO Box 311427, Denton, TX 76203-1427, USA [email protected] The first Liston-Clay fight in 1964 is still highly debated, because Liston quitted at the end of the sixth round claiming a left shoulder injury. Here we, based on the visual analysis of Sonny’s movements during the sixth round, show how a left shoulder’s rotator cuff tear cannot be the cause of the boxer failing to answer the bell for the seventh round. KEYWORDS: boxing; Muhammad Ali; World Heavyweight Championship; Miami Beach; rotator cuff injury The first fight between Sonny Liston and Cassius Clay took place on February 25, 1964 in Miami Beach. Liston failed to answer the bell for the seventh round and Clay was declared the winner by technical knockout (Remnick, 2000). The fight is one of the most controversial ever: it was the first time since 1919 that a World Heavyweight Champion had quit sitting on his stool. Liston said he had to quit because of a left shoulder injury (Tosches, 2000). However, there has been speculation since about whether the injury was severe enough to actually prevent him from continuing. It has been reported that Sonny Liston had been long suffering from shoulders’ bursitis and had been receiving cortisone shots, despite his notorious phobia for needles (Assael 2016). In training for the Clay fight, it has been reported that he re- injured his left shoulder and was in pain when striking the heavy bag. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen

Building a Champion: 1920 Akron Pros Ken Crippen BUILDING A CHAMPION: 1920 AKRON PROS By Ken Crippen It’s time to dig deep into the archives to talk about the first National Football League (NFL) champion. In fact, the 1920 Akron Pros were champions before the NFL was called the NFL. In 1920, the American Professional Football Association was formed and started play. Currently, fourteen teams are included in the league standings, but it is unclear as to how many were official members of the Association. Different from today’s game, the champion was not determined on the field, but during a vote at a league meeting. Championship games did not start until 1932. Also, there were no set schedules. Teams could extend their season in order to try and gain wins to influence voting the following spring. These late-season games were usually against lesser opponents in order to pad their win totals. To discuss the Akron Pros, we must first travel back to the century’s first decade. Starting in 1908 as the semi-pro Akron Indians, the team immediately took the city championship and stayed as consistently one of the best teams in the area. In 1912, “Peggy” Parratt was brought in to coach the team. George Watson “Peggy” Parratt was a three-time All-Ohio football player for Case Western University. While in college, he played professionally for the 1905 Shelby Blues under the name “Jimmy Murphy,” in order to preserve his amateur status. It only lasted a few weeks until local reporters discovered that it was Parratt on the field for the Blues. -

Boxing Edition

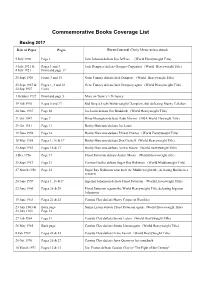

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Books Between Bites Program –

Books Between Bites Program 1987-2017 United Methodist Church, Batavia: 1987 – 2002 Batavia Public Library (Batavia, IL): beginning Sept. 2002 Lee C. Moorehead, Founder Becky Hoag & Betty Moorehead, Co-Directors Books & Reviewers/Presenters by Year Yes- if video available in Batavia Public Library YEAR DATE Video REVIEWER BOOK/author 1st Season – 1987-88 1987 Sept. 17 Jeff Schielke The Other Side of the Street by Barb and Sid Landfield Mayor of Batavia Historic Guide to Chicago and Its Suburbs By Ira Bach 1987 Oct. 15 Roberta Campbell Empire By Gore Vidal Historian & Columnist for the Chronicle 1987 Nov. 19 Dr. Edward Cave Horace’s Compromise, The Dilemma of the American High School By Batavia School Superintendent Theodore R. Sizer 1988 Jan. 14 Dr. Stephanie Marshall The Closing of the American Mind By Allan Bloom Director, IL Math & Science Academy 1988 Feb. 18 Dr. Mark E. Neely, Jr. Mary Todd Lincoln, A Biography By Jean Baker Resident Lincoln Scholar & Director, Lincoln Library & Museum, Ft. Wayne, IN 1988 March William J. Wood The Van Nortwick Geneology Edited by William B. Van Nortwick 17 Batavian Historian and former principal of JB. Nelson School 1988 April 21 Dr. Lee C. Moorehead Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Biography By Robert Moats Miller Minister of Programs, United Methodist Church, Batavia 1988 May 19 Dr. Seymour Halford The Naked Public Square By Richard John Neuhaus Senior Minister, United Methodist Church, Batavia 2nd Season – 1988-89 1988 Sept. 15 Jeff Schielke The Cycles of American History By Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Mayor of Batavia 1988 Oct. 20 Dr. Leon M. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Digital Media

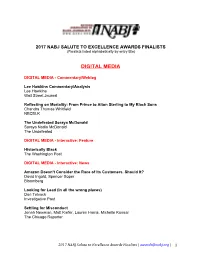

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952 -

Regulation of Bute and Lasix in New York State by Bennett Liebman

Regulation of Bute and Lasix in New York State By Bennett Liebman Government Attorney in Residence Albany Law School The horse racing community in the United States has been fighting over issues relating to phenylbutazone or butazolidin [hereinafter referred to as Bute] for more than 55 years and furosemide/salix [hereinafter referred to as Lasix] for more than 40 years. Over this period of time, the same questions have been asked by both supporters and opponents of administration of these drugs. The questions have been asked, but the questions have remained largely unanswered. After decades, the United States racing industry has been unable to come up with a clear consistent position on the proper utilization of these drugs. The purpose of this memorandum is to supply an overview for the members of the Gaming Commission of New York State’s involvement with drug testing issues and more specifically with the history of New York’s regulation of the two drugs most often associated with permissive medication: Bute and Lasix. Much of the focus of this memorandum is on thoroughbred racing, but it is important to understand that the analysis and the issues (and therefore the focus of the Commission) also must be applied to harness racing, which constitutes the vast majority of the pari-mutuel racing conducted in New York State. While some of the statements in this memorandum may be controversial, this memorandum is intended to be historical and not an advocacy piece. Historical New York Drug Testing Questions and Issues New York State, like most North American racing jurisdictions, uses the trainer responsibility rule.1 Under the New York version of this rule, a trainer is responsible for a drug positive unless the trainer is able to demonstrate by substantial evidence that he or she was not responsible for the administration of the drug.2 While New York State allows trainers to assert non- responsibility as an affirmative defense, other states have an even tougher version of the trainer responsibility rule. -

Hold Off Gas Disposal

Incumbents Win in Keansburg Election SEE STORY BELOW Cloudy, Mild Partly cloudy and mild with THEDMLY FINAL chance'of showers today and tonight. Sunny, warm tomor- Bed Bank, Freehold row. I Long Branch 7 EDITION (Sen Details, Pan 31 Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 226 RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 1969 \ 26 PAGES 10 CENTS illBIIIillillllllllB [J]!:.,;::;;:]!! in imrjijiitj!!;: j.jiiiiini .irjiiiiii. urji^iiN LJimiMiiiiJii.j-nNJii-j rju;Li;:/-UJii[iiiL;?.iiJt.:::;iJ.[ifj,iiii] riiLiiiiumdi Jiti!.[L[u::'Jt;m;ricii! HIM iiiirini U.S. Plans Park Complex, Including 4Hook' NEW YORK (AP) — A Lindsay, at a news confer- compassing 10 miles of gress. to some 10 million persons. reation Area, which will in- shore recreation area under An aide to Rep. James J. "Gateway National Recrea- ence on Breezy Point Beach shoreline, should be com- Most of the 15,600-acre site Lindsay estimated the cost clude Sandy Hook," said my bill," Case said. Howard, D-N.J., who had in- tion Area" will be built on in The Rockaways, said the pleted "in a couple of years." is owned by the public and of the park at $250 million. , Case in a statement yester- The Army is expected to troduced similar legislation both sides of New York Har- recreation area rules out a It would stretch from the will be tranferred to the fed- He said it would be develop- day. declare this summer it no in the House, said today the bor, the first such federal proposal by former City Rockaways diagonally across eral government by New ed and operated with federal Case has introduced a bill, longer needs all of its land congressman would like to project in an urban center.