Regulation of Bute and Lasix in New York State by Bennett Liebman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

138904 03 Dirtmile.Pdf

breeders’ cup dirt mile BREEDERs’ Cup DIRT MILE (GR. I) 7th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS AND UPWARD ONE MILE Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 123 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 120 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile will be limited to twelve (12). If more than twelve (12) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge Winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Alpha Godolphin Racing, LLC Lessee Kiaran P. McLaughlin B.c.4 Bernardini - Munnaya by Nijinsky II - Bred in Kentucky by Darley Broadway Empire Randy Howg, Bob Butz, Fouad El Kardy & Rick Running Rabbit Robertino Diodoro B.g.3 Empire Maker - Broadway Hoofer by Belong to Me - Bred in Kentucky by Mercedes Stables LLC Brujo de Olleros (BRZ) Team Valor International & Richard Santulli Richard C. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

250000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU

$250,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU (Grade III) 92nd Running – Saturday, May 7, 2016 (Kentucky Derby Day) 3-Year-Olds at One Mile on Dirt at Churchill Downs Stakes Record – 1:34.18, Competitive Edge (2015) Top Beyer Speed Figure – 112, Richter Scale (1997) Average Winning Beyer Speed Figure (since 1992) – 99.9 (2,398/24) Name Origin: Formerly known as the Derby Trial, the one-mile race for 3-year-olds was moved from Opening Night to Kentucky Derby Day and renamed the Pat Day Mile in 2015 to honor Churchill Downs’ all-time leading jockey Pat Day. Day, enshrined in the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame in 2005, won a record 2,482 races at Churchill Downs, including 156 stakes, from 1980-2005. None was more memorable than his triumph aboard W.C. Partee’s Lil E. Tee in the 1992 Kentucky Derby. He rode in a record 21 consecutive renewals of the Kentucky Derby, a streak that ended when hip surgery forced him to miss the 2005 “Run for the Roses.” Day’s Triple Crown résumé also included five wins in the Preakness Stakes – one short of Eddie Arcaro’s record – and three victories in the Belmont Stakes. His 8,803 career wins rank fourth all-time and his mounts that earned $297,914,839 rank second. During his career Day lead the nation in wins six times (1982-84, ’86, and ’90-91). His most prolific single day came on Sept. 13, 1989, when Day set a North American record by winning eight races from nine mounts at Arlington Park. -

Owners, Kentucky Derby (1875-2017)

OWNERS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2017) Most Wins Owner Derby Span Sts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Calumet Farm 1935-2017 25 8 4 1 Whirlaway (1941), Pensive (’44), Citation (’48), Ponder (’49), Hill Gail (’52), Iron Liege (’57), Tim Tam (’58) & Forward Pass (’68) Col. E.R. Bradley 1920-1945 28 4 4 1 Behave Yourself (1921), Bubbling Over (’26), Burgoo King (’32) & Brokers Tip (’33) Belair Stud 1930-1955 8 3 1 0 Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (’35) & Johnstown (’39) Bashford Manor Stable 1891-1912 11 2 2 1 Azra (1892) & Sir Huon (1906) Harry Payne Whitney 1915-1927 19 2 1 1 Regret (1915) & Whiskery (’27) Greentree Stable 1922-1981 19 2 2 1 Twenty Grand (1931) & Shut Out (’42) Mrs. John D. Hertz 1923-1943 3 2 0 0 Reigh Count (1928) & Count Fleet (’43) King Ranch 1941-1951 5 2 0 0 Assault (1946) & Middleground (’50) Darby Dan Farm 1963-1985 7 2 0 1 Chateaugay (1963) & Proud Clarion (’67) Meadow Stable 1950-1973 4 2 1 1 Riva Ridge (1972) & Secretariat (’73) Arthur B. Hancock III 1981-1999 6 2 2 0 Gato Del Sol (1982) & Sunday Silence (’89) William J. “Bill” Condren 1991-1995 4 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Joseph M. “Joe” Cornacchia 1991-1996 3 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Robert & Beverly Lewis 1995-2006 9 2 0 1 Silver Charm (1997) & Charismatic (’99) J. Paul Reddam 2003-2017 7 2 0 0 I’ll Have Another (2012) & Nyquist (’16) Most Starts Owner Derby Span Sts. -

Knights of Columbus

APR 18 E COVERS FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 3/15/18 2:16 PM Page 1 APRIL 2018 KNIGHTSOFCOLUMBUS April Columbia Ad ENGLISH.qxp_Layout 1 3/14/18 3:02 PM Page 1 Keeping Our Promise Find an agent at kofc.org or 1-800-345-5632 LIFE INSURANCE • DISABILITY INCOME INSURANCE • LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE • RETIREMENT ANNUITIES World’s Most Ethical Companies® and Ethisphere® names and marks are registered trademarks of Ethisphere LLC. APRIL 18 E 3_15 FINAL 2.qxp_Mar E 12 3/15/18 12:02 PM Page 1 KNIGHTSOFCOLUMBUS a P r i l 2 0 1 8 ♦ V o l u m E 9 8 ♦ N u m b E r 4 COLUMBIA FEATURES 8 Secretariat and the Knight Who Raced Him to Victory An interview with Ron Turcotte, the Hall of Fame jockey who rode the fastest steed of all time. BY ALTON J. PELOWSKI 14 Game On! The father of gold medal winner Amanda Pelkey reflects on watching his daughter’s dream come true. BY JOHN PELKEY, WITH COLUMBIA STAFF 16 The Last Martyr of Mexico The heroic witness of St. Pedro Maldonado, a member of the Knights, inspired the restoration of religious freedom to his state. BY JUAN GUAJARDO 20 ‘Love Is the Only Way’ An interview with actor Jim Caviezel about his role in the new film Paul, Apostle of Christ. BY COLUMBIA STAFF 22 Knighthood and the ‘New Man’ A rosary that belonged to St. Pedro de Jesús Maldonado Lucero, a Catholic men are called to be faithful servants, priest and Knight of Columbus who was martyred in 1937, is pic- protecting their families and building up the Church. -

Books Between Bites Program –

Books Between Bites Program 1987-2017 United Methodist Church, Batavia: 1987 – 2002 Batavia Public Library (Batavia, IL): beginning Sept. 2002 Lee C. Moorehead, Founder Becky Hoag & Betty Moorehead, Co-Directors Books & Reviewers/Presenters by Year Yes- if video available in Batavia Public Library YEAR DATE Video REVIEWER BOOK/author 1st Season – 1987-88 1987 Sept. 17 Jeff Schielke The Other Side of the Street by Barb and Sid Landfield Mayor of Batavia Historic Guide to Chicago and Its Suburbs By Ira Bach 1987 Oct. 15 Roberta Campbell Empire By Gore Vidal Historian & Columnist for the Chronicle 1987 Nov. 19 Dr. Edward Cave Horace’s Compromise, The Dilemma of the American High School By Batavia School Superintendent Theodore R. Sizer 1988 Jan. 14 Dr. Stephanie Marshall The Closing of the American Mind By Allan Bloom Director, IL Math & Science Academy 1988 Feb. 18 Dr. Mark E. Neely, Jr. Mary Todd Lincoln, A Biography By Jean Baker Resident Lincoln Scholar & Director, Lincoln Library & Museum, Ft. Wayne, IN 1988 March William J. Wood The Van Nortwick Geneology Edited by William B. Van Nortwick 17 Batavian Historian and former principal of JB. Nelson School 1988 April 21 Dr. Lee C. Moorehead Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Biography By Robert Moats Miller Minister of Programs, United Methodist Church, Batavia 1988 May 19 Dr. Seymour Halford The Naked Public Square By Richard John Neuhaus Senior Minister, United Methodist Church, Batavia 2nd Season – 1988-89 1988 Sept. 15 Jeff Schielke The Cycles of American History By Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Mayor of Batavia 1988 Oct. 20 Dr. Leon M. -

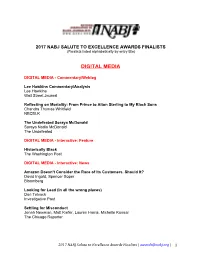

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

“Talk” on Albanian Territories (1392–1402)

Doctoral Dissertation A Model to Decode Venetian Senate Deliberations: Pregadi “Talk” on Albanian Territories (1392–1402) By: Grabiela Rojas Molina Supervisors: Gerhard Jaritz and Katalin Szende Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department Central European University, Budapest In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, Budapest, Hungary 2020 CEU eTD Collection To my parents CEU eTD Collection Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................. 1 List of Maps, Charts and Tables .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 A Survey of the Scholarship ........................................................................................................................... 8 a) The Myth of Venice ........................................................................................................................... 8 b) The Humanistic Outlook .................................................................................................................. 11 c) Chronicles, Histories and Diaries ..................................................................................................... 14 d) Albania as a Field of Study ............................................................................................................. -

Advancing Excellence

ADVANCING EXCELLENCE ADVANCING EXCELLENCE 2017 Advancing Excellence As the College of Media celebrates its 90th year, and the University of Illinois celebrates its 150th, we are reflecting on all of the accomplishments of our many distinguished alumni and the impact they have across the country and around the globe. The University of Illinois and the College of Media has much to be proud of, and as we look at the next 90 years, we know that our alumni and friends are at the center of what we will accomplish. We are thrilled to announce the public launch of to succeed, regardless of background or socioeconomic the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s status. We are confident that With Illinois will have a fundraising campaign “With Illinois,” and we are significant impact on our ability to fulfill this mission. excited about the impact the campaign will have on The exponential decreases in state funding for higher our campus, programs, students and faculty. With education in the past several years require us to rely Illinois is our most ambitious philanthropic campaign more heavily on private support to realize our mission. to date, and it will have transformative impact for Your support allows us to fulfill our commitment to generations to come. As we move forward with a tradition of excellence and we are grateful for your accomplishing the goals set forth by the campaign, partnership. we celebrate each of you who have already given so Please visit with.illinois.edu for more details regarding generously to the College of Media. Your investment the With Illinois campaign and media.illinois.edu/ in the college creates so many opportunities that would giving/withillinois for the College of Media’s campaign be out of reach for many of our students.