Chords with 1St and 4Th String Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

A Group-Theoretical Classification of Three-Tone and Four-Tone Harmonic Chords3

A GROUP-THEORETICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THREE-TONE AND FOUR-TONE HARMONIC CHORDS JASON K.C. POLAK Abstract. We classify three-tone and four-tone chords based on subgroups of the symmetric group acting on chords contained within a twelve-tone scale. The actions are inversion, major- minor duality, and augmented-diminished duality. These actions correspond to elements of symmetric groups, and also correspond directly to intuitive concepts in the harmony theory of music. We produce a graph of how these actions relate different seventh chords that suggests a concept of distance in the theory of harmony. Contents 1. Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 2. Three-tone harmonic chords 2 3. Four-tone harmonic chords 4 4. The chord graph 6 References 8 References 8 1. Introduction Early on in music theory we learn of the harmonic triads: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. Later on we find out about four-note chords such as seventh chords. We wish to describe a classification of these types of chords using the action of the finite symmetric groups. We represent notes by a number in the set Z/12 = {0, 1, 2,..., 10, 11}. Under this scheme, for example, 0 represents C, 1 represents C♯, 2 represents D, and so on. We consider only pitch classes modulo the octave. arXiv:2007.03134v1 [math.GR] 6 Jul 2020 We describe the sounding of simultaneous notes by an ordered increasing list of integers in Z/12 surrounded by parentheses. For example, a major second interval M2 would be repre- sented by (0, 2), and a major chord would be represented by (0, 4, 7). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

To View a Few Sample Pages of 30 Days to Better Jazz Guitar Comping

You will also find that you sometimes need to make big jumps across the neck to keep bass lines going. Keeping a solid bass line is more important than smooth voice leading. For example it’s more important to keep a bass line constantly going using simple chords rather than trying to find the hippest chords you know Day 24: Comping with Bass Lines After learning how to use a bass line with chords in the bossa nova, today’s lesson is about how to comp with bass lines in a more traditional jazz setting. Background on Comping with Bass Lines An essential comping technique that every guitarist learns at some point is to comp with bass lines. The two most important ingredients to this comping style are the feel and the bass line. As Joe Pass says “A good bass line must be able to stand by itself”, meaning that you add the chords where you can. Like many other subjects in this book, bass lines could fill up an entire book of their own, but this section will teach you the fundamental principles such as how to construct a bass line and apply it over the ii-V-I progression. What Chords Should I Use? As with bossa nova comping, it’s best to use simple voicings that are easy to grab to keep the bass line flowing as smoothly as possible. The chord diagram below shows the chords that are going to be used, notice that these are all simple inversions with no extensions, but they give the ear enough information to recognize the chord type and have roots on the bottom two strings. -

Arpeggios - Defined & Application an Arpeggio Is the Notes of a Chord Played Individually

Arpeggios - Defined & Application An arpeggio is the notes of a chord played individually. You can get creative with arpeggios and generate all kinds of unique sounds. Arpeggios can be utilized to outline chords, create melody lines, build riffs, add notes for color, and much more - the sky is the limit! KEY POINTS: There are a few key points to consider when playing arpeggios. The first is you want to hear the arpeggio one note at a time. You don’t want the arpeggio to sound like a strummed chord. You want to hear each note of the arpeggio individually. Arpeggios are the notes that make The goal is to infer the color of the chord with the arpeggio. Kill each note after it is played by muting the strings so the notes dont bleed into each up a chord. other. Another key to good arpeggio playing is mixing arpeggios together with scales, modes, and licks. Mix them into your lead lines as per the video lessons from this course. Try creating musical phrases combining Be sure to sound arpeggios with scales and licks. each note of the arpeggio Another key point is knowing where the arpeggios “live” within a scale. You want to be able to grab arpeggios quickly. Over utilizing the same individually. You three note triads up and down the neck can often sound a bit sterile and don’t want the non-melodic. So be sure to mix the arpeggio in with other scales and licks. arpeggio to sound Often when playing arpeggios you may need to utilize the same finger for like a strummed two or more adjacent strings. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Musical Chord Preference: Cultural Or Universal?

Working Paper Series MUSICAL CHORD PREFERENCE: CULTURAL OR UNIVERSAL? DATA FROM A NATIVE AMAZONIAN SOCIETY EDUARDO A. UNDURRAGA1,*, NICHOLAS Q. EMLEM2, MAXIMILIEN GUEZE3, DAN T. EISENBERG4, TOMAS HUANCA5, VICTORIA REYES-GARCÍA1,3, 6 VICTORIA RAZUMOVA7, KAREN GODOY8, TAPS BOLIVIA STUDY TEAM9, AND RICARDO GODOY3 1 Heller School, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02154, USA 2 Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 3 Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellatera, Barcelona, Spain 4 Department of Anthropology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA 5 Centro Boliviano de Investigación y Desarrollo Socio-integral (CBIDSI), Correo Central, San Borja, Beni, Bolivia 6 ICREA, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellatera, Barcelona, Spain 7 147 Sycamore St, Sommerville, MA 02145, USA 8 Pediatric Medical Care Inc., 1000 Broadway, Chelsea, MA 02150. USA 9 Tsimane’ Amazonian Panel Study, Correo Central, San Borja, Beni, Bolivia *To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] Word count: 9,372 (excluding abstract and cover page) 2 Abstract (338 words) Purpose. Recent evidence suggests that when listening to Western music, subjects cross- culturally experience similar emotions. However, we do not know whether cross-cultural regularities in affect response to music also emerge when listening to the building blocks of Western music, such as major and minor chords. In Western music, major chords are associated with happiness, a basic pan-human emotion, but the relation has not been tested in a remote non- Western setting. Here we address this question by measuring the relation between (i) listening to major and minor chords in major and minor keys and (ii) self-reported happiness in a remote society of native Amazonian hunters, gatherers, and farmers in Bolivia (Tsimane’). -

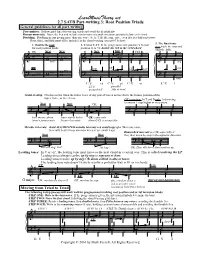

Root Position Triads Part-Writing

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.7 SATB Part-writing 3: Root Position Triads General guidelines for all part-writing Prerequisites. Follow guidelines for voicing triads and avoid the fiendish five. Roman numerals: Name the key and include roman numerals with inversion symbols below each chord. Doubling: Doubling means giving more than one voice (S, A, T, B) the same note, even if it is a different octave. Root, third, and fifth must all be included in the chord voicing (except #3 below). 3. The final tonic 1. Double the root 2. V-vi or V-VI: In the progression root position V to root may triple the root and for root position triads. position vi or VI, double the 3rd in the vi/VI chord. omit the fifth. OK NO! NO! NO! NO! YES 3rd! root root 5th! 3rd! 3rd LT! LT LT 3rd! root 5th! 3rd! root root C:V vi C:V vi C:V vi C:V I LT is parallel unresolved! 5ths & 8ves! Avoid overlap. Overlap occurs when the lower voice of any pair of voices moves above the former position of the upper voice, or vice-versa. OK exception: In T and B only, 3rd moving to unison 1 step higher or vice-versa NO! NO! OK bass moves above tenor moves below OK: same note tenor's former note former bass note (here C-C) is acceptable Melodic intervals: Avoid AUGMENTED melodic intervals and avoid leaps of a 7th in one voice. Generally best to keep common tones or use small leaps. Diminished intervals are OK, especially if NO! NO! they then move by step in the opposite direction.