Trichurida, Trichinellidae, Capillaria Hepatica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

F. Moravec: Trichinelloid Nematodes Parasitic in Cold-Blooded Vertebrates

FOLIA PARASITOLOGICA 49: 24, 2002 F. Moravec: Trichinelloid Nematodes Parasitic in Cold-blooded Vertebrates. Academia, Praha, 2001. ISBN 80-200-0805-5, hardback, 430 pp., 138 figs. Price CZK (Czech crowns) 395.00. The author of this monograph, Dr. František Moravec, their synonymy, description with illustrations, data on hosts, DrSc., of the Institute of Parasitology, Academy of Sciences locations, distribution and biology. The original comments on of the Czech Republic, České Budějovice (South Bohemia) is the nomenclature history, synonymy, morphological variabil- one of the world’s foremost authorities on parasitic nema- ity, differentiation and other aspects are indeed very valuable. todes, whose numerous classic papers and monographs on the In this way, the author assesses in detail 78 nematode species systematics and biology of this important parasite group are from fish, l5 from amphibians and 22 from reptiles. both well-known and internationally recognised. Consequently, the above conception, based on Moravec’s The content being assessed is devoted to morphology, (1982) originally modified classification system of capil- systematics, taxonomy and to other aspects of the parasite-host lariids, is used in the present book. The text of the book is relations within the large group of trichinelloid (mainly supplemented with a parasite-host list containing 347 fish, 47 capillariid) nematodes that parasitise cold-blooded animals on amphibian and 55 reptile species. The bibliography included a world-wide scale. The monograph contains detailed contains 669 citations of the literature sources. information on the methods of studying these parasites, their The monograph as a whole is of a high standard, much morphology, systematic value of individual features and on enhanced by good graphics and layout. -

Syn. Capillaria Plica) Infections in Dogs from Western Slovakia

©2020 Institute of Parasitology, SAS, Košice DOI 10.2478/helm20200021 HELMINTHOLOGIA, 57, 2: 158 – 162, 2020 Case Report First documented cases of Pearsonema plica (syn. Capillaria plica) infections in dogs from Western Slovakia P. KOMOROVÁ1,*, Z. KASIČOVÁ1, K. ZBOJANOVÁ2, A. KOČIŠOVÁ1 1University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice, Institute of Parasitology, Komenského 73, 041 81 Košice, Slovakia, *E-mail: [email protected]; 2Lapvet - Veterinary Clinic, Osuského 1630/44, 851 03 Bratislava, Slovakia Article info Summary Received November 12, 2019 Three clinical cases of dogs with Pearsonema plica infection were detected in the western part of Accepted February 20, 2020 Slovakia. All cases were detected within fi ve months. Infections were confi rmed after positive fi ndings of capillarid eggs in the urine sediment in following breeds. The eight years old Jack Russell Terrier, one year old Italian Greyhound, and eleven years old Yorkshire terrier were examined and treated. In one case, the infection was found accidentally in clinically healthy dog. Two other patients had nonspecifi c clinical signs such as apathy, inappetence, vomiting, polydipsia and frequent urination. This paper describes three individual cases, including the case history, clinical signs, examinations, and therapies. All data were obtained by attending veterinarian as well as by dog owners. Keywords: Urinary capillariasis; urine bladder; bladder worms; dogs Introduction prevalence in domestic dog population is unknown. The occur- rence of P. plica in domestic dogs was observed and described Urinary capillariasis caused by Pearsonema plica nematode of in quite a few case reports from Poland (Studzinska et al., 2015), family Capillariidae is often detected in wild canids. -

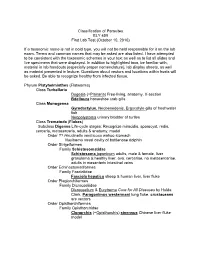

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus Idus

REVIEWS IN FISHERIES SCIENCE & AQUACULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2020.1822280 REVIEW Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus idus Mehis Rohtlaa,b, Lorenzo Vilizzic, Vladimır Kovacd, David Almeidae, Bernice Brewsterf, J. Robert Brittong, Łukasz Głowackic, Michael J. Godardh,i, Ruth Kirkf, Sarah Nienhuisj, Karin H. Olssonh,k, Jan Simonsenl, Michał E. Skora m, Saulius Stakenas_ n, Ali Serhan Tarkanc,o, Nildeniz Topo, Hugo Verreyckenp, Grzegorz ZieRbac, and Gordon H. Coppc,h,q aEstonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; bInstitute of Marine Research, Austevoll Research Station, Storebø, Norway; cDepartment of Ecology and Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Łod z, Poland; dDepartment of Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia; eDepartment of Basic Medical Sciences, USP-CEU University, Madrid, Spain; fMolecular Parasitology Laboratory, School of Life Sciences, Pharmacy and Chemistry, Kingston University, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK; gDepartment of Life and Environmental Sciences, Bournemouth University, Dorset, UK; hCentre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft, Suffolk, UK; iAECOM, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada; jOntario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada; kDepartment of Zoology, Tel Aviv University and Inter-University Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, Tel Aviv, -

From Skin of Red Snapper, Lutjanus Campechanus (Perciformes: Lutjanidae), on the Texas–Louisiana Shelf, Northern Gulf of Mexico

J. Parasitol., 99(2), 2013, pp. 318–326 Ó American Society of Parasitologists 2013 A NEW SPECIES OF TRICHOSOMOIDIDAE (NEMATODA) FROM SKIN OF RED SNAPPER, LUTJANUS CAMPECHANUS (PERCIFORMES: LUTJANIDAE), ON THE TEXAS–LOUISIANA SHELF, NORTHERN GULF OF MEXICO Carlos F. Ruiz, Candis L. Ray, Melissa Cook*, Mark A. Grace*, and Stephen A. Bullard Aquatic Parasitology Laboratory, Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures, College of Agriculture, Auburn University, 203 Swingle Hall, Auburn, Alabama 36849. Correspondence should be sent to: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Eggs and larvae of Huffmanela oleumimica n. sp. infect red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus (Poey, 1860), were collected from the Texas–Louisiana Shelf (28816036.5800 N, 93803051.0800 W) and are herein described using light and scanning electron microscopy. Eggs in skin comprised fields (1–5 3 1–12 mm; 250 eggs/mm2) of variously oriented eggs deposited in dense patches or in scribble-like tracks. Eggs had clear (larvae indistinct, principally vitelline material), amber (developing larvae present) or brown (fully developed larvae present; little, or no, vitelline material) shells and measured 46–54 lm(x¼50; SD 6 1.6; n¼213) long, 23–33 (27 6 1.4; 213) wide, 2–3 (3 6 0.5; 213) in eggshell thickness, 18–25 (21 6 1.1; 213) in vitelline mass width, and 36–42 (39 6 1.1; 213) in vitelline mass length with protruding polar plugs 5–9 (7 6 0.6; 213) long and 5–8 (6 6 0.5; 213) wide. Fully developed larvae were 160–201 (176 6 7.9) long and 7–8 (7 6 0.5) wide, had transverse cuticular ridges, and were emerging from some eggs within and beneath epidermis. -

ECVP/ESVP Summer School in Veterinary Pathology Summer School 2014 – Mock Exam

ECVP/ESVP Summer School in Veterinary Pathology Summer School 2014 – Mock Exam CASE 6 Prairie dog liver capillariasis eggs and adults Histologic Description Points Style 0,5 Approximately 60%(0,5) of liver parenchyma is expanded to substituted by multifocal to 2 coalescing multinodular (0,5) inflammation (0,5) and necrosis (0,5) associated with parasite eggs and adults Multi nodular inflammation association with EGG DESCRIPTION Oval 70x40 microns 0,5 Two polar plugs Bioperculated eggs 1 Thick anisotropic shell 3-4 micron thick 1 Interpretation as Capillaria 1 Inflammatory cells associated with or surrounding eggs 0 Prevalence of reactive macrophages and multinucleated giant cells 1 Followed by mature lymphocytes and plasmacells 1 Lesser numbers of Neutrophils 0,5 Eosinophils 0,5 Peripheral deposition of collagen (fibrosis) 1 Peripheral hepatocytes with distinct cell borders and intensenly eosinophilic 1 cytoplasm (0,5) (coagulative necrosis) 0,5 Atrophy of adjacent hepatocytes 1 ADULT DESCRIPTION 0 Transversal sections of organisms with digestive (0,5) and reproductive tracts (0,5) 2 characterized by coelomyarian/polymyarian musculature (0,5) interpreted as adult nematodes 0, 5 Nematode excrements 0,5 Necrosis of hepatocytes adjacent to adults (parasite migration/tracts) 0,5 Lymphocytes and plasmacells surrounding adults Hemorrhages/hyperhaemia 0,5 Hepatic microvesicular lipidosis 0,5 Biliary hyperplasia 0,5 Morphologic Diagnosis Severe (0,5), multifocal to locally extensive (0,5), subacute to 3 chronic (0,5), necrotizing (0,5) and granulomatous (0,5) and eosinophilic (0,5) hepatitis with intralesional Capillaria eggs and adults Etiology Capillaria hepatica 2 20 ECVP/ESVP Summer School in Veterinary Pathology Summer School 2014 – Mock Exam HD: Approximately 60-70 % of liver parenchyma, is effaced by large, multifocal to coalescing, poorly demarcated nodules. -

Wildlife Parasitology in Australia: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Zoology, 2018, 66, 286–305 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO19017 Wildlife parasitology in Australia: past, present and future David M. Spratt A,C and Ian Beveridge B AAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BVeterinary Clinical Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Werribee, Vic. 3030, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Wildlife parasitology is a highly diverse area of research encompassing many fields including taxonomy, ecology, pathology and epidemiology, and with participants from extremely disparate scientific fields. In addition, the organisms studied are highly dissimilar, ranging from platyhelminths, nematodes and acanthocephalans to insects, arachnids, crustaceans and protists. This review of the parasites of wildlife in Australia highlights the advances made to date, focussing on the work, interests and major findings of researchers over the years and identifies current significant gaps that exist in our understanding. The review is divided into three sections covering protist, helminth and arthropod parasites. The challenge to document the diversity of parasites in Australia continues at a traditional level but the advent of molecular methods has heightened the significance of this issue. Modern methods are providing an avenue for major advances in documenting and restructuring the phylogeny of protistan parasites in particular, while facilitating the recognition of species complexes in helminth taxa previously defined by traditional morphological methods. The life cycles, ecology and general biology of most parasites of wildlife in Australia are extremely poorly understood. While the phylogenetic origins of the Australian vertebrate fauna are complex, so too are the likely origins of their parasites, which do not necessarily mirror those of their hosts. -

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C. BEAVER, Ph.D. AMONG ANIMALS in general there is a In the development of our concepts of larva II. wide variety of parasitic infections in migrans there have been four major steps. The which larval stages migrate through and some¬ first, of course, was the discovery by Kirby- times later reside in the tissues of the host with¬ Smith and his associates some 30 years ago of out developing into fully mature adults. When nematode larvae in the skin of patients with such parasites are found in human hosts, the creeping eruption in Jacksonville, Fla. (6). infection may be referred to as larva migrans This was followed immediately by experi¬ although definition of this term is becoming mental proof by numerous workers that the increasingly difficult. The organisms impli¬ larvae of A. braziliense readily penetrate the cated in infections of this type include certain human skin and produce severe, typical creep¬ species of arthropods, flatworms, and nema¬ ing eruption. todes, but more especially the nematodes. From a practical point of view these demon¬ As generally used, the term larva migrans strations were perhaps too conclusive in that refers particularly to the migration of dog and they encouraged the impression that A. brazil¬ cat hookworm larvae in the human skin (cu¬ iense was the only cause of creeping eruption, taneous larva migrans or creeping eruption) and detracted from equally conclusive demon¬ and the migration of dog and cat ascarids in strations that other species of nematode larvae the viscera (visceral larva migrans). In a still have the ability to produce similarly the pro¬ more restricted sense, the terms cutaneous larva gressive linear lesions characteristic of creep¬ migrans and visceral larva migrans are some¬ ing eruption. -

A Study of the Nematode Capillaria Boehm!

A STUDY OF THE NEMATODE CAPILLARIA BOEHM! (SUPPERER, 1953): A PARASITE IN THE NASAL PASSAGES OF THE DOG By CAROLEE. MUCHMORE Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1982 Master of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1986 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1998 1ht>I~ l qq ~ 1) t-11 q lf). $ COPYRIGHT By Carole E. Muchmore May, 1998 A STUDY OF THE NEMATODE CAPILLARIA BOEHM!. (SUPPERER, 1953): APARASITE IN THE NASAL PASSAGES OF THE DOG Thesis Appro~ed: - cl ~v .L-. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My first and most grateful thanks go to Dr. Helen Jordan, my major adviser, without whose encouragement and vision this study would never have been completed. Dr. Jordan is an exceptional individual, a dedicated parasitologist, indefatigable and with limitless integrity. Additional committee members to whom I owe many thanks are Dr. Carl Fox, Dr. John Homer, Dr. Ulrich Melcher, Dr. Charlie Russell. - Dr. Fox for assistance in photographing specimens. - Dr. Homer for his realistic outlook and down-to-earth common sense approach. - Dr. Melcher for his willingness to help in the intricate world of DNA technology. - Dr. Charlie Russell, recruited from plant nematology, for fresh perspectives. Thanks go to Dr. Robert Fulton, department head, for his gracious support; Dr. Sidney Ewing who was always able to provide the final word on scientific correctness; Dr. Alan Kocan for his help in locating and obtaining specimens. Special appreciation is in order for Dr. Roger Panciera for his help with pathology examinations, slide preparation and camera operation and to Sandi Mullins for egg counts and helping collect capillarids from the greyhounds following necropsy. -

Trichinella Nativa in a Black Bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2005 Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, [email protected] H.R. Gamble National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.S. Zarlenga Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory & Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory C. Cross Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory J. Finnigan New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Hill, D.E.; Gamble, H.R.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Cross, C.; and Finnigan, J., "Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire" (2005). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 2244. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/2244 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Veterinary Parasitology 132 (2005) 143–146 www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill a,*, H.R. Gamble c, D.S. Zarlenga a,b, C. Coss a, J. Finnigan d a United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Animal and Natural Resources Institute, Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA b Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA c National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, USA d The Food Safety Microbiology Unit, New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord, NH, USA Abstract A suspected case of trichinellosis was identified in a single patient by the New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories in Concord, NH. -

Trichinella Britovi

Pozio et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:520 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04394-7 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Diferences in larval survival and IgG response patterns in long-lasting infections by Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi and Trichinella pseudospiralis in pigs Edoardo Pozio1, Giuseppe Merialdi2, Elio Licata3, Giacinto Della Casa4, Massimo Fabiani1, Marco Amati1, Simona Cherchi1, Mattia Ramini2, Valerio Faeti4, Maria Interisano1, Alessandra Ludovisi1, Gianluca Rugna2, Gianluca Marucci1, Daniele Tonanzi1 and Maria Angeles Gómez‑Morales1* Abstract Background: Domesticated and wild swine play an important role as reservoir hosts of Trichinella spp. and a source of infection for humans. Little is known about the survival of Trichinella larvae in muscles and the duration of anti‑ Trichinella antibodies in pigs with long‑lasting infections. Methods: Sixty pigs were divided into three groups of 20 animals and infected with 10,000 larvae of Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi or Trichinella pseudospiralis. Four pigs from each group were sacrifced at 2, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post‑infection (p.i.) and the number of larvae per gram (LPG) of muscles was calculated. Serum samples were tested by ELISA and western blot using excretory/secretory (ES) and crude antigens. Results: Trichinella spiralis showed the highest infectivity and immunogenicity in pigs and larvae survived in pig mus‑ cles for up to 2 years p.i. In these pigs, the IgG level signifcantly increased at 30 days p.i. and reached a peak at about 60 days p.i., remaining stable until the end of the experiment. In T. britovi-infected pigs, LPG was about 70 times lower than for T.