Renew, Elevate, Modernize a Blueprint for a 21St-Century U.S.-ROK Alliance Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6/06 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising

8/1/2020 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising By Georgy Katsiaficas Abstract Drawing from US Embassy documents, World Bank statistics, and memoirs of former US Ambassador Gleysteen and Commanding General Wickham, US actions during Chun Doo Hwan’s first months in power are examined. The Embassy’s chief concern in this period was liberalization of the Korean economy and securing US bankers’ continuing investments. Political liberalization was rejected as an appropriate goal, thereby strengthening Korean anti-Americanism. The timing of economic reforms and US support for Chun indicate that the suppression of the Gwangju Uprising made possible the rapid imposition of the neoliberal accumulation regime in the ROK. With the long-term success of increasing American returns on investments, serious strains are placed on the US/ROK alliance. South Korean Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism in South Korea remains a significant problem, one that simply won’t disappear. As late as 1980, the vast majority of South Koreans believed the United States was a great friend and would help them achieve democracy. During the Gwangju Uprising, the point of genesis of contemporary anti-Americanism, a rumor that was widely believed had the aircraft carrier USS Coal Sea entering Korean waters to aid the insurgents against Chun Doo Hwan and the new military dictatorship. Once it became apparent that the US had supported Chun and encouraged the new military authorities to suppress the uprising (even requesting that they delay the re-entry of troops into the city until after the Coral Sea had arrived), anti-Americanism in South Korea emerged with startling rapidity and unexpected longevity. -

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

108–289 Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2004

S. HRG. 108–289 FOREIGN OPERATIONS, EXPORT FINANCING, AND RELATED PROGRAMS APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2800/S. 1426 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR FOREIGN OPERATIONS, EXPORT FINANCING, AND RELATED PROGRAMS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR END- ING SEPTEMBER 30, 2004, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Agency for International Development Department of State Nondepartmental Witnesses Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 85–923 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky TOM HARKIN, Iowa CONRAD BURNS, Montana BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HARRY REID, Nevada JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HERB KOHL, Wisconsin ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah PATTY MURRAY, Washington BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JAMES W. MORHARD, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director TERRENCE E. -

U.S.-South Korea Relations

U.S.-South Korea Relations Mark E. Manyin, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs Mary Beth D. Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation Brock R. Williams Analyst in International Trade and Finance Jonathan R. Corrado Research Associate May 23, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41481 U.S.-South Korea Relations Summary Overview South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea, or ROK) is one of the United States’ most important strategic and economic partners in Asia. Congressional interest in South Korea is driven by both security and trade interests. Since the early 1950s, the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty commits the United States to help South Korea defend itself. Approximately 28,500 U.S. troops are based in the ROK, which is included under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella.” Washington and Seoul cooperate in addressing the challenges posed by North Korea. The two countries’ economies are joined by the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). South Korea is the United States’ seventh-largest trading partner and the United States is South Korea’s second- largest trading partner. Between 2009 and the end of 2016, relations between the two countries arguably reached their most robust state in decades. Political changes in both countries in 2017, however, have generated uncertainty about the state of the relationship. Coordination of North Korea Policy Dealing with North Korea is the dominant strategic concern of the relationship. The Trump Administration appears to have raised North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs to a top U.S. -

Threading the Needle Proposals for U.S

“Few actions could have a more important impact on U.S.-China relations than returning to the spirit of the U.S.-China Joint Communique of August 17, 1982, signed by our countries’ leaders. This EastWest Institute policy study is a bold and pathbreaking effort to demystify the issue of arms sales to Taiwan, including the important conclusion that neither nation is adhering to its commitment, though both can offer reasons for their actions and views. That is the first step that should lead to honest dialogue and practical steps the United States and China could take to improve this essential relationship.” – George Shultz, former U.S. Secretary of State “This EastWest Institute report represents a significant and bold reframing of an important and long- standing issue. The authors advance the unconventional idea that it is possible to adhere to existing U.S. law and policy, respect China’s legitimate concerns, and stand up appropriately for Taiwan—all at the same time. I believe EWI has, in fact, ‘threaded the needle’ on an exceedingly challenging policy problem and identified a highly promising solution-set in the sensible center: a modest voluntary capping of annual U.S. arms deliveries to Taiwan relative to historical levels concurrent to a modest, but not inconsequential Chinese reduction of its force posture vis-à-vis Taiwan. This study merits serious high-level attention.” – General (ret.) James L. Jones, former U.S. National Security Advisor “I commend co-authors Piin-Fen Kok and David Firestein for taking on, with such skill and methodological rigor, a difficult issue at the core of U.S-China relations: U.S. -

The Future of Northeast Asia and the Korea-US Alliance

Joint Report released in June 2021 Special Conference on The Future of Northeast Asia and the Korea-U.S. Alliance CO-CHAIRS Joseph Nye, John Hamre, Victor Cha Park In-kook, Yoon Young-kwan, Kim Sung-han Table of Contents Executive Summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 07 This Joint Report is an outcome of the activities carried out by the CHEY-CSIS Commission on Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula (hereinafter referred as the Commission). The Policy Recommendations ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Commission consists of a high-level delegation of former government officials and scholars from the U.S. and ROK. It identifies the unprecedented geostrategic uncertainties and Geopolitics in Northeast Asia ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 challenges generated by shifts in the balance of power, intensifying Sino-American competition, technological innovation, debilitating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and growing North Korea ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 income disparities. Against this backdrop, the Commission aims to explore the geopolitical implications in the Northeast Asian region and the Korean Peninsula, including the ROK- ROK-U.S. Alliance ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

The Asan Plenum 2018, “Illiberal International Order”

Embargoed for release at 0600 Monday, April 16, 2018 The Asan Plenum 2018, “Illiberal International Order” 82-2-3701-7377 [email protected] SEOUL, April 9, 2018 – The Asan Institute for Policy Studies (http://en.asaninst.org/) will host the Asan Plenum 2018 on April 24 (Tue.) – 25 (Wed.) at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Hannam-dong, Seoul. The title of this year’s Plenum is “Illiberal International Order.” Edwin Fuelner, Founder of The Heritage Foundation, will deliver the keynote address. The Plenum will bring together over 100 distinguished experts, policymakers, scholars, and members of the media including: • Paul Wolfowitz, Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense and President of the World Bank • James Steinberg, Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State • Karel De Gucht, Former Minister of Foreign Affairs for Belgium • Funabashi Yoichi, Editor-in-Chief, Asahi Shimbun • Daniel Russel, Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs • Victor Cha, Senior Adviser and Korea Chair, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) • Wang Dong, Professor, Peking University School of International Studies • Hugh White, Professor, Australia National University This year’s Plenum addresses the myriad challenges threatening the liberal international order (LIO) today. In the U.S. and Britain, the rise of populism has called into question the West’s commitment to uphold the rules-based global order. Nondemocratic regimes in China and Russia are rewriting these rules and undermining the institutions that have sustained them. Outliers, such as North Korea and Iran, are stoking regional tensions, while transnational issues including terrorism, cyber security, and geoeconomics continue to test the viability and endurance of the LIO. -

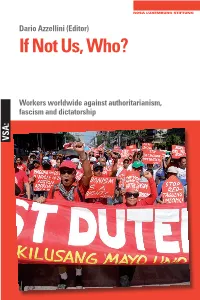

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

The GW Undergraduate Review, Volume 4

41 KEYWORDS: Korean democracy, Gwangju Uprising, art censorship DOI: https://doi.org/10.4079/2578-9201.4(2021).08 The Past and Present of Cultural Censorship in South Korea: Minjung Art During and After the Gwangju Uprising VIVIAN KONG INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, ESIA ‘23, [email protected] ABSTRACT The Gwangju Uprising provided pivotal momentum for South Korea’s path toward democracy and was assisted by the artwork by Minjung artists. However, the state’s continuous censorship of democratic art ironically contradicts with the principles that Gwangju upholds, generating the question: how does the censorship of democratic artists during and after the Gwangju Democratic Uprising affect artistic political engagement and reflect upon South Korea’s democracy? I argue that censorship of Minjung art is hypocritical in nature by providing key characteristics of democracy the South Korean state fails to meet. Minjung art intends to push for political change and has roots in the Gwangju Uprising, an event that was the catalyst in creating a democratic state, yet the state continues to suppress a democratic freedom of expression. Looking to dissolve the line between activism and art, Korean Minjung artists have been producing content criticizing the state from the 1980s to modern day despite repression from the state. Past studies and first-person accounts on Gwangju have focused separately on authoritarian censorship on art or on modern cultural censorship. This paper seeks to bridge this gap and identify the parallels between artistic censorship during South Korea’s dictatorships and during its democracy to identify the hypocrisy of the state regarding art production and censorship. -

Global Value Chains in an Era of Strategic Uncertainty: Prospects for Us–Rok Cooperation

GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS IN AN ERA OF STRATEGIC UNCERTAINTY: PROSPECTS FOR US–ROK COOPERATION GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS IN AN ERA OF STRATEGIC UNCERTAINTY: PROSPECTS FOR US-ROK COOPERATION Dr. Miyeon Oh Dr. Robert Dohner Dr. Trey Herr I ATLANTIC COUNCIL Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. The Scowcroft Center’s Asia Security Initiative promotes forward-looking strategies and constructive solutions for the most pressing issues affecting the Indo-Pacific region, particularly the rise of China, in order to enhance cooperation between the United States and its regional allies and partners. The mission of ASI is help the United States better work with Asian allies and partners in responding to the rise of China. Its mission is also to translate US policy objectives and strategic aims into nuanced messages to Asian stakeholders that incorporate Indo-Pacific voices in order to foster a community of like-minded nations committed to adapting and defending the rules-based international system. In service of these efforts, ASI leverages its mission, method, and talent to provide purposeful programming to address traditional strategic issues in the Indo-Pacific while also developing insight into emerging challenges in non-traditional areas such as global supply chains, changing trade architecture, infrastructure development, energy security, digital connectivity, and advanced technologies that are increasingly impacting the realm of national security. -

Truth and Reconciliation� � Activities of the Past Three Years�� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

Truth and Reconciliation Activities of the Past Three Years CONTENTS President's Greeting I. Historical Background of Korea's Past Settlement II. Introduction to the Commission 1. Outline: Objective of the Commission 2. Organization and Budget 3. Introduction to Commissioners and Staff 4. Composition and Operation III. Procedure for Investigation 1. Procedure of Petition and Method of Application 2. Investigation and Determination of Truth-Finding 3. Present Status of Investigation 4. Measures for Recommendation and Reconciliation IV. Extra-Investigation Activities 1. Exhumation Work 2. Complementary Activities of Investigation V. Analysis of Verified Cases 1. National Independence and the History of Overseas Koreans 2. Massacres by Groups which Opposed the Legitimacy of the Republic of Korea 3. Massacres 4. Human Rights Abuses VI. MaJor Achievements and Further Agendas 1. Major Achievements 2. Further Agendas Appendices 1. Outline and Full Text of the Framework Act Clearing up Past Incidents 2. Frequently Asked Questions about the Commission 3. Primary Media Coverage on the Commission's Activities 4. Web Sites of Other Truth Commissions: Home and Abroad President's Greeting In entering the third year of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea (the Commission) is proud to present the "Activities of the Past Three Years" and is thankful for all of the continued support. The Commission, launched in December 2005, has strived to reveal the truth behind massacres during the Korean War, human rights abuses during the authoritarian rule, the anti-Japanese independence movement, and the history of overseas Koreans. It is not an easy task to seek the truth in past cases where the facts have been hidden and distorted for decades. -

The Looming Taiwan Fighter Gap

This Page Intentionally Left Blank The Looming Taiwan Fighter Gap US-Taiwan Business Council October 1, 2012 This report was published in October 2012 by the US-Taiwan Business Council. The Council is a non-profit, member-based organization dedicated to developing the trade and business relationship between the United States and Taiwan. Members consist of public and private companies with business interests in Taiwan. This report serves as one way for the Council to offer analysis and information in support of our members’ business activities in the Taiwan market. The publication of this report is part of the overall activities and programs of the Council, as endorsed by its Board of Directors. However, the views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of individual members of the Board of Directors or Executive Committee. 2012 US-Taiwan Business Council The US-Taiwan Business Council has the sole and exclusive rights to the copyrighted material contained in this report. Use of any material contained in this report for any purpose that is not expressly authorized by the US-Taiwan Business Council, or duplicating any or part of the material for any purpose whatsoever, without the prior written consent of the US-Taiwan Business Council, is strictly prohibited and unlawful. 1700 North Moore Street, Suite 1703 Arlington, Virginia 22209 Phone: (703) 465-2930 Fax: (703) 465-2937 [email protected] www.us-taiwan.org Edited by Lotta Danielsson Printed in the United States The Looming Taiwan Fighter Gap TABLE OF CONTENTS