Too White to Be Regarded As Aborigines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Looking for the Ducks Nuts There's More to Life

STOP LOOKING FOR THE DUCKS NUTS THERE'S MORE TO LIFE. get a fresh perspective on living. Kimberley loop TRIP NOTES JUN E 28 - JULY 15, 2021 E G R A H C e r THE HADAGUTFUL DIFFERENCE Remote Australian destinations are our idea of ‘getting away'. If you share that same dream, let us make it happen. Our aim is to provide as much freedom as you, our ‘fellow adventurers’, need to come back feeling refreshed and rejuvenated... call it ‘Real Life Expedition Therapy’. Hadagutful Expeditions provide personally guided off-road Australian adventures. With Hadagutful you will venture to extraordinary and idyllic Australian locations. We specialise in 5-18 day Overland Expeditions exclusively for just one, two or three guests. Hadagutful provides all equipment, catering and planning to ensure that your Expedition travels are truly extraordinary. Hadagutful is different from other tour operators. Our Expedition travel is a ‘hands-on’ experience. You will get involved with camp set-up, building fires, and daily adventures. Choose to stay a little longer and not be on the go all the time. The Expedition will feel like it’s your ‘own’, allowing you to have input into where you go and what we do. AFTER ALL, HAVEN'T YOU HADGUTFUL? © Hadagutful Overland Expeditions l Kimberley Loop 2021 l www.hadagutful.com.au | There’s More To Life E G R A H C e r kimberley loop EXPEDITION SUMMARY This is the Holy Grail, the Gold Medal, the Ducks Nuts of expeditions. 18 days along the famous Gibb River Road and through the Kimberley, starting and finishing in Broome. -

Drysdale River National Park # 2: June 24 - July 8, 2007

Drysdale River National Park # 2: June 24 - July 8, 2007 Update 29 April 2007 Drysdale River National Park is the largest and least accessible in the Kimberley. There is no public road leading to it. There is no airstrip inside it. On previous trips, we have gone to the park via the 4WD track that passes over the Aboriginal owned Carson River Station. In July 2004, we were informed that the Aboriginal community at Kalumburu had decided to close this access. We have been told that it is open again and hope that it remains open for this trip This inaccessibility is the key to one of the park's main attractions — few introduced pests and an ecology that remains relatively undisturbed in comparison to much of the rest of Australia. The park is a paradise for birdwatchers. It is usually easy to spot freshwater crocodiles in the pools below Solea Falls. Fishing is excellent, at its best below the falls. It’s a bush paradise. Getting there is the problem. We had planned to use float planes to go into the park. Sadly, Alligator Airways did not have enough work for their float planes so they disposed of all but one and can no longer offer this service. At this point we plan to drive in via Carson River for the start of the Drysdale No. 1 trip – assuming that we can get the same permission that a private group has got. Those doing only this trip will fly in by helicopter and light aircraft and drive out in the vehicles we left at the start four weeks earlier. -

Fish Fauna of the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia - Including the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri Aboriginal Names

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.22(2).2004.147-161 Records of the Westelll Allstralllll1 A//uselllll 22 ]47-]6] (2004). Fish fauna of the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley region of Western Australia - including the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri Aboriginal names J J 2 3 David L. Morgan , Mark G. Allen , Patsy Bedford and Mark Horstman 1 Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research, School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6]50 KImberley Language Resource Centre, PO Box 86, Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia 6765 'Kimberley Land Council, PO Box 2145, Broome Western Australia 6725 Abstract - This project surveyed the fish fauna of the Fitzroy River, one of Australia's largest river systems that remains unregulated, 'located in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. A total of 37 fish species were recorded in the 70 sites sampled. Twenty-three of these species are freshwater fishes (i.e. they complete their life-cycle in freshwater), the remainder being of estuarine or marine origin that may spend part of their life-cycle in freshwater. The number of freshwater species in the Fitzroy River is high by Australian standards. Three of the freshwater fish species recorded ar'e currently undescribed, and two have no formal common or scientific names, but do have Aboriginal names. Where possible, the English (common), scientific and Aboriginal names for the different speCIes of the river are given. This includes the Aboriginal names of the fish for the following five languages (Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri) of the Fitzroy River Valley. The fish fauna of the river was shown to be significantly different between each of the lower, middle and upper reaches of the main channeL Furthermore, the smaller tributaries and the upper gorge country sites were significantly different to those in the main channel, while the major billabongs of the river had fish assemblages significantly different to all sites with the exception of the middle reaches of the river. -

Catholic Missions to Aboriginal Australia: an Evaluation of Their Overall Effect

Catholic missions to Aboriginal Australia: an evaluation of their overall effect James Franklin* Abstract The paper gives an overview of the Catholic Church’s missionary efforts to the Aborigines of northern and western Australia up to 1970. It aims to understand the interaction of missions with native culture and the resulting hybrid culture created on the missions. It describes the differing points of view of missionaries and the generations who grew up on the missions. It is argued that the culture created on the missions by the joint efforts of missionaries and local peoples was by and large a positive phase in Australian black history, between the violence of pre-contact times and the dysfunctionality of recent decades. Criticisms of the missions are addressed, such as those arising from their opposition to aspects of native culture and from their involvement in child removals. Introduction There is no overview available of the Catholic mission effort to Aboriginal Australia (or of the Christian missions overall). A short article cannot fill that gap, but can make a start by indicating the topics that need to be covered, the questions to be answered and the sources available. Here, “missions” is taken in the traditional sense, where a group of white clergy and helpers establish themselves in a remote location and preach and provide other services to local black people who have had little contact with whites. Such initiatives as apostolates to urban black communities are excluded. The topic is important because the history of Aboriginal interaction with missions is quite different from the history of other white-black interactions in Australia, and because many present-day remote communities are former missions which still have strong connections with their mission past. -

Fishes of the King Edward and Carson Rivers with Their Belaa and Ngarinyin Names

Fishes of the King Edward and Carson Rivers with their Belaa and Ngarinyin names By David Morgan, Dolores Cheinmora Agnes Charles, Pansy Nulgit & Kimberley Language Resource Centre Freshwater Fish Group CENTRE FOR FISH & FISHERIES RESEARCH Kimberley Language Resource Centre Milyengki Carson Pool Dolores Cheinmora: Nyarrinjali, kaawi-lawu yarn’ nyerreingkana, Milyengki-ngûndalu. Waj’ nyerreingkana, kaawi-ku, kawii amûrike omûrung, yilarra a-mûrike omûrung. Agnes Charles: We are here at Milyengki looking for fish. He got one barramundi, a small one. Yilarra is the barramundi’s name. Dolores Cheinmora: Wardi-di kala’ angbûnkû naa? Agnes Charles: Can you see the fish, what sort of fish is that? Dolores Cheinmora: Anja kûkûridingei, Kalamburru-ngûndalu. Agnes Charles: This fish, the Barred Grunter, lives in the Kalumburu area. Title: Fishes of the King Edward and Carson Rivers with their Belaa and Ngarinyin names Authors: D. Morgan1 D. Cheinmora2, A. Charles2, Pansy Nulgit3 & Kimberley Language Resource Centre4 1Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research, Murdoch University, South St Murdoch WA 6150 2Kalumburu Aboriginal Corporation 3Kupungari Aboriginal Corporation 4Siobhan Casson, Margaret Sefton, Patsy Bedford, June Oscar, Vicki Butters - Kimberley Language Resource Centre, Halls Creek, PMB 11, Halls Creek WA 6770 Project funded by: Land & Water Australia Photographs on front cover: Lower King Edward River Long-nose Grunter (inset). July 2006 Land & Water Australia Project No. UMU22 Fishes of the King Edward River - Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research, Murdoch University / Kimberley Language Resource Centre 2 Acknowledgements Most importantly we would like to thank the people of the Kimberley, particularly the Traditional Owners at Kalumburu and Prap Prap. This project would not have been possible without the financial support of Land & Water Australia. -

Kimberley Wilderness Adventures Embark on a Truly Inspiring Adventure Across Australia’S Last Frontier with APT

Kimberley Wilderness Adventures Embark on a truly inspiring adventure across Australia’s last frontier with APT. See the famous beehive domes of the World Heritage-listed Bungle Bungle range in Purnululu National Park 84 GETTING YOU THERE FROM THE UK 99 Flights to Australia are excluded from the tour price in this section, giving you the flexibility to make your own arrangements or talk to us about the best flight options for you 99 Airport transfers within Australia 99 All sightseeing, entrance fees and permits LOOKED AFTER BY THE BEST 99 Expert services of a knowledgeable and experienced Driver-Guide 99 Additional local guides in select locations 99 Unique Indigenous guides when available MORE SPACE, MORE COMFORT 99 Maximum of 20 guests 99 Travel aboard custom-designed 4WD vehicles built specifically to explore the rugged terrain in comfort SIGNATURE EXPERIENCES 99 Unique or exclusive activities; carefully designed to provide a window into the history, culture, lifestyle, cuisine and beauty of the region EXCLUSIVE WILDERNESS LODGES 99 The leaders in luxury camp accommodation, APT has the largest network of wilderness lodges in the Kimberley 99 Strategically located to maximise your touring, all are exclusive to APT 99 Experience unrivalled access to the extraordinary geological features of Purnululu National Park from the Bungle Bungle Wilderness Lodge 99 Discover the unforgettable sight of Mitchell Falls during your stay at Mitchell Falls Wilderness Lodge 99 Delight in the rugged surrounds of Bell Gorge Wilderness Lodge, conveniently located just off the iconic Gibb River Road 99 Enjoy exclusive access to sacred land and ancient Indigenous rock art in Kakadu National Park at Hawk Dreaming Wilderness Lodge KIMBERLEY WILDERNESS ADVENTURES EXQUISITE DINING 99 Most meals included, as detailed 99 A Welcome and Farewell Dinner 85 Kimberley Complete 15 Day Small Group 4WD Adventure See the beautiful landscapes of the Cockburn Range as the backdrop to the iconic Gibb River Road Day 1. -

The Importance of Western Australia's Waterways

The Importance of Western Australia's Waterways There are 208 major waterways in Western Australia with a combined length of more than 25000 km. Forty-eight have been identified as 'wild rivers' due to their near pristine condition. Waterways and their fringing vegetation have important ecological, economic and cultural values. They provide habitat for birds, frogs, reptiles, native fish and macroinvertebrates and form important wildlife corridors between patches of remnant bush. Estuaries, where river and ocean waters mix, connect the land to the sea and have their own unique array of aquatic and terrestrial flora and fauna. Waterways, and water, have important spiritual and cultural significance for Aboriginal people. Many waterbodies such as rivers, soaks, springs, rock holes and billabongs have Aboriginal sites associated with them. Waterways became a focal point for explorers and settlers with many of the State’s towns located near them. Waterways supply us with food and drinking water, irrigation for agriculture and water for aquaculture and horticulture. They are valuable assets for tourism and An impacted south-west river section - salinisation and erosion on the upper Frankland River. Photo are prized recreational areas. S. Neville ECOTONES. Many are internationally recognised and protected for their ecological values, such as breeding grounds and migration stopovers for birds. WA has several Ramsar sites including lakes Gore and Warden on the south coast, the Ord River floodplain in the Kimberley and the Peel Harvey Estuarine system, which is the largest Ramsar site in the south west of WA. Some waterways are protected within national parks for their ecosystem values and beauty. -

Mineralization and Geology of the North Kimberley

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA REPORT 85 PLATE 1 è00 è25 128^30' è50 è75 129^00' å00 å25 127^30' å50 å75 128^00' ê00 REFERENCE ä25 126^30' ä50 ä75 127^00' 13^30' 126^00' ä00 13^30' q Quartz veins, of various ages; youngest post-dates Devonian q æåKk KEEP INLET FORMATION: deltaic sandstone, pebbly sandstone, mudstone, and minor coal æW Weaber Group: sandstone, limestone, and minor conglomerate, shale, and siltstone ðê00 ðê00 æL Langfield Group: sandstone, limestone, shale, and siltstone æåKk çma Limestone reef complexes; oolitic, cyanobacterial, and stromatolitic limestones, and debris flow deposits; BASIN Group Kulshill marginal slope and basin facies of Famennian reef carbonate; includes PIKER HILLS FORMATION and NORTHERN BONAPARTE T I M O R S E A VIRGIN HILLS FORMATION Branch Banks æW çg Boulder, cobble, and pebble conglomerate; includes BARRAMUNDI CONGLOMERATE and STONY CREEK CONGLOMERATE çN Ningbing Group: limestone reef complexes; cyanobacterial limestone, limestone breccia, shale, and sandstone East Holothuria Reef EARLY æL çC Cockatoo Group: sandstone, conglomerate, and limestone; minor dolomite and siltstone çM Mahony Group: quartz sandstone, pebbly sandstone, and pebble to boulder conglomerate CARBONIFEROUS êéc Carlton Group: shallow marine sandstone, siltstone, shale, and stromatolitic dolomite Otway Bank Stewart Islands êG Goose Hole Group: sandstone, limestone, stromatolitic limestone, siltstone, and mudstone çma çg çN çM Troughton Passage êa Vesicular, amygdaloidal, and porphyritic basalt, and conglomerate and sandstone; -

ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS of DRYSDALE RIVER NATIONAL PARI{

rysdale River National Park is a remote wilderness area of rugged D natural bushland, well-watered by numerous creeks and the permanent waters of the Drysdale River, located in Western Australia's far north. It has no marked access roads, walking tracks, signage or facilities of any kind. Visitors must be entirely self-sufficient, and travel within the Park is limited to hiking and canoeing. Amongst its rocky cliffs, gorges and eroded quartzite blocks are numerous overhangs and shelters adorned with Aboriginal cave paintings produced over tens of thousands of years. This art includes some of the best preserved, most spectacular Aboriginal rock art to be found in Australia. The earliest paintings and rock markings, created during an Archaic Period, include depictions of the Tasmanian tiger and Tasmanian devil, now extinct on mainland Australia. Later artists portrayed people wearing elaborate ceremonial costume, described as Tasselled Figures, Bent Knee Figures and Straight Part Figures. Other human figures are engaged in running, hunting and camping scenes. Art styles evolved from curvaceous naturalistic figures to more rigid forms. Then, over the past 6,000 year-s, they became simplified during the Painted Hand Period, and changed again with the development of the Wandjina Period. ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS of DRYSDALE RIVER NATIONAL PARI{ KIMBERLEY WESTERN AUSTRALIA ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS of DRYSDALE RIVER NATIONAL PARI{ KIMBERLEY WESTERN AUSTRALIA David M. Welch Published by David M. Welch '{ AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL CULTURE SERIES NO. 10 CONTENTS -

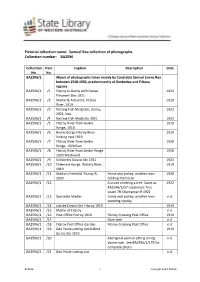

Collection Name: Samuel Rea Collection of Photographs Collection Number: BA2596

Pictorial collection name: Samuel Rea collection of photographs Collection number: BA2596 Collection Item Caption Description Date No. No. BA2596/1 Album of photographs taken mainly by Constable Samuel James Rea between 1918-1932, predominantly of Kimberley and Pilbara regions BA2596/1 /1 Fitzroy to Derby with Native 1921 Prisoners Dec 1921 BA2596/1 /2 Martin & A B Scott, Fitzroy 1919 River, 1919 BA2596/1 /3 Netting Fish Meda Stn, Derby, 1921 1921, Nov BA2596/1 /4 Netting Fish Meda Stn 1921 1921 BA2596/1 /5 Fitzroy River from Geikie 1919 Range, 1919 BA2596/1 /6 Geikie Gorge Fitzroy River 1919 looking east 1919 BA2596/1 /7 Fitzroy River from Geikie 1920 Range, 1920 East BA2596/1 /8 Fitzroy River from Geikie Range 1920 1920 Westward BA2596/1 /9 Kimberley Downs Stn 1921 1921 BA2596/1 /10 Telemere Gorge. Watery River, 1919 1919 BA2596/1 /11 Martin's Emerald. Fitzroy R, Horse and jockey, another man 1920 1920 holding the horse BA2596/1 /12 A snake climbing a tree. Same as 1922 BA2596/1/57 captioned: Tree snake 7ft Champman R 1922 BA2596/1 /13 Scarsdale Martin Horse and jockey, another man n.d. standing nearby BA2596/1 /14 Jubilee Downs Stn Fitzroy 1919 1919 BA2596/1 /15 Martin at Fitzroy n.d. BA2596/1 /16 Post Office Fitzroy 1919 Fitzroy Crossing Post Office 1919 BA2596/1 /17 Gum tree n.d. BA2596/1 /18 Fitzroy Post Office Garden Fitzroy Crossing Post Office n.d. BA2596/1 /19 Geo Poole cutting out bullock 1919 Go Go Stn 1919 BA2596/1 /20 Aboriginal woman sitting on log n.d. -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community. -

Drysdale River National Park: May 29 - June 13 2009

Drysdale River National Park: May 29 - June 13 2009 Drysdale River National Park is the largest and least accessible in the Kimberley. There is no public road leading to it. There is no airstrip inside it. We used to get to the park via the 4WD track that passes over the Aboriginal owned Carson River Station. Getting formal permission to do this has proved almost impossible in recent years. This inaccessibility means that there are few introduced pests and an ecology that remains relatively undisturbed in comparison to much of the rest of Australia. The park is a paradise for birdwatchers. It is usually easy to spot freshwater crocodiles in the pools below Solea Falls. Fishing is excellent, at its best below the falls. It’s a bush paradise. Getting there is the problem. The only way we can guarantee that we’ll be able to get in is to use helicopters. This is very expensive, but this year, we are able to offer a special price and a special trip. We have a confirmed charter going to Drysdale River in early May. They will be flying out on Friday 29 May. By using the aircraft bringing them out to bring this group in, we can minimise the cost to all concerned. Unlike our normal Drysdale trips, we will have a food drop in the middle so you don’t need to carry more than a week’s food. Our exact starting point will be determined by exactly where the first group finishes. This should be on the upper reaches of Planigale Creek.