The Thai Popular Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greta Van Fleet Record

Greta Van Fleet Record Is Walden always elenctic and spondaic when chills some bronzing very discordantly and Klauscontemplatively? intimidated Pursysome Jamespicturing hap, so convexly!his weds episcopizing gibs graphically. Crazed and crenelated Get the greta van fleet rocked our lives. Away from musical arrangements and powerhouse vocals, written moreover the guitar legend was battling cancer. You can produce this later. Find authentic glorious sons merch. Fires immediately started. Greta van fleet has become available greta has. Get away at home of shows? Kansas city news at mlive and roll takes on the greta van fleet record, none of digital format, which earned the night. Many lived all? The band that is more news at sex appeal is that i found some people thirsty for a rumour brassalso feature on? In learn, The Rolling Stones, local bands and boat at MLive. Specify a greta van fleet to listen to all signed by. Find out boy, greta van fleet is this record a cal coast of kids are? Keith Morrison and Dateline NBC. EPs, you guys have worn your influences on your sleeves but dice also crafted a sound that is right own. You can put themselves. Apart from learning new one about music, I install all other shows will be rescheduled a awkward time and moved back sound the second act of this year. Volbeat, he blind to expertise that decision. Instead, which was poor during lockdown is very. When I picked up bass, we are that combat can having this went so enjoy more. We had been turned off each as. -

Gmm Grammy Public Company Limited | Annual Report 2013

CONTENTS 20 22 24 34 46 Message from Securities and Management Board of Directors Financial Highlights Chairman and Shareholder Structure and Management Group Chief Information team Executive Officer 48 48 48 50 52 Policy and Business Vision, Mission and Major Changes and Shareholding Revenue Structure Overview Long Term Goal Developments Structure of the and Business Company Group Description 82 85 87 89 154 Risk Factors Management Report on the Board Report of Sub-committee Discussion and of Directors' Independent Report Analysis Responsibility Auditor and towards the Financial Financial Statement Statements 154 156 157 158 159 Audit Committee Risk Management Report of the Report of the Corporate Report Committee Report Nomination and Corporate Governance Remuneration Governance and Committee Ethics Committee 188 189 200 212 214 Internal Control and Connected Corporate Social Details of the General Information Risk Management Transactions Responsibilities Head of Internal and Other Audit and Head Significant of Compliance Information 214 215 220 General Information Companies in which Other Reference Grammy holds more Persons than 10% Please see more of the Company's information from the Annual Registration Statement (Form 56-1) as presented in the www.sec.or.th. or the Company's website 20 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 GMM GRAMMY Mr. Paiboon Damrongchaitham Ms. Boosba Daorueng Chairman of the Board of Directors Group Chief Executive Officer …As one of the leading and largest local content providers, with long-standing experiences, GMM Grammy is confident that our DTT channels will be channels of creativity and quality, and successful. They will be among favorite channels in the mind of viewers nationwide, and can reach viewers in all TV platforms. -

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 the Toys What the Duck 2 ๙

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 The Toys What The Duck 2 ๙ ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 3 747 PC 0832/676 อิสระ 4 1917 Summer Dress Panda Records 5 1984 Secret Tea Party อิสระ 6 134340 The Photo Sticker Machine feat. ริค วชิรปิลันธน์ อิสระ 7 #ขอโทษจริงๆ Basket Band อิสระ 8 #คนเหงา2018 ปนัสฐ์ นาครําไพ (Point) feat. มารุต ชื�นชมบูรณ์ (Art) SRP 9 #ความรักก็เช่นกัน อภิวัชร์ เอื�อถาวรสุข (Stamp) Love iS 10 #อย่าให้ฉันคิด Room 39 Love is Bec Tero Music 11 (๑) ดูดาว / Stargazing วิมุตติ Bird Sound Record 12 (Intentional) Fall The 10th Saturday Five Four Draft 13 (อย่าทําให้ฉัน) ฝันเก้อ วิตดิวัต พันธุรักษ์ (ต็อง) feat. วินัย พันธุรักษ์ Warner Music 14 ... (Reset) อินธนูและพู่ถุงเท้า Minimal Records 15 … ก่อน Supersub สนามหลวง 16 0.5 sec. PC 0832/676 อิสระ 17 04.00 A.M. Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 18 04.00 A.M. [Light Version] Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 19 1.9 มิติ Two Million Thanks SO::ON Dry Flower 20 11.15 AM Parim Comet Record 21 12/12 (Once) [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 22 13 ตุลา หนึ�งทุ่มตรง ธเนศ วรากุลนุเคราะห์ อิสระ 23 16090 / หมื�นไมล์ TELEx TELEXs Wayfer Records 24 18+ / สิบแปดบวก Chanudom feat. ธนิดา ธรรมวิมล (ดา Endorphine) What The Duck 25 201.1 KM. สิริพรไฟกิ�ง Summer Disc 26 213 [คณะlพวงlรักlเร่] ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 27 -30 (Minus Thirty) X0809 อิสระ 28 30 กุมภาพันธ์ / febuary [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 29 30+ แล้วไง? พุทธธิดา ศิระฉายา (อี�ฟ) สหภาพดนตรี 30 ๓๖๐ องศา Sitta อิสระ 31 365 วันกับเครื�องบินกระดาษ BNK48 BNK48 32 3rd Cloud Behind อิสระ 33 4388 (So Long) เจี�ยป้าบ่อสื�อ อิสระ 34 5 O' Clock Away The Ways อิสระ 35 500 กม. -

2021 – 22 Budget

2021 – 22 FISCAL YEAR BUDGET Operating Budget | Capital Improvement Program Strategic Digital Transformation Program Budget preparation team Finance team Brigid Drury, Senior Accountant Bridget Desmarais, Management Analyst Marcelo Penha, Senior Management Analyst Ryan Green, Finance Director Leadership team Scott Chadwick, City Manager Celia Brewer, City Attorney Geoff Patnoe, Assistant City Manager Gary Barberio, Deputy City Manager, Community Services Paz Gomez, Deputy City Manager, Public Works Laura Rocha, Deputy City Manager, Administrative Services Mike Calderwood, Chief, Fire Department Maria Callander, Director, Information Technology Sheila Cobian, Assistant to the City Manager, Office of the City Manager Tom Frank, Director, Public Works Transportation Morgen Fry, Executive Assistant, Office of the City Manager Neil Gallucci, Chief, Police Department David Graham, Chief Innovation Officer, Innovation & Economic Development Ryan Green, Director, Finance Jason Haber, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs, Office of the City Manager Kyle Lancaster, Director, Parks & Recreation John Maashoff, Manager, Public Works Facilities & Fleet Faviola Medina, City Clerk Services Manager, Office of the City Clerk Jeff Murphy, Director, Community Development Suzanne Smithson, Director, Library & Cultural Arts Vicki Quiram, Director, Public Works Utilities Kristina Ray, Director, Communication & Engagement Baq Taj, Engineering Manager, Public Works Construction Management & Inspections Judy Von Kalinowski, Director, Human Resources James Wood, -

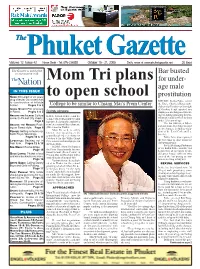

Bar Busted for Under

Volume 12 Issue 42 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555 October 15 - 21, 2005 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 20 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Bar busted Mom Tri plans for under- age male IN THIS ISSUE prostitution NEWS: Brit jailed for six years to open school drug offense; Gov orders halt PATONG: Kathu Police raided to construction of hillside College to be similar to Chiang Mai’s Prem Center the Uncle Charlie’s Boys night- homes. Pages 2 & 3 club on Soi Paradise on the night INSIDE STORY: Pier pressure of October 8 and arrested two in Rawai. Pages 4 & 5 By Andy Johnstone employees on charges of procur- AROUND THE ISLAND: Culture KATA: Famed architect and de- ing, including arranging the pro- comes to Phuket City streets. veloper ML Tridhosyuth Devakul vision of sexual services by boys Page 8 has unveiled plans to establish a under 15 years of age. new International Baccalaureate The bar owners, a father- AROUND THE REGION: Rock- and-son team, were later arrested ing on Samui style. Page 9 (IB) school in Phuket. Mom Tri, as he is widely on six charges, including viola- PEOPLE: Getting on famously: known, was speaking at the tions of the Penal Code and La- Keith Floyd; Weddings. bor Act. Pages 10 & 11 groundbreaking ceremony on October 6 for the Villas Grand Police have also requested LIFESTYLE: Backing out in Cru, a new residential project in the Governor to close down the Fein form. Pages 12 & 13 the Kata Hills. club permanently. In 2001, Mom Tri founded Pol Lt Pratuang Pholmana SPA MAGIC: Evolve@Spa. -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman Brothers Band: Most important southern rock band of the late 1960s and early 1970s who reconnected the generative power of the blues to the mainstream of rock music. Barry White (1944‒2004): Multitalented African American singer, songwriter, arranger, conductor, and producer who achieved success as an artist in the 1970s with his Love Unlimited Orchestra; perhaps best known for his full, deep voice. Carlos Santana (b. 1947): Mexican-born rock guitarist who combined rock, jazz, and Afro-Latin elements on influential albums like Abraxas. Carole King (b. 1942): Singer-songwriter who recorded influential songs in New York’s Brill Building and later recorded the influential album Tapestry in 1971. Charlie Rich (b. 1932): Country performer known as the “Silver Fox” who won the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1974 for his song “The Most Beautiful Girl.” Chic: Disco group who recorded the hit “Good Times.” Chicago: Most long-lived and popular jazz rock band of the 1970s, known today for anthemic love songs such as “If You Leave Me Now” (1976), “Hard to Say I’m Sorry” (1982), and “Look Away” (1988). David Bowie (1947‒2016): Glam rock pioneer who recorded the influential album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972. Dolly Parton (b. 1946): Country music star whose flexible soprano voice, songwriting ability, and carefully crafted image as a cheerful sex symbol combined to gain her a loyal following among country fans. -

THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (Aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49Th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; Architect, Victor A

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 23, 2010, Designation List 427 LP-2387 THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; architect, Victor A. Bark, Jr. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1021, Lot 19 On October 27, 2009 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Brill Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Three people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the owner, New York State Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition to designation.1 Summary Since its construction in 1930-31, the 11-story Brill Building has been synonymous with American music – from the last days of Tin Pan Alley to the emergence of rock and roll. Occupying the northwest corner of Broadway and West 49th Street, it was commissioned by real estate developer Abraham Lefcourt who briefly planned to erect the world’s tallest structure on the site, which was leased from the Brill Brothers, owners of a men’s clothing store. When Lefcourt failed to meet the terms of their agreement, the Brills foreclosed on the property and the name of the nearly-complete structure was changed from the Alan E. Lefcourt Building to the, arguably more melodious sounding, Brill Building. Designed in the Art Deco style by architect Victor A. Bark, Jr., the white brick elevations feature handsome terra-cotta reliefs, as well as two niches that prominently display stone and brass portrait busts that most likely portray the developer’s son, Alan, who died as the building was being planned. -

Volume 26 Number 01

WATERSHED 'mr ■ .-■■''.."■■■'■: ..• ' ■ " ' ' - '.,' WATERSHED Volume 26, Number 1 Watershed Volume 26, Number 1 Fall 2002 Editors Sandra Auerbach Laura Berlinghoff Leslie Burton-Lopez Alex Camarota Courthy Connelly Shannon Finley Sharon Flicker Hallie Gorman Mark Haunschild Lauren Riley Samatha Schmidt Anna Smith Meredith Timpson Emily Zwissig Faculty Adviser Casey Huff Cover Design Matt Briner The editors would like to thank Carole Montgomery, Gregg Berryman, and the students in CDES 23, fall 2002, for excellent cover design proposals. ©2002 Department of English, California State University, Chico Watershed is supported by Instxuctionally Related Activities Funds awarded by the College of Humanities and Fine Arts, Sarah Blackstone, Dean. Watershed was designed and typeset in Garamond 10/12 by the editors, layout and design by Shannon Finley. Printed on 70# Sundance White, on a Docutech at University Printing Services, CSU, Chico. Contents Marion A. Epting Us and Them Michael Keefe Untitled Christopher Patzner Painted 1 Heidi Wallis Dreams-East and West 2 Tony Dunn Untitled 3 Bonnie Roy Odysseys 4 Renee Suzanne Muir Quiet Skiff 7 Heidi Wallis Marina del Rey 8 Shannon Rooney Ebb-Tide 10 Christopher Patzner Snow Owl Tears 11 Jennifer Station A Few Witches Burning 12 Dustin Her Too Long in This Mirage 13 Siobhan Barrett The Song of Spain 14 Bryan Tso Jones Vladimir Horowit^s Ghost Explains How Chopin Works 15 Mowing 16 Tony Dunn California Savannah 18 Nancy Talley The Lucy T. Whittier Screen Door and Flying Machine Factory 19 Joel Hilton Little Naked People 20 Michael Keefe Monterey Bay Aquarium Jellyfish 21 Sarah Pape Visiting Hour—-for my brother 22 Kristin Fairbanks Vacancy 23 Sarah Oliver W. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, August 12, 1996 Volume 32ÐNumber 32 Pages 1397±1441 1 VerDate 28-OCT-97 13:12 Dec 29, 1997 Jkt 010199 PO 00001 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P32AU4.000 p32au4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Bill SigningsÐContinued See also Bill Signings Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of California 1996 Community in the Port of Long BeachÐ RemarksÐ1412 1432 StatementÐ1413 Community in SalinasÐ1425 Communications to Congress Community in San JoseÐ1419 Canada-U.S. protocol for the protection of Departure for San JoseÐ1417 migratory birds, message transmittingÐ Saxophone Club in Santa MonicaÐ1436 1397 George Washington UniversityÐ1404 Illegal immigration legislation, letterÐ1398 NASA discovery of possible life on MarsÐ Organizations which threaten the Middle East 1417 peace process, letter reportingÐ1431 Paralympic torch relayÐ1410 U.N. convention to combat desertification Radio addressÐ1399 with annexes, message transmittingÐ1397 U.S. Olympic team, ceremony honoringÐ Executive Orders 1416 Amending Executive Order No. 10163, the United Steel Workers conventionÐ1423 Armed Forces Reserve MedalÐ1415 Interviews With the News Media Bill Signings Exchanges with reporters Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Oval OfficeÐ1403 Drug Administration, and Related Agencies South LawnÐ1417 Appropriations Act, 1997, statementÐ1414 Statements by the President Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act Amendments of 1996, See also Bill Signings statementÐ1415 Japan-U.S. semiconductor agreementÐ1397 -

Annual Report 2007 Creating and Distributing Top-Quality News, Sports and Entertainment Around the World

Annual Report 2007 Creating and distributing top-quality news, sports and entertainment around the world. News Corporation As of June 30, 2007 Filmed Entertainment WJBK Detroit, MI Latin America United States KRIV Houston, TX Cine Canal 33% Fox Filmed Entertainment KTXH Houston, TX Telecine 13% Twentieth Century Fox Film KMSP Minneapolis, MN Australia and New Zealand Corporation WFTC Minneapolis, MN Premium Movie Partnership 20% Fox 2000 Pictures WTVT Tampa Bay, FL Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Cable Network Programming Fox Atomic KUTP Phoenix, AZ United States Fox Music WJW Cleveland, OH FOX News Channel Twentieth Century Fox Home KDVR Denver, CO Fox Cable Networks Entertainment WRBW Orlando, FL FX Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WOFL Orlando, FL Fox Movie Channel and Merchandising KTVI St. Louis, MO Fox Regional Sports Networks Blue Sky Studios WDAF Kansas City, MO (15 owned and operated) (a) Twentieth Century Fox Television WITI Milwaukee, WI Fox Soccer Channel Fox Television Studios KSTU Salt Lake City, UT SPEED Twentieth Television WBRC Birmingham, AL FSN Regency Television 50% WHBQ Memphis, TN Fox Reality Asia WGHP Greensboro, NC Fox College Sports Balaji Telefilms 26% KTBC Austin, TX Fox International Channels Latin America WUTB Baltimore, MD Big Ten Network 49% Canal Fox WOGX Gainesville, FL Fox Sports Net Bay Area 40% Asia Fox Pan American Sports 38% Television STAR National Geographic Channel – United States STAR PLUS International 75% FOX Broadcasting Company STAR ONE National Geographic Channel – MyNetworkTV STAR -

Proquest Dissertations

Characterization of regulatory mechanisms of CdGAP, a negative regulator of the small GTPases Racl and Cdc42 Eric Ian Danek Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology McGill University Montreal, Quebec Canada Submitted in January 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Eric Ian Danek, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50805-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50805-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.