Response to Public Comments Proposal of Certain Federal Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

The Following Document Comes to You From

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) ACTS AND RESOLVES AS PASSED BY THE Ninetieth and Ninety-first Legislatures OF THE STATE OF MAINE From April 26, 1941 to April 9, 1943 AND MISCELLANEOUS STATE PAPERS Published by the Revisor of Statutes in accordance with the Resolves of the Legislature approved June 28, 1820, March 18, 1840, March 16, 1842, and Acts approved August 6, 1930 and April 2, 193I. KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA, MAINE 1943 PUBLIC LAWS OF THE STATE OF MAINE As Passed by the Ninety-first Legislature 1943 290 TO SIMPLIFY THE INLAND FISHING LAWS CHAP. 256 -Hte ~ ~ -Hte eOt:l:llty ffi' ft*; 4tet s.e]3t:l:ty tfl.a.t mry' ~ !;;llOWR ~ ~ ~ ~ "" hunting: ffi' ftshiRg: Hit;, ffi' "" Hit; ~ mry' ~ ~ ~, ~ ft*; eounty ~ ft8.t rett:l:rRes. ~ "" rC8:S0R8:B~e tffi:re ~ ft*; s.e]38:FtaFe, ~ ~ ffi" 5i:i'ffi 4tet s.e]3uty, ~ 5i:i'ffi ~ a-5 ~ 4eeme ReCCSS8:F)-, ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ffi'i'El, 4aH ~ eRtitles. 4E; Fe8:50nable fee5 ffi'i'El, C!E]3C::lSCS ~ ft*; sen-ices ffi'i'El, ~ ft*; ffi4s, ~ ~ ~ ~ -Hte tFeasurcr ~ ~ eouRty. BefoFc tfte sffi4 ~ €of' ~ ~ 4ep i:tt;- ~ ffle.t:J:.p 8:s.aitional e1E]3cfisc itt -Hte eM, ~ -Hte ~ ~~' ~, ftc ~ ~ -Hte conseRt ~"" lIiajority ~ -Hte COt:l:fity COfi111'lissioReFs ~ -Hte 5a+4 coufity. Whenever it shall come to the attention of the commis sioner -

KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds

FALL/ WINTER 2015 THE NEWSLETTER OF MAINE RIVERS KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds Walking thigh-deep into a cold stream in January in Maine? The idea takes a little getting used to, but Paul Christman doesn’t have a hard time finding volunteers to do just that to help with salmon egg planting. Christman is a scientist with Maine Department of Marine Resource. His work, patterned on similar efforts in Alaska, involves taking fertilized salmon eggs from a hatchery and planting them directly into the cold gravel of the best stream habitat throughout the Sandy River, a Kennebec tributary northwest of Waterville. Yes, egg planting takes place in the winter. For Maine Rivers board member Sam Day plants salmon eggs in a tributary of the Sandy River more than a decade Paul has brought staff and water, Paul and crews mimic what female salmon volunteers out on snowshoes and ATVs, and with do: Create a nest or “redd” in the gravel of a river waders and neoprene gloves for this remarkable or stream where she plants her eggs in the fall, undertaking. Finding stretches of open stream continued on page 2 PROGRESS TO UNDERSTAND THE HEALTH OF THE ST. JOHN RIVER The waters of the St. John River flow from their headwaters in Maine to the Bay of Fundy, and for many miles serve as the boundary between Maine and Quebec. Waters of the St. John also flow over the Mactaquac Dam, erected in 1968, which currently produces a substantial amount of power for New Brunswick. Efforts are underway now to evaluate the future of the Mactaquac Dam because its mechanical structure is expected to reach the end of its service life by 2030 due to problems with the concrete portions of the dam’s station. -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1915 Part I

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 401 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1915 PART I. NORTH ATLANTIC SIOPE DRAINAGE BASINS NATHAN C. GROVES, Chief Hydraulic Engineer C. H. PIERCE, C. C. COVERT, and G. C. STEVENS. District Engineers Prepared in cooperation with the States of MAIXE, VERMONT, MASSACHUSETTS, and NEW YORK WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 1917 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 401 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1915 PART I. NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE DRAINAGE BASINS NATHAN C. GROVER, Chief Hydraulic Engineer C. H. PIERCE, C. C. COVERT; and G. C. STEVENS, District Engineers Geological Prepared in cooperation with the States MAINE, VERMONT, MASSACHUSETTS^! N«\f Yd] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPEBINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE "WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 15 CENTS PER COPY V CONTENTS. Authorization and scope of work........................................... 7 Definition of terms....................................................... 8 Convenient equivalents.................................................... 9 Explanation of data...................................................... 11 Accuracy of field data and computed results................................ 12 Cooperation.............................................................. -

Penobscot River 2007 Data Report July 2008

Penobscot River 2007 Data Report July 2008 Prepared by Donald Albert, P. E. Bureau of Land and Water Quality Division of Environmental Assessment DEPLW-0882 Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 Technical Design of Study ....................................................................................................1 Hydrologic Data ....................................................................................................................4 Ambient Chemical Data ........................................................................................................4 -DO, Temperature and Salinity .............................................................................................5 -Ultimate BOD ......................................................................................................................8 -Phosphorus Series ................................................................................................................11 -Nitrogen Series.....................................................................................................................13 -Chlorophyll-a .......................................................................................................................15 -Secchi disk transparency......................................................................................................17 Effluent Chemical Data .........................................................................................................18 -

1.NO-ATL Cover

EXHIBIT 20 (AR L.29) NOAA's Estuarine Eutrophication Survey Volume 3: North Atlantic Region July 1997 Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce EXHIBIT 20 (AR L.29) The National Estuarine Inventory The National Estuarine Inventory (NEI) represents a series of activities conducted since the early 1980s by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) to define the nation’s estuarine resource base and develop a national assessment capability. Over 120 estuaries are included (Appendix 3), representing over 90 percent of the estuarine surface water and freshwater inflow to the coastal regions of the contiguous United States. Each estuary is defined spatially by an estuarine drainage area (EDA)—the land and water area of a watershed that directly affects the estuary. The EDAs provide a framework for organizing information and for conducting analyses between and among systems. To date, ORCA has compiled a broad base of descriptive and analytical information for the NEI. Descriptive topics include physical and hydrologic characteristics, distribution and abundance of selected fishes and inver- tebrates, trends in human population, building permits, coastal recreation, coastal wetlands, classified shellfish growing waters, organic and inorganic pollutants in fish tissues and sediments, point and nonpoint pollution for selected parameters, and pesticide use. Analytical topics include relative susceptibility to nutrient discharges, structure and variability of salinity, habitat suitability modeling, and socioeconomic assessments. For a list of publications or more information about the NEI, contact C. John Klein, Chief, Physical Environ- ments Characterization Branch, at the address below. -

Dynamics of Larval Fish Abundance in Penobscot Bay, Maine

81 Abstract–Biweekly ichthyoplankton Dynamics of larval fi sh abundance surveys were conducted in Penobscot Bay, Maine, during the spring and early in Penobscot Bay, Maine summer of 1997 and 1998. Larvae from demersal eggs dominated the catch from late winter through spring, but Mark A. Lazzari not in early summer collections. Larval Maine Department of Marine Resources fi sh assemblages varied with tempera- P.O. Box 8 ture, and to a lesser extent, plankton West Boothbay Harbor, Maine 04575 volume, and salinity, among months. E-mail address: [email protected] Temporal patterns of larval fi sh abun- dance corresponded with seasonality of reproduction. Larvae of taxa that spawn from late winter through early spring, such as sculpins (Myoxocepha- lus spp.), sand lance (Ammodytes sp.), and rock gunnel (Pholis gunnellus) For most fi sh, the greatest mortality tial variation in species diver sity and were dominant in Penobscot Bay in occurs during early life stages (Hjort, abundance, and 3) to relate these vari- March and April. Larvae of spring to early summer spawners such as 1914; Cushing, 1975; Leggett and Deb- ations to differences in location and en- winter fl ounder (Pleuronectes america- lois, 1994). Therefore, it is essential that vironmental variables. nus) Atlantic seasnail (Liparis atlan- fi sh eggs and larvae develop in favorable ticus), and radiated shanny (Ulvaria habitats that maximize the probability subbifurcata) were more abundant in of survival. Bigelow (1926) recognized Materials and methods May and June. Penobscot Bay appears the signifi cance of the coastal shelf for to be a nursery for many fi shes; there- the production of fi sh larvae within the Field methods fore any degradation of water quality Gulf of Maine, noting that most larvae during the vernal period would have were found within the 200-m contour. -

Seafloor Features and Characteristics of the Black Ledges Area, Penobscot Bay, Maine, USA

Journal of Coastal Research SI 36 333-339 (ICS 2002 Proceedings) Northern Ireland ISSN 0749-0208 Seafloor Features and Characteristics of the Black Ledges Area, Penobscot Bay, Maine, USA. Allen M. Gontz, Daniel F. Belknap and Joseph T. Kelley Department of Geological Sciences, 111 Bryand Global Science Center, University of Maine, Orono, Maine, USA04469-5790. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The Black Ledges, a series of islands, shoals, and ledges in East Penobscot Bay, Maine, was mapped with digital sidescan sonar and shallow marine seismic reflection equipmentA total of 38 km2 of sidescan and 600 km of seismic data was collected during four cruises in 2000-2001. The sidescan sonar reveals a surficial geology dominated by muddy sediments with frequent, patchy outcrops of gravel and minor amounts of bedrock. There are seven large concentrations of pockmarks with populations totaling over 3500 in the areas of muddy sediments. Generally circular, pockmarks range in size from five to 75 meters in diameter and up to eight meters deep. Calculations show over 2 x 106 m3 of muddy sediment and pore water were removed from the system during pockmark formation. Seismic data reveal a simple stratigraphy of modern mud overlying late Pleistocene glaciomarine sediment, till and Paleozoic bedrock. Seismic data indicate areas of gas-rich sediments and gas- enhanced reflectors in close association with pockmarks, suggesting methane seepage as a cause of pockmark formation. Pockmarks are alsorecognized in areas lacking evidence of subsurface methane accumulations adding further validity to the late stage of development for the field. -

Essential Fish Habitat Assessment

APPENDIX L ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT (PHYSICAL HABITAT) JACKSONVILLE HARBOR NAVIGATION (DEEPENING) STUDY DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT ASSESSMENT JACKSONVILLE HARBOR NAVIGATION STUDY DUVAL COUNTY, FL Final Report January 2011 Prepared for: Jacksonville District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Prudential Office Bldg 701 San Marco Blvd. Jacksonville, FL 32207 Prepared by: Dial Cordy and Associates Inc. 490 Osceola Avenue Jacksonville Beach, FL 32250 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. III LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... III 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT DESIGNATION ................................................................. 6 2.1 Assessment ........................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Managed Species .................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 Penaeid Shrimp .................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1.1 Life Histories ............................................................................................... 9 2.2.1.1.1 Brown Shrimp ...................................................................................... -

Ibastoryspring08.Pdf

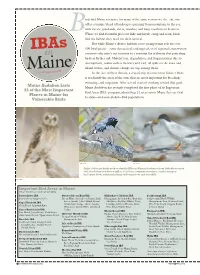

irds find Maine attractive for many of the same reasons we do—the state offers a unique blend of landscapes spanning from mountains to the sea, with forests, grasslands, rivers, marshes, and long coastlines in between. B Where we find beautiful places to hike and kayak, camp and relax, birds find the habitat they need for their survival. But while Maine’s diverse habitats serve an important role for over IBAs 400 bird species—some threatened, endangered, or of regional conservation in concern—the state’s not immune to a growing list of threats that puts these birds at further risk. Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation due to development, toxins such as mercury and lead, oil spills on the coast and Maine inland waters, and climate change are top among them. BY ANDREW COLVIN In the face of these threats, a crucial step in conserving Maine’s birds is to identify the areas of the state that are most important for breeding, wintering, and migration. After several years of working toward that goal, Maine Audubon Lists Maine Audubon has recently completed the first phase of its Important 22 of the Most Important Bird Areas (IBA) program, identifying 22 areas across Maine that are vital Places in Maine for Vulnerable Birds to state—and even global—bird populations. HANS TOOM ERIC HYNES Eight of the rare birds used to identify IBAs in Maine (clockwise from left): Short-eared owl, black-throated blue warbler, least tern, common moorhen, scarlet tanager, harlequin duck, saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrow, and razorbill. MIKE FAHEY Important -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) ACTS AND RESOLVES AS PASSED BY THE Ninety-sixth Legislature OF THE STATE OF MAINE Published by the Director of Legislative Research in accordance with subsection VI of section 26 of chapter 9 of the Revised Statutes of 1944. KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA, MAINE 1953 INDEX 1111 Index to Acts and Resolves Passed at Special Sessions of the Ninety-First, Ninety-Second and Ninety-Fourth Legislatures and the Regular Sessions of the Ninety-Second, Ninety-Third, Ninety-Fourth, Ninety-Fifth and Ninety-Sixth Legislatures. A 1945 1947 1949 1951 1953 Page Page Page Page Page ADATEIIIENT OF TAXES See Taxation; name of particular town, etc. ADBOTT BROOK Fishing .............••.•.•..•...••.... 880 ABSENT VOTING See Elections ACADEJIIES See Education ACADIA. NATIONAL PARK Deer, see Deer ACCIDENT INSURANCE See Insurance and Insurance Companies ACCIDENTS See Financial Responsibility Law; Insur ance and Insurance Companies; Motor Vehicles ACCOUNTS Assignment ..........•.......•..••..•• 140 Bank, impounded, charged off ••••..•••• 342, 1162, 1165 Joint, in banks, etc...•.•.•....••..•.•• 30, 23 134 Loan and building associations, share savings .............•..•.•.•........ 178 See Audit; Finances; State Accounts; State Auditor ACTIONS Executors and -

Social Studies Grade 3 Provincial Identity

Social Studies Grade 3 Curriculum - Provincial ldentity Implementation September 2011 New~Nouveauk Brunsw1c Acknowledgements The Departments of Education acknowledge the work of the social studies consultants and other educators who served on the regional social studies committee. New Brunswick Newfoundland and Labrador Barbara Hillman Darryl Fillier John Hildebrand Nova Scotia Prince Edward Island Mary Fedorchuk Bethany Doiron Bruce Fisher Laura Ann Noye Rick McDonald Jennifer Burke The Departments of Education also acknowledge the contribution of all the educators who served on provincial writing teams and curriculum committees, and who reviewed and/or piloted the curriculum. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Program Designs and Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Essential Graduation Learnings .................................................................................................................... 4 General Curriculum Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 6 Processes ..................................................................................................................................................