Hayward Shoreline Interpretive Center Pre-Trip Activities, Grades K-2 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeography of Pachygrapsus Transversus (Gibbes, 1850): The

Nauplius 13(2): 99-113, 2005 ^ Phylogeography of Pachygrapsus transversus (Gibbes, 1850): The effect of the American continent and the Atlantic Ocean as gene flow barriers and recognition of Pachygrapsus socius Stimpson 1871 as a valid species Schubart ', C. D.; Cuesta2, J. A. and Felder3, D. L. 1 Biologie I, Universitat Regensburg, D-93040 Regensburg, Germany, e-mail: [email protected] regensburg.de 2 Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucia, CSIC, Avda. Republica Saharaui, 2,11510 Puerto Real, Cadiz, Spain, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Laboratory for Crustacean Research, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA 70504- 2451, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Genetic and morphometric comparisons among a few specimens of the littoral crab Pachygrapsus transversus have revealed marked intraspecific differences between three different coastlines (Cuesta and Schubart, 1998). Here we build on the previous study by presenting a more comprehensive analysis covering the entire range of this species from the Galapagos Islands to Israel, based on 195 specimens for morphometric analysis and 39 individuals for genetic comparisons of the 16S mtDNA. It is confirmed that marked genetic differences are present between three major coastlines (eastern Pacific, western and eastern Adantic), whereas along single coastlines there is mostly high genetic homogeneity. Morphometric analyses also allow distinction of adult specimens from the three coastlines. In contrast, larval morphological and morphometric differences were less consistent and cannot be used to separate zoea I stages from the different megapopulations. In addition to the genetic separation of populations from different coastlines, this study provides new evidence for less marked, but consistent genetic differentiation between European and northern African populations of P. -

Long-Billed Curlew Distributions in Intertidal Habitats: Scale-Dependent Patterns Ryan L

LONG-BILLED CURLEW DISTRIBUTIONS IN INTERTIDAL HABITATS: SCALE-DEPENDENT PATTERNS RYAN L. MATHIS, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, Cali- fornia 95521 (current address: National Wild Turkey Federation, P. O. Box 1050, Arcata, California 95518) MARK A. ColwELL, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521; [email protected] LINDA W. LEEMAN, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (current address: EDAW, Inc., 2022 J. St., Sacramento, California 95814) THOMAS S. LEEMAN, Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (current address: Environmental Science Associates, 8950 Cal Center Drive, Suite 300, Sacramento, California 95826) ABSTRACT. Key ecological insights come from understanding a species’ distribu- tion, especially across several spatial scales. We studied the distribution (uniform, random, or aggregated) at low tide of nonbreeding Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) at three spatial scales: within individual territories (1–8 ha), in the Elk River estuary (~50 ha), and across tidal habitats of Humboldt Bay (62 km2), Cali- fornia. During six baywide surveys, 200–300 Long-billed Curlews were aggregated consistently in certain areas and were absent from others, suggesting that foraging habitats varied in quality. In the Elk River estuary, distributions were often (73%) uniform as curlews foraged at low tide, although patterns tended toward random (27%) when more curlews were present during late summer and autumn. Patterns of predominantly uniform distribution across the estuary were a consequence of ter- ritoriality. Within territories, eight Long-billed Curlews most often (75%) foraged in a manner that produced a uniform distribution; patterns tended toward random (16%) and aggregated (8%) when individuals moved over larger areas. -

Brief Description of Project

Detailed Background on Existing Resource Conditions in Project/Study Area Giacomini Wetland Restoration Project Golden Gate National Recreation Area/ Point Reyes National Seashore Land Use: The Giacomini Ranch has been used for dairy farming since 1917. The Giacominis established their operation in the 1940s with diking of what is now referred to as the East and West Pastures and are still farming the ranch currently. The National Park Service’s reservation of use agreement with the Giacominis ends in 2007 at which the dairy operation will cease, and the entire 563 acres will be under the National Park Service (Park Service) ownership and management. Olema Marsh, which is directly south of the Giacomini Ranch in the Olema Valley, has been owned by the non-profit organization, Audubon Canyon Ranch. The marsh is primarily used by the public for walking, birding, and sightseeing opportunities. The West Marin area, including Point Reyes National Seashore (Seashore) and north district of Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), is largely rural and comprised of agricultural operations and small residential communities. The dominant type of agriculture within the region is dairy and beef cattle operations. South of Olema Marsh lies pasturelands that are owned by the Park Service and grazed under lease by beef cattle. Leased beef cattle grazing also occurs near Park Service land at Railroad Point northeast of the Giacomini Ranch. Otherwise, most of the Giacomini Ranch and Olema Marsh is surrounded by the towns of Point Reyes Station and Inverness Park, which consist largely of residential homes and small businesses. To the north of Giacomini Ranch lies undiked marshlands that are owned by the State Lands Commission. -

Pachygrapsus Transversus

Population biology of two sympatric crabs: Pachygrapsus transversus (Gibbes, 1850) (Brachyura, Grapsidae) and Eriphia gonagra (Fabricius, 1781) (Brachyura, Eriphidae) in reefs of Boa Viagem beach, Recife, Brazil MARINA DE SÁ LEITÃO CÂMARA DE ARAÚJO¹*, DAVID DOS SANTOS AZEVEDO², JULIANE VANESSA CARNEIRO DE LIMA SILVA3, CYNTHIA LETYCIA FERREIRA PEREIRA1 & DANIELA DA SILVA CASTIGLIONI4,5 1. Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE), Coleção Didática de Zoologia (CDZ/UPE), Faculdade de Ciências, Educação e Tecnologia (FACETEG), Campus Garanhuns, Rua Capitão Pedro Rodrigues, 105, São José, CEP 55290-000, Garanhuns, PE. 2. Instituto Federal de Educação Ciência e Tecnologia de Pernambuco (IFPE), Av. Prof. Luiz Freire, 500, Cidade Universitária, CEP 55740-540, Recife, PE. 3. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Zoologia, Av. Professor Moraes Rego, s-n, Cidade Universitária, CEP 50670-901, Recife, PE. 4. Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Departamento de Zootecnia e Ciências Biológicas, Campus de Palmeira das Missões, Avenida Independência, 3751, Bairro Vista Alegre, CEP 983000-000, Palmeira das Missões, RS. 5. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Animal, Centro de Ciências Naturais e Exatas, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Prédio 17, sala 1140-D, Cidade Universitária, Camobi, km 9, Santa Maria, RS. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract. This study characterizes the population biology of two crabs: Pachygrapsus transversus and Eriphia gonagra from reefs at Boa Viagem Beach, Pernambuco. Carapace width (CW) was measured and all animals were sexed. A total of 1.174 specimens of P. transversus and 558 specimens of E. gonagra were sampled. -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

SGCN) - Amphibians

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: June 13, 2014 Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) - Amphibians High Regional ConservationPriority USFWS Birds of ConservationUSFWS ConcernBirdsof ClimateChange Vulnerability Northeast Odonate Assessment NortheastOdonate RecentSignificant Decline AmericanFisheries Society North American WaterbirdNorthAmerican RediscoveryPotential ShorebirdNorthAtlantic UnderstudiedTaxa Risk Of ExtirpationRiskOf Regional Endemic ShorebirdNational Partners In Flight Partners In MESA Proposed MESA FederalStatus IUCN Red List IUCN NatureServe State Status State Criteria1 Criteria2 Criteria3 Criteria4 Criteria5 Criteria6 Criteria7 COSEWIC NEWDTC NEPARC RSGCN ASMFC CommonName ScientificName Anura ( frogs and toads ) Northern Leopard Lithobates pipiens X X X Frog Mink Frog Lithobates X septentrionalis Caudata ( salamanders ) Blue-spotted Ambystoma laterale X X X Salamander Northern Spring Gyrinophilus X X Salamander porphyriticus porphyriticus Risk of Extirpation: Critically Endangered [CR]; Endangered [E] or [EN]; Threatened [T]; Vulnerable [VU]; Candidate [C]; Proposed Endangered [PE]; Proposed Threatened [PT] Amphibians Group Page 1 of 1 DRAFT Priority 2 SGCN Report - Page 1 of 33 Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: June 13, 2014 Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) - Aquatic And Terrestrial Snails High Regional ConservationPriority USFWS Birds of ConservationUSFWS ConcernBirdsof ClimateChange Vulnerability Northeast Odonate Assessment NortheastOdonate -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

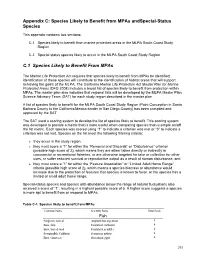

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Wildlife Ecology Provincial Resources

MANITOBA ENVIROTHON WILDLIFE ECOLOGY PROVINCIAL RESOURCES !1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank: Olwyn Friesen (PhD Ecology) for compiling, writing, and editing this document. Subject Experts and Editors: Barbara Fuller (Project Editor, Chair of Test Writing and Education Committee) Lindsey Andronak (Soils, Research Technician, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) Jennifer Corvino (Wildlife Ecology, Senior Park Interpreter, Spruce Woods Provincial Park) Cary Hamel (Plant Ecology, Director of Conservation, Nature Conservancy Canada) Lee Hrenchuk (Aquatic Ecology, Biologist, IISD Experimental Lakes Area) Justin Reid (Integrated Watershed Management, Manager, La Salle Redboine Conservation District) Jacqueline Monteith (Climate Change in the North, Science Consultant, Frontier School Division) SPONSORS !2 Introduction to wildlife ...................................................................................7 Ecology ....................................................................................................................7 Habitat ...................................................................................................................................8 Carrying capacity.................................................................................................................... 9 Population dynamics ..............................................................................................................10 Basic groups of wildlife ................................................................................11 -

Bird-A-Thon San Diego County Team: Date

Stilts & Avocets Forster's Tern Red-tailed Hawk Bird-a-Thon Pheasants & Turkeys Black-necked Stilt Royal Tern Barn Owls Ring-necked Pheasant American Avocet Elegant Tern Barn Owl San Diego County Wild Turkey Plovers Black Skimmer Typical Owls Grebes Black-bellied Plover Loons Western Screech-Owl Pied-billed Grebe Snowy Plover Common Loon Great Horned Owl Team: Eared Grebe Semipalmated Plover Cormorants Burrowing Owl Western Grebe Killdeer Brandt's Cormorant Kingfishers Date: Clark's Grebe Sandpipers & Phalaropes Double-crested Cormorant Belted Kingfisher Ducks, Geese & Swans Pigeons & Doves Whimbrel Pelicans Rock Pigeon Brant Long-billed Curlew American White Pelican Woodpeckers Canada Goose Band-tailed Pigeon Marbled Godwit Brown Pelican Acorn Woodpecker Eurasian Collared-Dove Wood Duck Black Turnstone Bitterns, Herons & Egrets Downy Woodpecker Common Ground-Dove Blue-winged Teal Sanderling Great Blue Heron Nuttall's Woodpecker White-winged Dove Cinnamon Teal Least Sandpiper Great Egret Northern Flicker Mourning Dove Northern Shoveler Western Sandpiper Snowy Egret Caracaras & Falcons Cuckoos, Roadrunners & Anis Short-billed Dowitcher Little Blue Heron Gadwall American Kestrel Greater Roadrunner Eurasian Wigeon Long-billed Dowitcher Green Heron Peregrine Falcon Swifts American Wigeon Spotted Sandpiper Black-crowned Night-Heron New World Parrots Vaux's Swift Wandering Tattler Yellow-crowned Night-Heron Mallard Red-crowned Parrot White-throated Swift Northern Pintail Willet Ibises & Spoonbills Red-maked Parakeet Hummingbirds Green-winged -

Pacific Ocean

124° 123° 122° 121° 42° 42° 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 ° 32 41° 41 31 29 30 27 28 26 25 24 23 22 21 ° ° 40 20 40 19 18 17 16 15 PACIFIC OCEAN 14 13 ° ° 39 12 39 11 10 9 8 6 7 4 5 20 0 20 3 MILES 1 2 38° 38° 124° 123° 122° 121° Prepared for: Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department Of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sacramento, California Seattle, Washington Prepared by: RESEARCH PLANNING, INC. Columbia, SC 29202 ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY INDEX MAP 123°00’00" 122°52’30" 38°07’30" 38°07’30" TOMALES BAY STATE PARK P O I N T R E Y E S N A T I O N A L S E A S H O R E ESTERO DE LIMANTOUR RESERVE POINT REYES NATIONAL SEASHORE 38°00’00" 38°00’00" POINT REYES HEADLAND RESERVE GULF OF THE FARALLONES NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY 123°00’00" 122°52’30" ATMOSPH ND ER A IC IC A N D A M E I Prepared for C N O I S L T R A A N T O I I O T N A N U . E S. RC DE E PA MM RTMENT OF CO Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1.50 1KILOMETER 1.50 1MILE PUBLISHED: SEPTEMBER 1994 DRAKES BAY, CALIF. -

The Crabs from Mayotte Island (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura)

THE CRABS FROM MAYOTTE ISLAND (CRUSTACEA, DECAPODA, BRACHYURA) Joseph Poupin, Régis Cleva, Jean-Marie Bouchard, Vincent Dinhut, and Jacques Dumas Atoll Research Bulletin No. 617 1 May 2018 Washington, D.C. All statements made in papers published in the Atoll Research Bulletin are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Smithsonian Institution or of the editors of the bulletin. Articles submitted for publication in the Atoll Research Bulletin should be original papers and must be made available by authors for open access publication. Manuscripts should be consistent with the “Author Formatting Guidelines for Publication in the Atoll Research Bulletin.” All submissions to the bulletin are peer reviewed and, after revision, are evaluated prior to acceptance and publication through the publisher’s open access portal, Open SI (http://opensi.si.edu). Published by SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 https://scholarlypress.si.edu/ The rights to all text and images in this publication are owned either by the contributing authors or by third parties. Fair use of materials is permitted for personal, educational, or noncommercial purposes. Users must cite author and source of content, must not alter or modify the content, and must comply with all other terms or restrictions that may be applicable. Users are responsible for securing permission from a rights holder for any other use. ISSN: 0077-5630 (online) This work is dedicated to our friend Alain Crosnier, great contributor for crab sampling in Mayotte region between 1958-1971 and author of several important taxonomic contributions in the region. -

American Avocet Breeding Habitat, Behaviour and Use of Nesting Platforms at Kelowna, British Columbia

Avocet breeding habitat, behaviour, and nesting platform use Gyug and Weir 13 American Avocet breeding habitat, behaviour and use of nesting platforms at Kelowna, British Columbia Les W. Gyug1 and Jason T. Weir2 1 Okanagan Wildlife Consulting, 3130 Ensign Way, West Kelowna, BC V4T 1T9 [email protected] 2 Dept. of Biological Sciences and Dept. of Ecology and Evolution, University of Toronto, 1265 Military Trail, Toronto, ON M1C 1A4 [email protected] Abstract: The largest and most consistently used American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) colony in British Columbia is located in the southern half of the former Alki Lake, Kelowna. This lake was a landfill active from the 1960’s to 1980’s, and is now slated to be filled in completely as the landfill reexpands into the remnants of the lake. Here, we report avocet behaviour, nest conditions and foraging habitat characteristics in 1999 at Alki Lake and five other wetlands in the Kelowna area to inform future mitigation strategies for this colony. Thirteen breeding pairs initiated 21 nests (including renesting after failed attempts) at Alki Lake in 1999, with no nests in other Kelowna area localities. Fifteen nests were on islands, five on 1.2 m square floating nest platforms, and one on a shoreline mudflat. Nesting on floating nest platforms had not been previously reported for American Avocets. Foraging areas regularly used by individual pairs were not necessarily adjacent to the nest, and increased from 0.32 ha during the incubation period to 0.53 ha after hatching. Avocets foraged primarily in soft silt substrates along nonvegetated shorelines and in shallow mudflats at a mean depth of 10 cm.