Screening Gender Gender Portrayal and Programme Making Routines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

An Film Partners, Zdf / Arte, Mam, Cnc, Medienboard Berlin Brandenburg Comme Des Cinemas, Nagoya Broadcasting Network and Twenty Twenty Vision

COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION AN FILM PARTNERS, ZDF / ARTE, MAM, CNC, MEDIENBOARD BERLIN BRANDENBURG COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION SYNOPSIS Sentaro runs a small bakery that serves dorayakis - pastries filled with sweet red bean paste(“an”) . When an old lady, Tokue, offers to help in the kitchen he reluctantly accepts. But Tokue proves to have magic in her hands when it comes to making “an”. Thanks to her secret recipe, the little business soon flourishes… And with time, Sentaro and Tokue will open their hearts to reveal old wounds. 113 minutes / Color / 2.35 / HD / 5.1 / 2015 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Cherry trees in full bloom remind us of death. I do not know of any other tree whose flowers blossom in such a spectacular way, only to have their petals scatter just as suddenly. Is this the reason behind our fascination for blossoming cherry trees? Is this why we are compelled to see a reflection of our own lives in them? Sentaro, Tokue and Wakana meet when the cherry trees are in full bloom. The trajectories of these three people are very different. And yet, their souls cross paths and meet one another in the same landscapes. Our society is not always predisposed to letting our dreams become reality. Sometimes, it swallows up our hopes. After learning that Tokue is infected with leprosy, the story pulls us into a quest for the very essence of what makes us human. As a director, I have the honour and pleasure of exploring different lives through cinema, as is the case with this film. -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — the Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine

MARIE–HÉLÈNE GUTBERLET ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ Towards an Aesthetic of the Migrant Self — The Film Le Clandestin by José Zeka Laplaine A BSTRACT: The representation of migrant arrivals in Europe is at the centre of this investigation of Zeka Laplaine’s short film Le Clandestin (1996). Placing the short film in the context of the African cinematographic traditions of earlier, more conventional, migrant narratives, the essay shows that the associative structure and the postmodern use of irony and magical realism in this short film question both our sense of familiarity and the promise of effortless transcultural communication. 1 OST FILMS (cinema and television productions) dealing with African migration, especially migration to Europe, are produced M and realized by European film and broadcasting companies. They reflect a specific attitude towards individuals and their situation and towards the issue of foreign presence on European soil. The portrayal and production of the African migrant in European media represents a complex field of poli- tically, socially, racially, and aesthetically relevant influences that would need to be analysed specifically. Awareness of these issues has spread beyond the academic field: everybody is more or less familiar with the images of African migrants, with the unease, the exaggerations, humiliations, and transformations taking place in the production of these images, and has learned to view against the grain and sometimes see behind the obvious. Another concern underlies the present essay: are there other ways of expressing and showing the arrival of © Transcultural Modernities: Narrating Africa in Europe, ed. Elisabeth Bekers, Sissy Helff & Daniela Merolla (Matatu 36; Amsterdam & New York NY: Editions Rodopi, 2009). -

Women and Men in the News

Nordic Council of Ministers TemaNord 2017:527 Women and men in the news and men in Women 2017:527 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org WOMEN AND MEN IN THE NEWS The media carry significant notions of social and cultural norms and values and have a powerful role in constructing and reinforcing gendered images. The news WOMEN AND MEN in particular has an important role in how notions of power are distributed in the society. This report presents study findings on how women and men are represented in the news in the Nordic countries, and to what extent women and IN THE NEWS men occupy the decision-making positions in the media. The survey is based on the recent findings from three cross-national research projects. These findings REPORT ON GENDER REPRESENTATION IN NORDIC NEWS CONTENT are supported by national studies. The results indicate that in all the Nordic AND THE NORDIC MEDIA INDUSTRY countries women are underrepresented in the news media both as news subjects and as sources of information. Men also dominate in higher-level decision-making positions. The report includes examples of measures used to improve the gender balance in Nordic news. Women and men in the news Report on gender representation in Nordic news content and the Nordic media industry Saga Mannila TemaNord 2017:527 Women and men in the news Report on gender representation in Nordic news content and the Nordic media industry Saga Mannila ISBN 978-92-893-4973-4 (PRINT) ISBN 978-92-893-4974-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-92-893-4975-8 (EPUB) http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2017-527 TemaNord 2017:527 ISSN 0908-6692 Standard: PDF/UA-1 ISO 14289-1 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2017 Layout: NMR Print: Rosendahls Printed in Denmark Although the Nordic Council of Ministers funded this publication, the contents do not necessarily reflect its views, policies or recommendations. -

Feminisms 1..277

Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) and Feminist Identities at the Borders Involving the Isolated Female TV Detective in Scandinavian-Noir 29 Janet McCabe Lena Dunham’s Girls: Can-Do Girls, -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

Challenging Gender and Racial Stereotypes in Online Spaces Alternative Storytelling Among Latino/A Youth in the U.S

Challenging Gender and Racial Stereotypes in Online Spaces Alternative Storytelling among Latino/a Youth in the U.S. Alexandra Sousa & Srividya Ramasubramanian Media play an important role in perpetuating racial and gender stereotypes that harm the self-esteem and self-concept of marginalized youth, especially for Latino/a youth in the US context. However, this article illustrates that through a participatory media and media literacy approach, media can also become part of the solution. The main aim of this article is to document Latinitas, the first digital magazine in the United States cre- ated by and for young Latinas that challenges stereotypes through participatory digital storytelling. Explored through an interview with one of Latinitas’ co-founders and press coverage about the organization, this case study sheds light on the importance of alterna- tive community-based initiatives for minority youth to redefine their identities in their own terms. The findings shed light on how to design alternative youth media programs, negotiate funding, build relationships with the surrounding community, and adapt to the changing media landscape. Such initiatives point to the importance of media literacy programs and participatory storytelling initiatives aimed at redefining youth identity and empowering youth voices. Existing research informs us that media play an important role in the formation and sus- tenance of gender stereotypes (Mazzarella, 2013), which are also culturally constructed in ways that intersect with other markers of identity and difference, such as race/ethnicity and socio-economic status (Rivera & Valdivia, 2013). One group in the United States that is particularly affected by this phenomenon, and in predominately negative ways, is young Latina women (Molina-Guzman & Valdivia, 2004; Valdivia, 2010). -

The Public Service Broadcasting Culture

The Series Published by the European Audiovisual Observatory What can you IRIS Special is a series of publications from the European Audiovisual Observatory that provides you comprehensive factual information coupled with in-depth analysis. The expect from themes chosen for IRIS Special are all topical issues in media law, which we explore for IRIS Special in you from a legal perspective. IRIS Special’s approach to its content is tri-dimensional, with overlap in some cases, depending on the theme. terms of content? It offers: 1. a detailed survey of relevant national legislation to facilitate comparison of the legal position in different countries, for example IRIS Special: Broadcasters’ Obligations to Invest in Cinematographic Production describes the rules applied by 34 European states; 2. identifi cation and analysis of highly relevant issues, covering legal developments and trends as well as suggested solutions: for example IRIS Special, Audiovisual Media Services without Frontiers – Implementing the Rules offers a forward-looking analysis that will continue to be relevant long after the adoption of the EC Directive; 3. an outline of the European or international legal context infl uencing the national legislation, for example IRIS Special: To Have or Not to Have – Must-carry Rules explains the European model and compares it with the American approach. What is the source Every edition of IRIS Special is produced by the European Audiovisual Observatory’s legal information department in cooperation with its partner organisations and an extensive The Public of the IRIS Special network of experts in media law. The themes are either discussed at invitation-only expertise? workshops or tackled by selected guest authors. -

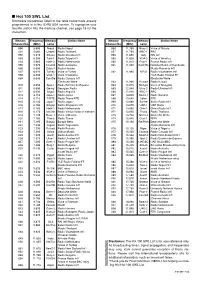

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We Welcome Conrad Tao Sakari

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We welcome Conrad Tao Sakari Oramo conductor Conrad Tao piano Lotta Emanuelsson presenter Andrew Norman: Suspend, a fantasy for piano and orchestra 1 Béla Bartók: Divertimento for String Orchestra 1. Allegro non troppo 2. Molto adagio 3. Allegro assai Conrad Tao – “shaping the future of classical music” “Excess. I find it to be for me like the four, and performed Mozart’s A-major pia- most vividly human aspect of musical no concerto at the age of eight. He was performance,” says pianist Conrad Tao (b. nine when the family moved to New York, 1994). And “excess” really is a good word where he nowadays lives. Beginning his to describe his superb technique, his pro- piano studies in Chicago, he continued at found interpretations and his emphasis on the Juilliard School, New York, and atten- the human aspect in general. ded Yale for composition. Tao has a wide repertoire ranging from Tao has had a manager ever since Bach to the music of today. He has also he was twelve. As a youngster, he also won recognition as a composer, and one learnt the violin, and several times in who, he says, views his keyboard perfor- 2008/2009 played both the E-minor vio- mances through the eyes of a composer. lin concerto and the first piano concerto His many talents and his ability to cross by Mendelssohn at one and the same con- traditional borders have indeed made him cert, but he soon gave up the violin. a notable influencer and a model for ot- Despite having all the hallmarks of a hers.