An Exploration of a Beginning Undergraduate Music Student Conducting with Expressivity by Alexander Minh Wimmer B.M., University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Techniques in Music Psychology: an Update

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Goldsmiths Research Online Statistical techniques in music psychology: An update Daniel M¨ullensiefen 1 Introduction Music psychology as a discipline has its origins at the end of the 19th century and ever since then, empirical methods have been a core part in this field of research. While its experimental and analytical methods have mainly been related to methodology employed in general psychology, several statistical techniques have emerged over the course of the past century being specific for empirical research in music psychology. These core methods have been described in a few didactic and summarising publications at several stages of the discipline’s history (see e.g. Wundt, 1882; B¨ottcher & Kerner, 1978; Windsor, 2001, or Beran, 2004 for a very technical overview), and these publications have been valuable resources to students and researchers alike. In contrast to these texts with a rather didactical focus, the objective of this chapter is to provide an overview of a range of novel statistical techniques that have been employed in recent years in music psychology research.1 This overview will give enough insight into each technique as such. The interested reader will then have to turn to the original publications, to obtain a more in-depth knowledge of the details related to maths and the field of application. Empirical research into auditory perception and the psychology of music might have its beginnings in the opening of the psychological laboratory by Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig in 1879 where experiments on human perception were conducted, and standards for empirical research and analysis were developed. -

The Impact of Music on Studying Ability in College Students

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Celebrating Scholarship and Creativity Day Undergraduate Research 4-26-2018 The Impact of Music on Studying Ability in College Students Nathaniel T. Lutmer College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/ur_cscday Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lutmer, Nathaniel T., "The Impact of Music on Studying Ability in College Students" (2018). Celebrating Scholarship and Creativity Day. 39. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/ur_cscday/39 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Celebrating Scholarship and Creativity Day by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 RUNNING HEAD: MUSIC AND STUDYING ABILITY The Impact of Music on Studying Ability in College Students Nathaniel T. Lutmer College of St. Benedict and Saint John’s University Author Note Nathaniel T. Lutmer, Department of Psychology, College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University Corresponding concerns regarding this article should be addressed to Nathaniel Lutmer, Department of Psychology, College of St. Benedict and Saint John’s University, Collegeville, MN 56321 Contact: [email protected] 2 RUNNING HEAD: MUSIC AND STUDYING ABILITY Abstract This study investigates the relationship between listening to music and studying ability in college students. This study was conducted by utilizing a convenience sampling technique to have participants partake in the study. Each participant was randomly assigned to either a control or one of two experimental groups based on block-random assignment. -

FIVE CHALLENGES and SOLUTIONS in ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION Page 1 of 10

FIVE CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS IN ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION Page 1 of 10 Volume 5, No. 1 September 2007 FIVE CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS IN ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION David G. Hebert Boston University [email protected] “Nearly 600 graduate students?”1 As remarkable as it may sound, that is the projected student population for the online graduate programs in music education at Boston University School of Music by the end of 2007. With the rapid proliferation of online courses among mainstream universities in recent years, it is likely that more online music education programs will continue to emerge in the near future, which begs the question of what effects this new development will have on the profession. Can online education truly be of the same quality as a traditional face-to-face program? How is it possible to effectively manage such large programs, particularly at the doctoral level? For some experienced music educators, it may be quite difficult to set aside firmly entrenched reservations and objectively consider the new possibilities for teaching and research afforded by recent technology. Yet the future is already here, and nearly 600 music educators have seized the opportunity. Through online programs, the internet has become the latest tool for offering professional development to practicing educators who otherwise would not have access, particularly those currently engaged in full-time employment or residing in rural areas. Recognizing the new opportunities afforded by recent technological developments, Director of the Boston University School of Music, Professor Andre De Quadros and colleagues launched the nation’s first online doctoral program in music education in 2005. -

An Introduction to Music Studies Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AN INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC STUDIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Samson,J. P. E. Harper-Scott | 310 pages | 31 Jan 2009 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521603805 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom An Introduction to Music Studies PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. An analysis of sociomusicology, its issues; and the music and society in Hong Kong. Critical Entertainments: Music Old and New. Other Editions 6. The examination measures knowledge of facts and terminology, an understanding of concepts and forms related to music theory for example: pitch, dynamics, rhythm, melody , types of voices, instruments, and ensembles, characteristics, forms, and representative composers from the Middle Ages to the present, elements of contemporary and non-Western music, and the ability to apply this knowledge and understanding in audio excerpts from musical compositions. An Introduction to Music Studies by J. She has been described by the Harvard Gazette as "one of the world's most accomplished and admired music historians". The job market for tenure track professor positions is very competitive. You should have a passion for music and a strong interest in developing your understanding of music and ability to create it. D is the standard minimum credential for tenure track professor positions. Historical studies of music are for example concerned with a composer's life and works, the developments of styles and genres, e. Mus or a B. For other uses, see Musicology disambiguation. More Details Refresh and try again. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. These models were established not only in the field of physical anthropology , but also cultural anthropology. -

SEM Student News Vol. 7

SEM{STUDENTNEWS} The Society for Ethnomusicology’s only publication run by students, for students. IN THIS ISSUE Ethnomusicology + Inter/disciplinarity Letter from the President 1 Student Union Update 3 The State of the Field 4 Dear SEM 6 Job Seeking Outside Academia 8 Volume 7 | Fall/Winter 2013 Volume Ethnomusicology, Jazz Education + Record Production 9 Conceptualizing Global Music Education 11 Expanding the Reach of Ethnomusicology 12 Join your peers by Ethnomusicology ++ : A Bibliography 13 ‘liking’ us on Facebook and get Our Staff 17 the latest updates and calls for submissions! Disciplinarity and Interdisciplinarity in Ethnomusicology a letter from the president of sem The choice of interdisciplinarity as anthropologists concerned with study of a set of natural-kind the theme of this issue of SEM music as a cultural phenomenon things-in-the-world (such as Student News usefully returns a were an important driving force in invertebrates or stars or minds) but longstanding concern of our field the foundation of our field. But rather as a group of people to the spotlight of critical ethnomusicology’s history has working in concord or conflict to attention. From ethnomusicology’s always been more complex and far try to grapple with some facet of founding in the early twentieth ranging than that, with scholars existence. Why, for example, are century through the nineteen- from a wide array of backgrounds sociology (the study, perhaps, of eighties at least, it had been a making contributions to our society) and anthropology (the truism that our field operates at literature, and that is even more study of humanity) different the intersection of anthropology true today. -

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303 Instructor: Marilyn Boltz Office: Sharpless 407 Contact Info: 610-896-1235 or [email protected] Office Hours: before class and by appointment Course Description Music is a human universal that has been found throughout history and across different cultures of the world. Why, then, is music so ubiquitous and what functions does it serve? The intent of this course is to examine this question from multiple psychological perspectives. Within a biological framework, it is useful to consider the evolutionary origins of music, its neural substrates, and the development of music processing. The field of cognitive psychology raises questions concerning the relationship between music and language, and music’s ability to communicate emotive meaning that may influence visual processing and body movement. From the perspectives of social and personality psychology, music can be argued to serve a number of social functions that, on a more individual level, contribute to a sense of self and identity. Lastly, musical behavior will be considered in a number of applied contexts that include consumer behavior, music therapy, and the medical environment. Prerequisites: Psychology 100, 200, and at least one advanced 200-level course. Biological Perspectives A. Evolutionary Origins of Music When did music evolve in the overall evolutionary scheme of events and why? Does music serve any adaptive purposes or is it, as some have argued, merely “auditory cheesecake”? What types of evidence allows us to make inferences about the origins of music? Reading: Thompson, W.F. (2009). Origins of Music. In W.F. Thompson, Music, thought, and feeling: Understanding the psychology of music. -

Elements of Sociology of Music in Today's Historical

AD ALTA JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH ELEMENTS OF SOCIOLOGY OF MUSIC IN TODAY’S HISTORICAL MUSICOLOGY AND MUSIC ANALYSIS aKAROLINA KIZIŃSKA national identity, and is not limited to ethnographic methods. Rather, sociomusicologists use a wide range of research methods Adam Mickiewicz University, ul. Szamarzewskiego 89A Poznań, and take a strong interest in observable behavior and musical Poland interactions within the constraints of social structure. e-mail: [email protected] Sociomusicologists are more likely than ethnomusicologists to make use of surveys and economic data, for example, and tend to focus on musical practices in contemporary industrialized Abstract: In this article I try to show the incorporation of the elements of sociology of 6 societies”. Classical musicology, and it’s way of emphasizing music by such disciplines as historical musicology and music analysis. For that explain how sociology of music is understood, and how it is connected to critical historiographic and analytical rather than sociological theory, criticism or aesthetic autonomy. I cite some of the musicologists that wrote approaches to research, is the reason why sociomusicology was about doing analysis in context and broadening the research of musicology (e.g. Jim regarded as a small subdiscipline for a long time. But the Samson, Joseph Kerman). I also present examples of the inclusion of sociology of music into historical musicology and music analysis – the approach of Richard increasing popularity of ethnomusicology and new musicology Taruskin in and Suzanne Cusick. The aim was to clarify some of the recent changes in (as well as the emergence of interdisciplinary field of cultural writing about music, that seem to be closer today to cultural studies than classical studies), created a situation in which sociomusicology is not only musicology. -

Toward a New Comparative Musicology

Analytical Approaches To World Music 2.2 (2013) 148-197 Toward a New Comparative Musicology Patrick E. Savage1 and Steven Brown2 1Department of Musicology, Tokyo University of the Arts 2Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University We propose a return to the forgotten agenda of comparative musicology, one that is updated with the paradigms of modern evolutionary theory and scientific methodology. Ever since the field of comparative musicology became redefined as ethnomusicology in the mid-20th century, its original research agenda has been all but abandoned by musicologists, not least the overarching goal of cross-cultural musical comparison. We outline here five major themes that underlie the re-establishment of comparative musicology: (1) classification, (2) cultural evolution, (3) human history, (4) universals, and (5) biological evolution. Throughout the article, we clarify key ideological, methodological and terminological objections that have been levied against musical comparison. Ultimately, we argue for an inclusive, constructive, and multidisciplinary field that analyzes the world’s musical diversity, from the broadest of generalities to the most culture-specific particulars, with the aim of synthesizing the full range of theoretical perspectives and research methodologies available. Keywords: music, comparative musicology, ethnomusicology, classification, cultural evolution, human history, universals, biological evolution This is a single-spaced version of the article. The official version with page numbers 148-197 can be viewed at http://aawmjournal.com/articles/2013b/Savage_Brown_AAWM_Vol_2_2.pdf. omparative musicology is the academic comparative musicology and its modern-day discipline devoted to the comparative study successor, ethnomusicology, is too complex to of music. It looks at music (broadly defined) review here. -

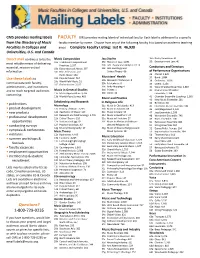

I:\My Drive\Mailing Labels\Mailing Labels

CMS provides mailing labels FACULTY CMS provides mailing labels of individual faculty. Each label is addressed to a specific from the Directory of Music faculty member by name. Choose from any of the following faculty lists based on academic teaching Faculties in Colleges and areas. Complete Faculty Listing: List B: 46,930 Universities, U.S. and Canada. Direct mail continues to be the Music Composition Jazz Studies 35h Radio/Television: 43 10a Traditional Compositional 29a History of Jazz: 1,694 35i Entertainment Law: 40 most reliable means of delivering 29b Jazz Theory and Analysis: 2, Practices: 2,397 114 Conductors and Directors essential, mission‐critical 10b Electroacoustic Music: 397 29c Jazz Sociology and information. 10c Film, Television, and Critical Theory: 66 of Performance Organizations Radio Music: 2 36 Choral: 2,528 80 Musicians' Health 10d Popular Music: 454 37 Band: 1,884 Use these labels to 30a Alexander Technique: 10e World Folk Music: 51 8 38 Orchestra: 1,036 communicate with faculty, 30b Feldenkrais: 0 10f Orchestration: 2,037 39 Opera: 1,259 administrators, and institutions 30c Body Mapping: 0 40 Vocal Chamber Ensemble: 1,084 and to reach targeted audiences Music in General Studies 30d Pilates: 1 41 Instrumental Chamber 30e Other: 10 concerning: 11a Music Appreciation: 3,765 Ensemble: 1,398 11b World Music Survey: 42 Chamber Ensemble Coaching: 1,3 463 Music and Practice 65 43 New Music Ensemble: 261 Scholarship and Research • publications in Religious Life 44 Bell Choir: 86 Musicology 31a Music in Christianity: 413 -

Proceedings, the 57Th Annual Meeting, 1981

PROCEEDINGS THE FIFTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL MEETING National Association of Schools of Music NUMBER 70 APRIL 1982 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC PROCEEDINGS OF THE 57th ANNUAL MEETING Dallas, Texas I98I COPYRIGHT © 1982 ISSN 0190-6615 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF MUSIC 11250 ROGER BACON DRIVE, NO. 5, RESTON, VA. 22090 All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form. CONTENTS Speeches Presented Music, Education, and Music Education Samuel Lipman 1 The Preparation of Professional Musicians—Articulation between Elementary/Secondary and Postsecondary Training: The Role of Competitions Robert Freeman 11 Issues in the Articulation between Elementary/Secondary and Postsecondary Training Kenneth Wendrich 19 Trends and Projections in Music Teacher Placement Charles Lutton 23 Mechanisms for Assisting Young Professionals to Organize Their Approach to the Job Market: What Techniques Should Be Imparted to Graduating Students? Brandon Mehrle 27 The Academy and the Marketplace: Cooperation or Conflict? Joseph W.Polisi 30 "Apples and Oranges:" Office Applications of the Micro Computer." Lowell M. Creitz 34 Microcomputers and Music Learning: The Development of the Illinois State University - Fine Arts Instruction Center, 1977-1981. David L. Shrader and David B. Williams 40 Reaganomics and Arts Legislation Donald Harris 48 Reaganomics and Art Education: Realities, Implications, and Strategies for Survival Frank Tirro 52 Creative Use of Institutional Resources: Summer Programs, Interim Programs, Preparatory Divisions, Radio and Television Programs, and Recordings Ray Robinson 56 Performance Competitions: Relationships to Professional Training and Career Entry Eileen T. Cline 63 Teaching Aesthetics of Music Through Performance Group Experiences David M.Smith 78 An Array of Course Topics for Music in General Education Robert R. -

Utopian Ecomusicologies and Musicking Hornby Island

WHAT IS MUSIC FOR?: UTOPIAN ECOMUSICOLOGIES AND MUSICKING HORNBY ISLAND ANDREW MARK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, CANADA August, 2015 © Andrew Mark 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns making music as a utopian ecological practice, skill, or method of associative communication where participants temporarily move towards idealized relationships between themselves and their environment. Live music making can bring people together in the collective present, creating limited states of unification. We are “taken” by music when utopia is performed and brought to the present. From rehearsal to rehearsal, band to band, year to year, musicking binds entire communities more closely together. I locate strategies for community solidarity like turn-taking, trust-building, gift-exchange, communication, fundraising, partying, education, and conflict resolution as plentiful within musical ensembles in any socially environmentally conscious community. Based upon 10 months of fieldwork and 40 extended interviews, my theoretical assertions are grounded in immersive ethnographic research on Hornby Island, a 12-square-mile Gulf Island between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, Canada. I describe how roughly 1000 Islanders struggle to achieve environmental resilience in a uniquely biodiverse region where fisheries collapsed, logging declined, and second-generation settler farms were replaced with vacation homes in the 20th century. Today, extreme gentrification complicates housing for the island’s vulnerable populations as more than half of island residents live below the poverty line. With demographics that reflect a median age of 62, young individuals, families, and children are squeezed out of the community, unable to reproduce Hornby’s alternative society. -

Cognitive Science and the Cultural Nature of Music

Topics in Cognitive Science 4 (2012) 668–677 Copyright Ó 2012 Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 1756-8757 print / 1756-8765 online DOI: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01216.x Cognitive Science and the Cultural Nature of Music Ian Cross Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge Received 5 September 2010; received in revised form 8 June 2012; accepted 8 June 2012 Abstract The vast majority of experimental studies of music to date have explored music in terms of the processes involved in the perception and cognition of complex sonic patterns that can elicit emotion. This paper argues that this conception of music is at odds both with recent Western musical scholar- ship and with ethnomusicological models, and that it presents a partial and culture-specific represen- tation of what may be a generic human capacity. It argues that the cognitive sciences must actively engage with the problems of exploring music as manifested and conceived in the broad spectrum of world cultures, not only to elucidate the diversity of music in mind but also to identify potential commonalities that could illuminate the relationships between music and other domains of thought and behavior. Keywords: Music; Learning; Processing; Ethnomusicology; Culture 1. The cognitive science and neuroscience of music The study of music learning and processing seems to present a rich set of complex chal- lenges in the auditory domain, drawing on psychoacoustic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuro- scientific approaches. Music appears to manifest itself as complex and time-ordered sequences of sonic events varying in pitch, loudness, and timbre that are capable of eliciting emotion.