Landrake in World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Easter Sessions ............................................................................................................. 64 4. Midsummer Sessions ................................................................................................... 79 5. Summer Assizes ......................................................................................................... 102 6. Michaelmas Sessions.................................................................................................. 125 Royal Cornwall Gazette 6th January 1860 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions opened at 11 o’clock on Tuesday the 3rd instant, at the County Hall, Bodmin, before the following Magistrates: Chairmen: J. JOPE ROGERS, ESQ., (presiding); SIR COLMAN RASHLEIGH, Bart.; C.B. GRAVES SAWLE, Esq. Lord Vivian. Edwin Ley, Esq. Lord Valletort, M.P. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. The Hon. Captain Vivian. W. Horton Davey, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. Stephen Nowell Usticke, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. George Williams, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. R. Gould Lakes, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. Augustus Coryton, Esq. Neville Norway, Esq. Harry Reginald -

Area Food Deliveries Other Support Liskeard Kevin James, Milkman – a Wide Selection of FB Page: Liskeard COVID-19 Food and Essentials Available Too

Area Food deliveries Other Support Liskeard Kevin James, Milkman – A wide selection of FB Page: Liskeard COVID-19 food and essentials available too. – covering Help and Support Liskeard, Looe, Torpoint, Polperro, Bodmin, FB Page: Dobwalls and Saltash, Launceston and everywhere Liskeard Coronavirus Support between: 01579 340 386 Liskeard and Looe Foodbank: Victoria Inn (Pensilva) – Meals on Wheels: 07512 011452 01579 363933 Beddoes Fruit and Veg (Liskeard) – Home deliveries: 01579 363 933 Phillip Warren – Oughs Butchers (Liskeard) – Home deliveries: 07423327218 Spar (Menheniot) – Home deliveries: 01579 342266 Horizon Farm Shop – Groceries and meals delivered (St Cleer/Pensilva etc): 01579 557070 Crows Nest (Meals home delivered): 01579 345930 Liskeard Pet Shops (Deliveries): 01579 347 144 Highwayman (Dobwalls) Meals Home delivered): 01579 320114 Village Greens Mount (deliveries to Warleggan Parish, St Neot and Cardinham) 07815619754 The Fat Frog (Home delivery in 2.5 mile radius of Liskeard): 01579 348818 The Liskeard Tavern (Staff willing to volunteer in their community): 01579 341752 Pensilva Stores (Home Deliveries Pensilva): 01579 362457 Rumours Cafe (Free local delivery Liskeard): 01579 342302 Looe Tredinnick Farm Shop - (Looe and FB: Looe Coronavirus Support surrounding area): 01503 240992 FB: Pelynt COVID community Support Sarahs Taxis (Able to deliver items to home FB: Morval and Widegates for free) 01503 265688 covid 19 support group FB: Polruan isolation support Café Fleur (Meals can be dropped to your car): 01503 265734 Liskeard -

Price £166,911 - Freehold

Price £166,911 - Freehold Dens Meadow, Blunts, Saltash PL12 5FG Offered with no onward chain is this 3 bedroom semi-detached affordable home situated in the hamlet of Blunts. It offers an opportunity for someone looking to purchase their first home or having a housing need with a local connection to the parish.The property is subject to a section 106 please see agents note. The accommodation briefly comprises of Lounge, kitchen/diner, cloakroom, two double bedrooms with one spacious single and bathroom. Outside there are lawned gardens to the front, side and rear enclosed with wooden fencing. The property also benefits from electric radiator heating and hot water via thermal solar panels, uPVC double glazing and hard stand parking for 2 vehicles. Internal viewing is highly recommended. Situation:- First Floor Landing:- Blunts is a hamlet southeast of Quethiock in Access through to the bedrooms and the civil parish of Quethiock in east bathroom. Loft access. Airing cupboard Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is housing the central heating boiler, tank. situated west of the River Lynher valley about 5 miles northwest of Saltash on the Bedroom 1:- 16'9" (5.11m) x 10'8" (3.25m) road from Quethiock village to Landrake. A double bedroom with uPVC double glazed Saltash is a picturesque town that lies just windows to the front elevation enjoying a across the River Tamar from Plymouth and pleasant outlook across the countryside. is often referred to as the "Gateway to Radiator and wardrobe recessed area. Cornwall". The town centre itself provides many shops and the doctors, dentists, Bedroom 2:- 11'0" (3.35m) x 9'7" (2.92m) library and leisure centre are all close by. -

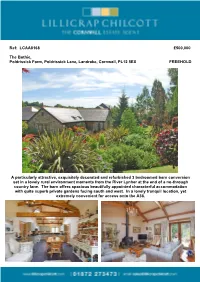

Ref: LCAA8168 £500,000

Ref: LCAA8168 £500,000 The Bothie, Poldrissick Farm, Poldrissick Lane, Landrake, Cornwall, PL12 5EX FREEHOLD A particularly attractive, exquisitely decorated and refurbished 3 bedroomed barn conversion set in a lovely rural environment moments from the River Lynher at the end of a no-through country lane. The barn offers spacious beautifully appointed characterful accommodation with quite superb private gardens facing south and west. In a lovely tranquil location, yet extremely convenient for access onto the A38. 2 Ref: LCAA8168 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION L-shaped entrance hallway, very spacious kitchen/dining room, superb vaulted ceilinged sitting room, 3 double bedrooms (principal en-suite), family bathroom. Outside: beautifully kept private south and west facing gardens. Parking for 3-4 vehicles. DESCRIPTION The Bothie is a very attractive barn conversion with random stone elevations and set in a quite delightful position moments from the River Lynher, in mature south and west facing gardens at the end of a no-through country lane. The accommodation is both spacious and impeccably presented, with much use of high quality materials and provides very comfortable accommodation. From the gravelled driveway the entrance is approached over a slated area which opens onto the L-shaped spacious hallway with skylights. The kitchen/dining room is a particularly impressive entertaining space with large windows overlooking the gardens and access out onto a sun terrace. The kitchen has been beautifully reappointed with superb units and granite worksurfaces and a full suite of integrated appliances. The dining and entertaining area take full advantage of the outlook over the garden and the vaulted ceiling throughout with its beamed ceilings and natural slate floor in the kitchen make this a delightful space. -

Landrake Parish Church

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LANDRAKE PARISH CHURCH We think of the River Tamar as marking the boundary between Cornwall and the rest of England, but back in the time of the Saxons the River Lynher was more of a boundary between Saxon England and the Celts. Villages to the east of the Lynher had Saxon name derivations (eg, -ton) while the majority to the west of the Lynher were Celtic in origin (eg, Tre-). This being the case, the village of Landrake, standing close to the lowest crossing point of the river, was an important route centre. Sites chosen for a church in earlier times were often on top of a hill. Everyone could see it and it would be above all other buildings. It had to be in a position which could easily be reached by local people, and often it was a place of refuge from enemies as well as a place of worship. The earliest reference to the present church in Landrake was in 1018 when King Cnut granted land to Bishop Burwhold for his life and then to pass to the Holy Germanies. This marked the connection with the priory at St Germans, whose monks were responsible for taking the services in Landrake. Landrake is also mentioned in the Exeter edition of the Domesday Book of 1086 which states that there was a wood and wattle church of Saxon origin at Landrake. About 135 churches were built in Cornwall under the Normans but many traces of their work remain unrecognisable today due to enlargement or rebuilding. -

Cornwall. [Kelly S

7 466 GRO CORNWALL. [KELLY S GROCERS & TEA DEALERS-continued. Geary Jn. 15 St. Dominick st. Penzance Hicks & Son, 4 Market st. St. .A.ustell Coath Robert Pill, .Delaware house, George Mrs. Ann, Barn street, Liskeard Hicks J.Sellick,Forest. EastLooe R.S.O Gunnislake, Tavistock George Frank B. Moles worth street, Hicks Miss;\'Iary, Forest. EastLooeR. S. 0 Cobeldick & Co. Fore street, St. Columb Wadebridge R.S.O tHigmanMrs.Emma.,Molesworth street, Major R.S.O George Mrs. Mary, 3 Agar crescent, Wadebridge R.S.O Cock M. A. & Son, to Boscawen Bridge Green Lane, Redruth Hill Henry & Chas. I Taroveor road, & road, Truro George Virilliam Mitchell, Church town, 28 Market place, Penzance Cock James, Leeds Town, Hay le Mullion, Cury Cross Lanes R.S. 0 Hillman Jabez, Calstock, Tavistock Cock Mrs. Jane,gr Green lane, Redrnth Gerrans Mrs. H. Probus R.S.O Hockin Mrs. }<'. Mousehole, Penzance Cock L, C. The Quay, St. Mawes R.S.O Gerry William, Henwood, Linkinhorne, Hockin Fredcrick, Mouschole, Penzance Colenso & Son, Probus R.S.O Callington R.S.O HockinWm.Webb,Markctpl.Camborne Collard W. Tresillian, Probus R.S.O Gerry Wm. A. 1Green market,Penzance Hoc.:king Robt.g4Smithick hill,Falmouth Collett J.St.Just-in-Roseland, Falmouth Gilbart Thoma11 T. Fore st. Camelford Hodge Mrs. Elizabeth, 32 St. Clement Colliver J. G. & Son, Bank street, Gilbert Francis, Pendarves street, Tuck- street Truro St. Columb :Major R.S.O ingmill, Camborne Hodge Mrs. Jane, Probus R.S.O · Cook w·. & Co. Church st. Lannceston Giles Francis Treseder, Polperro R.S.O Hodge R. -

LANDRAKE with ST. ERNEY PARISH COUNCIL

LANDRAKE with ST. ERNEY PARISH COUNCIL Chairman: Cllr G. L. Knowles Clerk: Mr George Trubody 8 Home Park 7 Trefusis Terrace Landrake Millbrook Saltash Torpoint Cornwall PL12 5EW Cornwall PL10 1ED Tel – 01752 851196 Tel – 01752 822323 E-mail – [email protected] th 19 July 2018 Landrake with St.Erney Parish Councillors are summoned to a Parish Council meeting. A meeting of the Parish Council will be held on Tuesday 24th July 2018 in the Geffery Memorial Hall, Landrake, commencing at 7.00pm. The Agenda for the meeting is set out below. George Trubody Clerk to the Parish Council AGENDA OPEN FORUM 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Declarations of Interest on any agenda items 3. Approval of the Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on May 8th 2018 4. Any Matters arising from the Minutes which are not Agenda items: 5. Recreation Field 6. Sir Robert Geffery Memorial Hall 7. Village Playground 8. Village Street Cleaning 9. Neighbourhood Development Plan 10. Future Phone Box use 11. Parish Council Noticeboard replacement 12. Allotments 13. Community Network Highways Scheme 14. St.Erney Highways Signage 15. Footpaths 16. Planning: 16.1 Application PA18/05813 Proposal Certificate of Lawfulness for continued use of building for residential accommodation as a dwelling house to first floor, and residential storage, along with hay/straw to ground floor. Location Land East OF Cuttivett Landrake Cornwall PL12 5AW Applicant Miss Leah White 16.2 Application PA18/05376 Proposal Application for 1) Conversion of garage to habitable room 2) Replacement -

Early History of the Parish of Landrake with St Erney

Early History of the Parish of Landrake with St Erney King Edmund (921-946) had granted Landerhtun (Landrake) to Bishop Burhwold, then the Bishop of the see of St Germans (Cornwall), King Canute confirmed this in a Charter of 1018 instructing that, at the Bishop’s death, Landerhtun was to pass to St Germans Priory which had been founded by Leofric (Livingus) when he was the Abbot of Tavistock. Bishop Burhwold was also granted land for a church at Landrake for his life and then it to be passed to “ the holy Germanies”. Thus the Parish of Landrake became the property of the Priory and remained so until its dissolution in 1539. The monks at St Germans were responsible for taking the services at Landrake and presumably at St Erney as well. Leofric was appointed by King Canute to be Bishop of Crediton (Devon) in 1027 and on the death of his Uncle, Bishop Burhwold, also in 1027, the two dioceses , Cornwall and Devon, were consolidated. In 1046 the see was moved to Exeter where it remained until 1876 when it was split again and the Cornwall see was moved to Truro The church at St Erney was first recorded in 1269 when a vicar was appointed for the churches of Landrake and St Erney in one Parish, it is located on a much earlier site; it probably originated as a chapel belonging to the Priory and upgraded to a church as the population of the area increased due to the expansion of farming and the importance of the route from the sea and the other side of the River Tamar into Cornwall. -

Landrake and St Erney Neighbourhood

LNDP Local Authority Final Version August 2018 This Plan is an outline for how the community of Landrake with St Erney wishes to shape the future development of this beautiful and historic area. Produced by the Landrake with St Erney Neighbourhood Development Plan Steering Group LANDRAKE WITH ST ERNEY NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017-2030 LNDP Local Authority Submission Version February 2018 Contents Page 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 1.1 What is a Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP)? .............................................. 2 2 Background to the Parish ............................................................................. 2 3 Neighbourhood Development Plan ............................................................... 3 3.1 The National Perspective - The Localism Act 2011 ................................................... 3 3.2 The Local Perspective ................................................................................... 3 4 Preparation of the Neighbourhood Development Plan .................................. 3 4.1 Initial Interest .............................................................................................. 3 4.2 Process Chart ............................................................................................... 4 5 Supporting Documents ................................................................................. 6 5.1 Evidence Documents for the LNDP ............................................................... -

LANDRAKE with ST. ERNEY PARISH COUNCIL

LANDRAKE with ST. ERNEY PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held in the Geffery Memorial Hall, Landrake on Tuesday 3rd September 2019 at 7.00 pm. Present – Mr M.Gingell – (Chairman) Mr G.Francis, Mr D.Foote,, Mr M.Webster, Mrs R.Savery Mrs H.Cartledge-Claus 1 member of the public present. OPEN FORUM A member of the public raised the issue of rubbish being put out early next to the playpark with the result of seagulls attacking the rubbish. After discussion the resident agreed to contact Cornwall Councils Environmental Health Team to ask for their advice. 1. Apologies for Absence Miss P.Barton Dr S.Walker, Mr G.Knowles, Mr N.Owen and Cllr J.Foot CC 2. Declarations of Interest on any agenda items None 3. Approval of the Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on July 23rd 2019 It was proposed: G.Francis, seconded: D.Foote and resolved to approve and accept the minutes. 4. Any Matters arising from the Minutes which are not Agenda items None 5. Recreation Field The Chairman reported that the Field was looking smart, but there had been an unfortunate vandalism incident involving white lining paint that had been left near the container. 6. Sir Robert Geffery Memorial Hall Nothing to report 1 7. Village Playground The Chairman reported that vandalism damage that had been sustained to the play matting had now been cleaned up. After discussion it was agreed to place a surveillance warning sign in the Park. The Clerk would produce a draft sign for agreement at the next meeting. -

North Park, Landrake, Saltash, Cornwall Pl12 5Aq Guide Price £550,000

NORTH PARK, LANDRAKE, SALTASH, CORNWALL PL12 5AQ GUIDE PRICE £550,000 LANDRAKE 1 MILE, SALTASH 5 MILES, PLYMOUTH 10 MILES, SEATON BEACH 9 MILES Privately positioned within beautiful established gardens, a detached south facing farmhouse with just over 6 acres of land, offering spacious family accommodation in an enviable rural yet accessible location on the edge of the immensely pretty River Lynher Valley. About 1840 sq ft, 28' Conservatory, 28' Kitchen/Breakfast Room, 17' Sitting Room, 14' Dining Room, 4 Double Bedrooms (1 Ensuite), Family Bathroom, Brick Paved Drive, Rural Views, Pretty Gardens. EPC - F. LOCATION North Park lies in an enviable and remarkably unspoilt part of South East Cornwall within the Lynher Valley Area of Great Landscape Value, deeply rural and yet highly accessible. Landrake (1 mile) provides access to the A38 and offers a renowned primary school (rated "outstanding" by Ofsted), public house, village store/post office and a church. Nearby Treluggan Boatyard (2.5 miles) provides facilities for the yachting fraternity and deep water moorings are available on the River Tamar. A bus route runs through Landrake linking it with Saltash and Plymouth. The surrounding countryside of rolling farmland includes the unspoilt St Erney peninsula to the south, fronting onto the River Lynher, and the beaches of the South Cornish coast at Whitsand Bay are a short drive away. Fine golf courses in the area include the spectacular cliff top course at Portwrinkle and St Mellion International Golf Resort with its additional leisure facilities. Plymouth has a long and historic waterfront together with a mainline railway station (Plymouth to London Paddington 3 hours) and a cross channel ferry port with services to France and Northern Spain.