This Is a Pre-Copyedited, Author-Produced PDF of an Article Accepted for Publication in Notes and Queries Following Peer Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aesthetics of Railing: Troilus and Cressida and Coriolanus

The Aesthetics of Railing:Troilus and Cressida and Coriolanus Maria Teresa Micaela Prendergast The College of Wooster Cet essai explore comment Shakespeare utilise la rhétorique des insultes cruelles et for- tement métaphoriques des débuts de la modernité afin de réaliser une rivalité agressive entre le déclinant idéal aristocratique élisabéthain du sang et du langage épique d’une part, et le théâtre satirique en émergence d’autre part. Ce type de théâtre se justifie en associant le guerrier aristocratique à un corps suintant, efféminé, et malade. Cet essai se concentre en particulier sur les pièces Troilus and Cressida et Coriolanus, qui éta- blissent un fort lien entre la manifestation de maladies internes sur la peau et la perte d’autonomie masculine. Dans Troilus and Cressida, Thersites, incarnant le personnage du fou, domine la pièce avec ses discours vicieux qui transforment sur le plan rhétorique le personnage héroïque de l’aristocrate masculin en une créature abjecte. Parallèlement, Coriolan, en fort contraste avec Thersites, est un guerrier autonome, qui néanmoins sou- tient l’opinion de Thersites que le spectacle théâtral, ainsi que la fréquentation des gens du peuple dégradent les idéaux guerriers aristocratiques. Les deux pièces suggèrent que c’est à travers une langue caustique et scatologique de l’insulte, de pair avec une destruction rhétorique des idéaux de l’aristocratie guerrière, que le théâtre britannique du début du dix-septième siècle remplace une esthétique traditionnelle de l’élite faite de sang héroïque par une célébration de la puissance rhétorique des croûtes et des éruptions cutanées. ike many of his Elizabethan and Jacobean contemporaries, Shakespeare was Lcaught up in the art of railing. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49524-0 — Early Shakespeare, 1588–1594 Edited by Rory Loughnane , Andrew J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49524-0 — Early Shakespeare, 1588–1594 Edited by Rory Loughnane , Andrew J. Power Index More Information Index Achelley, Thomas, 32 canon, 1–3, 5–14, 16, 21, 27, 28, 41, 43, 44–5, 47, 54, Admiral’s Men, 65, 73, 139, 179, 221, 262 60, 61, 64, 78, 87, 102, 103, 121, 135, 168, 169, Aeschylus 190, 200–1, 261, 263, 265–8, 270, 273–4, 277, Oresteia, 139 279, 286, 288 Alleyn, Edward, 65, 209, 211, 221, 232 Chamberlain’s Men, 4, 7, 18, 43, 47, 58, 60–1, 64, Anon 67, 167, 221–2, 233, 262–3, 267, 279, 286 Edmond Ironside, 108 Chapel Children, 179 The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, 275 Chapman, George, 5, 32, 37 King Leir and His Three Daughters, 25, 271, An Humorous Day’s Mirth, 108 273, 275 Monsieur D’Olive, 182 A Knack to Know a Knave, 271, 275 Sir Giles Goosecap, 139 Love and Fortune, 269 Chaucer, Geoffrey, 121–41, 168, 189 Palamon and Arcite, 139 Canterbury Tales, 14, 122, 139 The Second Report of Doctor John Faustus, 163 The Franklin’s Tale, 122, 139 Thomas Lord Cromwell, 108 The Shipman’s Tale, 140 The Troublesome Reigne of King John, 271, Troilus and Criseyde, 139 275 Chettle, Henry, 31, 39 The True Tragedy of Richard the Third, Green’s Groats-worth of Wit, attributed to, 5, 156–7, 271 56, 57 apprenticeship, 31, 141, 223–5, 227, 229, 231 Patient Grissil, with Thomas Dekker and Ariosto, Ludovico William Haughton, 139 Orlando Furioso, 183 Troilus and Cressida, with Thomas Dekker, Aristotle, 136, 138, 275 lost, 139 attribution, 7, 14, 16, 54, 56–7, 58, 60, 77–8, Children of the Queen’s Revels, 35, 221, -

The Faerie Queene

THE AUDIENCE OF THE FAERIE QUEENE MICHAEL MURRIN THE ROMANCE FORM, used by Sidney and Spenser, 1 had an aristocratic origin and continued to advocate aristocratic values in the sixteenth century. Sidney, himself an aristocrat, writes the New Arcadia for such an audience and stresses the duels and tournament-pageants that marked courtly life. 2 Spenser tells Raleigh that he has designed The Faerie Queene "to fashion a gentleman or noble person" (2: 485). One can argue that he thus emulates the courtesy books (see Whigham 1-31) and, like Sidney, pays due attention to duels and jousts. In the words of Richard McCoy, The Faerie Queene celebrates "the chivalric glory of a militant aristocracy" (127). I will argue, however, that the romance form, especially in England, had traditionally appealed to commercial class as well as aristocratic interests. Merchants, Londoners, and also country people read romance, and Spenser himself came from an urban commercial-class background, though at its poorer end. 3 Scholars have long known that the middling sort of people loved romances, though recent critics, more interested in Elizabeth's court, have not discussed the matter.4 Some review of the facts, then, is in order. Before printing, chivalric romance was the favorite fiction for all social levels. 5 In The Canterbury Tales, for example, while the Knight and Squire tell romances, so do the urban Chaucer and the Wife of Bath. The English metrical romance, which Chaucer parodies in "Sir Thopas" and which some have claimed gave Spenser the ground plot for The Faerie Queene, had served a popular audience that could not read French. -

Stores of Guy of Warwick

ABOUT THIS BOOK Conditions and Terms of Use A thousand years ago, fair maidens, gathering around Copyright © Heritage History 2010 their embroidery frames, wove in brilliant colors the story of Some rights reserved valiant deeds wherewith to adorn the walls of bower or wall. This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an And as in and out the shining needles flashed, and the forms of organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history gallant knights, strange beasts, and fearsome giants took shape books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. beneath their flying fingers, the maidens lent an eager ear to The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public some old dame who told, perchance, the wonderous deeds of domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may brave Sir Guy of Warwick, that gallant knight so courteous therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty and so bold. to the author. The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, A thousand years ago, when the feast was over, and the however, are the property of Heritage History and are subject to certain wine-cup passed around the cheerful board and firelight leaped restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the and flickered on teh wall, the minstrel took his harp and sang. integrity of the work, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure He sang, perchance, of how that great Earl, Guy of Warwick, that compromised versions of the work are not widely disseminated. -

CHRISTMAS COMES but ONCE a YEAR by George Zahora

PRESENTS CHRISTMAS COMES BUT ONCE A YEAR by George Zahora Directed by Peter Garino Assistant Director: Brynne Barnard Sound Design & Original Music: George Zahora ________________________ A PROGRAM OF HOLIDAY MUSIC Featuring Hannah Mary Simpson and Camille Cote 25th Anniversary Season December 10, 13, 14, 2019 Elmhurst Public Library Niles-Maine District Library Newberry Library THE SHAKESPEARE PROJECT OF CHICAGO IS PROUD TO * Actors appearing in this performance are members of Actors' Equity ANNOUNCE the lineup for our 25th Anniversary Season. “Hamlet” by Association, the union of professional actors and stage managers. William Shakespeare, directed by J.R. Sullivan (Oct. 11-17, 2019); “Richard III” by William Shakespeare, directed by Peter Garino (Jan. 10- www.shakespeareprojectchicago.org 17, 2020); “Romeo and Juliet” by William Shakespeare, directed by P.O. Box 25126 Michelle Shupe (Feb. 21-27, 2020); “Measure for Measure” by William Chicago, Illinois 60625 Shakespeare, directed by Erin Sloan (May 15-21, 2020). For venues and 773-710-2718 show times, visit: www.shakespeareprojectchicago.org The Shakespeare Project gratefully acknowledges all of the generous contributions made by its valued patrons over the past 24 years. With heartfelt thanks, we recognize contributors to our 2019-2020 season: Ameer Ali, Catherine Alterio, Anonymous, Charles Berglund, Henry Bernstein, Bindy Bitterman, Albertine N. Burget, Alice D. Blount, Lilian F. Braden, Joan Bransfield, An Shih Cheng, Ronald & Earlier this season… Gail Denham, Linda Dienberg, A. Carla Drije, Joyce Dugan, Janet M. Erickson, Jacqueline Fitzgerald, Holly & Brian Forgue, James & Martha Fritts, Gerald Ginsburg, Charlotte Glashagel, Scott Gordon & Amy Cuthbert, Barbara Hayler, Ora M. Jones, Susan Spaford Lane, Carol Lewis, David R. -

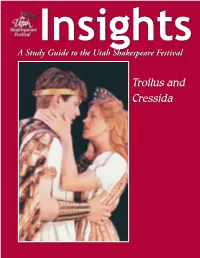

Troilus and Cressida the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Troilus and Cressida The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Cameron McNary (left) and Tyler Layton in Troilus and Cressida, 1999. Contents TroilusInformation and on William Cressida Shakespeare Shakespeare: Words, Words, Words 4 Not of an Age, but for All Mankind 6 Elizabeth’s England 8 History Is Written by the Victors 10 Mr. Shakespeare, I Presume 11 A Nest of Singing Birds 12 Actors in Shakespeare’s Day 14 Audience: A Very Motley Crowd 16 Shakespeare Snapshots 18 Ghosts, Witches, and Shakespeare 20 What They Wore 22 Information on the Play Synopsis 23 Characters 24 Scholarly Articles on the Play An “Iliad” Play 26 Where Are the Heroes and Lovers? 28 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Shakespeare: Words, Words, Words By S. -

Plague, Print and Providence in Early Seventeenth Century London Philip

Plague, Print and Providence in Early Seventeenth Century London Philip Wootton 28000852 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed…….……………P. Wootton………………………………………………... Date …………………18/09/13……………………..…………………………... 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MTh Church History…………………………………................. Signed …………P. Wootton………………………………………………………. Date …………….18/09/13…………………………………………..…………... 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed candidate: ...… P. Wootton .………………………….………………. Date: …………………… 18/09/13………………….………………………. 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository Signed (candidate)……P. Wootton…………………….………….…………... Date………………18/09/13……………….…………….…………….. Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: ………………………………………………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………………………………………………... 2 Plague and Providence in Popular Print in Early Seventeenth Century London AIM: To consider how contemporary understanding of divine providence is reflected in and expressed through selected popular printed material concerning outbreaks of plague in early seventeenth century London, with particular reference to the pamphlets of Thomas Dekker. Contents Abstract Summary page 4 Note on the Location of Sources page 5 Abbreviations page 5 1. Introduction page 6 2. Plague Pamphlets and Historiography page 8 2.1 Characterising the Church of England, c.1600 page 8 2.2 Cheap Print and Popular Belief page 11 2.3 Accessibility of Plague Pamphlets page 13 2.4 Currents of Providentialism page 15 3. -

Reading Across Languages in Medieval Britain by Jamie Ann Deangelis a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requ

Reading Across Languages in Medieval Britain By Jamie Ann DeAngelis A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jennifer Miller, Chair Professor Joseph Duggan Professor Maura Nolan Professor Annalee Rejhon Spring 2012 Reading Across Languages in Medieval Britain © 2012 by Jamie Ann DeAngelis Abstract Reading Across Languages in Medieval Britain by Jamie Ann DeAngelis Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Jennifer Miller, Chair Reading Across Languages in Medieval Britain presents historical, textual, and codicological evidence to situate thirteenth- and fourteenth-century vernacular-to- vernacular translations in a reading milieu characterized by code-switching and “reading across languages.” This study presents the need for—and develops and uses—a new methodological approach that reconsiders the function of translation in this multilingual, multi-directional reading context. A large corpus of late thirteenth- through early fourteenth-century vernacular literature in Britain, in both English and Welsh, was derived from French language originals from previous centuries. These texts include mainly romances and chansons de geste, and evidence suggests that they were produced at the same time, and for the same audience, as later redactions of the texts in the original language. This evidence gives rise to the main question that drives this dissertation: what was the function of translation in a reading milieu in which translations and originals shared the same audience? Because a large number of the earliest or sole surviving translations into English from French language originals appear in Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, Advocates’ MS 19.2.1 (the Auchinleck Manuscript), my study focuses on the translations preserved in this manuscript. -

The Guy of Warwick Mazer

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Sweetinburgh, S. (2015) A tale of two mazers: negotiating relationships at Kentish medieval hospitals'. Archaeologia Cantiana, 136. Link to official URL (if available): This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] A TALE OF TWO MAZERS: NEGOTIATING DONOR/RECIPIENT RELATIONSHIPS AT KENTISH MEDIEVAL HOSPITALS SHEILA SWEETINBURGH For a journal that derives its articles from both archaeologists and historians, it may be especially appropriate to consider an investigation of two medieval objects that are specifically linked to Kent, and can still be found in two of the county’s museums. Furthermore, the study of material culture and what it can reveal about the past has grown in popularity over recent decades, both within academia and what is sometimes labelled ‘popular’ or ‘public’ history. In addition, the cross-fertilization of ideas among archaeologists, art historians and cultural historians has been enhanced by the ideas of social anthropologists and historical geographers.1 These approaches can be extremely fruitful when examining different social groups outside the elite; and among the areas of investigation that has benefitted is the study of gift-giving, including an exploration of the gift itself. The classic text remains Marcel Mauss’ The Gift, but valuable recent scholarship includes Arjun Appaduria’s The Social Life of Things and Natalie Davis’ The Gift.2 As well as exploring what might be seen as the final result, the acquisition of an object, there has been a realisation that perhaps even more noteworthy is the process whereby the gift(s) moves to its new owner(s). -

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 the OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The Oxfordian is the peer-reviewed journal of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, a non-profit educational organization that conducts research and publication on the Early Modern period, William Shakespeare and the authorship of Shakespeare’s works. Founded in 1998, the journal offers research articles, essays and book reviews by academicians and independent scholars, and is published annually during the autumn. Writers interested in being published in The Oxfordian should review our publication guidelines at the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/the-oxfordian/ Our postal mailing address is: The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship PO Box 66083 Auburndale, MA 02466 USA Queries may be directed to the editor, Gary Goldstein, at [email protected] Back issues of The Oxfordian may be obtained by writing to: [email protected] 2 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 Acknowledgements Editorial Board Justin Borrow Ramon Jiménez Don Rubin James Boyd Vanessa Lops Richard Waugaman Charles Boynton Robert Meyers Bryan Wildenthal Lucinda S. Foulke Christopher Pannell Wally Hurst Tom Regnier Editor: Gary Goldstein Proofreading: James Boyd, Charles Boynton, Vanessa Lops, Alex McNeil and Tom Regnier. Graphics Design & Image Production: Lucinda S. Foulke Permission Acknowledgements Illustrations used in this issue are in the public domain, unless otherwise noted. The article by Gary Goldstein was first published by the online journal Critical Stages (critical-stages.org) as part of a special issue on the Shakespeare authorship question in Winter 2018 (CS 18), edited by Don Rubin. It is reprinted in The Oxfordian with the permission of Critical Stages Journal. -

Shakespeare, Jonson, and the Invention of the Author

11 Donaldson 1573 11/10/07 15:05 Page 319 SHAKESPEARE LECTURE Shakespeare, Jonson, and the Invention of the Author IAN DONALDSON Fellow of the Academy THE LIVES AND CAREERS OF SHAKESPEARE and Ben Jonson, the two supreme writers of early modern England, were intricately and curiously interwoven. Eight years Shakespeare’s junior, Jonson emerged in the late 1590s as a writer of remarkable gifts, and Shakespeare’s greatest theatri- cal rival since the death of Christopher Marlowe. Shakespeare played a leading role in the comedy that first brought Jonson to public promi- nence, Every Man In His Humour, having earlier decisively intervened— so his eighteenth-century editor, Nicholas Rowe, relates—to ensure that the play was performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who had ini- tially rejected the manuscript.1 Shakespeare’s name appears alongside that of Richard Burbage in the list of ‘principal tragedians’ from the same company who performed in Jonson’s Sejanus in 1603, and it has been con- jectured that he and Jonson may even have written this play together.2 During the years of their maturity, the two men continued to observe Read at the Academy 25 April 2006. 1 The Works of Mr William Shakespeare, ed. Nicholas Rowe, 6 vols. (London, printed for Jacob Tonson, 1709), I, pp. xii–xiii. On the reliability of Rowe’s testimony, see Samuel Schoenbaum, Shakespeare’s Lives (Oxford, 1970), pp. 19–35. 2 The list is appended to the folio text of the play, published in 1616. For the suggestion that Shakespeare worked with Jonson on the composition of Sejanus, see Anne Barton, Ben Jonson: Dramatist (Cambridge, 1984), pp. -

Guy of Warwick

Guy of Warwick anon a Middle English romance the second or fifteenth century version, retelling the early-thirteenth century Anglo-Norman romance Gui de Warewic Translated and retold in Modern English prose by Richard Scott-Robinson This story has been translated and retold from the Middle English verse romance Guy of Warwick (itself a translation of an early-thir- teenth century Anglo-Norman French romance) found in Cam- bridge University Library MS Ff. 2.38, edited by J Zupitza for the Early English Text Society, Extra Series 25 and 26, 1875-6. Copyright © Richard Scott-Robinson, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this document may be repro- duced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. The download of a single copy for personal use, or for teaching purposes, does not require permission. [email protected] Guy of Warwick anon the second or fifteenth century version Sythe þe tyme þat god was borne · and Crystendome was set and sworne · mane aventewres hathe befalle · that yet be not knowen alle ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������· Therfore schulde men mekely herke · and thynke gode allwey to wyrke · and take ensawmpull be wyse men – Since the time that God was born and Christendom established, many adventures have taken place, not all of which are known about yet. Men should therefore listen closely and be prepared to learn from the wise men who have gone before them, for their marvellous adventures, their honesty, their suffering and their struggles have all been recorded.