Thinking Beyond Today’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultation Statement

Maidstone Borough Council Affordable and Local Needs Housing Supplementary Planning Document Consultation Statement 21st August 2019 1 Maidstone Borough Council - Consultation Statement 1.1 Maidstone Borough Council (MBC) has recently adopted its Local Plan (October 2017) and this includes a commitment to produce an Affordable and Local Needs Housing Supplementary Planning Document (the SPD). 1.2 Adams Integra have been instructed to compile an SPD which is intended to facilitate negotiations and provide certainty for landowners, lenders, housebuilders and Registered Providers regarding MBC’s expectations for affordable and local needs housing provision in specific schemes. 1.3 The purpose of this Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) is to provide advice on how the Council’s Local Plan housing policies are to be implemented. 1.4 In order to facilitate the preparation of the SPD we (Adams Integra) consulted with the following persons and organisations: David Banfield Redrow Homes Barry Chamberlain Wealden Homes Tim Daniels Millwood Designer Homes Paul Dawson Fernham Homes Rosa Etherington Countryside Properties PLC Chris Lilley Redrow Homes Chris Loughead Crest Nicholson Iain McPherson Countryside Properties PLC Stuart Mitchell Chartway Group Chris Moore Bellway Guy Osborne Country House Developments Kathy Putnam Chartway Group James Stevens Home Builders Federation Julian Wilkinson BDW Homes Kerry Kyriacou Optivo Adetokunbo Adeyeloja Golding Homes Sarah Paxton Maidstone Housing Trust Joe Scullion Gravesend Churches Housing Association Gareth Crawford Homes Group Mike Finch Hyde HA Russell Drury Moat HA Keiran O'Leary Orbit HA Chris Cheesman Clarion Housing Micheal Neeh Sanctuary HA Colin Lissenden Town and Country West Kent HA Guy Osbourne Country House Homes Katherine Putnam Chartway Group Annabel McKie Golding Homes Councillors at Maidstone Maidstone Borough Council Borough Council 2 Maidstone Borough Council - Consultation Statement 1.5 We sent out separate questionnaires to Housing Associations and Developers which have been appended to this statement. -

Parker Review

Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership An update report from The Parker Review Sir John Parker The Parker Review Committee 5 February 2020 Principal Sponsor Members of the Steering Committee Chair: Sir John Parker GBE, FREng Co-Chair: David Tyler Contents Members: Dr Doyin Atewologun Sanjay Bhandari Helen Mahy CBE Foreword by Sir John Parker 2 Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE Foreword by the Secretary of State 6 Trevor Phillips OBE Message from EY 8 Tom Shropshire Vision and Mission Statement 10 Yvonne Thompson CBE Professor Susan Vinnicombe CBE Current Profile of FTSE 350 Boards 14 Matthew Percival FRC/Cranfield Research on Ethnic Diversity Reporting 36 Arun Batra OBE Parker Review Recommendations 58 Bilal Raja Kirstie Wright Company Success Stories 62 Closing Word from Sir Jon Thompson 65 Observers Biographies 66 Sanu de Lima, Itiola Durojaiye, Katie Leinweber Appendix — The Directors’ Resource Toolkit 72 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Thanks to our contributors during the year and to this report Oliver Cover Alex Diggins Neil Golborne Orla Pettigrew Sonam Patel Zaheer Ahmad MBE Rachel Sadka Simon Feeke Key advisors and contributors to this report: Simon Manterfield Dr Manjari Prashar Dr Fatima Tresh Latika Shah ® At the heart of our success lies the performance 2. Recognising the changes and growing talent of our many great companies, many of them listed pool of ethnically diverse candidates in our in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250. There is no doubt home and overseas markets which will influence that one reason we have been able to punch recruitment patterns for years to come above our weight as a medium-sized country is the talent and inventiveness of our business leaders Whilst we have made great strides in bringing and our skilled people. -

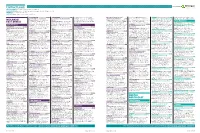

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. NORTHAMPTON £3.7M CHESTERFIELD £1M Detail Plans Granted for 2 luxury houses The Coppice Primary School, 50 County Council Agent: A A Design Ltd, GRIMSBY £1M Studios, Trafalgar Street, Newcastle-Upon- Land Off, Alibone Close Moulton Recreation Ground, North Side New Client: Michael Howard Homes Developer: Shawhurst Lane Hollywood £1.7m Aizlewood Road, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, Grimsby Leisure Centre, Cromwell Road Tyne, Tyne & Wear, NE1 2LA Tel: 0191 2611258 MIDLANDS/ Planning authority: Daventry Job: Outline Tupton Bullworthy Shallish LLP, 3 Quayside Place, Planning authority: Bromsgrove Job: Detail S8 0YX Contractor: William Davis Ltd, Forest Planning authority: North East Lincolnshire Plans Granted for 16 elderly person Planning authority: North East Derbyshire Quayside, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 1FA Tel: Plans Granted for school (extension) Client: Field, Forest Road, Loughborough, Job: Detailed Plans Submitted for leisure Plans Approved EAST ANGLIA bungalows Client: Gayton Retirement Fund Job: Detail Plans Granted for 4 changing 01394 384 736 The Coppice Primary School Agent: PR Leicestershire, LE11 3NS Tel: 01509 231181 centre Client: North East Lincolnshire BILLINGHAM £0.57M & Beechwood Trusteeship & Administration rooms pavilion -

49 P51 AO1 Hot Noms.Qxp 04/12/2007 17:23 Page 51

49 p51 AO1 Hot noms.qxp 04/12/2007 17:23 Page 51 www.propertyweek.com Analysis + opinion – Hot 100 51 07.12.07 ROLL OF HONOUR The following 527 rising stars were all nominated by readers, but did not receive enough votes to make it on to the Hot 100 list. However, we have decided to publish all of their names to recognise and reward their individual achievements Ab Shome, RBS Caroline McDade, Drivers Jonas Douglas Higgins Ian Webster, Colliers CRE Adam Buchler, Buchler Barnett Celine Donnet, Cohen & Steers Duncan Walker, Helical Bar Ian Webster, Savills Adam Oliver, Coleman Bennett Charles Archer, Colliers CRE Edward Offenbach, DTZ James Abrahms, Allsop Adam Poyner, Colliers CRE Charles Bull, DTZ Corporate Finance Edward Siddall-Jones, Nattrass Giles James Ackroyd, Colliers CRE Adam Robson, Drivers Jonas Charles Ferguson Davie, Moorfield Group Edward Towers James Bain, Mollison Adam Varley, Lambert Smith Hampton Charles Kearney, Gerry O’Connor Elizabeth Higgins, Drivers Jonas James Baker, Nice Investments Adam Winton, Kaupthing Estate Agents Elliot Robertson, Manorlane James Cobbold, Colliers CRE Agnes Peters, Drivers Jonas Charlie Archer, Colliers CRE Emilia Keladitis, DTZ Corporate Finance James Ebel, Harper Dennis Hobbs Akhtar Alibhai, Colliers CRE Charlie Barke, Cushman & Wakefield Emma Crowley, Jones Lang LaSalle James Feilden, GVA Grimley Alan Gardener, Jones Lang LaSalle Charlie Bezzant, Reed Smith Richards Butler Emma Wilson, Urban Splash James Goymour, Edward Symmons Alan Hegarty, Bennett Property Charlote Fourmont, Drivers Jonas -

Marten & Co / Quoted Data Word Template

Monthly roundup | Real estate October 2019 Winners and losers in September Best performing companies in price terms in Sept Worst performing companies in price terms in Sept (%) (%) Capital & Regional 37.9 Countrywide (11.7) Hammerson 24.9 Town Centre Securities (7.2) NewRiver REIT 19.1 Aseana Properties (5.1) Inland Homes 15.8 Harworth Group (4.3) Capital & Counties Properties 14.8 Ediston Property Investment Company (4.0) British Land 14.7 GRIT Real Estate Income Group (3.7) Workspace Group 13.2 Daejan Holdings (3.5) Countryside Properties 12.3 Primary Health Properties (2.9) Triple Point Social Housing REIT 11.7 Big Yellow Group (2.9) U and I Group 11.1 Conygar Investment Company (2.6) Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co Capital & Regional share price YTD The month of Countrywide share price YTD On the flip side, the September was a UK’s biggest estate 40 12 bumper month for agent group, 30 many property 8 Countrywide, which 20 companies’ share also owns a 4 10 price, dominated by commercial real 0 retail focused 0 estate consultancy, Jan FebMar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Jan FebMar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep companies, who in was the worst Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co general have taken a Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co performing in hammering over the September. It is the past 18 months or so. Top of the list was Capital & Regional. second month in a row that it has been in the bottom 10 and Shares in the shopping centre landlord bounced after it in the year to date it is beaten only by Intu Properties as the announced it was in talks with South African REIT worst performing listed property company, losing 53.5%. -

LOCAL CENTRE SITE Marham Park, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP32 6TN

DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE LOCAL CENTRE SITE Marham Park, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP32 6TN Key Highlights • Opportunity to purchase a 0.3 acre Local • For sale Centre Site in the heart of a 1,070 home • Occupations on site to date total 201 development (as of October 2019) • Fully serviced site offered with Vacant Possession SAVILLS CAMBRIDGE Unex House, 132-134 Hills Road Cambridge, CB2 8PA +44 (0) 1223 347 000 savills.co.uk Location The overall development site is located south of the junction All Section 106 Agreement obligations will be met by between A1101 and B1106 (Tut Hill), north of the Bury St Countryside Properties (UK) Ltd or the purchasers of Edmunds Golf Club, approximately 1.7 miles north west of parcels of land for residential development. The Local Centre Bury St Edmunds town centre and adjacent to the village of therefore is offered free of any Section 106 obligations. Fornham All Saints to the north. Junction 42 of the A14 dual Further details can be found under Planning Reference carriageway is located to the south west. Number: DC/13/0932/HYB on the St Edmundsbury Borough The Local Centre site sits centrally within the wider Marham Council website or a copy of the Decision Notice and Section Park development. The parcel is directly located alongside 106 Agreement can be made available upon request. Parcel H, a central public square and has direct access off Marham Parkway and Sandlands Drive. Services Description All services are located within Sandlands Drive. The site is fully serviced with Gas, Electric and Water. -

Marten & Co / Quoted Data Word Template

Monthly roundup | Real estate August 2020 Kindly sponsored by Aberdeen Standard Investments Winners and losers in July Best performing companies in price terms in July Worst performing companies in price terms in July (%) (%) AEW UK REIT 18.9 Hammerson (20.0) UK Commercial Property REIT 14.9 Countryside Properties (14.4) Schroder REIT 14.5 U and I Group (14.0) Empiric Student Property 11.4 Real Estate Investors (13.4) Palace Capital 10.6 Tritax EuroBox (11.8) LondonMetric Property 9.7 St Modwen Properties (10.9) Triple Point Social Housing REIT 9.2 Drum Income Plus REIT (10.0) RDI REIT 8.5 Alternative Income REIT (8.4) SEGRO 8.3 Panther Securities (8.2) CLS Holdings 5.5 BMO Commercial Property Trust (7.1) Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co. AEW UK REIT share price YTD A number of REITs Hammerson share price YTD Retail landlord and property Hammerson continued 110 companies saw big 300 to see its share price 95 255 share price gains 210 fall during July and has 80 over the month of 165 now lost 79.2% of its 120 65 July as covid-19 value in the year to 75 50 restrictions started to 30 date – the worst in the Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul ease across the UK Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul real estate sector. The Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co and greater Source: Bloomberg, Marten & Co company, which owns economic stimulus shopping centres, retail was revealed. The biggest mover was AEW UK REIT. -

SL ASI UK Real Estate Share Pension Fund Invests Primarily in the ASI UK Real Estate Share Fund

Q1 SL ASI UK Real Estate Share 2021 Pension Fund 31 March 2021 This document is intended for use by individuals who are familiar with investment terminology. Please contact your financial adviser if you need an explanation of the terms used. The SL ASI UK Real Estate Share Pension Fund invests primarily in the ASI UK Real Estate Share Fund. The aim of Pension the ASI UK Real Estate Share Fund is summarised below. Investment Fund To generate income and some growth over the long term (5 years or more) by investing in UK property-related equities (company shares) including listed closed ended real estate investment trusts (REITs). The value of any investment can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed – you may get back less than you pay Property Fund in. For further information on the ASI UK Real Estate Share Fund, please refer to the fund manager fact sheet, link provided below. Standard Life does not control or take any responsibility for the content of this. Quarterly ASI UK Real Estate Share - Fund Factsheet http://webfund6.financialexpress.net/clients/StandardLife/FS.aspx?Code=KV58&Date=01/03/2021 Underlying Fund Launch Date October 1990 Standard Life Launch Date April 2006 Underlying Fund Size (31/03/2021) £344.4m Standard Life Fund Size (31/03/2021) £20.2m Underlying Fund Manager Romney Fox, Standard Life Fund Code 2N Sanjeet Mangat Volatility Rating (0-7) 7 The investment performance you will experience from investing in the Standard Life version of the fund will vary from the investment performance you would experience from investing in the underlying fund directly. -

Sustainability Report 2020.Pdf

Places People Love Countryside Properties PLC Sustainability Report 2020 Countryside Properties PLC / Sustainability Report 2020 1 2020 PERFORMANCE AND HIGHLIGHTS Total Homes Completed Homes for the Private Rented Sector Completed Affordable Homes Completed Adjusted Revenue (£m) 4,053 908 1,691 £988.8m 20 4,053 20 908 20 1,691 20 £988.8m 19 5,733 19 1,377 19 2,179 19 £1,422.8m Financial year Financial year 18 4,295 Financial year 18 816 18 1,503 Financial year 18 £1,229.5m Adjusted Operating Margin (%) Land Bank # Plots Annual Injury Incidence Rate (AIIR) Amount of Communities Fund Spent in 2020 (£) 5.5 53,118 224 £760,095.12 20 5.5% 20 53,118 20 224 19 16.5% 19 49,000 19 227 Financial year 18 17.2% Financial year 18 43,523 Financial year 18 162 Countryside Properties PLC / Sustainability Report 2020 2 2020 performance and highlights continued Total Waste Produced (tonnes) Total Site Waste Diverted from Landfill (%) GHG – Scope 1 (tCO2e) GHG – Scope 2 (tCO2e) 45,492 98.5 5,770 1,906 20 45,492 20 98.5 20 5,770 20 1,906 19 42,352 19 97.5 19 5,391 19 1,863 Financial year 18 31,042 Financial year 18 99.4 Financial year 18 4,560 Financial year 18 1,405 GHG – Fleet (tCO2e) Sites with Biodiversity Action Plans (%) NHBC Recommend a Friend Score (%) Section 106 Spend in the Year (£) 1,791 42 90.6 £34,414,290 20 1,791 20 42 20 90.6 19 1,827 19 39 19 92.5 Financial year 18 1,656 Financial year 18 37 Financial year 18 84.6 Countryside Properties PLC / Sustainability Report 2020 3 Countryside at a glance Partnerships WHAT SETS Housebuilding US APART Since 2000 we have won 385 awards for design and sustainability excellence. -

Abbey ABBY Household Goods and Home Construction — GBP 16 at Close 29 April 2021

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance Abbey ABBY Household Goods and Home Construction — GBP 16 at close 29 April 2021 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 29-Apr-2021 29-Apr-2021 29-Apr-2021 16 200 140 1D WTD MTD YTD Absolute 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.2 Rel.Sector 0.5 1.3 -4.3 -99.4 15 130 Rel.Market 0.1 -0.3 -3.7 -4.6 150 14 120 VALUATION 100 Trailing Relative Price Relative 13 Price Relative 110 PE 14.8 Absolute Price (local (local currency) AbsolutePrice 50 EV/EBITDA 7.5 12 100 PB 1.0 PCF -ve 11 0 90 Div Yield 0.0 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Price/Sales 2.2 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity 0.0 100 100 90 Div Payout 7.9 90 90 80 ROE 7.1 80 80 70 70 70 Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 The Company's principal activities are building and 40 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) property development, plant hire and property rental. 30 30 30 20 20 20 10 10 10 RSI (Relative to FTSE UKFTSE All to RSI (Relative RSI (Relative to FTSE UKFTSE All to RSI (Relative 0 0 0 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Apr-2020 Jun-2020 Aug-2020 Oct-2020 Dec-2020 Feb-2021 Past performance is no guarantee of future results. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS DOCUMENT IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE (1) QUALIFIED INSTITUTIONAL BUYERS (“QIBS”) AS DEFINED IN RULE 144A UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE “US SECURITIES ACT”), OR (2) OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES IN COMPLIANCE WITH REGULATION S UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT (“REGULATION S”). IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the document following this page (the “ Document ”), and you are therefore advised to read this notice carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Document. In accessing the Document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from Countryside Properties plc (the “ Company ”), J.P. Morgan Securities plc, which conducts its investment banking activities as J.P. Morgan Cazenove (“ J.P. Morgan Cazenove ”), Barclays Bank PLC (“ Barclays ”), Numis Securities Limited (“ Numis ”) and Peel Hunt LLP (“ Peel Hunt ”) (J.P. Morgan Cazenove, Barclays, Numis and Peel Hunt each a “ Bank ” and collectively, the “ Banks ”) as a result of such access. IF YOU ARE NOT THE INTENDED RECIPIENT OF THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION, PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE OR COPY THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION, BUT INSTEAD DELETE AND DESTROY ALL COPIES OF THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES DESCRIBED HEREIN HAVE NOT BEEN AND WILL NOT BE REGISTERED UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND SUCH SECURITIES MAY NOT BE OFFERED, SOLD, PLEDGED OR OTHERWISE TRANSFERRED DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY IN, INTO OR WITHIN THE UNITED STATES, EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE US SECURITIES ACT AND APPLICABLE STATE SECURITIES LAWS. -

JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund Monthly Update

Professional Investors Only JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund Monthly Bulletin: January 2019 Active sector bets for the month ending 31 December 2018: Top five Sector % of Portfolio % of FTSE All-Share Active % Financial Services 9.39 3.07 +6.32 Banks 16.38 10.76 +5.62 Mining 10.40 6.55 +3.85 Oil & Gas Producers 17.59 13.99 +3.60 Construction & Materials 5.06 1.53 +3.53 Bottom five Sector % of Portfolio % of FTSE All-Share Active % Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology 0.00 7.54 -7.54 Equity Investment Instruments 0.33 5.11 -4.78 Tobacco 0.00 3.80 -3.80 Beverages 0.00 3.60 -3.60 Personal Goods 0.00 2.53 -2.53 Active stock bets for the month ending 31 December 2018: Top ten Stock % of Portfolio % of FTSE All-Share Active % Aviva 3.55 0.70 +2.85 Barclays 3.99 1.22 +2.77 BP 7.37 4.62 +2.75 DS Smith 2.91 0.18 +2.73 ITV 2.92 0.22 +2.70 Glencore 4.16 1.58 +2.58 Standard Life Aberdeen 2.85 0.31 +2.54 Lloyds Banking Group 4.27 1.76 +2.51 Phoenix Group 2.31 0.14 +2.17 Vodafone Group 4.04 1.95 +2.09 Bottom five Stock % of Portfolio % of FTSE All-Share Active % AstraZeneca 0.00 3.55 -3.55 GlaxoSmithKline 0.00 3.46 -3.46 Diageo 0.00 3.22 -3.22 British American Tobacco 0.00 2.72 -2.72 Unilever 0.00 2.14 -2.14 JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund: January 2019 Performance to 31 December 2018 (%): 1 month Year to date Since inception Fund size JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund – -4.76 -13.19 240.20 £3,222mn A Acc GBP Lipper UK Equity Income mean* -4.43 -10.91 146.24 FTSE All-Share TR Index (12pm -3.93 -9.06 157.23 adjusted) Discrete 12-month performance (%) to: 31.12.18 29.12.17 30.12.16 31.12.15 31.12.14 JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund – A -13.19 18.11 16.79 0.96 1.11 Acc GBP FTSE All-Share TR Index (12pm -9.06 13.10 16.05 1.25 0.93 adjusted) Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.