Fossil Charcoal in Late Devonian Marine Shales As an Indicator of Expanding Terrestrial Ecosystems, Fire, and Atmospheric Change Susan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carboniferous Bowland Shale Gas Study: Geology and Resource Estimation

THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation i © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Disclaimer This report is for information only. It does not constitute legal, technical or professional advice. The Department of Energy and Climate Change does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss or damage of any nature, however caused, which may be sustained as a result of reliance upon the information contained in this report. All material is copyright. It may be produced in whole or in part subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source, but should not be included in any commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the written permission of the Department of Energy and Climate Change. Suggested citation: Andrews, I.J. 2013. The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation. British Geological Survey for Department of Energy and Climate Change, London, UK. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to: Toni Harvey Senior Geoscientist - UK Onshore Email: [email protected] ii © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Foreword This report has been produced under contract by the British Geological Survey (BGS). It is based on a recent analysis, together with published data and interpretations. Additional information is available at the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) website. https://www.gov.uk/oil-and-gas-onshore-exploration-and-production. This includes licensing regulations, maps, monthly production figures, basic well data and where to view and purchase data. -

Two Stages of Late Carboniferous to Triassic Magmatism in the Strandja

Geological Magazine Two stages of Late Carboniferous to Triassic www.cambridge.org/geo magmatism in the Strandja Zone of Bulgaria and Turkey ł ń 1,2 3 1 1 Original Article Anna Sa aci ska , Ianko Gerdjikov , Ashley Gumsley , Krzysztof Szopa , David Chew4, Aleksandra Gawęda1 and Izabela Kocjan2 Cite this article: Sałacińska A, Gerdjikov I, Gumsley A, Szopa K, Chew D, Gawęda A, and 1Institute of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Silesia in Katowice, Będzińska 60, 41-200 Kocjan I. Two stages of Late Carboniferous to 2 3 Triassic magmatism in the Strandja Zone of Sosnowiec, Poland; Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland; Faculty of ‘ ’ Bulgaria and Turkey. Geological Magazine Geology and Geography, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski , 15 Tzar Osvoboditel Blvd., 1504 Sofia, Bulgaria 4 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756821000650 and Department of Geology, School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland Received: 9 February 2021 Abstract Revised: 3 June 2021 Accepted: 8 June 2021 Although Variscan terranes have been documented from the Balkans to the Caucasus, the southeastern portion of the Variscan Belt is not well understood. The Strandja Zone along Keywords: the border between Bulgaria and Turkey encompasses one such terrane linking the Strandja Zone; Sakar unit; U–Pb zircon dating; Izvorovo Pluton Balkanides and the Pontides. However, the evolution of this terrane, and the Late Carboniferous to Triassic granitoids within it, is poorly resolved. Here we present laser ablation Author for correspondence: – inductively coupled plasma – mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) U–Pb zircon ages, coupled ł ń Anna Sa aci ska, with petrography and geochemistry from the Izvorovo Pluton within the Sakar Unit Email: [email protected] (Strandja Zone). -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

Devonian and Carboniferous Stratigraphical Correlation and Interpretation in the Central North Sea, Quadrants 25 – 44

CR/16/032; Final Last modified: 2016/05/29 11:43 Devonian and Carboniferous stratigraphical correlation and interpretation in the Orcadian area, Central North Sea, Quadrants 7 - 22 Energy and Marine Geoscience Programme Commissioned Report CR/16/032 CR/16/032; Final Last modified: 2016/05/29 11:43 CR/16/032; Final Last modified: 2016/05/29 11:43 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ENERGY AND MARINE GEOSCIENCE PROGRAMME COMMERCIAL REPORT CR/16/032 Devonian and Carboniferous stratigraphical correlation and interpretation in the Orcadian area, Central North Sea, Quadrants 7 - 22 K. Whitbread and T. Kearsey The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights Contributor 2016. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290 EUL. N. Smith Keywords Report; Stratigraphy, Carboniferous, Devonian, Central North Sea. Bibliographical reference WHITBREAD, K AND KEARSEY, T 2016. Devonian and Carboniferous stratigraphical correlation and interpretation in the Orcadian area, Central North Sea, Quadrants 7 - 22. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/16/032. 74pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement -

A Fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic Shift in Earth's Glacial

Tectonophysics 375 (2003) 353–385 www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto A fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic shift in earth’s glacial style? D.A.D. Evans* Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 208109, 210 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA Received 24 May 2002; received in revised form 25 March 2003; accepted 5 June 2003 Abstract It has recently been found that Neoproterozoic glaciogenic sediments were deposited mainly at low paleolatitudes, in marked qualitative contrast to their Pleistocene counterparts. Several competing models vie for explanation of this unusual paleoclimatic record, most notably the high-obliquity hypothesis and varying degrees of the snowball Earth scenario. The present study quantitatively compiles the global distributions of Miocene–Pleistocene glaciogenic deposits and paleomagnetically derived paleolatitudes for Late Devonian–Permian, Ordovician–Silurian, Neoproterozoic, and Paleoproterozoic glaciogenic rocks. Whereas high depositional latitudes dominate all Phanerozoic ice ages, exclusively low paleolatitudes characterize both of the major Precambrian glacial epochs. Transition between these modes occurred within a 100-My interval, precisely coeval with the Neoproterozoic–Cambrian ‘‘explosion’’ of metazoan diversity. Glaciation is much more common since 750 Ma than in the preceding sedimentary record, an observation that cannot be ascribed merely to preservation. These patterns suggest an overall cooling of Earth’s longterm climate, superimposed by developing regulatory feedbacks -

Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse

Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse GEOL 204 The Fossil Record Spring 2020 Section 0103 Fossil Sites of Carboniferous Rainforest April Conway, John Howley, Collapse: Hamilton, USA, Jarrow, UK, Linton, USA, Olivia Medina, and Drew Tidwell Newsham, USA, Nyrany, Czechoslovakia, Joggins, Canada (Joggins, Canada site shown in figure 2) What was the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse? The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse was a minor extinction that happened 305 Ma (Late Moscovian to early Pennsylvanian). It was originally a rainforest home Extinction Patterns on Land to many tetrapods and plants. The rainforest was also very good for the production Plants decreased in diversity which in turn caused a decrease of coal. (Figure 1). in the oxygen levels . This affected the large arthropods and other invertebrates which could not maintain their size with these decreased levels of oxygen. This caused them to be What caused the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse? wiped out during the collapse, especially giant dragonflies. Animals were also drastically affected because of the lack of Originally in the Moscovian the climate was hot and wet which is perfect for the growth of an available resources for survival and were forced to adapt ecosystem in a rainforest. Eventually, the climate changed to cool and dry which caused the living quickly to their new limited surroundings. organisms and plants in the rainforest to struggle. As the plants continued to struggle, the oxygen levels decreased which made life for living organisms even more difficult. Another possible cause of the minor extinction was intense glaciation which led to lower sea levels. This is also related to the issues that arose from a colder climate. -

Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous Chondrichthyans from the Fairfield Group, Canning Basin, Western Australia

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous chondrichthyans from the Fairfield Group, Canning Basin, Western Australia Brett Roelofs, Milo Barham, Arthur J. Mory, and Kate Trinajstic ABSTRACT Teeth from 18 shark taxa are described from Upper Devonian to Lower Carbonif- erous strata of the Lennard Shelf, Canning Basin, Western Australia. Spot samples from shoal facies in the upper Famennian Gumhole Formation and shallow water car- bonate platform facies in the Tournaisian Laurel Formation yielded a chondrichthyan fauna including several known species, in particular Thrinacodus ferox, Cladodus thomasi, Protacrodus aequalis and Deihim mansureae. In addition, protacrodont teeth were recovered that resemble formally described, yet unnamed, teeth from Tournaisian deposits in North Gondwanan terranes. The close faunal relationships previously seen for Late Devonian chondrichthyan taxa in the Canning Basin and the margins of north- ern Gondwana are shown here to continue into the Carboniferous. However, a reduc- tion in species overlap for Tournaisian shallow water microvertebrate faunas between the Canning Basin and South China is evident, which supports previous studies docu- menting a separation of faunal and terrestrial plant communities between these regions by this time. The chondrichthyan fauna described herein is dominated by crushing type teeth similar to the shallow water chondrichthyan biofacies established for the Famennian and suggests some of these biofacies also extended into the Early Carboniferous. Brett Roelofs. Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987 Perth, WA 6845, Australia. [email protected] Milo Barham. Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987 Perth, WA 6845, Australia. [email protected] Arthur J. -

Coevolution of Global Brachiopod Palaeobiogeography and Tectonopalaeogeography During the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4

Li et al. Journal of Palaeogeography (2021) 10:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00095-z Journal of Palaeogeography ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Coevolution of global brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography during the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4 Abstract The global brachiopod palaeobiogeography of the Mississippian is divided into three realms, six regions, and eight provinces, while that of the Pennsylvanian is divided into three realms, six regions, and nine provinces. On this basis, we examined coevolutionary relationships between brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography using a comparative approach spanning the Carboniferous. The appearance of the Boreal Realm in the Mississippian was closely related to movements of the northern plates into middle–high latitudes. From the Mississippian to the Pennsylvanian, the palaeobiogeography of Australia transitioned from the Tethys Realm to the Gondwana Realm, which is related to the southward movement of eastern Gondwana from middle to high southern latitudes. The transition of the Yukon–Pechora area from the Tethys Realm to the Boreal Realm was associated with the northward movement of Laurussia, whose northern margin entered middle–high northern latitudes then. The formation of the six palaeobiogeographic regions of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian brachiopods was directly related to “continental barriers”, which resulted in the geographical isolation of each region. The barriers resulted from the configurations of Siberia, Gondwana, and Laurussia, which supported the Boreal, Tethys, and Gondwana realms, respectively. During the late Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, the Rheic seaway closed and North America (from Laurussia) joined with South America and Africa (from Gondwana), such that the function of “continental barriers” was strengthened and the differentiation of eastern and western regions of the Tethys Realm became more distinct. -

Dinantian Carbonate Development and Related Prospectivity of the Onshore Northern Netherlands

Dinantian carbonate development and related prospectivity of the onshore Northern Netherlands Nynke Hoornveld, 2013 Author: Nynke Hoornveld Supervisors: Bastiaan Jaarsma, EBN Utrecht Prof. Dr. Jan de Jager, VU University Amsterdam Master Thesis: Solid Earth, (450199 and 450149) 39 ECTS. VU University Amsterdam 01-06-2013 Dinantian carbonate development and related prospectivity of the onshore Northern Netherlands Nynke Hoornveld, 2013 Contents Contents……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………..3 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….……4 Geological History of the Netherlands relating to Dinantian development…………………………..……………..7 Tectonic history…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Stratigraphy of the Carboniferous…………………………………………………………………………………………….16 Stratigraphic Nomenclature of the Netherlands……………………………………………………………….………23 Methods……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..26 Seismic interpretation…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…27 Time-depth conversion…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……...35 Well correlation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…38 Carbonate production, precipitation and geometries, with a focus on the Dinantian……….………40 Results………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………..57 Well information, evaluation and reservoir development………………………………………………………..58 Geometry of the Dinantian carbonate build-ups in the Dutch Northern onshore…………..……….75 The geological history -

CO2 As a Primary Driver of Phanerozoic Climate

The role of CO2 in regulating cli- CO as a primary driver of mate over Phanerozoic timescales has 2 recently been questioned using δ18O records of shallow marine carbonate Phanerozoic climate (Veizer et al., 2000) and modeled pat- terns of cosmic ray fluxes (Shaviv and Dana L. Royer, Department of Geosciences and Institutes of the Environment, Veizer, 2003). The low-latitude δ18O Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802, USA, compilation (Veizer et al., 1999, 2000), [email protected] taken to reflect surface water tempera- Robert A. Berner, Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New tures, is decoupled from the CO2 record Haven, Connecticut 06520, USA and instead more closely correlates with the cosmic ray flux data. If correct, Isabel P. Montañez, Department of Geology, University of California, Davis, cosmic rays, ostensibly acting through California 95616, USA variations in cloud albedo, may be Neil J. Tabor, Department of Geological Sciences, Southern Methodist University, more important than CO2 in regulating Dallas, Texas 75275, USA Phanerozoic climate. Here we scrutinize the pre-Quaternary David J. Beerling, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, records of CO , temperature, and cos- Sheffield S10 2TN, UK 2 mic ray flux in an attempt to resolve current discrepancies. We first compare proxy reconstructions and model pre- ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION dictions of CO2 to gauge how securely Recent studies have purported to Atmospheric CO2 is an important we understand the major patterns of show a closer correspondence between greenhouse gas, and because of its short Phanerozoic CO2. Using this record of reconstructed Phanerozoic records of residence time (~4 yr) and numerous CO2 and Ca concentrations in cosmic ray flux and temperature than sources and sinks, it has the potential Phanerozoic seawater, we then modify between CO2 and temperature. -

Characteristics of the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian Boundary and Associated Coal-Bearing Rocks in the Southern Appalachians

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MISSISSIPPIAN-PENNSYLVANIAN BOUNDARY AND ASSOCIATED COAL-BEARING ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS By Kenneth J. England, William H. Gillespie, C. Blaine Cecil, and John F. Windolph, Jr. U.S. Geological Survey and Thomas J. Crawford West Georgia College with contributions by Cortland F. Eble West Virginia Geological Survey Lawrence J. Rheams Alabama Geological Survey and Roger E. Thomas U.S. Geological Survey USQS Open-File Report 85-577 1985 This report la preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or atratlgraphic nomenclature. CONTENTS Page Characteristics of the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian boundary and associated coal-bearing strata in the central Appalachian basin. Kenneth J. Englund and Roger E. Thomas.................................... 1 Upper Mississippian and Lower Pennsylvanian Series in the southern Appalachians. Thomas J. Crawford........................................................ 9 Biostratigraphic significance of compression-impression plant fossils near the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian boundary in the southern Appalachians. William H. Gillespie, Thomas J. Crawford and Lawrence J. Rheams........... 11 Miospores in Pennsylvanian coal beds of the southern Appalachian basin and their stratigraphic implications. Cortland F. Eble, William H. Gillespie, Thomas J. Crawford, and Lawrence J. Rheams...................................................... 19 Geologic controls on sedimentation and peat formation in the Carboniferous of the Appalachian -

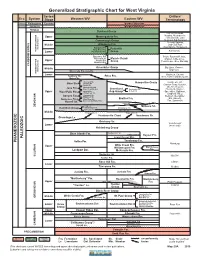

WV Generalized Stratigraphic Column/Chart

Generalized Stratigraphic Chart for West Virginia Series/ Drillers’ Era System Stage Western WV Eastern WV Terminology CENOZOIC Paleogene Eocene Igneous Intrusives MESOZOIC Jurassic Igneous Intrusives PERMIAN Dunkard Group Carroll, Minshall, Murphy, Moundsville, Upper Monongahela Fm. 1st Cow Run, Little Conemaugh Group Dunkard, Big Dunkard Burning Springs, Middle Allegheny Fm. 2nd Cow Run, Kanawha Fm. Gas Sands, Horseneck (Subsystem) New River Fm. Pottsville PENNSYLVANIAN Lower Pocahontas Fm. Group Salt Sands Bluestone Fm. Pride, Ravencliff, Avis, Princeton Ss. Mauch Chunk Maxton, Little Lime, Upper Hinton Fm. Group Pencil Cave, Blue Monday Bluefield Fm. CARBONIFEROUS Greenbrier Group Big Lime, Keener, Middle Big Injun (Subsystem) Maccrady Fm. (south) MISSISSIPPIAN Lower Big Injun, Squaw, Sunbury Sh. Price Fm. Weir, Coffee (Sunbury) Sh. Berea Ss. Cleveland Sh. Gantz, 50’, 30’, Ohio Sh. Chagrin Sh. Hampshire Group Huron Sh. Gordon Stray, Gordon, Hanover Sh. bed 4th, 5th, Bayard, Java Fm. Pipe Creek Sh. bed Greenland Foreknobs Fm. Elizabeth, Warren, Upper West Falls Fm. Angola Sh. Gap Group Scherr Fm. Speechley, Balltown, Rhinestreet Sh. Bradford, Riley, Cashaqua Sh. Sonyea Fm. Middlesex Sh. Benson, Alexander, Elk, Haverty, Genesee Fm./ West River Sh. Brallier Fm. Geneseo Sh./Burket Sh. Fox, Sycamore Harrell Sh. Harrell Sh. DEVONIAN Tully Ls. Millboro Sh. Hamilton Group Mahantango Fm. Mahantango Fm. Marcellus Sh. Marcellus Sh. Middle Tioga ash beds Tioga ash beds Huntersville Chert Needmore Sh. Onondaga Ls. Oriskany Ss. “Corniferous” Lower (west only) Helderberg Group Bass Islands Fm. Big Mountain Sh. Clifton Forge Ss. Keyser Fm. PALEOZOIC Lower Keyser Mbr. PHANEROZOIC Salina Fm. Tonoloway Fm. Newburg Wills Creek Fm. Upper Bloomsburg Williamsport Fm. Fm.