World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 28N FebruaryS – 6 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 28 February – 6 March 2007 Of note this week The IDF imposed a total closure on the West Bank during the Jewish holiday of Purim between 2 – 5 March. The closure prevented Palestinians, including workers, with valid permits, from accessing East Jerusalem and Israel during the four days. It is a year – the start of the 2006 Purim holiday – since Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip have been prevented from accessing jobs in Israel. West Bank: − On 28 February, the IDF re-entered Nablus for one day to continue its largest scale operation for three years, codenamed ‘Hot Winter’. This second phase of the operation again saw a curfew imposed on the Old City, the occupation of schools and homes and house-to-house searches. The IDF also surrounded the three major hospitals in the area and checked all Palestinians entering and leaving. According to the Nablus Municipality 284 shops were damaged during the course of the operation. − Israeli Security Forces were on high alert in and around the Old city of Jerusalem in anticipation of further demonstrations and clashes following Friday Prayers at Al Aqsa mosque. Due to the Jewish holiday of Purim over the weekend, the Israeli authorities declared a blanket closure from Friday 2 March until the morning of Tuesday 6 March and all major roads leading to the Old City were blocked. -

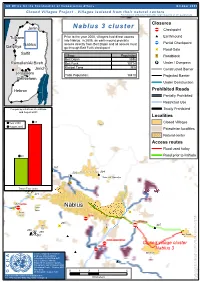

Nablus 3 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) Nablus 3 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm Prior to the year 2000, villagers had direct access Earthmound into Nablus. In 2005, an earthmound prohibits ¬Ç Nablus access directly from Beit Dajan and all access must Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya go through Beit Furik checkpoint D Road Gate Salfit Village Population /" Roadblock Beit Dajan 3696 Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Furik 10714 º¹P Under / Overpass Jericho Khirbet Tana N/A Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 14410 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Under Construction Hebron Prohibited Roads Partially ProhibitedTubas Restricted Use Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited ## and August 2005 Tubas Burqa Localities 45 Closed Villages Year 2000 Yasid August 2005 Beit Imrin Palestinian localities Natural center Nisf Jubeil Access routes Sabastiya Ijnisinya Road used today 290 # 358#20Shave Shomeron Road prior to Intifada ¬Ç An Naqura 287 ## 389 'Asira ash Shamaliya 294 # 293 # ## ## 288¬Ç beit iba 'Asira ash Shamaliya /" Qusin Travel Time (min) 271 D 270Ç SARRA Nablus D ¬ Sarra Sarra Sarra D Sarra ¬Ç At Tur 279 beit furik cp the of part the 265 D ÇÇ 297 Tell ¬¬ delimitation the concerning # Tell # 269 ## ## 296## 268 ## # Beit Dajan 266#267 ## awarta commercial cp ¬Ç Closed village cluster ¬Ç huwwara Nablus 3 ## Closure mapping is a work in Beit Furik progress. Closure data is collected by OCHA field staff and is subject to change. ## Maps will be updated regularly. Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian Information Centre - October 2005 Base data: 03612 O C H A O C H OCHA update August 2005 For comments contact <[email protected]> Tel. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Secretariats of Roads Transportation Report 2015

Road Transportation Report: 2015. Category Transfer Fees Amount Owed To lacal Remained No. Local Authority Spent Amount Clearing Amount classification 50% Authorities 50% amount 1 Albireh Don’t Exist Municipality 1,158,009.14 1,158,009.14 0.00 1,158,009.14 2 Alzaytouneh Don’t Exist Municipality 187,634.51 187,634.51 0.00 187,634.51 3 Altaybeh Don’t Exist Municipality 66,840.07 66,840.07 0.00 66,840.07 4 Almazra'a Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 136,262.16 136,262.16 0.00 136,262.16 5 Banizeid Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 154,092.68 154,092.68 0.00 154,092.68 6 Beitunia Don’t Exist Municipality 599,027.36 599,027.36 0.00 599,027.36 7 Birzeit Don’t Exist Municipality 137,285.22 137,285.22 0.00 137,285.22 8 Tormos'aya Don’t Exist Municipality 113,243.26 113,243.26 0.00 113,243.26 9 Der Dibwan Don’t Exist Municipality 159,207.99 159,207.99 0.00 159,207.99 10 Ramallah Don’t Exist Municipality 832,407.37 832,407.37 0.00 832,407.37 11 Silwad Don’t Exist Municipality 197,183.09 197,183.09 0.00 197,183.09 12 Sinjl Don’t Exist Municipality 158,720.82 158,720.82 0.00 158,720.82 13 Abwein Don’t Exist Municipality 94,535.83 94,535.83 0.00 94,535.83 14 Atara Don’t Exist Municipality 68,813.12 68,813.12 0.00 68,813.12 15 Rawabi Don’t Exist Municipality 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16 Surda - Abu Qash Don’t Exist Municipality 73,806.64 73,806.64 0.00 73,806.64 17 Hay Alkarama Don’t Exist Village Council 7,551.17 7,551.17 0.00 7,551.17 18 Almoghayar Don’t Exist Village Council 71,784.87 71,784.87 0.00 71,784.87 19 Alnabi Saleh Don’t Exist Village Council -

Uprooted Livelihoods

MA’AN Development Center Ramallah Office Al-Nahdah Building / Al-Nahdah St. Al-Masyoun, Ramallah - 5th Floor P.O. Box 51352 or 51793 Jerusalem Phone: +972 2 298-6796 / 298-6698 Fax: +972 2 295-0755 E-mail: [email protected] Gaza Office Gaza City Heidar Abdel Shafi roundabout Moataz (2) building Next to Central Blood Bank Society P.O. Box 5165 Gaza City Phone: +972 8 282-3712 Uprooted Fax: +972 8 282-3712 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.maan-ctr.org MA’AN Livelihoods Development Center Palestinian Villages and Herding Communities in the Jordan Valley Funded by: 2013 Ü Bisan UV90 Bardala Kardala Ein al-Beida Ibziq Givat Sa'alit Al-Farayiyeh UV60 Mechola The Occupied al-Himeh Greater al Maleh Shadmot Mehola Jordan Valley al-Aqaba Rotem Tayasir al-Burg 'Ein al Hilwa-Um al Jmal Hammamat al Maleh (Northern Area) Occupied Palestine Ein al-Hilweh Tubas (West Bank) Maskiot Khirbet Yarza al-Meiteh Khirbet Samra Greater Tammun Mak-hul Khirbet ar Ras al Ahmar Hemdat Al Hadidiya Ro'i Beka'ot Humsa Um al 'Obor UV57 Nablus UV90 Hamra Overview Hamra Jordan Valley Area 1948 Armatice Line Furush Beit Dajan Marj Na’aje Palestinian Communities UV57 Zbeidat Main & Bypass road Argaman Marj Ghazal Regional road Mechora Jk Crossing Points Jiftlik Israeli Settlements Built up area Permeter Cultivated land UV60 Municipal boundries UV57 Massu'a Israeli Administrative Restrictions Damiya (Closed by Israel in 2000) Gittit Interim Agreement Areas Area A Ma'ale Efrayim Jordan Area B Area C Closed Military Areas Ma'ale Efraim UV60 Yafit Israeli Physical Access Restrictions -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

Fourth Phase

___ ____ ______ ______ ______ _______ __________ Palestinian National Authority ______ ______ __________ Higher Commission for Local Elections _______ Fourth Phase Constituency Eligible Government No Constituency Category Population member team voters Jerusalem 1. Arab Al-Jahalin Projects 1240 9 committee Total 1 1240 9 Constituency Eligible Government No Constituency Category Population member team voters Jenin 1. Jenin Municipality 36813 15 2. Misliya Village council 2318 9 3. Anza Village council 2065 9 4. Muthalath Al- Village council 1790 9 Shuhada 5. Dahiyat Sabah Village council 1500 9 Al- Kheir 6. Tura Al- Village council 1142 9 Gharbiya 7. Barta a Village council 3709 9 8. Jalqamus Village council 1922 9 9. Mirka Village council 1601 9 10. Raba Village council 3128 9 11. Al-Attara Village council 1104 9 12. Umm At Tut Projects 1032 9 committee 13. Wadi Birqin Projects 1030 9 Committee Total 13 59154 123 Constituency Eligible Government No Constituency Category Population member team voters Tulkarm 1. Tulkarm Municipality 55975 15 2. Saffarin Village council 1067 9 Total 2 57042 24 1 ___ ____ ______- — ____ ______ _: 2402098_ ____: 2402095 _._: Al-Bireh-Al-Shrafa St. Tel: 2402098 Fax: 2402095 P.O. Box: 3730 ___- ______ _______- ____ _______.____ _: 2825422-08 , ____: - Gaza-AlReemal- AlJanoby- — Madhat whadyAl- St Tel: 08-2825422 Fax: 08-2825655 ___ ____ ______ ______ ______ _______ __________ Palestinian National Authority ______ ______ __________ Higher Commission for Local Elections _______ Constituency Eligible Government No Constituency Category Population member team voters Tubas 1. Wad Al-Far a Village council 2405 9 2. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

Targeted Killings</Em>

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Michigan School of Law Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 39 Issue 2 2018 Targeting the Targeted Killings Case - International Lawmaking in Domestic Contexts Yahli Shereshevsky Hebrew University of Jerusalem Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Yahli Shereshevsky, Targeting the Targeted Killings Case - International Lawmaking in Domestic Contexts, 39 MICH. J. INT'L L. 241 (2018). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol39/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TARGETING THE TARGETED KILLINGS CASE – INTERNATIONAL LAWMAKING IN DOMESTIC CONTEXTS Yahli Shereshevsky* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 242 I. THE DEBATE OVER TARGETED KILLINGS ............... 244 A. Three Main Controversies in the International Law Debate over Targeted Killings ....................... 244 B. Targeted Killings in Israel: From the Targeted Killings Case to the 2014 Gaza Conflict ............. 247 1. The Targeted Killings Case ..................... 247 2. The 2014 Gaza Conflict Report ................. 249 II. THREE COMPLEMENTARY EXPLANATIONS FOR THE ADOPTION OF THE FORMAL MEMBERSHIP APPROACH: JUDICIAL DEFERENCE, THE U.S. LEGAL POSITION AND THE INTERPRETIVE COMMUNITY OF MILITARY LAWYERS, AND A PRESSING NEED ................................ -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n .