"The East and West Are One": the Missouri River Bridge at Mobridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Missouri Valley the Politics of Dam Site Selection and Design

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 1997 Flooding The Missouri Valley The Politics Of Dam Site Selection And Design Robert Kelley Schneiders Texas Tech University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Schneiders, Robert Kelley, "Flooding The Missouri Valley The Politics Of Dam Site Selection And Design" (1997). Great Plains Quarterly. 1954. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1954 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FLOODING THE MISSOURI VALLEY THE POLITICS OF DAM SITE SELECTION AND DESIGN ROBERT KELLEY SCHNEIDERS In December 1944 the United States Con Dakota is 160 feet high and 10,700 feet long. gress passed a Rivers and Harbors Bill that The reservoir behind it stretches 140 miles authorized the construction of the Pick-Sloan north-northwest along the Missouri Valley. plan for Missouri River development. From Oahe Dam, near Pierre, South Dakota, sur 1946 to 1966, the United States Army Corps passes even Fort Randall Dam at 242 feet high of Engineers, with the assistance of private and 9300 feet long.! Oahe's reservoir stretches contractors, implemented much of that plan 250 miles upstream. The completion of Gar in the Missouri River Valley. In that twenty rison Dam in North Dakota, and Oahe, Big year period, five of the world's largest earthen Bend, Fort Randall, and Gavin's Point dams dams were built across the main-stem of the in South Dakota resulted in the innundation Missouri River in North and South Dakota. -

The Late Tertiary History of the Upper Little Missouri River, North Dakota

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 1956 The al te tertiary history of the upper Little iM ssouri River, North Dakota Charles K. Petter Jr. University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Petter, Charles K. Jr., "The al te tertiary history of the upper Little iM ssouri River, North Dakota" (1956). Theses and Dissertations. 231. https://commons.und.edu/theses/231 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LATE TERTIARY H!~TORY OF 'l'HE. UPP.7:B LITTLE MISSOURI RIVER, NORTH DAKOTA A Thesis Submitted to tba Faculty of' the G?"adue.te School of the University ot 1'1ortri Dakota by Charles K. Petter, Jr. II In Partial Fulf'1llment or the Requirements tor the Degree ot Master of Science .rune 1956 "l' I l i This t.:iesis sured. tted by Charles re. Petter, J.r-. 1.n partial lftllment of tb.e requirements '.for the Degree of .Master of gcJenee in tr:i.e ·;rnivarsity of llorth Dakot;a. is .hereby approved by the Committee under. whom l~he work h.a.s 1)EH!Hl done. -- i"", " *'\ ~1" Wf 303937 Illustrations ......... .,............................. iv Oeneral Statement.............................. l Ar..:l:nowlodgments ................................. -

Application Checklist for an Initial Missouri Teacher's

APPLICATION CHECKLIST FOR AN INITIAL MISSOURI TEACHER’S LICENSE FOR MISSOURI GRADUATES Application Form Application for a Missouri Teacher’s Certificate (Initial Professional Certificate) must be completed and signed by the certification officer at the recommending Missouri institution and contain the institution’s official seal. The application must be signed by the applicant; Transcripts Transcripts from ALL institutions attended must be provided. Please be sure your complete social security number is listed. Note: a minimum grade point average of 2.5 on a 4.0 scale in the major field and overall is required; and Background Check A criminal background check must be completed. Please contact L-1 Enrollment Services Division to schedule an appointment by calling 866-522-7067 or online at http://www.l1enrollment.com/. The current processing fee for this procedure is $52.20. Please provide the following information when contacting IBT: • County/District code number of the hiring school district; if not employed please use code number 999999; • Your certification status, which will be a certified educator (E); and • DESE’s ORI number, which is MO920320Z. Any questions regarding this portion of the application process must be directed to the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, Conduct and Investigation Section at 573-522-8315. PLEASE BE SURE THAT THE APPLICATION PACKET IS COMPLETE! An incomplete packet will not be processed. Mail the complete application packet to: Educator Certification Post Office Box 480 Jefferson City, MO 65102-0480 http://dese.mo.gov 573/751-0051 The application and transcripts will be submitted to DESE by the certification officer at the recommending Missouri institution. -

Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis for Kansas City, Missouri

The analysis presented in this report was completed prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States and therefore the forecast estimates do not take into account the economic and housing market impacts of the actions taken to limit contagion of the virus. At this time, the duration and depth of the economic disruption are unclear, as are the extent and effectiveness of countermeasures. HUD will continue to monitor market conditions in the HMA and provide an updated report/addendum in the future. COMPREHENSIVE HOUSING MARKET ANALYSIS Kansas City, Missouri-Kansas U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research As of January 1, 2020 Share on: Kansas City, Missouri-Kansas Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis as of January 1, 2020 Executive Summary 2 Executive Summary Housing Market Area Description The Kansas City Housing Market Area (HMA), coterminous with the Kansas City, MO-KS Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), encompasses 14 counties along the border between Missouri and Kansas. For this analysis, the HMA is divided into two submarkets: (1) the Missouri submarket, which consists of Bates, Caldwell, Cass, Clay, Clinton, Jackson, Lafayette, Platte, and Ray Counties; and (2) the Kansas submarket, which consists of Johnson, Linn, Miami, Leavenworth, and Wyandotte Counties. The city of Kansas City is known for its style of jazz. In 2018, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization designated Kansas City Tools and Resources as a “City of Music,” the only such city in the United States. Find interim updates for this metropolitan area, and select geographies nationally, at PD&R’s Market-at-a-Glance tool. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

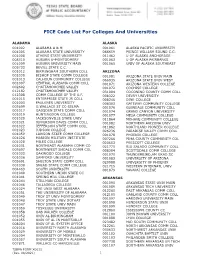

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

North and South Dakota

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BtELIiETIN 575 «v^L'l/"k *. GEOLOGY OP THE NORTH AND SOUTH DAKOTA BY W. R. CALVERT, A. L. BEEKLY, V. H. BARNETT AND M. A. PISHEL WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 1914 vti.'CS i«\ IJ) C -«"PA4 £, * 0 CONTENTS. Introduction.............................................................. 5 Field work............................................................... 6 Previous examinations........:............................................ 6 Geography. .............................................................. 7 Location and extent of area............................................ 7 Relief................................................................ 7 Drainage.............................................................. 8 Culture. ....................................................v .......... 8 Descriptive geology........................................................ 9 Stratigraphy.......................................................... 9 Occurrence of the rocks. ........................................... 9 Cretaceous system (Montana group)................................ 9 Pierre shale.................................................. 9 Character and distribution................................. 9 Age..................................................... 11 Fox Hills^sandstone.......................................... 11 Character and distribution................................. 11 Age...................................................... -

Missouri and Arkansas Region

Atchison Worth Putnam Schuyler Mercer Clark Nodaway Harrison Scotland Sullivan Gentry Adair Knox American Red Cross Holt Grundy Lewis Serving Greater Quad Cities Area Andrew Daviess West Central Illinois DeKalb . Linn Macon (13364) (Moline, IL) Kansas Doniphan Shelby Marion Caldwell Livingston Buchanan Clinton Ralls Atchison Chariton Ray Monroe Platte Carroll Randolph 25150 Pike Calhoun Leavenworth Clay Jackson 25062 Audrain Wyandotte Saline Howard Montgomery Lafayette Boone Lincoln Jersey Callaway Johnson Kansas City Cooper Madison Columbia Warren St. Charles Johnson Pettis St. Lou Cass Gasconade Moniteau St. Miami Louis Cole St. Louis Morgan St. Clair Henry Osage Franklin 25380 Benton Illinois Bates Monroe Miller Jefferson Maries St. Clair Camden Randolph Hickory Crawford Phelps Ste. Vernon Genevieve Pulaski Washington St. Jackson Cedar Perry Dallas Francois Polk Laclede Dent 25R16 Iron Cape Barton Madison Union Dade Webster Girardeau Greene Reynolds Texas 25152 Wright Bollinger Alexander Jasper Shannon Cape Missouri Wayne Lawrence Springfield Scott Girardeau Christian Carter Newton Douglas Stoddard Mississippi Howell Stone Butler New Barry Taney Oregon McDonald Ozark Ripley Madrid Randolph Fulton Benton Carroll Baxter 25060 Clay Boone Marion Rogers Pemiscot Sharp Greene Izard Dunklin Madison Lawrence Washington Newton Searcy Stone Mississippi Independence Craighead 04304 Crawford Van Buren Poinsett Franklin Johnson Cleburne Jackson Pope Arkansas Conway White Cross Logan Crittenden Sebastian Faulkner Woodruff St. Francis Yell Perry -

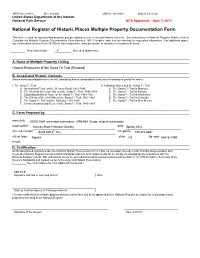

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

Aerial Photography Maps of the Missouri National Recreational River

Aerial Photography Maps of the Missouri National Recreational River Fort Randall Dam. South Dakota to Santee. Nebraska September 2003 Army Corps of Engineers ® Omaha District Table of Contents Welcome Page • A c"Omprch"n,;',., ex~mi"a t ion of the Missouri Ri,,,. addressil1g topics such as " .. ,irs grograph ica\ char~c~ris{iC.'l . .. .th e origin of ill! nickname, "Big Muddy." .. ,irs appearance during Lewis and Clark's "pk jOlln,C')'. 01 Bald Eagle While many bald Threatened and Endangered Species Page • An iliustrMive guide on the arca's rh",aten"d and endallgercd specie,; ourlinil1g" . area d uring the .. ,the need (or the Endan~",,,,d Species Act of 1973. these rapmrs may ."ways of protecting .pecies fOund along the Missouri Ri,,,r. ", the countless reasons and incentives for "",il1g endange",d species. yea r in the 02 ;Iatec\, means tIl e s 'niubthatha,' or Historical Information Page .A historiC"~1 owrvi~'w of the Lewis and Clark Expedition providing specifies on ... .. the ~... "nt:,; that led up to the f~med Expedition . \ ... the conditions as descril>ed in the journals of William Clark . .. the Missouri Ri",r and the Lev,'is & Clark Bicentennial CommemorMion. 04 Ide turtJicrinsrructi;:jns. General and Safety Information Page oat Ramp Coordinates - An ~ ~t ensiw list of ,,',,nernl information and sa(cty pm:autions offering tips on .. Boat Ramp Name Lat .. respecting the' resomce. .. ....... imming. OOating. and ",mping. Spillway 430031 .. reading and na"ig;oting the' Missomi Riwr. 07 ,--" andalLC ,eek 4r 03 Sheet Index Page • An iliustrMi"e map indexing the following sections of the Recreational Ri",r.. -

![Missouri State Archives Finding Aid [998.463]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2939/missouri-state-archives-finding-aid-998-463-1202939.webp)

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid [998.463]

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid [998.463] MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS Kendal Mertens Jefferson City Photograph Collection Abstract: Digital photographs of sites in Jefferson City. Extent: 412 MB (333 images) Physical Description: JPGs Location: Missouri State Archives; Vault ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: None Access Restrictions: None Publication Restrictions: None Preferred Citation: [description of item], [date]; Kendal Mertens Jefferson City Photograph Collection, Record Group 998.463; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Acquisition Information: Gift with Deed; #2017-0055 Processing Information: Processing completed by EW on 03/20/2018. Updated by EW on 03/25/2021. ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION Related Collections MS064 David Denman Photograph Collection MS266 Historic City of Jefferson Collection MS272 Ehrhardt Photograph Collection MS297 Mark Schreiber Photograph Collection MS314 Tom Sater Capital City Collection MS315 Lynn Shaffer Jefferson City Photograph Collection as of 03/25/2021 KENDAL MERTENS JEFFERSON CITY PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, MS463 MS317 Duke Diggs Jefferson City Photograph Collection MS329 Alice Fast Postcard Collection MS340 George Grazier Jefferson City Photograph Collection MS349 Otto Kroeger Photograph Collection MS360 Dr. Arnold G. Parks Jefferson City Postcard Collection MS369 Bob Priddy Collection MS390 Ann Noe Collection MS394 Priesmeyer Shoe Factory Photograph Collection MS399 Bill Fannin Jefferson City Photograph Collection MS400 Gary Kremer Jefferson City Photograph Collection MS402 -

RNL Fundraising Management Case Study: University of Missouri

RUFFALO NOEL LEVITZ | UMKC CASE STUDY University of Missouri-Kansas City Foundation's Investment in RNL Digital Dialogue Results in a 104% increase in Average Gift Size The Perfect Timing In the fall of 2016, Emily Wurtz, director of annual giving at the University of Missouri–Kansas City (UMKC) Foundation, was planning the fiscal year-end campaign when she was invited to the Ruffalo Noel Levitz (RNL) Digital Philanthropy and Millennial Engagement Conference. While attending the conference, Wurtz heard how RNL’s latest product, RNL Digital Dialogue, boosts donor engagement by targeting digital ads in the channels potential supporters use every day—online. Since UMKC was already planning a direct mail campaign, Wurtz knew RNL Digital Dialogue would be a perfect complement to reach donors and increase exposure to the campaign. “Traditionally About UMKC Foundation at UMKC, we’ve been a little conservative in what we’ve tried, and we Founded in 2009, UMKC Foundation is haven’t tested new areas to help with our results,” Wurtz said. “We felt devoted to raising funds for the university this was a perfect opportunity to touch our prospect base in a different and for exercising fiduciary responsibility way than we’ve ever done.” over endowments and other philanthropic investments made to UMKC. Enabling strong, sustained leadership to advance Engaging Donors Digitally the university's interests is the core of The goal of the fiscal year-end campaign was to increase donor reach UMKC Foundation's purpose. and average gift size. Because this was a new venture, the UMKC team wanted to test performance.