Tilburg University Moongazers & Trailblazers Van Gulik, L.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Inquiry of a Coven of Contemporary Witches James Albert Whyte Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1981 An examen of Witches: an ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches James Albert Whyte Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Anthropology Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Whyte, James Albert, "An examen of Witches: an ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches" (1981). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16917. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16917 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An examen of Witches: An ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches by James Albert Whyte A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: Sociology and Anthropology Maj or: Anthropology Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1981 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 WITCHCRAFT 10 WITCHES 23 AN EVENING WITH THE WITCHES 39 COVEN ORGANIZATION 55 STRESS AND TENSION IN THE SWORD COVEN 78 THE WITCHES' DANCE 92 LITERATURE CITED 105 1 INTRODUCTION The witch is a familiar figure in the popular Western imagination. From the wicked queen of Snow White to Star Wars' Yoda, witches and Witch like characters have been used to scare and entertain generations of young and old alike. -

Why Is It Called Easter?

March 20, 2018 Why Is It Called Easter? Easter is the name of the most important Christian holiday, the day we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead after his crucifixion. The resurrection of Jesus resides at the very heart of the gospel: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15:3-4). But, why is this holiday called Easter? Where did the name Easter come from? Let’s shed some light on those questions. Easter is an English word The etymology of the English word Easter indicates that it descends from the Old German—likely from root words for dawn, east, and sunrise. English is a western Germanic language named for the Angles who, along with the Saxons (another Germanic tribe), settled Britain in the 5th century. In fact, the Old German for Easter was Oster (Ostern in the modern). English and German speakers have been using variations of the term Easter for over a millennium. However, most of the countries surrounding Britain and the German principalities of Europe have long used variants of the Latin Pascha (from the Greek for Passover, a transliteration of the Hebrew pesach) as the name of the celebration of Christ’s resurrection. Today, in many non-English speaking countries, Easter is still called by a name derived from the term Pashca. A number of other languages use a term that means Resurrection Feast or Great Day. -

On the Pagan Parallax a Sociocultural Exploration of the Tension Between Eclecticism and Traditionalism As Observed Among Dutch Wiccans 1

Proof version [The pomegranate 12.1 (2010) 49-70] On the Pagan Parallax A Sociocultural Exploration of the Tension between Eclecticism and Traditionalism as observed among Dutch Wiccans 1 Léon A. Van Gulik Abstract Post-modern nature religions face the challenge of justifying their practices and theology since there is no unbroken line between the classic and contemporary Paganisms of the Western world. Against the background of progressing historical knowledge, these religions constantly have to reinvent or recon- struct their traditions. At the same time, the present context is entirely different to that of when the classic Paganisms emerged. By discussing their roots in romanticism and expressivism, both the rele- vancy of the revived nature religions and the challenges they face, are explained. These issues are illus- trated by drawing on initial results of discourse analyses of on-line discussions between Dutch Wic- cans, yielding imaginative narratives of self-justification and self-identification amidst a continuous tension between traditionalism and eclecticism. Generalising these findings to contemporary Paganism at large, I have argued that the latter movement is counterbalancing sociohistorical developments by its changing acts of sanctioning, its aims to remain the maverick, and its constant striving for experien- tial receptivity creating an illusory idea of autonomous movement: the Pagan parallax. The Dutch cabaret artist Theo Maassen once said about dancing: “die eerste stap is altijd lullig” – “that first step is always shitty.”2 That is, the transition from walking to dancing is experienced as awkward. Picture this: one walks onto the dance floor, seemingly unaffected by the music, and then, merely as a function of reaching the desired spot, the bodily posture changes dramatically to facilitate the getting into the groove. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions. -

Many Gods West Presentation List

Many Gods West Presentation List Anaar Niino Feri and The Mighty Dead This is primarily a lore share workshop. We will begin with an exercise designed to vividly recall an ancestor or recently crossed loved one. I will cover Feri lore regarding our ancestors, the Mighty Dead, and their relationship to the Gods. Tools, such as shrines and spirit jars that help us to connect with our ancestors will be also discussed. This workshop will end with an exercise to discover our own legacy. What will we leave behind on our passing? How will we be regarded as ancestors? Please bring paper and pen and feel free to bring a token of your ancestor to share. Anaar is an initiate of the Anderson Feri tradition and has a Masters degree in Arts and Consciousness. She has spent nearly two decades studying the relationship between Feri and its expression through the Arts. Greatly influenced by the mad poesy of Victor Anderson, she seeks to create works of great mystery and power. Anaar is currently the only known grandmaster of the tradition. Anomalous Thracian Religions of Relation: Place, Hospitality, and Regional Cultus in Modern Polytheism An examination of Relational and Regional Dynamics in Polytheist Religion today, including solitary and organized community cultus. Heavy emphasis will be placed on the importance of established (and shifting, transforming) identity, role, and situational knowledge of place in relation to Place. These will be expressed and explored as the requisite dynamics of Hospitality, as applied to religious practice, pursuit, and identity, referencing the ancient ways but drawn forward for the explicit purpose of authentic living today and for a thousand shifting tomorrows. -

Renee: 0:01 This Is Renee Cyr Doing an Interview with Camille on July 11 2019, Discussing Paganism in Lawrence

Renee: 0:01 This is Renee Cyr doing an interview with Camille on July 11 2019, discussing Paganism in Lawrence. How do you define your religion and spiritual path? Camille: 0:19 To define my religion would be, the umbrella term is Paganism. But that means anything that's out of Judaism, or Christianity, or Catholicism. Technically I would be classified as a Wiccan. I'm very nature based, but I also incorporate a specific goddess that I like to make offerings to her. She makes me feel protected and safe. And I think everybody deep down inside, spiritually humans need to believe in something higher than themselves. Not just for accountability of what happens to them in life, but the idea that we're just here alone on this big planet, it's kind of sad. I think people are naturally drawn to religious idols. Mine would be Hekate. Renee: 1:03 How long have you practiced Paganism? Camille: 1:06 Since 2002. I discovered it when I was going to high school. When I was younger, I was forced to go to Catholic school. My family is Romani Gypsy, and Italians on my mom's side. So they're very much about adopting a major religion to kind of help us blend in more. And my grandmother and my mother actually really did take it to heart. It wasn't just like, a chameleon tactic to blend in. Going to Catholic school I realized that it just didn't feel right. Like I would leave church feeling worse than when I went in. -

2006 AEN Conference Special Issue

SPECIAL ISSUE ––– 2006 AEN CONFERENCE VOLUME V ISSUE 1 2010 ISSN: 1833-878X Pages 27-34 Olivia Caputo Water and Stone: The Re-Enactment of the Masculine in the Pagan ‘Reclaiming’ Tradition ABSTRACT This paper seeks to explore models of masculinity present within the contemporary spiritual community of the Reclaiming Collective in San Francisco, United States of America. The Reclaiming Collective is part of the wider contemporary Goddess spirituality movement, a movement which promotes the importance of changing patriarchal images of the divine through focus on the Goddess. Through an analysis of both the writings of Starhawk, the most read and published member of the collective, and the discussions and articles with the collective's long-running journal Reclaiming Quarterly this paper reveals the conflict between patriarchal and more radical models of masculinity. It concludes that the fluidity of gender promoted within the Reclaiming Collective stimulates members to understand masculinity as positive, anti-sexist and multifaceted. BIOGRAPHY Olivia Caputo is a PhD candidate at The University of Queensland's School of History Philosophy Religion and Classics. Her research involves critique of gender theory in the writing of two pioneers of the feminist Goddess movement, Carol P. Christ and Starhawk. Olivia has travelled to both the U. S. and the U. K. to gather material about contemporary Goddess communities such as the Reclaiming Collective in San Francisco and the Priestesses of Avalon in Glastonbury. She has presented papers at the Alternative 27 Expressions of the Numinous conference in 2006 and at the Association for Research on Mothering conference in 2007. Her other research interests include community radio, sustainable agriculture and the alternative D. -

Eostre in Britain and Around the World

I was delighted to recent- Eostre in Britain and ly discover that many of Around the World the Iranians who escaped from Khomeni’s funda- mentalist Islamic rule of 01991, Tana Culain ‘K’A’M terror into exile - and no doubt many still trapped - are actually quite Pa- I t is no coincidence that and the Old German Eos- gan in their beliefs. A the Spring Equinox, tre, Goddess of the East. friend of mine was kind Passover, and Easter all Eostre was originally the enough to explain to me fall at the same time of name of the prehistoric that March 21 remains year. west Germanic Pagan Noruz, the ancient Per- spring festival, which is sian New Year. Many Per- The Christian Easter is a not to say that this same sians grow new seeds at lunar holiday and always festival was not celebrated this time of year and each falls on the first Sunday world over by many other family member must after the first full moon af- names. jump over seven fires ter the Spring Equinox. If made of thorns and bush- the full moon is on a Sun- es in a purification ritual. day, Easter is the next Special treats of seven Sunday. Why don’t the dried fruits and nuts are powers that be allow East- given out, and eggs are er to occur on a full moon colored and put on a fam- Sunday? Probably the ily altar alongside a mir- Christian Easter is too ror, coins, sprouted masculine a day, being grains, water, salt, and tu- the resurrection of a mon- lips. -

1 March 2021 Diversity/Cultural Events

MARCH 2021 DIVERSITY/CULTURAL EVENTS & CELEBRATIONS Women’s History Month National Women’s History Month began as a single week and as a local event. In 1978, Sonoma County, California, sponsored a women’s history week to promote the teaching of women’s history. The week of March 8 was selected to include “International Women’s Day.” This day is rooted in such ideas and events as a woman’s right to vote and a woman’s right to work, women’s strikes for bread, women’s strikes for peace at the end of World War I, and the U.N. Charter declaration of gender equality at the end of World War II. This day is an occasion to review how far women have come in their struggle for equality, peace and development. In 1981, Congress passed a resolution making the week a national celebration, and in 1987 expanded it to the full month of March. The 2021 theme is Valiant Women of the Vote: Refusing to be Silenced continues to celebrate the Suffrage Centennial” celebrates the women who have fought for woman’s right to vote in the United States. For more information visit http://www.nwhp.org/. Irish American Heritage Month A month to honor the contributions of over 44 million Americans who trace their roots to Ireland. Celebrations include celebrating St. Patrick’s Day (March 17th) with parades, family gathering, masses, dances, etc. Due to COVID-19, many of these events have been cancelled. For more information visit the Irish-American Heritage Month website at http://irish-american.org/. -

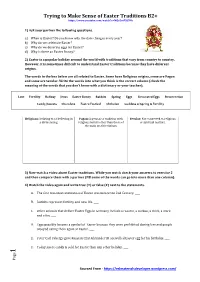

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQz2mF3jDMc 1) Ask your partner the following questions. a) When is Easter? Do you know why the date changes every year? b) Why do we celebrate Easter? c) Why do we decorate eggs for Easter? d) Why is there an Easter Bunny? 2) Easter is a popular holiday around the world with traditions that vary from country to country. However, it is sometimes difficult to understand Easter traditions because they have different origins. The words in the box below are all related to Easter. Some have Religious origins, some are Pagan and some are Secular. Write the words into what you think is the correct column (check the meaning of the words that you don’t know with a dictionary or your teacher). Lent Fertility Holiday Jesus Easter Bunny Rabbits Spring Eggs Decorated Eggs Resurrection Candy/Sweets Chocolate Eostre Festival Christian Goddess of Spring & Fertility Religious: Relating to or believing in Pagan: A person or tradition with Secular: Not connected to religious a divine being. religious beliefs other than those of or spiritual matters. the main world religions. 3) Now watch a video about Easter traditions. While you watch check your answers to exercise 2 and then compare them with a partner (NB some of the words can go into more than one column). 4) Watch the video again and write true (T) or false (F) next to the statements. A. The first recorded celebration of Easter was before the 2nd Century. ____ B. Rabbits represent fertility and new life. -

Ostara - the Spring Equinox 2009

The Controversial Cauldron Ostara - The Spring Equinox 2009 Inside this issue: Ostara ~ Pg ~ 2 Gods of the Season ~ Pg ~ 4 Ostara Ritual ~ Pg ~ 5 Animal Wisdom ~ Pg ~ 6 Crafter’s Corner ~ Pg ~ 8 Legacy ~ Pg ~ 9 Pagan Symbolism ~ Pg ~ 10 On the Rocks ~ Pg ~ 11 The Alder Tree ~ Pg ~ 13 Container Garden ~ Pg ~ 15 Pagan Kitchen ~ Pg ~ 18 Herb Garden ~ Pg ~ 25 Ostara Altars ~ Pg ~ 27 Divination Depot ~ Pg ~ 28 Artist’s Loft ~ Pg ~ 29 Festival of Nowruz ~ Pg ~ 30 Bard’s Corner ~ Pg ~ 32 Australia ~ Pg ~ 33 Edition 2:2 Sponsored by A Young Hare by Albrecht Durer (1502) Controverscial.com Group Information: Welcome to the Email Witches Newsletter • Members: 711 • Founded: Jul 17, 2002 • Language: English Email Witches is a pagan friendly email group attracting people • Representing: from all walks of life, from all spectrums of society and from all around the world. Most are individuals seeking a personal Argentina, Australia, practical religion that can be adapted to their own needs and Bulgaria, Canada, Costa criteria, and Wicca is a wonderfully diverse religion that meets Rica, England, France, these needs. Email Witches, a Yahoo! Group, is set up as a place Greenland, Hawaii, where those of same interest can meet, discuss, share and gain Hungary, India, Jamaica, more information about their chosen paths. All visitors to my Italy, Kuwait, Mexico, website Controverscial.com are welcome, so feel free to join us New Zealand, The and make new friends. Netherlands, Nigeria, Nova Scotia, Panama, the Best Wishes Philippines, Peru, South http://www.controverscial.com/ Africa, Scotland, Slovenia, http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Email_Witches/ the USA and Wales . -

The Methodology of Resistance in Contemporary Neopaganism

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2012 The ethoM dology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPaganism Rebecca Short [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Short, Rebecca, "The eM thodology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPaganism" (2012). Summer Research. Paper 151. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rebecca Short 24 September 2012 Professor Greta Austin The Methodology of Resistance in Contemporary NeoPagan Culture The number of adherents of NeoPaganism is one of the fastest growing, doubling in numbers about every eighteen months. 1 NeoPaganism is a set of several religious traditions and spiritualities that seek to either (1) painstakingly reconstruct the indigenous religions of the Christianized world, especially those of Europe, or (2) reinterpret these religions in the contemporary era to formulate new religious traditions. Reconstructionist NeoPagan traditions include Asatru , a Norse Reconstructionist path, and Hellenismos , a Greek Reconstructionist religion. More contemporary, eclectic, new religious movements include Wicca, a tradition of religious witchcraft born out of the ancient Hermetic school of spirituality and magic practice. Wicca is by far the most popular tradition (or, now, set of traditions) in all of NeoPaganism. This religious tradition was started by a man named Gerald Gardner in 1950s England.