The United States and Japan in Global Context: 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncorrected Transcript

1 JAPAN-2013/05/03 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION GROWTH, ENERGY AND ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP: JAPAN'S CURRENT OBSTACLES AND NEW OPPORTUNITIES Washington, D.C. Friday, May 3, 2013 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction: RICHARD BUSH, Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Moderator: MIREYA SOLIS Senior Fellow and Philip Knight Chair in Japan Studies The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: TOSHIMITSU MOTEGI Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Government of Japan * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 JAPAN-2013/05/03 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: Welcome to Brookings on a beautiful Friday afternoon. It's my great pleasure to welcome you to this afternoon's event. My name is Richard Bush. I'm the Director of the Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies here at Brookings. We're very privileged this afternoon to hear an address by His Excellency, Toshimitsu Motegi, who is the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry in the Government of Japan. He will speak on economic growth, energy and economic partnership, Japan's current obstacles and new opportunities. After the Minister speaks my colleague, Dr. Mireya Solis, will moderate the discussions and we need to end promptly at 3:50. I think there's biographical information about Minister Motegi outside. I will just say that he is a graduate of Tokyo University in 1978. He received a Masters from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He is now in his seventh term as a member of Japan's lower house. -

2013-JCIE-Annual-Report.Pdf

Table of Contents 2011–2013 in Retrospect .................................................................................................................................3 Remembering Tadashi Yamamoto ............................................................................................................6 JCIE Activities: April 2011–March 2013 ........................................................................................................9 Global ThinkNet 13 Policy Studies and Dialogue .................................................................................................................... 14 Strengthening Nongovernmental Contributions to Regional Security Cooperation The Vacuum of Political Leadership in Japan and Its Future Trajectory ASEAN-Japan Strategic Partnership and Regional Community Building An Enhanced Agenda for US-Japan Partnership East Asia Insights Forums for Policy Discussion ........................................................................................................................ 19 Trilateral Commission UK-Japan 21st Century Group Japanese-German Forum Korea-Japan Forum Preparing Future Leaders .............................................................................................................................. 23 Azabu Tanaka Juku Seminar Series for Emerging Leaders Facilitation for the Jefferson Fellowship Program Political Exchange Programs 25 US-Japan Parliamentary Exchange Program ......................................................................................26 -

Volume II, Issue 3 | March 2021

Volume II, Issue 3 | March 2021 DPG INDO-PACIFIC MONITOR Volume II, Issue 3 March 2021 ABOUT US Founded in 1994, the Delhi Policy Group (DPG) is among India’s oldest think tanks with its primary focus on strategic and international issues of critical national interest. DPG is a non-partisan institution and is independently funded by a non-profit Trust. Over past decades, DPG has established itself in both domestic and international circles and is widely recognised today among the top security think tanks of India and of Asia’s major powers. Since 2016, in keeping with India’s increasing global profile, DPG has expanded its focus areas to include India’s regional and global role and its policies in the Indo-Pacific. In a realist environment, DPG remains mindful of the need to align India’s ambitions with matching strategies and capabilities, from diplomatic initiatives to security policy and military modernisation. At a time of disruptive change in the global order, DPG aims to deliver research based, relevant, reliable and realist policy perspectives to an actively engaged public, both at home and abroad. DPG is deeply committed to the growth of India’s national power and purpose, the security and prosperity of the people of India and India’s contributions to the global public good. We remain firmly anchored within these foundational principles which have defined DPG since its inception. DPG INDO-PACIFIC MONITOR This publication is a monthly analytical survey of developments and policy trends that impact India’s interests and define its challenges across the extended Indo-Pacific maritime space, which has become the primary theatre of global geopolitical contestation. -

Tokyo Jungle Convergence Between the Historical Reality of Anti-Nuclear Discourse and the Increasing Self-Reflexivity of a Maturing Narrative Form

Introducing Japanese Popular Culture Edited by Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade 1 Routledge 1~ Taylor&. Francls Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 selection and editorial matter, Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade; individual chapters, the contributors The right of Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or To our students reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN: 978-1-138-85208-2 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-85210-5 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-72376-1 (ebk) Typeset in Bembo by codeMantra Visit the companion website: www.routledge.com/cw/Freedman Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders for their permission to reprint material in this book. -

Sony Playstation 3

Sony PlayStation 3 Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments .hack: Sekai no Mukou ni + Versus - Hybrid Pack Bandai Namco Games 007: Quantum of Solace Activision Agarest Senki Cyber Front Aquanaut's Holiday: Kakusareta Kiroku Sony Computer Entertainment... Armored Core 4 From Software Army of Two EA Games Army of Two: Special Edition EA Games Assassin's Creed III Ubisoft Attouteki Yuugi: Mugen Souls Cyber Front Batman: Arkham Asylum Eidos Interactive Battlefield 3 Electronic Arts Battlefield: Bad Company EA Beowulf Ubisoft Biohazard: Revival Selection Capcom Bionic Commando Capcom Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War Koei Blazing Angels: Squadrons of WWII Ubisoft Borderlands 2 2K Games Call of Duty 3 Activision Call of Duty: Black Ops II Activision Catherine Atlus Club, The Sega Cursed Crusade, The CyberFront Dai-2-Ji Super Robot Taisen OG Bandai Namco Games Dante's Inferno: Death Edition Electronic Arts Dark Souls Bandai Dark Souls: Prepare to Die Edition Bandai Dead Island Deep Silver Dead Island: Game of the Year Edition Deep Silver Dead Space EA Def Jam: Icon EA Games Demon's Souls Sony Computer Entertainment Devil May Cry HD Collection Capcom Dishonored Bethesda Softworks Dragon Ball Z: Budokai HD Collection Namco Bandai Games E.X. Troopers Capcom F.E.A.R. 2: Project Origin Warner Bros. Interactive Fallout 3: English Version Bethesda FIFA 13 Electronic Arts Fight Night Round 3 EA Sports FolksSoul SCEI FolksSoul: BigHit Series SCEI Front Mission Evolved Square Enix Genji: Days of the Blade SCE Korea Grand -

Avm 40 | 50 Operatingmanual

AVM 40 | 50 OPERATING MANUAL UPDATES: www.anthemAV.com SOFTWARE VERSION 1.3x ™ SAFETY PRECAUTIONS READ THIS SECTION CAREFULLY BEFORE PROCEEDING! WARNING RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK DO NOT OPEN WARNING: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. The lightning flash with arrowpoint within an equilateral triangle warns of the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product’s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle warns users of the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the appliance. WARNING: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FIRE OR ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS PRODUCT TO RAIN OR MOISTURE AND OBJECTS FILLED WITH LIQUIDS, SUCH AS VASES, SHOULD NOT BE PLACED ON THIS PRODUCT. CAUTION: TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK, MATCH WIDE BLADE OF PLUG TO WIDE SLOT, FULLY INSERT. CAUTION: FOR CONTINUED PROTECTION AGAINST RISK OF FIRE, REPLACE THE FUSE ONLY WITH THE SAME AMPERAGE AND VOLTAGE TYPE. REFER REPLACEMENT TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. WARNING: UNIT MAY BECOME HOT. ALWAYS PROVIDE ADEQUATE VENTILATION TO ALLOW FOR COOLING. DO NOT PLACE NEAR A HEAT SOURCE, OR IN SPACES THAT CAN RESTRICT VENTILATION. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS 1. Read Instructions – All the safety and operating instructions should be read before the product is operated. 2. Retain Instructions – The safety and operating instructions should be retained for future reference. 3. Heed Warnings – All warnings on the product and in the operating instructions should be adhered to. -

Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N MICHAEL J. MAZARR, JOE CHERAVITCH, JEFFREY W. HORNUNG, STEPHANIE PEZARD What Deters and Why Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3142 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0397-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: REUTERS/Kyodo Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled What Deters and Why: North Korea and Russia, sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

For Whom Japan's Last Dance Is Saved—China, the United States

Cambridge Gazette: Politico-Economic Commentaries No. 4 (March 29, 2010) Jun Kurihara and James L. Schoff1 For Whom Japan’s Last Dance Is Saved—China, the United States, or Chimerica?2 1. Japan-U.S. Security Treaty at 50 The year 2010 celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty.3 Although the importance of geopolitics itself has hardly changed since 1960, East Asia’s geopolitics has changed drastically. The Japan-U.S. alliance was established as East Asia’s bulwark against communism during the Cold War era. But China’s rise and other developments highlight a transformed environment. As partners, Japan and the United States have been loyal for decades and largely successful but the regional dance floor is more crowded than before, the music has changed, and the fashion is new. This essay explores competing perspectives for the Japan-U.S. alliance amidst these changing politico-economic circumstances. Against this backdrop, the authors ask ourselves for whom Japan’s last dance is saved. Do policy makers in Tokyo believe that a choice between China and the United States might become necessary in the future? Should Japan seek a less exclusive relationship with the United States, and what are the key factors that will influence this decision? China’s rise is inevitable, undeniable, and unstoppable. Especially since the so-called Lehman Shock that rocked global financial markets in 2008, China has demonstrated a resilient economic performance, and its economic growth makes the U.S. and Japanese recovery look extremely lackluster.4 Last year China became the world’s largest exporter by surpassing Germany, and this year China’s GDP is expected to overtake Japan’s. -

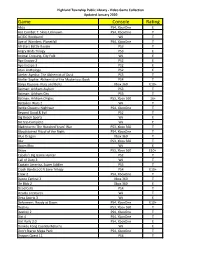

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Mizuho Economic Outlook & Analysis

Mizuho Economic Outlook & Analysis Policy Issues facing the Abe Administration in the final stage of Abenomics - Looking beyond to “post-Abenomics” - October 10, 2018 Copyright Mizuho Research Institute Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Contents 1. Policy Issues of the Abe Administration [ Overview ] P 3 2. Key Policy Issues of the Abe Administration [ Details ] P 4 3. Future Points of Focus P 12 4. Shift in Priorities of Abenomics P 13 Conclusion P 14 1 Summary The Liberal Democratic Party leadership election held in September 2018 saw LDP President (Prime Minister) Shinzo Abe capture his third consecutive victory and party leadership for the next three years. During his last three-year term under the LDP constitution, the Abe administration needs to complete the final stage of Abenomics and draw up a roadmap for the post-Abenomics era. Over the past nearly six years, the Abe administration has promoted its economic policy featuring “three arrows” and “three new arrows,” and the policy has demonstrated certain achievements, for example, substantial progress made in overcoming deflation. But Japan’s full-fledged economic recovery is only halfway down the road. In the coming years, the government needs to advance its policy agenda below and address important medium- and long-term issues. This report examines (1) consumption tax increase, (2) fiscal consolidation, (3) monetary policy, (4) growth strategy, (5) social security, (6) employment, and (7) regional revitalization as the government’s key policy issues. Japan is facing numerous domestic and foreign affairs challenges, including changing the current Japanese era name, the Upper House election, chairing the G20 summit in 2019, and hosting the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

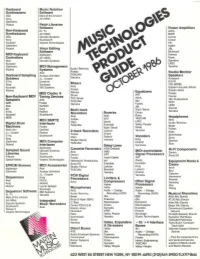

B~F";, Roland Patch Librarian Software Power Amplifiers Non-Keyboard Dr

Keyboard Music Notation Synthesizers Software Akai Mark 01 the Unicorn Korg Jim Miller Oberheim B~f";, Roland Patch Librarian Software Power Amplifiers Non-Keyboard Dr. Ts Ashly Synthesizers Jim Miller C ~O BGW Akai Opcode Systems Carver Korg Southworth Crown Kurzweil Voyelra Technologies HH Oberheim Haller Roland Voice Editing JBL Software Mcintosh MIDI Keyboard digidesign Ramsa Controllers Jim Miller Rane ~OoQ~ Symetrix Akai Opcode Systems Kurzwell UREI Oberheim MIDI Management Yamaha Roland Systems AudiO-Technlca Akai Fostex Studio Monitor Keyboard Sampling Axxess Unlimited TASCAM Speakers Systems J.L. Cooper Yamaha Auratone E-mu Drawmer B&W Korg Sycologic Mixers CSI (M DM) Kurzweil 360 Systems Akai Eastern Acoustic Works Roland Fostex Electro-Voice Ramsa Fostex MIDI Clocks & ART Shure Fourier Non-Keyboard MIDI Timing Devices Ashly TAC/Amek JBL Professional Samplers AXE dbx TASCAM ROR AMS Fostex Fostex Yamaha UREI Akai Gartield JBL Visonik bel Korg Klark-Teknik Multi-track Yamaha E-mu Roland Recorders Reverbs Orban Kurzweil Southworth Akai AKG Rane Headphones MDB TASCAM Fostex ART AKG MIDI /SMPTE UREI Otari Alesis Audio-Technica Digital Drum Interfaces Valley People TASCAM Eventide Beyer Machines Fostex White Klark-Teknik Fostex Akai-Linn Garfield 2-track Recorders Lexicon Yamaha J.L. Cooper Roland Koss Fostex Orban E-mu Southworth Sennheiser Olari Roland Vocoders Sony Korg Korg Studer/ Revox Yamaha Stanton Oberheim MIDI /Computer Roland TASCAM Stax Roland Interfaces Delay Lines Syntovox digidesign ADSlDeltalab Sampled Sound Cassette Recorders Hi-Fi Components Opcode Systems Akai AMS MIDI-controllable Libraries Roland Denon Denon ART Signal Processors Sony ES K-Muse Southworth Fostex Audio Digital ART Optical Media Voyetra Technologies Nakamichi Professional bel Alesis Equipment Racks & Sony ES Eventide Eventide Cases EPROM Burners MIDI Accessories Lexicon Korg Studer/ Revox Anvil digidesign Akai Lexicon TASCAM Marshall Bud Oberheim Axxess Unlimited Roland Yamaha Calzone J.L.